West African Crystalline Retinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

West African Crystalline Maculopathy (WACM)

Disease

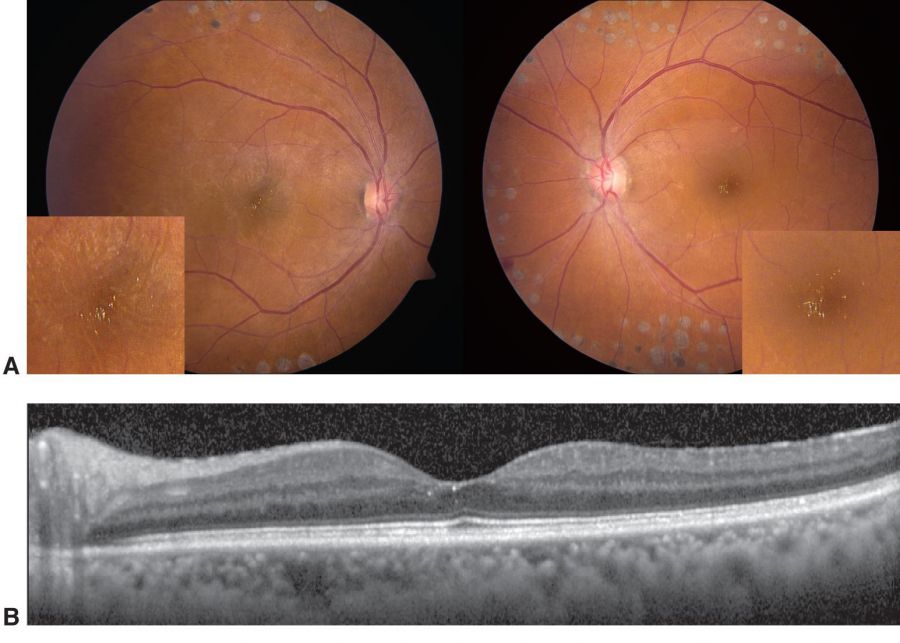

West African Crystalline Maculopathy is an asymptomatic, asymmetric, bilateral or unilateral crystalline maculopathy characterized by focal depositions of birefringent yellow green crystals in the fovea. It was first described by David Sarraf et. al. in 2003 among 6 unrelated late middle aged adults (54-69 years) from the Igbo tribe of southeast Nigeria. [1] [2]

Etiology

The pathophysiology and the composition of deposits are unknown.

The affected tribes/geographic origins include

- Igbo (southeast Nigeria)[1]

- Ibibio, Yoruba, and Delta (Nigeria)[3][2]

- Bassa (Liberia)[3]

- Guinea[4]

- Cameroon[5]

- Akan, Ewe, and Ashanti (Ghana)[2]

- Creole and Corno (Sierra Leone)[2]

- A possible[6] case from Egypt[7]

Several factors have been postulated, including toxic-chloroquine treatment and kola nut intake. [1] Other possibly related history may include history of general anesthesia, malaria, West African foods including cassava, palm oil, afanga greens, eddo greens, plantains, and pumpkin greens.[8][2][3] If an ingested substance is responsible for the crystal deposition, it is likely that there was an elevated metabolic load of the offending substance for multiple years prior to presentation in the macula. [2]

Genetic- Most cases were noted in unrelated individuals and examined family members did not show the characteristic changes.[8] An underlying metabolic abnormality related to genetic pre-disposition cannot be ruled out.[9] Also, an environmental effect may also be probable.[2]

Degenerative-considering the fact that cases were reported in patients who are at least in their fifth decades.

Vascular- Many patients have associated vascular diseases including diabetes and diabetic retinopathy with or without diabetic macular edema, sickle cell disease, retinal venous occlusion, and familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.[2] A possible role of defect in blood retinal barrier has been proposed.[2] Unilateral or asymmetric presentation may be related to unilateral uveitis[4] or retinal vascular disease.[8]

General Pathology

There are many hypotheses regarding the genesis of these crystals, notably that there is a break down of the blood retinal barrier facilitating the entry of innately or environmentally derived crystals.[1][8][4] Some hypothesize the pathophysiology involves Muller cell dysfunction leading to inner blood retinal barrier disruption. [10]These crystals may evolve over a period of months. [2]

Primary Prevention

There is currently no preventive measure for this disease.

Diagnosis

West African Crystalline Maculopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion, based on the clinical appearance of the foveal crystals in a West African patient.

History

Pertinent points to be considered are the presenting age of the patient, West African origin, and dietary habits with regard to intake of kola nuts and local African vegetables including rhubarb.[3] Patient’s with WACM generally present between the ages of 40 and 70.[8] Medical history is important including treatment for malaria and medication history with use of chloroquine, canthaxanthin, tamoxifen, nitrofurantoin, injection of intravenous drugs (talc), use of anesthetics, and use of methoxyflurane.[1][3] History of prior ocular surgery, retinal detachment or any systemic diseases especially diabetes mellitus, hypertension and renal disease should also be taken.[1][3][2][8] History regarding pre-existing ocular disease especially retinal vascular disease or inflammatory disease is also important. [8] Current evidence is insufficient to elucidate a genetic component to WACM as no ocular pathologies are generally found in family members. [11][3][8]

Physical examination

A thorough ophthalmological examination including ocular surface examination, anterior and posterior segment evaluation should be done. Visual acuity can remain unaffected or be reduced.[1][3] Fundus biomicroscopy reveals clusters of birefringent yellow- green crystals in the foveal region at the inner retina.[1][2] The presence of crystals is commonly bilateral but unilateral cases have also been described.[2] The foveocentricity described in early reports may have been coincidental as these crystals have been shown to localize with commonly present lipid exudates, even if the exudates are extrafoveal.[3] Features of pre existing diseases like those of diabetic retinopathy and retinal vascular occlusions may be present.[2] Additionally, both color vision tests and Humphrey visual field tests remain normal.[1] WACM is different compared to other types of crystalline retinopathies; these crystals are generally found in foveal avascular zones.[3] In addition, they are not found outside the temporal vascular arcades, do not have annular parafoveal deposition, and do not have a periarteriolar predilection, or concomitant black ringlet or plaque lesions.[3]

Symptoms

West African Crystalline Maculopathy is usually asymptomatic. A decrease in vision may be observed as a consequence to retinal vascular diseases involving the macula which may be associated with the crystalline maculopathy.

Diagnostic procedures

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) plays a critical role in the diagnosis of WACM. Bilateral or unilateral asymmetric intra retinal refractile deposits in the foveal region can be appreciated using high resolution OCT. [2] Normal OCT with normal autofluorescence has been described.[12] Some studies have localized the crystals to the inner retinal layers[11] , internal limiting membrane, while others have localized the crystals to Henle's layer[2], outer plexiform layer, or the nuclear layer.[4] Cystic fluid in the macular region can be present as a sign of associated diseases.[4] The use of a rotating polarizing filter can show that these crystals are birefringent.[2] Fundus and fluorescein angiography (FFA) are usually unremarkable[1] and shows no angiographic correlates of the crystals, but may show leakage from neovascularization.[3] Electrophysiological tests are also usually normal though abnormal photopic and scotopic response may be present.[1]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of crystalline maculopathy

Systemic disease -

- Oxalosis

- Cystinosis

- Hyperornithinemia

- Sjogren-Larsson syndrome

- Kjellin Syndrome

Drug induced-

- Talc

- Tamoxifen

- Canthaxanthine

- Nitrofurantoin

- Methoxyfluorane

Ocular pathology-

- Idiopathic parafoveal telangiectasias

- Bietti's crystalline dystrophy

- Calcified macular drusen

- Chronic retinal detachment

Management

Complications

West African crystalline maculopathy is a unique form of crystalline maculopathy that is asymptomatic and has no sequelae.[1]

Prognosis

The prognosis for this disease is good as it is not known to cause visual impairment. The severity of crystalline deposits may not affect vision. The deposits may rapidly evolve over months or may even regress/reabsorb over years.[8]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Sarraf D, Ceron O, Rasheed K, Drenser KA, Casey R. West African crystalline maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(3):338-342. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.3.338

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 Rajak SN, Mohamed MD, Pelosini L. Further insight into West African crystalline maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(7):863-868. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.129

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Browning DJ. West African crystalline maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):921-925. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.030

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Tsui E, Thareja T, Modi YS. Asymmetric Presentation of West African Crystalline Maculopathy. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(6):485. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2017.06.011

- ↑ Drenser K, Sarraf A, Jain A, Small K. Crystalline retinopathies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51(6):535-549.

- ↑ Dhital A, Mohamed M. A case of African crystalline maculopathy. Eye (Lond). 2012;26(4):615-617. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.251

- ↑ Hammoudi DS, Mandelcorn E, Navajas EV, Mandelcorn M. A case of African crystalline maculopathy. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(6):825-827. doi:10.1038/eye.2011.30

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Kung JS, Leng T. West African Crystalline Maculopathy in Sickle Cell Retinopathy. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2015;2015:910713. doi:10.1155/2015/910713

- ↑ Kung JS, Leng T. West African Crystalline Maculopathy in Sickle Cell Retinopathy. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2015;2015:910713. doi: 10.1155/2015/910713. Epub 2015 Dec 16. PMID: 26788391; PMCID: PMC4695655.

- ↑ Kovach JL, Isildal H, Sarraf D. Crystalline retinopathy: Unifying pathogenic pathways 399 of disease. Surv Ophthalmol 2019; 64:1-29.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Weng CY, Morales JF, Gupta I. West African Crystalline Maculopathy in a Nigerian Woman. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):390. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.022

- ↑ Umunakwe OC, Ali MH, Bains N, Matthews JD, Fekrat S. Multimodal Imaging of West African Crystalline Maculopathy in an Igbo Man. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2021 Jun 29;6(3):243-245.