Keratoconus

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Keratoconus is an uncommon corneal disorder where the central or paracentral cornea undergoes progressive thinning and steepening, causing irregular astigmatism.

Disease Entity

Keratoconus adult eye (ICD-9 #371.60).

Disease

German professor Burchard Mauchart was the first physician to describe keratoconus, in 1748; he referred to it as staphyloma diaphanum. In 1854, John Nottingham, a British physician, named it conical cornea. John Horner, a Swiss physician, in 1869 was the first to give the term keratoconus to the disease.[1]

Keratoconus is the most common corneal ectatic disorder where the central or paracentral cornea undergoes progressive thinning and steepening, causing high irregular astigmatism and poor quality of vision. It was thought to be rare, but more awareness among ophthalmologists about the disease led to an increase in diagnosis and prevalence, which varies between regions. It is considerably higher in the Middle East,[2] [3][4] India,[5] China,[6] and Australia.[7]

Etiology

The etiology is unknown, but several factors leading to progression have been described. Inheritance and environmental factors are suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of ectatic corneal diseases, with 8% resulting from genetic mutations and 92% from environmental factors.[8][9][10] The hereditary pattern is neither prominent nor predictable, but positive family histories have been reported. The prevalence of keratoconus is often reported to be 1 in 700.[11]

Keratoconus is associated with atopy and eye rubbing. Eye rubbing and repeated trauma in genetically predisposed individuals results in keratoconus and its progression.[12][13][14] Systemic disorders such as Down syndrome, Leber congenital amaurosis, and Ehlers-Danlos/connective disorders are also associated with keratoconus.

Risk Factors

- Eye rubbing, associated with atopy or vernal keratoconjunctivitis

- Sleep apnea

- Connective tissue disorders

- Floppy eyelid syndrome[15]

- Retinitis pigmentosa

- Positive family history

- Down syndrome

- Hormonal changes in pregnancy[16]

- Selective tissue estrogenic activity regulator (STEAR) therapy[17]

- Hypothyroidism[18]

General Pathology

Keratoconus can show the following pathologic findings: fragmentation of Bowman layer, thinning of stroma and overlying epithelium, folds or breaks in Descemet membrane, and variable amounts of diffuse corneal scarring.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology's Pathology Atlas contains a virtual microscopy image of keratoconus.

Pathophysiology

Histopathology studies demonstrated breaks in or complete absence of Bowman layer, collagen disorganization, scarring, and thinning. The etiology of these changes is unknown, though some suspect changes in enzymes that lead to the breakdown of collagen in the cornea. While a genetic predisposition to keratoconus is suggested, a specific gene has not been identified. Although keratoconus does not fulfill the criteria for inflammatory disease, studies show a significant role of proteolytic enzymes, cytokines, and free radicals (matrix metalloproteinase 9 [MMP-9], interleukin 6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) even in subclinical disease, showing a quasi-inflammatory characteristic in keratoconus.[19]

Primary Prevention

No preventive strategy has been proven effective to date. Some feel that eye rubbing or pressure (eg, sleeping with the hand against the eye) can cause and/or lead to the progression of keratoconus. Patients should be informed not to rub their eyes. In some patients, avoidance of allergens and treatment of ocular surface disease may help decrease eye irritation and therefore decrease eye rubbing.

Diagnosis

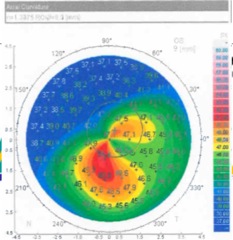

Diagnosis can be made by slit-lamp examination and observation of central or inferior corneal thinning. Computerized videokeratography is useful in detecting early keratoconus and allows following of its progression. Ultrasound pachymetry can also be used to measure the thinnest zone on the cornea. New algorithms using computerized videokeratography have been devised which now allow the detection of forme fruste, subclinical, or suspected keratoconus. These devices may allow better screening of patients for prospective refractive surgery.

History

The majority of cases of keratoconus are bilateral, but often asymmetric. The less-affected eye may show a high amount of astigmatism or mild steepening. Onset is typically in early adolescence and progresses into the mid-20s and 30s. However, cases may begin much earlier or later in life, and progression may also persist beyond the 30s.[20] There is a variable progression for each individual. There is often a history of frequent changes in eyeglass prescription that do not adequately correct vision. Another common progression is from soft contact lenses to toric or astigmatism-correcting contact lenses, to rigid gas-permeable contact lenses. A complete ocular and medical history should be taken, including change in eyeglass prescription, decreased vision, history of eye rubbing, medical problems, allergies, and sleep patterns.

Physical Examination

A thorough and complete eye exam should be performed on any patient suspected of having keratoconus.

The general health of the eye should be assessed, and appropriate ancillary tests should be done to assess corneal curvature, astigmatism, and thickness. The best potential vision should also be evaluated. Many of the potential exam components are listed below:

- Measurement of uncorrected visual acuity

- Measurement of visual acuity with current correction (the power of the present correction recorded) at distance and when appropriate at near

- Measurement of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) with spectacles and hard or gas-permeable contact lenses (with refraction when indicated)

- Measurement of pinhole visual acuity

- Retinoscopy to check for scissoring reflex

- Slit-lamp biomicroscopy of the anterior segment including lid tightness and papillae in upper tarsal conjunctiva

- Keratometry, computerized topography, computerized tomography, or ultrasound pachymetry

Signs

Early signs of keratoconus include the following:

- Asymmetric refractive error with high or progressive astigmatism

- Keratometry showing high astigmatism and irregularity (the axis that does not add to 180 degrees)

- Scissoring of the red reflex on retinoscopy

- Inferior steepening, skewed axis, or elevated keratometry values on K reading and computerized corneal topography

- Corneal thinning, especially in the inferior cornea; maximum corneal thinning corresponds to the site of maximum steepening or prominence

- Rizzuti sign, a conical reflection on the nasal cornea when a penlight is shone from the temporal side

- Fleischer ring, an iron deposit often present within the epithelium around the base of the cone; brown in color and best visualized with a cobalt blue filter

- Vogt striae, which are fine, roughly vertical parallel striations in the stroma; they generally disappear with firm pressure applied over the eyeball and reappear when pressure is discontinued

Later signs of keratoconus include the following:

- Munson sign, a protrusion of the lower eyelid in downgaze

- Breaks in Bowman membrane

- Acute hydrops, a condition where a break in Descemet membrane allows aqueous to enter into the stroma causing severe corneal thickening, decreased vision, light sensitivity, tearing, and pain

- Stromal scarring after the resolution of acute hydrops, which paradoxically may improve vision in some cases by changing corneal curvature and reducing irregular astigmatism

Symptoms

Symptoms include progressive changes in vision not easily corrected with eyeglasses.

Clinical Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made based on the history of changing refraction, poor best spectacle-corrected vision, scissoring reflex on retinoscopy, and abnormalities in keratometry, corneal topography, and corneal tomography, in association with corneal thinning and inferior steepening; characteristic slit-lamp findings can often be seen.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnostic procedures include the following:

- Slit-lamp examination

- Retinoscopy (assessment of scissor reflex)

- Hard or gas-permeable contact lens trial, as improved vision with lenses eliminates other sources of poor vision, including amblyopia

- Measurement of K values

- Ultrasound pachymetry

- Computerized corneal topography

- Tear film biomarkers, like IL-6, TNF-α, and MMP-9, which were overexpressed in tears of keratoconus patients, indicating pathogenesis of keratoconus might involve chronic inflammatory events[21][22][23]

- Computerized corneal tomography (rotating Scheimpflug, rotating slit-beam photography)

Differential Diagnosis

- Pellucid marginal degeneration

- Keratoglobus

- Contact lens–induced corneal warpage

- Corneal ectasia post–refractive laser treatment

Management

General Treatment

The goals of treatment are to provide functional visual acuity and to halt changes in the corneal shape if progressing.

For visual improvement and astigmatism management, spectacles or soft toric contact lenses can be used in mild cases. Rigid gas-permeable contact lenses are needed in the majority of cases to neutralize the irregular corneal astigmatism. The majority of patients who can wear hard or gas-permeable contact lenses have a dramatic improvement in their vision. Specialty contact lenses have been developed to better fit the irregular and steep corneas found in keratoconus; these include (but are not limited to) Rose K, custom-designed contact lenses (based on topography and/or wavefront measurements), semi–scleral contact lenses, piggyback lens use (hard lens over soft lens), scleral lenses, hybrid lenses, and PROSE (prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem). Patients who become contact lens intolerant or do not have acceptable vision, typically from central scarring, can proceed to surgical alternatives.

The primary treatment for progressive keratoconus, or keratoconus in young patients likely to progress at some point, is corneal collagen crosslinking. A drug and device combination product (Photrexa Viscous, Photrexa and the KXL System) for epithelium-off corneal collagen crosslinking was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the spring of 2016. Conventional corneal crosslinking was made available under CE mark throughout Europe 10 years earlier. Corneal collagen crosslinking is a minimally invasive treatment using riboflavin and UV light to induce stiffening of the corneal stroma through the formation of additional crosslink bonds within the extracellular matrix of the stromal collagen. In the conventional procedure, the corneal epithelium is debrided using standard clinical techniques, followed by soaking of the cornea with drops of ophthalmic riboflavin 5-phosphate solution. The riboflavin sensitizer is then activated with exposure of the cornea to UV light for a period of 30 minutes. Variations of this conventional "epithelium-off" technique involve higher intensities of UV for shorter time periods (accelerated crosslinking) or nonremoval of the epithelium ("epithelium-on") techniques. The pivotal FDA trials and most European datasets demonstrate a high success rate for the conventional epithelium-off crosslinking approach. Other approaches have shown some promise and success but overall have been less consistent and reliable in their abilities to halt keratoconus.[24]

Medical Therapy

Patients with associated medical conditions should have these attended to properly. Atopic or vernal conjunctivitis should be treated using topical antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, or anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory treatments such as topical steroids, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or lifitegrast.

Since the incidence of sleep apnea is very high in keratoconus, and because this condition may contribute to the pathogenesis of keratoconus and other medical conditions, all keratoconus patients should be questioned regarding sleep habits. Sleep studies and CPAP mask wear, if found necessary, are recommended for at-risk patients.

Medical therapy for patients who have an episode of corneal hydrops involves acute management of the pain and swelling. Patients are usually given a cycloplegic agent and sodium chloride (Muro) 5% ointment and may be offered a pressure patch. After the pressure patch is removed, patients may still need to continue sodium chloride drops or ointment for several weeks to months until the episode of hydrops has resolved. Patients are advised to avoid vigorous eye rubbing or trauma.

Medical Follow-up

Since the availability of corneal collagen crosslinking, patients are usually followed on a 3- to 6-month basis to monitor the progression of the corneal thinning and steepening and the resultant visual changes. This allows the physician to determine if crosslinking treatment is indicated. Crosslinking is indicated at the onset of documented progression of keratoconus to improve prognosis and preserve visual function. These follow-up visits also allow for re-evaluation of contact lens fit and care. Patients with hydrops are seen more frequently until it resolves.

Surgery

The majority of patients with keratoconus can be fitted with contact lenses and their vision significantly improves. When patients become intolerant or no longer benefit from contact lenses, surgery is the next option. If keratoconus is effectively stabilized with corneal crosslinking while patients are still able to achieve adequate visual function with spectacles or contact lenses, further interventions may not be required. Surgical options include intrastromal corneal ring segments (ICRS), corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS), deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), and penetrating keratoplasty (PK).

Non–FDA-approved treatments, which typically have less evidence-based information available on safety and efficacy, include the use of corneal crosslinking experimentally combined with excimer laser treatment, conductive keratoplasty,[25] and/or ICRS.[26] Some surgeons will use phakic intraocular lenses (IOLs) to address high myopia and some astigmatism.

ICRS have also been approved for the treatment of mild to moderate keratoconus in patients who are contact lens intolerant.[26] In these cases, patients must have a clear central cornea and a corneal thickness of >450 μm where the segments are inserted, approximately at the 7 mm optical zone. The advantage of ICRS is that they require no removal of corneal tissue and no intraocular incision, and they leave the central cornea untouched. Most patients will need spectacles and/or contact lenses postoperatively for best vision but will have flatter corneas and easier use of lenses. Different types and sizes of rings and different nomograms have also been developed.[27] [28] However, with ICRS being made of synthetic material, there have been reports of up to a 30% rate of complications, ranging from innocuous to sight threatening.

CAIRS, described in 2018 by Dr Soosan Jacob, proved to be a simple, safe, and effective option for treating keratoconus when combined with collagen crosslinking.[29] Customization of segments was further developed by Dr Awwad.[30] A number of studies have shown CAIRS to be a safe and effective procedure for treating mild to moderate keratoconus with minimal side effects.[31][32][33]

DALK involves the replacement of the central anterior cornea, leaving the patient’s endothelium intact.[34] The advantages are that the risk of endothelial graft rejection is eliminated; there is less risk of traumatic rupture of the globe in the incision, since the endothelium and Descemet membrane and some stroma are left intact; and faster visual rehabilitation. Several techniques are utilized including manual dissection and big-bubble technique to remove the anterior stroma while leaving the Descemet layer and endothelium untouched. However, the procedures can be technically challenging, requiring conversion to penetrating keratoplasty, and postoperatively there is the possibility of interface haze leading to a decrease in BCVA; it is not clear if astigmatism is better treated with DALK versus PK. PK has a high success rate and is the standard surgical treatment with a long track record of safety and efficacy. Risks of this procedure include infection and cornea rejection and risk of traumatic rupture at the wound margin. Many patients after PK may still need hard or gas-permeable contact lenses due to residual irregular astigmatism. Any type of refractive procedure is considered a contraindication in keratoconic patients due to the unpredictability of the outcome and risk of leading to increased and unstable irregular astigmatism.

Surgical Follow-up

Following any corneal surgical procedure, patients need to be followed to complete visual rehabilitation. Most patients still require vision correction with spectacles or contact lenses, and often hard or gas-permeable lenses are required if high levels of astigmatism are present.

All surgical patients need to be followed to ensure wound healing, evaluation for infection, suture removal, and other routine eye care, such as testing for glaucoma, cataracts, and retinal disease. Graft rejection can occur after penetrating keratoplasty, requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment to ensure graft survival.

Complications

- Infection

- Poor wound healing

- Cornea transplant rejection

- Corneal neovascularization

- Graft–host junction thinning

- Glare

- Irregular astigmatism

- High refractive error

Prognosis

With early diagnosis and prompt intervention with corneal crosslinking, patients may retain adequate visual function with spectacle lenses or contact lenses throughout their lifetime. ICRS can provide long-term success for patients with keratoconus, but this is typically in conjunction with contact lens use, and some may ultimately require a corneal transplant to reach their goals of visual rehabilitation. While the prognosis for penetrating keratoplasty in a keratoconic patient is excellent, with most patients able to return to an active lifestyle and the pursuit of personal goals after visual rehabilitation with specialty contact lenses, long-term maintenance therapy with steroid medications may be required. "Progression" of keratoconus, even after corneal surgery, has been reported, but it is not clear how common or to what extent this can occur.

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Huffman JM. Keratoconus. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/keratoconus-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Boyd K, Huffman JM. Corneal Transplantation. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/treatments/corneal-transplantation-list. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Boyd K, Mendoza O, Turbert D. Astigmatism. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/astigmatism-4. Accessed November 17, 2022.

- Cornea Atlas, 2nd Edition. Krachmer, Palay. Elsevier, 2006.

- External Disease and Cornea, Section 8. Basic and Clinical Science Course, AAO, 2006.

- Refractive Surgery, Section 13. Basic and Clinical Science Course, AAO, 2006.

- Ocular Pathology Atlas. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. https://www.aao.org/resident-course/pathology-atlas.

- National Keratoconus Foundation

- National Eye Institute

- National Institutes of Health Clinical Trial Registry

References

- ↑ Sinjab MM. Keratoconus: a historical and prospective review. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2023;16(3):401-414. doi:10.4103/ojo.ojo_70_23

- ↑ Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Fotouhi A. Topographic keratoconus is not rare in an Iranian population: the Tehran Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20(6):385-391. doi:10.3109/09286586.2013.848458

- ↑ Assiri AA, Yousuf BI, Quantock AJ, Murphy PJ. Incidence and severity of keratoconus in Asir province, Saudi Arabia [published correction appears in Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(8):1071]. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(11):1403-1406. doi:10.1136/bjo.2005.074955

- ↑ Millodot M, Shneor E, Albou S, Atlani E, Gordon-Shaag A. Prevalence and associated factors of keratoconus in Jerusalem: a cross-sectional study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18(2):91-97. doi:10.3109/09286586.2011.560747

- ↑ Jonas JB, Nangia V, Matin A, Kulkarni M, Bhojwani K. Prevalence and associations of keratoconus in rural maharashtra in central India: the central India eye and medical study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5):760-765. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.024

- ↑ Xu L, Wang YX, Guo Y, You QS, Jonas JB; Beijing Eye Study Group. Prevalence and associations of steep cornea/keratoconus in Greater Beijing. The Beijing Eye Study. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e39313. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039313

- ↑ Chan E, Chong EW, Lingham G, et al. Prevalence of keratoconus based on Scheimpflug imaging: the Raine study. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(4):515-521. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.020

- ↑ Salomão M, Hoffling-Lima AL, Lopes B, et al. Recent developments in keratoconus diagnosis. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2018;13(6):329-341.

- ↑ Wheeler J, Hauser MA, Afshari NA, Allingham RR, Liu Y. The genetics of keratoconus: a review. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2012;(Suppl 6):001. doi:10.4172/2161-038X.S6-001

- ↑ Gordon-Shaag A, Millodot M, Shneor E, Liu Y. The genetic and environmental factors for keratoconus. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:795738. doi:10.1155/2015/795738

- ↑ Hashemi H, Heydarian S, Hooshmand E, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for keratoconus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cornea. 2020;39(2):263-270.

- ↑ Mazharian A, Panthier C, Courtin R, et al. Incorrect sleeping position and eye rubbing in patients with unilateral or highly asymmetric keratoconus: a case-control study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(11):2431-2439. doi:10.1007/s00417-020-04771-z

- ↑ Grieve K, Ghoubay D, Georgeon C, et al. Stromal striae: a new insight into corneal physiology and mechanics. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13584. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13194-6

- ↑ Rabinowitz YS, Galvis V, Tello A, Rueda D, García JD. Genetics vs chronic corneal mechanical trauma in the etiology of keratoconus. Exp Eye Res. 2021;202:108328. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2020.108328

- ↑ Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Sira M, Bunce C, Wormald R, Collin R. The associations of floppy eyelid syndrome: a case control study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:831-838.

- ↑ Spoerl E, Zubaty V, Raiskup-Wolf F, Pillunat LE. Oestrogen-induced changes in biomechanics in the cornea as a possible reason for keratectasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(11):1547-1550. doi:10.1136/bjo.2007.124388

- ↑ Torres-Netto EA, Randleman JB, Hafezi NL, Hafezi F. Late-onset progression of keratoconus after therapy with selective tissue estrogenic activity regulator. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(1):101-104. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2018.08.036

- ↑ Lee R, Hafezi F, Randleman JB. Bilateral keratoconus induced by secondary hypothyroidism after radioactive iodine therapy. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(5):351-353. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20171031-02

- ↑ Lema I, Sobrino T, Durán JA, Brea D, Díez-Feijoo E. Subclinical keratoconus and inflammatory molecules from tears. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(6):820-824.

- ↑ Gokul A, Patel DV, Watters GA, McGhee CNJ. The natural history of corneal topographic progression of keratoconus after age 30 years in non-contact lens wearers. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(6):839-844.

- ↑ Lema I, Brea D, Rodríguez-González R, Díez-Feijoo E, Sobrino T. Proteomic analysis of the tear film in patients with keratoconus. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2055-2061.

- ↑ Acera A, Vecino E, Rodríguez-Agirretxe I, et al. Changes in tear protein profile in keratoconus disease. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(9):1225-1233. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.105

- ↑ Balasubramanian SA, Mohan S, Pye DC, Willcox MD. Proteases, proteolysis and inflammatory molecules in the tears of people with keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(4):e303-e309. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02369.x

- ↑ Lim L, Lim EWL. A review of corneal collagen cross-linking--current trends in practice applications. Open Ophthalmol J. 2018;12:181-213.

- ↑ Asbell PA. Is conductive keratoplasty the treatment of choice for presbyopia? Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2007;Feb:121-130.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Asbell PA, Holmes-Higgin DK. Intacs corneal ring segments. In: Probst LE, Doane JF, eds. Refractive Surgery: A Color Synopsis. Thieme; 2001.

- ↑ Henriquez MA, Izquierdo L Jr, Bernilla C, McCarthy M. Corneal collagen cross-linking before Ferrara intrastromal corneal ring implantation for the treatment of progressive keratoconus. Cornea. 2012;31(7):740-745. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e318219aa7a

- ↑ Renesto Ada C, Melo LA Jr, Sartori Mde F, Campos M. Sequential topical riboflavin with or without ultraviolet a radiation with delayed intracorneal ring segment insertion for keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):982-993.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.014

- ↑ Jacob S, Patel SR, Agarwal A, Ramalingam A, Saijimol AI, Raj JM. Corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) combined with corneal cross-linking for keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2018;34(5):296-303. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20180223-01

- ↑ Awwad ST, Jacob S, Assaf JF, Bteich Y. Extended dehydration of corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments to facilitate insertion: the corneal jerky technique. Cornea. 2023;42(11):1461-1464. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000003328

- ↑ Haciagaoglu S, Tanriverdi C, Keskin FFN, Tran KD, Kilic A. Allograft corneal ring segment for keratoconus management: Istanbul nomogram clinical results. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022;33(2):689-696. doi:10.1177/11206721221142995

- ↑ Kozhaya K, Mehanna CJ, Jacob S, Saad A, Jabbur NS, Awwad ST. Management of anterior stromal necrosis after polymethylmethacrylate ICRS: explantation versus exchange with corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments. J Refract Surg. 2022;38(4):256-263. doi:10.3928/1081597X-20220223-01

- ↑ van Dijk K, Parker J, Tong CM, et al. Midstromal isolated Bowman layer graft for reduction of advanced keratoconus: a technique to postpone penetrating or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(4):495-501. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5841

- ↑ Bisbe L, Deveney T, Asbell PA. Big bubble keratoplasty. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2009;4(5):553-561.