Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) of Theodore is a rare chronic inflammatory disease of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, limbus and upper cornea of unknown etiology. This disease has been associated with thyroid dysfunction, keratoconjunctivitis sicca and rheumatoid arthritis. Multiple treatment modalitites have been described but there is not a gold standard.

Disease Entity

ICD-10:

- H16.299 - Other keratoconjunctivitis, unspecified eye

- H16.291 - Other keratoconjunctivitis, right eye

- H16.292 - Other keratoconjunctivitis, left eye

- H16.293 - Other keratoconjunctivitis, bilateral

ICD-9:

- 370.40 - Keratoconjunctivitis, unspecified

Disease

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) was described by Frederick Theodore in 1963 in a group of patients without evidence of infection, characterized by marked inflammation of the upper tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva, fluorescein staining of the cornea and upper limbus, positive staining with lissamine green or rose bengal of the superior bulbar conjunctiva adjacent to the limbus, proliferation and redundancy of superior limbic conjunctiva, and filament formation in the limbic area and the upper part of the cornea[1]. The age of presentation is around the sixth decade of life, affecting women more often than men (ratio 3:1)[1]. A Mexican case series reported a higher frequency of presentation in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 5.4:1[2]. An association between SLK and thyroid dysfunction has been reported in up to of 30% of the patients[3][4][5]. An association with ocular graft-versus-host-disease is also established, though the true incidence is unknown[6]. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca has also been reported to be present in 25% of patients[1][2][5].

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiology and pathogenesis of the disease is unknown. SLK may represent the final manifestation of a variety of pathophysiological pathways and disease entities. One of the most propagated theories is the one proposed by Wright. This theory suggests that the initial component leading to the development of SLK is a constant friction between the superior bulbar and tarsal conjunctiva caused by excessive laxity[7]. However, like other theories previously proposed, such as infectious, immunogenic and allergic, it lacks of sufficient and convincing evidence to sustain itself as a unique unifying mechanism in the development of the disease[8].

Histopathological studies of the conjunctiva of SLK affected patients have typically shown keratinization of epithelial cells with dyskeratosis, acanthosis and nuclear balloon degeneration. Furthermore, by microscopic analysis, a stromal infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, plasma cells, mastocytes and lymphocytes has been reported[9][10]. Watanabe et al. showed decreased levels of mucin-like glycoprotein on immunofluorescent staining of 9 study eyes with keratinized superior bulbar conjunctival epithelium, and standardization of such levels when compared to normal control subjects after treatment with topical vitamin A or bandage contact lens[11]. Matsuda et al. detected abnormal differentiation and hyperproliferation of the conjunctival epithelium associated with increased expression of cytokeratins 10,13,14 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Additionally, the same group showed upregulation of transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGF-β2) and the tenascin 13. Both factors can be induced by mechanical trauma, supporting the theory of microtrauma as the possible origin of SLK[12].

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The disease is characterized by unilateral or bilateral, insidious foreign body sensation, photophobia, excessive blinking and ocular burning and pain. When prompted, patients can often specifically localize the physical location of their symptoms to the superior aspect of their adnexa. In a case series of 45 patients, most frequent symptoms reported were: foreign body sensation (71.1%), burning sensation (68.9%), pruritus (46.6%) and dry eye sensation (31.1%), among others[2].

Physical Examination

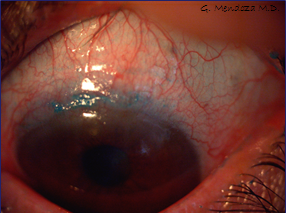

The ophthalmological examination is characterized by micro-papillary reaction in the upper tarsal conjunctiva, redundancy and laxity of the upper bulbar conjunctiva, sectorial conjunctival hyperemia, keratinization and ciliary injection. In some cases, there is noticeable thickening of the superior bulbar conjunctiva which stains positive with fluorescein, rose bengal and lissamine green in a punctate focal pattern[1]. In a case series of 45 patients, 100% had ciliary injection in the upper bulbar conjunctiva, 73.3% showed corneal erosions in the upper quadrants, 68.9% superior tarsal papillae, 22.2% diffuse superficial corneal erosions, 15.5% conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid edema in 13.33%, among others[2].

Diagnostic procedures

Careful slit lamp examination of the superior bulbar conjunctival and upper tarsal conjunctiva are paramount. Evaluation of the upper bulbar conjunctiva, looking for foldings, hyperemia, redundancy, and filament formation. Fluorescein and lissamine green, or rose bengal staining can be extremely useful. Schirmer testing can be useful if keratoconjunctivitis sicca is suspected. Examination for thyroid orbitopathy can also be useful.

Laboratory test

Depending on clinical findings, thyroid function tests may be helpful. Additional testing for autoimmune serologic tests like, anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B) antibodies, and cyclic citrullinated-peptide antibodies can be considered if suspicious for Sjogren's Syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis. Medical evaluation by a rheumatologist or endocrinologist is recommended in case of suspected associated systemic disease.

Differential diagnosis

- Allergic conjunctivitis

- Dry eye syndrome

- Episcleritis

- Floppy eyelid syndrome

- Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

- Ocular surface squamous neoplasia

- Thyroid Ophthalmopathy

- Trachoma

- Viral Conjunctivitis

Management

Medical therapy

There is not a gold standard in the treatment of SLK. Many different therapeutic modalities have been reported, including topical steroids, topical tacrolimus[13], topical rebamipide[14], topical silver nitrate, therapeutic soft contact lens[15], scleral lens[6], lacrimal puncta occlusion[16], topical vitamin-A[17], topical cyclosporine-A 0.5%[18], ketotifen fumarate[19], autologous serum[20], cromolyn sodium[21], lodoxamide tromethamine[22], botulinum injection in the muscle of Riolan[23], and supratarsal triamcinolone injection[24], all of which have shown variable therapeutic responses.

Medical follow up

Partial disease resolution is common. Patients may require chronic medical therapy. A referral to a specialist may be indicated, especially for coexisting systemic pathology.

Surgery

Fraunfelder et al. reported a case series of seven eyes treated with nitrogen liquid cryotherapy applied with double freeze-thaw technique, this technique is safe but retreatments may be necessary in about one third of eyes[25]. Upper conjunctival resection with or without thermal cauterisation and with or without amniotic membrane implantation has variable results in the treatment of SLK[26] [27] [19][28][29]. Long-term results are more variable and partial disease resolution and recurrence may require additional medical attention.

Prognosis

Remissions and exacerbations tend to diminish in frequency as age increases.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Theodore FH. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon 1963;42(2):25-28.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mendoza-Adam G, Rodríguez-García A. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) and its association to systemic diseases. Rev. Mex. Oft. 2013;87(2):93-99.

- ↑ Cher I. Clinical features of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis in Australia. A probable association with thyrotoxicosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1969;82(5):580-586.

- ↑ Theodore FH. Comments on findings of elevated protein-bound iodine in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis: part I. Arch Ophthalmol 1968;79: 508.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Tenzel RR. Comments on superior limbic filamentous keratitis: part II. Arch Ophthalmol 1968;79:508.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Sivaraman KR, Jivrajka RV, Soin K, et al. Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis-like Inflammation in Patients with Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Ocul Surf. 2016;14(3):393-400. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2016.04.003

- ↑ Wright P. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1972;92(1):555-560.

- ↑ Wilson FM 2nd, Ostler HB. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1986;26(4):99-112.

- ↑ Eiferman RA, Wilkins EL. Immunological aspects of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol 1979;14(2):85-87.

- ↑ Sun YC, Hsiao CH, Chen WL, et al. Conjunctival resection combined with Tenon layer excision and the involvement of mast cells in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;145(3):445-452.

- ↑ Watanabe H, Maeda N, Kiritoshi A, et al. Expression of a mucin-like glyco-protein produced by ocular surface epithelium in normal and keratinized cells. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124(6):751-757.

- ↑ Matsuda A, Tagawa Y, Matsuda H. Cytokeratin and proliferative cell nuclear antigen expression in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res 1996;15(10):1033-1038.

- ↑ Kymionis GD, Klados NE, Kontadakis GA, Mikropoulos DG. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with topical tacrolimus 0.03% ointment. Cornea. 2013 Nov;32(11):1499-501. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318295e6b9. PMID: 23770977.

- ↑ Takahashi Y, Ichinose A, Kakizaki H. Topical rebamipide treatment for superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis in patients with thyroid eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Apr;157(4):807-812.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.12.027. Epub 2014 Jan 9. PMID: 24412123.

- ↑ Mondino BJ, Zaidman GW, Salamon SW. Use of pressure patching and soft contact lenses in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Arch. Ophthalmol 1982;100:1932.

- ↑ Kabat AG. Lacrimal occlusion therapy for the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis. Optom Vis Sci 1998;75:714-718.

- ↑ Ohashi Y,Watanabe H., Kinoshita S, Hosotani H, Umemoto M, and Manabe R. Vitamin A eyedrops for superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol 1988; 105:523-527.

- ↑ Perry H, Doshi-Carnevale S, Donnenfeld E, Kornstein H. Topical Cyclosporine A 0.5% as a Possible New Treatment for Superior Limbic Keratoconjuntivitis. Ophthal 2003; 110:1578-81.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 Udell IJ, Kenyon KR, Sawa M, Dohlman CH.: Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis by thermocauterization of the superior bulbar conjunctiva. Ophthalmology 1986,93:162-6.

- ↑ Goto E, Shigeto S, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K.: Treatment of Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis by Application of Autologous Serum. Cornea 2001;20(8):807-810.

- ↑ Confino J, Brown SI. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis with topical cromolyn sodium. Ann Ophthalmol 1987;19:129-31.

- ↑ Foster S, Feiler LS. Lodoxamide tromethamine treatment for superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol 1995;120:400-401.

- ↑ Chun YS, Kim JC. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with a large-diameter contact lens and Botulium Toxin A. Cornea. Aug 2009;28(7):752-8.

- ↑ Shen YC, Wang CY, Tsai HY, et al. Supratarsal triamcinolone injection in the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. May 2007;26(4):423-6.

- ↑ Fraunfelder FW. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. Feb 2009;147(2):234-238.e1.

- ↑ Zoroquiain P, Sanft DM, Esposito E, Cheema D, Dias AB, Burnier MN Jr. High Inflammatory Infiltrate Correlates With Poor Symptomatic Improvement After Surgical Treatment for Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2018 Apr;37(4):495-500. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001508. PMID: 29346129.

- ↑ Gris O, Plazas A, Lerma E, Güell JL, Pelegrín L, Elíes D. Conjunctival resection with and without amniotic membrane graft for the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2010 Sep;29(9):1025-30. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181d1d1cc. PMID: 20539210.

- ↑ Donshik TC, Collin HB, Foster CS, Cavanagh HD, Boruchoff SA. Conjuntival resection treatment and ultraestructural histopathology of superior limbic keratoconjuntivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol 1978;85:101-110.

- ↑ Kheirkhah A, Casas V, Esquenazi S, et al. New surgical approach for superior conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. Jul 2007;26(6):685-91.