Orbital Emphysema

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Orbital Emphysema (OE) does not have a specific ICD-10 code but can fall under other disorders of the orbit, H05.09.

Orbital Emphysema

Orbital emphysema (OE) is a generally benign and relatively uncommon condition that results from an abnormal accumulation of air within the orbit or eyelid. OE most commonly occurs after trauma or fracture of the orbital bones; however, case reports throughout the literature have described a wide range of causes, varying from postoperative complications to even nose blowing.

Etiology[1][2]

- Orbital fractures (most commonly of the medial orbital wall)

- Periorbital soft tissue injury

- Weightlifting

- Infection

- Nose blowing, sneezing, coughing

- Iatrogenic

- Compressed-air injury

- Pulmonary barotrauma

- Esophageal Rupture

- Spontaneous

- Factitious Disorders

Risk Factors

Doing or undergoing any of the previously listed activities can increase one's risk for OE.

Pathophysiology

In general, orbital emphysema occurs when air enters the orbit but can not exit, leading to trapping and build up of air.[3] The trapped air can subsequently lead to complications from increased intraorbital pressure such as central retinal artery occlusion (CRVO) and compressive optic neuropathy. Specific mechanisms based on etiology of OE will be discussed below.

Mechanisms based on etiology:

- Trauma to the orbit from direct blows, vehicle accidents, etc, leading to orbital wall fractures, is the most common cause of orbital emphysema. The fractured orbital wall and damaged sinus and adjacent tissue create a pathway allowing air from the paranasal sinuses to enter the orbit. Post-trauma nose blowing, sneezing, or coughing produces increased intranasal pressure, exacerbating air escaping into the orbit. Additionally, orbital tissue that has been disrupted such as damaged fatty tissue, can block the air from exiting the orbit, thus acting as a one-way-valve.[4] OE, when present clinically, has a high specificity of 99.6% and a positive predictive value of 98.4% for an orbital fracture.[5]

- Lacerations to nearby soft tissue (e.g. eyelid or conjunctiva) can also introduce air directly into the orbit.

- Increased sinus or upper respiratory tract pressure can lead to spontaneous fracture or dehiscence of the lamina papyracea. This can occur due to nose blowing or sneezing (with no history of trauma) or due to the Valsalva maneuver that occurs while weightlifting.

- Weak points allowing for air entry into the orbit can also be caused by neoplasms such as ethmoidal and frontal osteomas.

- Barotrauma can lead to spontaneous dehiscence of the lamina papyracea, which occurs due to extreme pressure differentials inside and outside the nasal cavities during activities such as diving. This will allow air to accumulate in the orbit as well

- Procedures that introduce air to the fascial planes such as upper GI endoscopies, facial implant removals, laparoscopic nephrectomy, thoracotomy, and Nissen fundoplication, etc all have the potential to cause OE. Post-procedure air migration throughout the body is facilitated by the connections between deep fascial planes in the face, neck, and chest.

- Direct iatrogenic introduction of air into orbit can occur during or after surgical procedures such as functional endoscopic sinus surgery, maxillary sinus floor elevation procedures, orbital decompression for thyroid eye disease, balloon dacryoplasty, etc.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis

Diagnosis of orbital emphysema is made by history taking and physical examination. Imaging of the orbit can also be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

History

While orbital emphysema presents variably at differing levels of severity, patients usually report a pressure sensation or pain with an accompanying change in visual acuity or field.[2] It is also important to take a good history as it will often provide the potential cause and mechanism for their OE.

Signs

- Periorbital subcutaneous crepitus

- Proptosis

- Subconjunctival emphysema

- Vertical globe dystopia as free air tends to accumulate superiorly in the orbit[6]

- Restriction of eye movement

- Decreased visual acuity

- Relative afferent pupillary defect

Symptoms

- Pressure Sensation

- Pain

- Change in visual acuity/field

- Diplopia

- Limitations of directional gaze[7][8]

Physical Examination

Palpation of the eyelid and orbit can be performed to look for a crackling sensation or noise, which is pathognomonic for emphysema.

Diagnostic procedures

Imaging will confirm the presence of air and may help visualize and characterize the underlying etiology of OE such as a possible bony injury.

Useful imaging modalities include:

Plain radiographs: X-rays may reveal air within the orbital cavity. This modality has a high false negative rate of 50% and may not detect small amounts of air or subtle fractures.[9] Additionally, vertical globe dystopia is a physical exam finding, which can look like a crescent-shaped area of radiolucency in the superior aspect of the orbit on a radiograph (see Figure 1). This finding is also termed the “black eyebrow sign”[6][10][11].

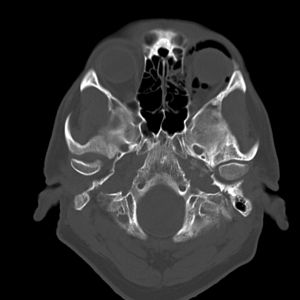

Computed Tomography: This scan is the most definitive imaging modality for diagnosing OE and helps identify the presence, location, and volume of air in the orbit (see Figure 2). It can also confirm the presence of bony defects, provide information about the optic nerve, and help visualize extraocular muscles as well for entrapment.

Laboratory test

Additional tests such as CBC, CRP, ESR, and cultures may be warranted to rule out underlying conditions or complications, but are not necessary for diagnosis of OE.

Differential diagnosis

- Infection with gas-producing organisms

- Orbital foreign bodies (wood/polystyrene)

- Occult Malignancy

Management

General treatment[2]

Most cases of OE will resolve spontaneously without treatment or surgical intervention. It is recommended to avoid coughing, sneezing, nose blowing, or performing valsalva maneuvers while healing. Often digital compression can allow for expulsion of air when there is a preexisting traumatic or iatrogenic opening into the sinus cavity. In moderate cases, particularly if there is concern for compressive optic neuropathy, needle decompression with or without lateral canthotomy and cantholysis should be performed. If there is significant OE with decreased vision and an RAPD, orbital decompression surgery is indicated to relieve pressure and preserve vision. Rarely, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is used to treat OE.

Medical therapy

Analgesics for pain management, and prophylactic oral antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent secondary infections.[1][17][18]

Additional medical therapy may be indicated to manage secondary complications of OE, such as administering IV methylprednisolone to treat compressive optic neuropathy.[2]

Surgical follow up

Additional procedures may be indicated to treat underlying causes, such as surgically closing sino-orbital fistulas that may have caused OE originally.[2]

Prognosis

In most cases of OE, there is spontaneous resolution of symptoms within 7-10 days without any lasting consequences.[2] Those who received needle decompression with or without lateral canthotomy and cantholysis tended to have decreased visual acuity. Patients who underwent orbital decompression were more likely to have signs of optic nerve compression such as RAPD and decreased visual acuity as well.[2]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Zimmer-Galler IE, Bartley GB. Orbital emphysema: case reports and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69(2):115-121. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61036-2

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Roelofs KA, Starks V, Yoon MK. Orbital Emphysema: A Case Report and Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;35(1):1-6. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001216

- ↑ van Issum C, Courvoisier DS, Scolozzi P. Posttraumatic orbital emphysema: incidence, topographic classification and possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. A retrospective study of 137 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115(6):737-742. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2012.10.021

- ↑ Moon H, Kim Y, Wi JM, Chi M. Morphological characteristics and clinical manifestations of orbital emphysema caused by isolated medial orbital wall fractures. Eye (Lond). 2016;30(4):582-587. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.285

- ↑ Büttner M, Schlittler FL, Michel C, Exadaktylos AK, Iizuka T. Is a black eye a useful sign of facial fractures in patients with minor head injuries? A retrospective analysis in a level I trauma centre over 10 years. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(6):518-522. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.03.018

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Hatton MP, Rubin PA. Management of orbital compartment syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(3):433-434. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.3.433-b

- ↑ Burt B, Jamieson M, Sloan B. Medial wall fracture- induced pneumo-orbita mimicking inferior rectus entrapment. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(1):119.e1-119.e1193. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2009.04.040

- ↑ Collin J, Afshar F, Thomas S. Medial Wall Fracture and Orbital Emphysema Mimicking Inferior Rectus Entrapment in a Child. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2015;8(4):345-347. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1399802

- ↑ Gauguet JM, Lindquist PA, Shaffer K. Orbital Emphysema Following Ocular Trauma and Sneezing. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;3(1):124. Published 2015 Nov 6. doi:10.2484/rcr.v3i1.124

- ↑ Feyaerts F, Hermans R. The black eyebrow sign in orbital blowout fracture. JBR-BTR. 2009;92(5):251-252.

- ↑ Sawicki WK, Hunter G. Eyebrow sign in facial trauma. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2011;28(11):962-962. doi:10.1136/emj.2010.110403

- ↑ Cheema RA, Lukaris AD, Lane CM. Orbital cellulitis with gas. Orbit. 2000;19(1):41-44.

- ↑ Knezevic M, Rasic D, Stojkovic M, Jovanovic M, Bozic M. Acute post-surgical bilateral orbital gas-producing infection — a case report and literature review. Graefe’s archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. 2012;250(9):1403-1406. doi:10.1007/s00417-012-2047-z

- ↑ Joos ZP, Longenecker LG, Patel BC. Orbital foreign body masquerading as orbital air. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2016;44(7):637-639. doi:10.1111/ceo.12741

- ↑ Ho V, McGuckin J, Smergel E. Intraorbital wooden foreign body: CT and MR appearance. American journal of neuroradiology : AJNR. 1996;17(1):134-136.

- ↑ Roberts CF, Leehey PJ 3rd. Intraorbital wood foreign body mimicking air at CT. Radiology. 1992;185(2):507-508. doi:10.1148/radiology.185.2.1410363

- ↑ Ababneh O. H. (2013). Orbital, subconjunctival, and subcutaneous emphysema after an orbital floor fracture. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.), 7, 1077–1079. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S44649

- ↑ Bagheri, A., Veisi, A., Memarzade, S. E., & Tavakoli, M. (2018). Orbital, Periorbital, and Intracranial Emphysema Caused by Compressed Air Injury in a 5-Year-Old Child. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery, 34(5), e151–e153. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0000000000001165