Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia: Ocular Features

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia(MEN): Ocular features

This article describes Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia(MEN) as a group of hereditary tumour syndromes and how they pertain to ocular features, particularly in cases of MEN type2B.

Disease Entity

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome, ICD-10 code: E31.20.

Disease and Classification

Multiple endocrine neoplasia(MEN) comprises a group of rare genetic disorders characterized by the increased risk of developing neoplasias in two or more endocrine glands.[2][3] MEN can be classified into four major forms: MEN type 1, MEN type 2A, MEN type 2B (also known as MEN3) and MEN type 4. Each type demonstrates a distinct genetic disorder that predisposes an individual to develop specific endocrine neoplasias.[3][4][5] Ocular features and manifestations of MEN are classsically described in MEN type 2, particularly MEN type 2B (MEN2B).[3][5] Tumors of the pituitary gland in MEN1 may cause visual field defects.[6][7]

Epidemiology

MEN1 is the most common of all the MEN syndromes with estimated prevalence of 2-20 per 100,000 in the general population.[6] The prevalence of MEN2 cases is approximately 1 per 35,000.[8] The epidemiology of MEN2B is unknown.[8]

Etiology

MEN syndromes demonstrate an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with high penetrance and variable expressivity.[3][5] MEN1 is caused by mutations to the tumour-suppressor gene MEN1 which codes for a protein Menin. The MEN1 gene is lacated at chromosome 11q13.[6][7] Most MEN2 patients have a mutation of the RET (rearranged during transfection) proto-oncogene. This gene is localized to Chromosome 10 (10q11.2).[6]

Risk Factors

Individuals with RET mutations in MEN2 have 50% risk of genetic transmission to their offspring due to autosomal dominant inheritance.[7]Somatic mutations of the RET proto-oncogene have also been identified.[6]

Pathophysiology

The development of MEN1 requires two genetic hits of both allelic copies of the MEN1 tumour-suppressor gene resulting in a loss of its function which can then lead to unregulated cellular growth.[7] The first mutation is inherited in a germ-line fashion. Menin is expressed in both endocrine and non-endocrine tissues.[7]The exact oncogenic mechanism of how the protein Menin is involved in MEN1 is unknown.[9]

In MEN2, the RET proto-oncogene encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor protein that plays a role in the differentiation and migration of developing neuro-endocrine tissues.[7] Missense mutations in this RET gene results in a single amino acid alteration which leads to a gain of function of this protein.[7] A mutation at the substrate recognition pocket at codon 918 is present in 95% of patients with MEN2B.[6]

A correlation exists between the specific RET mutation and the clinical phenotype of an affected patient with medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) in MEN2. Patients with MEN2B expressing M918T mutations of the RET gene often present with disease in infancy and have the most aggressive form of MTC.[7]

RET is expressed in multiple tissues which include: thyroid parafollicular cells (C cells), parathyroid glands, enteric ganglia, adrenal chromaffin cells and both peripheral- and central-neurons. This explains the variable neoplastic patterns in patients with MEN2.[7]

General Pathology

MEN1 includes tumors of the parathyroid gland, pituitary gland and gastro-entero-pancreatic tract.[6] Pituitary tumors are found in 20%-30% of patients with MEN1.[6] Prolactinomas form the most common pituitary gland tumur in MEN1.[9] Pituitary tumors may result in chiasmal syndrome due to compression of the optic chiasm.[10]

MEN2A and MEN2B are associated with MTC and pheochromocytoma.[6]

MEN2A is the combination of MTC, pheochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism. Familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (FMTC), MEN2A with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis and MEN2A with Hirschprung disease form the three sub variants of MEN2A.[6]

MEN2B is typified by the association of MTC, pheochromocytoma, mucosal neuromas and intestinal ganglioneuromatosis.[6]

MTC arises from C cells and comprises 3% to 9% of all thyroid cancers.[7] MTC is hereditary in 25% of cases, occurring in almost all patients with MEN2 syndromes.[7] MTC is sporadic in 75% of cases.[7] MTC in MEN2B develops earlier and behaves more aggressively than in MEN2A.[6][7]

Pheochromocytoma develops in 40%-50% of patients with MEN2B.[7]Pheochromocytoma in MEN2 is almost always benign and confined to the adrenal medulla.[7]

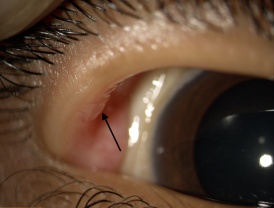

Hyperparathyriodism does not develop in MEN2B.[7] Unencapsulated thickened proliferation of nerves form mucosal neuromas found in the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa and conjunctiva. Intestinal ganglioneuromas of the myenteric plexus develop in MEN2B and may also develop a megacolon.[7]

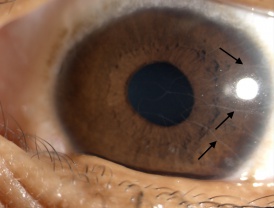

Eyelid and conjunctival neuromas and prominent thickened corneal nerves are distinctive ophthalmic findings in MEN2B.[11] Histopathologic examination of these thickened corneal nerves show nonmyelinated nerves associated with Schwann cells with normal appearing axons that vary in diameter between 0.1ng and 1.4ng.[11]

Diagnosis

Clinical History

A family history of a patient may reveal a relative family member treated for MEN due to the autosomal dominant nature of the disease.[3][5] Patients with MEN syndrome often present in a clinically heterogenous manner. The diagnosis of MEN syndromes are typically based on a known family history of the disease and non-ophthalmic findings. A detailed ocular examination may direct the work-up and differential diagnosis, especially in new cases of MEN.[9]

Symptoms

Patients with pituitary tumors in MEN1 may complain of worsening visual acuity, diplopia and even chromatic alterations.[10] Ocular symptoms of dry eyes may be found in patients with MEN2B.[3] Hormone excess in MEN may cause certain symptoms, depending on the involved hormone.[6] A disproportionate increase in epinephrine relative to norepinephrine in pheochromocytoma may lead to symptoms of palpitations, anxiety or headaches.[6] Children with MEN2B most commonly present with gastrointestinal symptoms.[6] Patients may also complain of a palpable thyroid mass associated with dysphagia or hoarseness in cases of established MTC.[7]

Physical examination

A thorough physical examination combined with a slit-lamp examination of the eye and ocular adnexal structures is required to identify phenotypic signs of MEN2B. Distinctive features of MEN2B is often recognizable in childhood.[6]

Signs

Typical ocular features in MEN2B:[3][5][12][13]

- Prominent corneal nerves (most commonly)(See Figure 1)

- Conjunctival and eyelid neuromas(See Figure 2)

- Dry eye disease

- Thickened eye lids

- Open angle glaucoma (rarely)

Non-ocular features in MEN2B:[3][14][13]

- Hypertrophic lips.

- Marfanoid body habitus.

- Mucosal neuromas.

- Intestinal ganglioneuromas.

Clinical diagnosis

MEN2B should be ruled out in any patient with prominent corneal nerves, especially if there are additional suggesting ocular and systemic features present.[15]

Diagnostic investigations

Goldman Visual field (GVF) perimetry can be used to confirm visual field defects in cases of suspected chiasmal syndrome caused by pituitary tumors in MEN1. These visual field defects typically respect the vertical meridian. Bitemporal hemianopia is the most frequent visual field defect. Perimetry provides the most effective follow-up study for the detection of visual impairment.[10]

Neuro-imaging in the form of computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to confirm the presence of a suspected pituitary macro-adenoma in cases of MEN1.[10]

Ishihara test may be affected in patients with pituitary tumors.[10]

Basal hormone-levels and dynamic hormone measurements can be done depending on the suspected endocrine tumor.[10] Prolactin levels can identify prolactin-secreting tumors of the pituitary gland. Calcitonin levels can be used as a tumor marker in the treatment of patients with MEN2.[6][7]Clinical screening for pheochromocytomas is done with measurement of metanephrine levels in plasma or 24-hour urine sample. Adrenal CT or MRI is done in positive or borderline cases.[7]

High-resolution optical coherence tomography (HR-OCT) provides a noninvasive correlation to histopathologic findings in conjunctival neuromas and can be used to differentiate mucosal neuromas from other entities.[12] Biopsy may provide histopathologic conformation of a mucosal neuroma.

Differential diagnosis

Though prominent corneal nerves present in the majority on MEN2B patients, they are not specific. Corneal nerves may also be observed in other conditions but are usually described as less prominent.[3]

Corneal nerves may also be observed in the following conditions:[3][16][15]

- MEN type2A

- Refsum syndrome

- Hansen disease

- Riley-Day syndrome

- Neurofibromatosis

- Congenital ichthyosis

Certain corneal conditions such as keratoconus, herpes simplex keratitis and posterior polymorphous dystrophy may also have corneal nerves which are more visible.[3][15][16]

Patients with pure mucosal neuroma syndrome (MNS) may present with similar ocular features as in cases with MEN2B.[3]

Management

An integrated multi-disciplinary approach should be adopted in the management of a patient with MEN. This is accomplished with the involvement of a clinical geneticist, endocrinologist, surgeon and oncologist. The treatment and management of MEN syndromes is beyond the scope of this article and should be based on a case-to-case basis.

The ophthalmologist plays an important role in assisting with the timely diagnosis, referral and visual rehabilitation in patients with ocular manifestations or visual complaints in MEN.

Screening

Genetic counselling is essential and should ideally be done prior to genetic screening of patients at-risk of MEN2. Sequencing of the RET gene has become the standard screening test for all patients with suspected MEN2.[7] Screening should occur at birth or as early as possible in families affected by MEN2. The early genetic screening and diagnosis is important since clinical screening and preventative surgery is determined by the patient’s carrier status of their germ-line RET mutation.[7] All first-degree relatives of a newly diagnosed RET mutation index case should be offered genetic counselling. A known identified RET mutation can be used to limit the sequencing to the known location of the mutation in fellow family members. Family members are at the same risk for MEN2 as the general public if tested negative for their kindred’s known mutation.[7]

Prevention

Early preventative surgery includes a total thyroidectomy and central lymph node dissection during the first few months of life in patients with germ-line mutations of codons 883, 918 and 922 in MEN2B.[6] This is due to the lifetime penetrance of MTC that is nearly 100% in carriers of these RET mutations.[7]

Prognosis

Patients with MEN2B develop MTC in the first and second decades of life.[17] Patient age at presentation and tumor stage are independent predictors of survival since recurrent MTC is the major cause for morbidity and mortality in patients with MEN2B.[17] Lethal outcomes may be prevented by the early diagnosis and treatment of a patient with suspected MEN2B.[6]

Additional Resources

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2

- Patient quality of life and prognosis in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndromes. https://www.aao.org/image/multiple-endocrine-neoplasia-syndromes Accessed February 16, 2023.

- ↑ Grajo JR, Paspulati RM, Sahani DV, Kambadakone A. Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes: a comprehensive imaging review. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016; 54: 441-451.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Lekhanont K, Sontichai V, Bunnapradist P. Prominent corneal nerves, conjunctival neuromas, and dry eye in a patient without MEN2B. Can J Ophthalmol. 2019;54: e313-e317.

- ↑ Thakker RV. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and type 4 (MEN4). Mol Cell Endocrine.2014;386(1-2): 2-5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Kim SK, Dohlman CH. Causes of enlarged corneal nerves. Int Ophthal- mol Clin. 2001;41:13–23.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalos J, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2012: 3072-3078.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, editors. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice, 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:995-1008.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Znaczko A, Donnelly DE, Morrison PJ. Epidemiology, clinical features, and genetics of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B in a complete population. Oncologist. 2014;19(12):1284–1286. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0277

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Kamboj A, Lause M, Kumar P. Ophthalmic manifestations of endocrine disorders-endocrinology and the eye. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6(4):286–299. doi:10.21037/tp.2017.09.13

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Astorga-Carballo A, Serna-Ojeda JC, Camargo-Suarez MF. Chiasmal syndrome: Clinical characteristics in patients attending an ophthalmological center. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2017;31(4):229–233. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2017.08.004

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Riley FC Jr, Robertson DM. Ocular histopathology in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2b. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981; 91(1):57-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(81)90349-4

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Chang TC, Okafor KC, Cavuoto KM, Dubovy SR, Karp CL. Pediatric Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B: Clinicopathological Correlation of Perilimbal Mucosal Neuromas and Treatment of Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2018;4(3):196–198. doi:10.1159/000484053

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Jacobs JM, Hawes MJ. From eyelid bumps to thyroid lumps: report of a MEN type IIb family and review of the literature. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17:195–201.

- ↑ Walls GV. Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:96–101.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Eter N, Klingmüller D, Höppner W, Spitznas M. Typical ocular findings in a patient with multiple endocrine type 2b syndrome. Graefes Arch Clin EXP Ophthalmol. 2001;239(5):391-394.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Dennehy PJ, Feldman GL, Kambouris M, O’Malley ER, Sanders CY, Jackson CE. Relationship of familial prominent corneal nerves and lesions of the tongue resembling neuromas to multiple endocrine neo- plasia type 2B. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:456–61.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Hughes MS, Feliberti E, Perry RR, et al. Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2A (including Familial Medullary Carcinoma) and Type 2B. [Updated 2017 Oct 8]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481898/