Bietti Crystalline Dystrophy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

2018 ICD-10 Code: H35.53: Other dystrophies primarily affecting the sensory retina

Disease

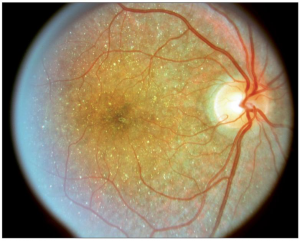

Bietti’s Crystalline Dystrophy (BCD), is a rare autosomal recessive ocular disease that involves yellow-white crystalline lipid deposits in the retina and sometimes cornea, degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and sclerosis of the choroidal vessels. Progression of the disease ultimately results in reduced visual acuity, night blindness, visual field loss, and impaired color vision. Onset of the disease can occur from early teenage years to third decade of life, but can also occur beyond the third decade. As the disease progresses, decreases in peripheral acuity, central acuity, or both ultimately result in legal blindness in most patients.

BCD was first described by Italian Ophthalmologist Dr. G.B. Bietti in 1937.[2] There have been around 100 reported cases documented in the literature (OMIM 210370).

Genetics

The mode of inheritance for BCD is autosomal recessive. BCD involves the pathologic variant of the CYP4V2 gene.[3] Carrier testing should be considered for at- risk relatives.

Risk Factors

Asians, especially those of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean ethnicities, have been found to have a relatively higher incidence of BCD.[4]

Pathophysiology

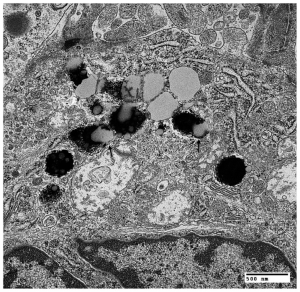

The pathophysiology of BCD is still unclear. However, biallelic pathologic variations in CYP4V2 have been implicated in the disease. CYP4V2 enzyme has been shown to play a role in fatty acid and steroid metabolism. Dysfunctional lipid metabolism may result in complex lipid retinal, corneal, and conjunctival intracellular deposits in crystalline form due to accumulation of fatty acids.[5] [6] In patients with BCD, lipid inclusions are found systemically, suggesting possible dysfunctional lipid metabolism elsewhere in the body as well.[7]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BCD is based on ophthalmic evaluation of numerous small glistening yellow-white retinal crystalline deposits in the retinal with or without crystalline deposits in the cornea, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy, pigment clumping, and choroidal vessels sclerosis.[8] The corneal crystals are usually isolated in the subepithelial and anterior stroma of the peripheral cornea (25-33%).[9] Reflective white- yellow deposits have also been described in the crystalline lens in patients with BCD.[10]

CYP4V2 is only moderately expressed in the cornea and the conjunctiva; thus, ocular surface findings are not required for diagnosis.[6] Diagnostic tools include electroretinography for evaluating degree of rod and cone dysfunction, Humphrey visual field (HVF) testing for visual field deficits, spectral domain ocular coherence tomography (OCT) for identifying reflective dots, in vivo confocal microscopy to visualize hyperreflective bodies in the cornea, and specular microscopy of the cornea.[11][12]

If clinical features are equivocal, the disease can be confirmed by the identification of pathologic variants in CYP4V2 by molecular genetic testing.[13]

Symptoms

Typically patients with BCD begin noticing symptoms between the second and third decades of life.[10] Patients experience a progressive reduction in visual acuity, nyctalopia, and visual field loss. Occasionally, color vision may also be impaired. Visual deficits can progress at different rates in each eye, and the severity and rate of progression varies widely among affected individuals. Over time patients, particularly in the fifth or sixth decade, can become legally blind.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for BCD includes other diseases that involve crystalline deposits in the retina such as:

- Retinitis Pigmentosa

- Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 and type 2

- Cystinosis

- Infectious Crystalline Keratopathy

- Sjogren-Larsson Syndrome

- Drug Toxicity from agents such as tamoxifen, talc retinopathy, methoxyflurane, and canthaxanthin

Management

Historically, standard of care for BCD patients include follow-up with an ophthalmologist for a yearly exam to monitor disease and to watch for macular hole, edema, atrophy, and choroidal neovascularization (CNV). Anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injection has been described favorably in the treatment of BCD complicated by CNV.[15]

Standard of care for BCD patients with vision impairment includes referral to low vision specialists or state services for the blind.

Genetic testing is available for those that have immediate family diagnosed with BCD in order to identify abnormal CYP4V2 genes. Genetic counseling is offered for those with diagnosed BCD or BCD carriers for family planning, whereas prenatal testing for BCD is possible but controversial.[11]

Recently, in a first-in-human clinical trial, Wang et al. evaluated the safety and efficacy of gene replacement therapy for BCD[16]. Twelve participants received a subretinal injection of a recombinant AAV2/8 vector carrying the human CYP4V2 gene[16]. The treatment was generally well-tolerated, with 98.6% of the 73 adverse events being mild or moderate and no serious treatment-related toxicities reported. Importantly, visual outcomes were promising: 77.8% of treated eyes improved in best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by day 180, with further gains observed by day 365[16]. Additional functional tests, including electroretinography and visual function questionnaires, supported the observed visual benefits, indicating the potential of this therapy for managing BCD[16].

Prognosis

There is no known cure for this disease. As a result, loss of peripheral visual field and visual acuity can result in legal blindness in patients with the disease.

Conclusion

Bietti’s Crystalline Dystrophy (BCD) is a rare corneo-retinal dystrophy that is characterized by deposition of yellow-white crystals in the retina and sometimes the cornea, degeneration of the retina, and sclerosis of the choroidal vessels that results in the progressive loss of peripheral visual acuity and night blindness. There is currently no specific treatment for BCD. However, early diagnosis and referral to low-vision specialists can help with management of patients with this disease.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Bietti crystalline dystrophy. https://www.aao.org/image/bietti-crystalline-dystrophy Accessed September 19, 2019.

- ↑ Bietti G. Ueber familiaeres Vorkommen von 'Retinitis punctata albescens' (verbunden mit 'Dystrophia marginalis cristallinea corneae'), Glitzern des Glaskoerpers und anderen degenerativen Augenveraenderungen. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 99: 737-757, 1937.

- ↑ Lin J, Nishiguchi KM, Nakamura M, Dryja TP, Berson EL, Miyake Y. Recessive mutations in the CYP4V2 gene in East Asian and Middle Eastern patients with Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy. J Med Genet. 2005;42(6):e38.

- ↑ Kaiser-Kupfer MI, Chan CC, Markello TC, Crawford MA, Caruso RC, Csaky KG, Guo J. Clinical biochemical and pathological correlations in Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy. Am J OphthalmoI 1994; 118: 569–582.

- ↑ Lee J, Jiao X, Hejtmancik JF, et al. The metabolism of fatty acids in human Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(8):1707-14.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Garcia-Garcia GP, Martinez-Rubio M, Moya-Moya MA, Perez-Santonja JJ, Escribano J. Current perspectives in Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Clin Ophthalmol 2019;13:1379-99.

- ↑ Wilson DJ, Weleber RG, Klein ML, Welch RB, Green WR. Bietti's crystalline dystrophy. A clinicopathologic correlative study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(2):213-21.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Furusato E, Cameron JD, Chan CC. Evolution of Cellular Inclusions in Bietti's Crystalline Dystrophy. Ophthalmol Eye Dis. 2010;2010(2):9-15.

- ↑ Krachmer J, Mannis M, Holland E: CORNEA, 4th ed.Elsevier Mosby, 2017, 251-264.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Sayadi, J. & Mekni, M. Crystals lens deposits: a rare occurrence in Bietti corneo-retinal dystrophy. Pan Afr Med J 43, 7 (2022).

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Vargas M, Mitchell A, Yang P, Weleber R. Bietti Crystalline Dystrophy. GeneReviews. 2012.

- ↑ Dai H, Zhang Y, Wu X, Li Y, Wang L, Li G. Corneal deposits and nerve alterations in Bietti Corneoretinal Crystalline Dystrophy imaged using in vivo confocal microscopy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Jul 2023;261(7):1941-1949. doi:10.1007/s00417-023-05987-5

- ↑ Xiao X, Mai G, Li S, Guo X, Zhang Q. Identification of CYP4V2 mutation in 21 families and overview of mutation spectrum in Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;409(2):181-6.

- ↑ Mansour AM, Uwaydat SH, Chan CC. Long-term follow-up in Bietti crystalline dystrophy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17(4):680-2.

- ↑ Wang, W., Chen, W., Bai, X., & Chen, L. (2020). Multimodal imaging features and genetic findings in Bietti crystalline dystrophy. BMC Ophthalmol, 20(1), 331. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-020-01545-3

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Wang, J., Zhang, J., Yu, S. et al. Gene replacement therapy in Bietti crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy: an open-label, single-arm, exploratory trial. Sig Transduct Target Ther 9, 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01806-3

- Jiao X, Munier FL, Iwata F, et al. Genetic linkage of Bietti crystallin corneoretinal dystrophy to chromosome 4q35. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(5):1309-13.

- Mamatha G, Umashankar V, Kasinathan N, et al. Molecular screening of the CYP4V2 gene in Bietti crystalline dystrophy that is associated with choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2011;17:1970-7.

- Mataftsi A, Zografos L, Millá E, Secrétan M, Munier FL. Bietti's crystalline corneoretinal dystrophy: a cross-sectional study. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa). 2004;24(3):416-26.

- O’Neill M, McKusick V. #210370 Bietti Crystalline Corneoretinal Dystrophy; BCD. OMIM. 2015

- Sahu DK, Rawoof AB. Bietti's crystalline dystrophy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2002;50(4):330-2.