Trichiasis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Trichiasis ICD 10: H02.059

Disease

Trichiasis results from eyelashes that are misdirected against the ocular surface. This is most often a consequence of eyelid inflammation and scarring, although it can be a presenting symptom of an eyelid margin malignancy as well. Constant irritation can lead to eye pain, vision changes, corneal abrasions, or corneal ulcers. Although this condition is often idiopathic, certain conditions can contribute to this development, such as infection, inflammation, involutional changes, or trauma. Before removing the malaligned contact between the eyelashes and the ocular surface, diagnosis of and understanding the underlying cause of trichiasis is essential.

History

Trichiasis has been recognized since the time of Hippocrates (460-370 BCE).[1] Although he provided no definition, multiple treatments at that time were described including epilation and a surgical procedure using a needle and thread to correct eyelid position.[1] Multiple other descriptions and treatments can be found from the 1st to 7th Century CE including Dioscorides, Galen, Oribasios and Aetius.[1]

More recent advances in the surgical correction of trichiasis include intermarginal split lamella with graft, first described by Van Millingen in 1887, split margin division with removal of lid lamella containing the misdirected eyelashes and wound surface coverage with a skin flap, described by steinkogler in 1986, and split margin at the gray line with resection of the lash-bearing anterior lamella of the eyelid with glue to position the skin over the wound, described by Wojno in 1992.[2][3][4]

Eyelid Anatomy

The eyelids are essential for the protection of ocular structures and tear film distribution. The structure of the eyelid can be broken down into two conceptual layers, the anterior and posterior lamella. The different lamellae of the eyelid are separated by the grey line which is composed of the muscle of Riolan, a thin strip of pretarsal orbicularis muscle. The anterior lamella is composed of the skin, orbicularis muscle, and skin appendages (cilia, eccrine glands, apocrine glands). The posterior lamella includes the tarsal plate, meibomian glands, and conjunctiva. There are approximately 100-150 cilia in the upper lid and 50-75 cilia in the lower lid.[5]

Clinical Manifestation

Patients may present with eye pain, foreign body sensation, eye redness, tearing, vision changes, photophobia, and decreased vision. An ocular examination may show malpositioned cilia, entropion of the upper and/or lower eyelids, conjunctival injection, superficial punctate keratopathy, corneal abrasion, keratitis, keratinization or blindness.[6]

Pathophysiology

Normally, the eyelashes are directed away from the globe. Any factor that causes the misalignment of the eyelashes to make contact with the cornea or conjunctiva can cause trichiasis. Note well that these patients have normal lid margin position.[7] Different causes include chronic blepharitis, trauma, previous surgery, chemical burns, infection, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, or distichiasis (ferreira). Trichiasis can be classified as either minor (fewer than 5 cilia) or major (5 or more cilia).[8] Subsequently, the eyelashes can cause damage to the delicate layers of the cornea and decrease the corneal transparency leading to light scattering and vision changes. Ultimately, the chronic irritation can lead to keratinization, corneal thinning, perforation, and possible blindness.[9]

Epidemiology

While the frequency of trichiasis is not known, trachoma is the most common cause of infectious blindness worldwide.[10] It is the result of infection by the intracellular obligate bacteria Chlamydia Trachomatis and is thought to affect approximately 10 million people.[11] As part of the World Health Organization’s effort to eliminate trachoma by 2020, they estimate there is presently about 3.2 million surgery backlog. Women are four times more affected than males.[12] Eyelash trichiasis may also be a result of topical prostaglandin use, or other chronic eyelid/eyelash inflammation.

Risk Factors

For development of trichiasis[7]

Inflammatory

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

- OCP

- Stevens-Johnson/TEN

- Medicamentosa

- Rosacea

- Blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction

- Actinic keratosis

Infectious

Traumatic

- Eyelid laceration

- Post-surgical

Anatomic

Other

- Topical ocular medications (specifically glaucoma medications)

Management

Management is dependent on the underlying pathophysiology, the extent of trichiasis, and the type of lashes affecting the globe. If the patient is on a topical prostaglandin drop that may cause eyelash misdirection, they should discuss with their ophthalmologist whether the medicine can be changed.

Medical Management

Eye lubrication, contact lenses, and mechanical epilation.[7] Patients with trichiasis secondary to trachoma benefited significantly from trichiasis recurrence from post-op single dose Azithromycin compared to topical Tetracycline for 6 weeks (P = 0.047).[13]

Surgery

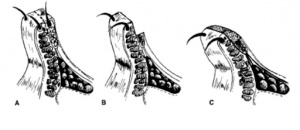

Traditional Techniques

A study by Ferraz et al. comparing two common surgical approaches to treatment - intermarginal split lamella with graft (ISLG) or lid lamella resection (LLR) - showed that LLR had higher complete success rates, less repeat surgeries, and was a simpler technique (P<0.05).[2]

Cryosurgery

Many use alternative treatment options secondary to the damage cryosurgery may inflict on surrounding tissue like the lid margin transitional epithelium and tarsus.[7]

Buccal Membrane Grafting

This approach is generally reserved for refractory trichiasis. The eyelid margin is incised and a small portion of the posterior margin is removed that contains the malaligned eyelash. Then, this defect is replaced with a buccal membrane graft in the posterior margin to prevent abnormal scarring that can lead to cicatricial entropion.

Application of 0.02% mitomycin C in conjunction with radiofrequency ablation can help prevent the regrowth of eyelashes.[14]

Electrolysis

Lashes that are localized, as opposed to diffuse, respond well to electrical ablation. Because the procedure requires the placement of an electrolysis needle into the hair follicle, this technique is more difficult to use with trichiasis with lanugo hair.[6]

Laser Ablation

Recommended particularly with patients with co-morbidity of ocular pemphigoid, where minimal inflammation is important to prevent exacerbation of the disease. This technique is best for a few scattered eyelashes. Although, a challenge is to position the eyelid such that the laser can reach the full depth of the eyelash follicle.[15]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kostopoulou O, Grzybowski A, Trompoukis C. Trichiasis in Ancient Times. Clin Dermatol. 2016 Jul-Aug;34(4):521-3. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.01.001.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ferraz LC, Meneghim RL, Galindo-Ferreiro A, et al. Outcomes of two surgical techniques for major trichiasis treatment. Orbit. 2018;37(1):36-40. doi:10.1080/01676830.2017.1353108.

- ↑ Steinkogler FJ. Treatment of upper eyelid entropion. Lid split surgery and fibrin sealing of free skin transplants. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;2(4):183–187.

- ↑ Wojno TH. Lid splitting with lash resection for cicatricial entropion and trichiasis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8(4):287–289. doi:10.1097/00002341-199212000-00008.

- ↑ Tyers AG, Collin JRO. Colour Atlas of Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery. [Electronic Resource]. [Oxford] : Elsevier, 2018.; 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ferreira I, Bernardes T, Bonfioli A. Trichiasis. Semin Ophthalmol, Informa UK, London, UK (2010), pp. 66-71

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Srinivasan A, Kleinberg T. Trichiasis: Lashes Gone Astray. Review of Ophthalmology. 2015;22(5):68.

- ↑ Kirkwood B, Kirkwood R. Trichiasis: characteristics and management options. Insight, 36 (2010), pp. 5-9

- ↑ Meek KM, Knupp C. Corneal structure and transparency. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2015;49:1-16. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.07.001.

- ↑ Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. The Lancet Global health 2013; 1(6): e339-49.

- ↑ Burton M, Solomon A. What’s new in trichiasis surgery? Community Eye Health Journal 2004; 17(52): 52–53.

- ↑ WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020 Eliminating trachoma: accelerating towards 2020. Accessed from: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/sites/all/themes/report-2016/PDF/GET2020_2016_EN.pdf

- ↑ West S, West E, Alemayehu W, et al. Single-dose azithromycin prevents trichiasis recurrence following surgery - Randomized trial in Ethiopia. Arch Ophthalmol. 124(3):309-314.

- ↑ Kim G, Yoo W, Kim S, et al. The effect of 0.02% mitomycin C injection into the hair follicle with radiofrequency ablation in trichiasis patients. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014;28(1):12-18. doi:10.3341/kjo.2014.28.1.12.

- ↑ Bartley GB, Lowry JC. Argon laser treatment of trichiasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 113(1):71-74. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)75756-3.