Orbital Roof fractures

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Fractures of the roof of the orbit are typically associated with trauma to the forehead/frontal bone are are often extensions of superior orbital rim fractures. Isolated non-displaced orbital roof fractures most commonly seen in children and rarely require surgical intervention.

Disease

Orbital Roof Fracture (ICD - # 801.01)

Etiology

Isolated orbital roof fractures in adults are uncommon, comprising 12-19% of all orbital wall fractures. Most roof fractures are associated with other orbital/facial fractures and result from significant head trauma, as a high degree of force is required to fracture this portion of the orbit. The frontal sinus is often involved. Large comminuted displaced orbital roof fractures are often associated with severe head and face trauma (including higher rates of intracranial hemorrhage) and these fractures are therefore often managed via a multi-disciplinary approach with members of the neurosurgery and otolaryngology services. In children, fractures of the orbital roof may be seen in isolation and may arise from much less significant trauma.

Risk Factors

Patients who sustain any trauma to the head are at risk for orbital roof fractures. In adults, the traumatic event is typically associated with greater energy transfer (e.g. unhelmeted motorcycle accident or falls from height) than in children.

General Pathology

In adults, the roof of the orbit is often paper thin in the area of the frontal sinus. The floor of the frontal sinus is the roof of the orbit, comprised of the frontal bone and lesser wing of the sphenoid. Trauma to the frontal bar of the superior orbital rim can cause a buckling of this bone in addition to fractures of the contralateral orbit. Orbital emphysema is common when the frontal sinus is involved. In addition, extension of fractures of the cranial vault may involve the roof of the orbit with subsequent cerebral spinal fluid leakage. Delayed findings can include pulsatile exophthalmos with orbital encephalocele. Children are more likely to have isolated linear fractures of the orbital roof similar to the greenstick fractures seen in the orbital floor.

Pathophysiology

The same hydraulic and buckling theories that are associated with the orbital floor and medial walls apply to the orbital roof. See Orbital Floor Fractures.

Primary prevention

Prevention is accomplished only by avoiding or mitigating trauma to the head and face. Appropriate protective gear such as full face helmets for high impact sports and other activities may lessen the incidence of orbital roof fractures.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by clinical and radiologic evaluation.

History

Most commonly, patients will report a recent history of trauma to the head and/or face. In children, the parents my note only minor trauma such as butting heads with a sibling on the trampoline.

Physical examination

A formal and complete ophthalmic exam to rule out globe trauma is essential in the examination of all facial/head trauma patients. It is particularly important to document the visual acuity and optic nerve function (e.g. pupillary exam) as early in the exam as possible. In cases of evolving pathology such as an orbital hematoma, serial exams may be necessary. Noted concomitant ocular injuries with orbital roof fractures include a higher prevalence of corneal abrasions, lid lacerations, and afferent pupillary defects suggestive of traumatic optic neuropathy compared to non-roof involving orbital wall fractures. Rates of open globe in with orbital roof fracture range from 4-9.5%. If significant globe trauma is identified (i.e. ruptured globe or retinal detachment), orbital surgery is usually postponed due to the increased risk this places on the damaged globe.

In addition to the formal ophthalmic exam, a complete orbital exam is required. In addition to the pupillary exam, other optic nerve function tests such as red desaturation and color plate testing may aid the examiner. Palpation of the orbital rims may show rim step-offs and other defects. Crepitus with air from the frontal sinus may be seen. Exophthalmometry measurements may reveal proptosis or enophthalmos.

Signs

Signs of orbital roof fractures are similar to those seen with other orbital fractures but may be minimal. Periorbital hematoma and edema are common as are subconjuntival hemorrhage and chemosis. The patient may have ocular misalignment. The patient may have anterior segment findings (e.g. hyphema), ocular misalignment, motility deficits, or an oculocardiac reflex. Proptosis or enophthalmos may be seen and other head and facial trauma signs such as lacerations are common as well. If a unilateral traumatic optic neuropathy is present, the patient with have a relative afferent pupillary defect (rAPD). This may also be present in the setting of a retrobulbar hemorrhage which can be seen in these patients and requires urgent intervention.

Symptoms

In cases of relatively minor trauma, the patient may have no complaints. Other symptoms are similar to those seen with other orbital fractures including poor vision, double vision, pain with eye movement and pain with nose blowing. It is important to note that a higher proportion of orbital roof fracture patients are unable to give a reliable subjective history (e.g. due to patient GCS), compared to patients with non-roof involving orbital wall fractures. With severe trauma, the patient may be sedated and intubated on initial exam by the Ophthalmologist.

As previously noted, herniation of the intracranial tissues through the roof fracture may present as pulsating proptosis. Imaging would be indicated to rule out an encephalocele, meningocele, or meningoencephalocele.

Clinical diagnosis

With the typical signs and symptoms outlined above, the clinician must have a high suspicion for orbital fractures and possibly concomitant ocular trauma. The ultimate diagnosis is made by computed tomography (CT) of the face.

Diagnostic procedures

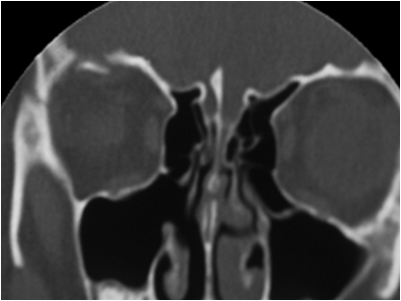

The gold standard for diagnosis of an orbital roof fracture is thin-cut coronal CT scanning of the face/orbits. Contrast is not needed. Although sagittal sections are also helpful in some cases, the axial images are less so. The CT scan will reveal the exact size and location of the fracture as well as associated fractures of the orbit, face and head. Other entities such as foreign bodies, hematoma, globe rupture and optic nerve trauma may also be found. 3D CT reconstruction can be performed, some find this a very helpful modality to define fractures of the orbital rim and frontal bone but generally does not add to the information from other CT images.

Imaging would be indicated to rule out an encephalocele, meningocele, or meningoencephalocele. These may occur even as a delayed presentation in days to weeks after the initial trauma.

Laboratory test

None

Differential diagnosis

It is common for trauma patients to have periorbital ecchymoses and edema without fractures. In addition, poor/blurry vision, blurry vision, double vision and ocular pain are seen in facial trauma without orbital fracture. The differential diagnosis of any orbital fracture should include other orbital floor fractures and traumatic injuries.

Management

General treatment

After a thorough ophthalmic exam and after other trauma has been ruled out, the patient and physician discuss the possible need for surgical intervention.

Medical therapy

In cases of minor isolated orbital roof fractures where no surgical intervention is needed, the patient may require no treatment. The use of oral antibiotics is controversial though some practitioners prescribe them for orbital fractures and some do not. Likewise, some surgeons give oral steroids to help decrease orbital edema and congestion but some do not. In all cases the patient is advised to avoid nose blowing. The patient should not participate in contact sports for 6-8 weeks. Associated ocular trauma must also be addressed and treated appropriately (e.g. antibiotics for corneal abrasion).

Medical follow up

Uncomplicated orbital fractures that do not require surgical intervention are often seen 1-2 weeks after the initial injury and then as needed thereafter. In cases of orbital roof fractures, neuro-surgical follow-up should be per their recommendations.

Surgery

Surgical intervention in the case of isolated orbital roof fractures is uncommon. If signs of muscle entrapment (e.g. levator dysfunction) or bone fragment impingement on other critical structures (e.g. optic nerve) are seen, surgery may be required. Access to the roof may be gained through a superior lid crease approach. In cases of large comminuted and displaced fractures of the roof, surgical intervention often requires a team approach with members of the neurosurgical team and/or members of the otolaryngology department. The approach for these types of fractures is via a coronal flap with craniotomy.

Repair of roof fractures can be complicated. Gravitational forces make it difficult to keep an implant in place from the orbital side of the fracture. Most implants must be placed from the frontal sinus/cranial side of the fracture making access difficult. Implant material is similar to that used with other orbital wall fractures While the gold standard is calvarial bone graft, alloplastic material can also be utilized (e.g. titanium, PPE, nylon foil).

A comprehensive review of the literature published in 2020 encompassed 526 orbital roof patients from 47 studies (Lucas et al). Most common etiologies for roof fracture were motor vehicle accidents (39.5%), falls (30.3%), and assault (11.8%). Sixty percent of patients underwent surgical repair, while 40% were managed conservatively. The bicoronal approach was used the large majority of the time (94.8%), and titanium miniplates were the most common implant used (46.2%). Patients undergoing surgery were adults with clinical symptoms including exophthalmos, diplopia, and gaze restriction as well as patients with dura exposure. Most patients undergoing surgery were those with concomitant fractures. Pediatric patients were more likely to be treated conservatively.

Surgical follow up

In the immediate post operative period, the patient is reminded to avoid nose blowing and strenuous exercise. The patient is seen at one week and at some time thereafter depending on how the recovery goes. Patients are reminded that because of edema, hematoma, damage to the muscles and nerves of the orbit, and boney fusion, the ultimate post operative healing outcome may not occur for months. Patience is a virtue.

Complications

Complication of the surgery are directly related to the severity of the orbital fracture. Common complications are postoperative edema, chemosis, ecchymoses, blurry vision, discomfort and tenderness. Double vision may persist even after release of entrapment secondary to extraocular muscle and nerve damage. Dislodgement of an implant may occur and optic nerve damage is possible. In cases of frontal sinus involvement, the patient may need to be followed for possible frontal sinus mucocoele. If intracranial communication with the orbit and/or sinus is present, meningitis or encephalitis my occur. Meningoencephalocele or encephalocele may be a late complication of large unrepaired roof fractures. These often present with pulsatile proptosis and hypoglobus.

Prognosis

Prognosis is directly related to the severity of the roof fracture. In cases of isolated non-displaced roof fractures, the prognosis is excellent. If the roof fracture is large, comminuted and severely displaced, the prognosis is less promising.

Additional Resources

- Boyd K, Rizzuto PR. What Is an Orbital Fracture? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart® Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/orbital-fracture. Accessed July 22, 2024.

References

- Santamaria J, Mehta A, Reed D, et al. Orbital roof fractures as an indicator for concomitant ocular injury. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019 Nov;257(11):2541-2545.

- Connon FV, Austin SJ, Nastri AL. Orbital Roof Fractures: A Clinically Based Classification and Treatment Algorithm. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015 Sep;8(3):198-204. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393728.

- Karabekir HS, Gocmen-Mas N, Emel E, et al. Ocular and periocular injuries associated with an isolated orbital fracture depending on a blunt cranial trauma: anatomical and surgical aspects. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012 Oct;40(7):e189-93.

- Thurston TTE, Jackson AS, Nazir N, et al. Risk assessment of isolated single-wall orbit fractures and eye injury. J Craniofac Surg. 2018 Jun;29(4):943-945.

- Kim YJ, Ahn S, Seo DW, et al. Patterns and injuries associated with orbital wall fractures in elderly patients who visited the emergency room: a retrospective case-control study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6(9):e011110.

- Ha AY, Mangham W, Frommer SA, et al. Interdisciplinary management of minimally displaced orbital roof fractures: delayed pulsatile exophthalmos and orbital encephalocele. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2017 Mar;10(1):11-15.

- Lucas JP, Allen M, Nguyen BK, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Carron M. Orbital Roof Fractures: An Evidence-Based Approach. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020 Aug 10.