Metastasis to the Extraocular Muscles

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Malignancy neoplasm of the extraocular muscles (ICD-10 # C69.6 - Malignant neoplasm of orbit)

Disease

Metastatic seeding of tumor cells to the orbit is rare. It is seen in 2 to 4.7% of all cancer patients and accounts for 4 to 14.7% of all orbital tumors.[1] Among a series of 227 patients who died of malignancy, 28 were found to have orbital involvement.[2] Among orbital metastases, isolated seeding of the extraocular muscles (EOM) is exceedingly rare and accounts for 5 to 9% of cases.[1][3] Metastasis to the EOM occurs in advanced systemic malignancy and is associated with poor outcomes.

Risk Factors

Although seen in few cases, numerous malignancies including breast, lung, skin, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tumors have the potential to metastasize to the orbit. Typically, the diagnosis of the primary tumor is known at the time of presentation; however, ocular symptoms related to EOM metastasis may be the presenting symptom of an undiagnosed distant malignancy.[4][5] The most common primary sources of EOM metastasis are breast adenocarcinoma, cutaneous melanoma, gastrointestinal carcinoma, and lung carcinoma.[4] Other primary malignancies that have been reported to metastasize to the EOM include renal cell carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, prostate carcinoma, thyroid malignancy, gastrointestinal carcinoid, cutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and gestational choriocarcinoma.[1][4][6]

General Pathology

Metastatic EOM lesions are more commonly unilateral with bilateral involvement seen in approximately one-third of patients..[1] The most commonly involved muscles are the lateral rectus and medical rectus. Lesions are rarely seen in the oblique muscles, and no cases have been reported of isolated oblique muscle lesions without involvement of at least one rectus muscle.[1][4] Imaging usually reveals isolated enlargement of affected muscles, but it may also demonstrate nodular lesions.[1][7] In unclear cases, fine-needle aspiration biopsy may be performed, although this is not required for diagnosis.[8] Histopathologic characteristics will differ in EOM metastases depending on the primary tumor. In some cases, the histologic features of orbital metastasis may differ from those of the primary tumor.[7]

Pathophysiology

These lesions are hypothesized to reach the orbit through hematogenous seeding of advanced systemic malignancy.[7] The exact pathogenesis and the preference of the EOM tumor microenvironment is still poorly understood, but metastasis to the orbit and EOMs is associated with aggressive primary cancer.

Primary Prevention

Early detection and treatment of primary malignancy may prevent EOM metastasis. Regular screening for breast and skin cancer likely has the greatest impact as these are the most common primary malignancies to metastasize to the EOM.

Diagnosis

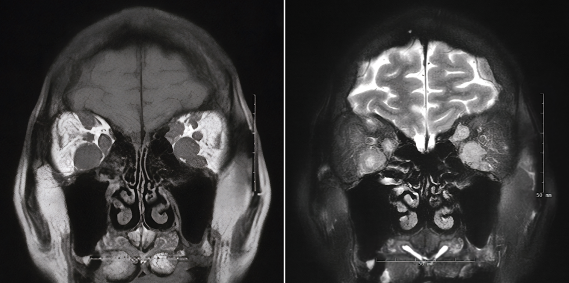

EOM metastasis may not be apparent on initial ocular examination. The diagnosis is suggested by clinical history and confirmed with imaging, which may include computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasound.[8]

History

The average age of patients with EOM metastasis is 53 years, which is lower than that of general orbital metastasis at 62-73 years. There is no gender predominance and no preference for the right or left eye.[1][9] The time course of symptoms varies depending on the primary tumor site. For the most common sites of skin and breast, ocular symptoms appear an average of 2 and 3 years after the initial cancer diagnosis, respectively.[4] Reported averages for the onset of ocular symptoms across all primary malignancies is 30 months.[1]

Physical Examination

A complete bilateral eye exam should be performed in any patient suspected of having EOM metastasis. A thorough assessment of external structures and ocular motility are particularly important. Anterior and posterior segment examination is typically normal, as are intraocular pressure measurements.[1]

Signs

- Proptosis

- Enophthalmos

- Restricted eye movement

- Ptosis

- Chemosis

- Conjunctival injection

- Eyelid swelling

- Eyelid retraction

Symptoms

- Pain

- Diplopia

- Epiphora

- Reduced visual acuity

Clinical Diagnosis

EOM metastasis should be suspected in a patient with days to weeks of unilateral or bilateral eye pain, diplopia, proptosis, or restricted eye movement with a normal anterior and posterior segment exam. Known history of systemic malignancy should increase clinical suspicion for the diagnosis.

Diagnostic procedures

CT or MRI of the orbits are the most frequently used diagnostic imaging studies. Although less commonly used, ultrasound (A-scan or B-scan) has been equally successful in detecting lesions.[1] A minority of patients undergo biopsy for confirmation of the diagnosis, but fine needle aspiration may be performed after imaging is obtained.

Differential diagnosis

Thyroid eye disease (TED)

TED is an autoimmune condition that affects approximately 25% of patients with Grave’s disease [hyperthyroidism].[10] However, patients with euthyroid and hypothyroid status may also be affected. TED is likely caused by activation of orbital fibroblasts by auto-antibodies that bind to the TSH receptor on the surface of those cells.[10] This results in enlargement of EOMs, orbital fat and connective tissue, with characteristic lid retraction, proptosis, double vision, and eye discomfort. While patients with TED have similar physical exam findings such as changes in mass of EOMs and visual changes, the presence of other clinical findings associated with TED can help differentiate it from EOM metastasis.

Nonspecific orbital inflammation (NSOI)

NSOI is an important diagnosis of exclusion when assessing for EOM metastasis. NSOI is a spectrum of primary orbital inflammatory diseases without clear etiology, which doesn’t arise from any infectious, neoplastic or immunologic processes.[11] Inflammation can affect any structure of the orbit, including the myositic components.[12] The hallmark symptom of NSOI is pain at the site of ocular inflammation, which can be helpful in distinguishing it from EOM metastasis, which can present with variable levels of pain and discomfort.[11][12]

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease wherein noncaseating granulomas form in at least two organ systems, most commonly the lungs, mediastinal lymphatic system, skin and eyes.[13] Ophthalmologic involvement is present in 20-50% of cases, most typically as a granulomatous uveitis associated with venous retinal vasculitis and lesions of peripheral multifocal choroiditis.[13] However, ophthalmic involvement of sarcoidosis can result in episcleritis and/or scleritis, eyelid abnormalities, conjunctival granulomas, optic neuropathy, lacrimal gland enlargement, and orbital inflammation.[14] Therefore, ophthalmic involvement of sarcoidosis can result in the enlargement of EOMs in select patients and must be considered in the differential of EOM metastasis.

Orbital Lymphoma

Orbital lymphomas represent 50-60% of ocular adnexal lymphomas, which commonly involve EOM and present with exophthalmos. Orbital lymphomas are a sub-set of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), representing 8-10% cases of extra nodal NHL, that originate and involves the lacrimal gland(s), soft tissues of the eyelid, conjunctiva and EOM.[15] Given that orbital lymphomas are a primary neoplastic process, it is important to consider orbital lymphoma in the differential of EOM metastasis and differentiate whether the patient has a primary or secondary neoplastic condition.

Carotid cavernous fistula (CCF)

CCF is an abnormal vascular connection between the arteries and veins that arise within the cavernous sinus, which are classified according to etiology of either traumatic or spontaneous. Imaging findings of CCF typically demonstrate EOM enlargement with enlargement of cavernous sinus and ophthalmic veins.[16] Symptoms of CCF present in a similarly non-specific manner as EOM metastasis, including double vision, headache and proptosis. Additionally, physical exam typically includes presence of pulsatile exophthalmos, orbital bruit, chemosis, pulsatile tinnitus, and conjunctival arterialization, which may help to differentiate it from classic presentation of EOM metastasis.[17]

Management

General treatment

Orbital metastases are intrinsically associated with poor survival due to occurrence in advanced disease.[8] Lesions within the EOMs are ominous signs of disease burden and are associated with poor clinical outcomes. There is no standardized treatment approach, with radiotherapy, chemotherapy or surgical debulking, or a combination of the three, serving as the major therapeutic options provided to patients, based on disease burden and patients’ treatment goals.[1] Therefore, the goal of treatment is palliative, with external-beam radiotherapy being the preferred treatment option, given that various primary tumors are extremely sensitive to radiation.[1] In some cases, chemotherapy can serve as a second-line therapeutic. The extent of metastatic EOM seeding along with patient preference, however, should also be considered.

Medical therapy

Based on available data, a minority of patients pursue chemotherapy to improve ocular symptoms.[1] Frequently cited chemotherapeutic agents that aim to treat the intraorbital component of the disease include etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin-D, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, and vincristine.[18][19] Detailed outcomes are not available, and likely vary based on primary tumor and its scale and grade.[19]

Several case reports have also included the use of radiation therapy for EOM metastasis, including patients with primary vulvar melanoma, carcinoid tumor, breast carcinoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma.[19][20][21][22]

Monitoring of response to chemotherapy and radiotherapy typically utilizes positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the EOMs.[23]

Surgery

Surgical tumor debulking is rarely performed but may improve symptoms.[1]

Complications

Detailed outcomes of surgical debulking are not available in the literature, but potential complications include those associated with any orbital surgery, including infection, worsening diplopia, and diminished visual acuity.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Leung V, Wei M, Roberts TV. Metastasis to the extraocular muscles: a case report, literature review and pooled data analysis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(6):687-694. doi:10.1111/ceo.13162

- ↑ Font RL, Ferry AP. Carcinoma metastatic to the eye and orbit III. A clinicopathologic study of 28 cases metastatic to the orbit. Cancer. 1976;38(3):1326-1335. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197609)38:3<1326::aid-cncr2820380336>3.0.co;2-#

- ↑ Shields JA, Shields CL, Brotman HK, Carvalho C, Perez N, Eagle RC Jr. Cancer metastatic to the orbit: the 2000 Robert M. Curts Lecture. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17(5):346-354. doi:10.1097/00002341-200109000-00009

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Lacey B, Chang W, Rootman J. Nonthyroid causes of extraocular muscle disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;44(3):187-213. doi:10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00101-0

- ↑ Foo FY, Lee M, Looi A. Asymptomatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma presenting as an orbital metastatic tumor. Orbit. 2010;29(5):262-265. doi:10.3109/01676830.2010.485719

- ↑ Alsuhaibani AH, Carter KD, Nerad JA, Lee AG. Prostate carcinoma metastasis to extraocular muscles. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(3):233-235. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181706d08

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ahmad SM, Esmaeli B. Metastatic tumors of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18(5):405-413. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282c5077c

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Char DH, Miller T, Kroll S. Orbital metastases: diagnosis and course. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(5):386-390. doi:10.1136/bjo.81.5.386

- ↑ Goldberg RA, Rootman J, Cline RA. Tumors metastatic to the orbit: a changing picture. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;35(1):1-24. doi:10.1016/0039-6257(90)90045-w

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Garrity JA, Bahn RS. Pathogenesis of Graves ophthalmopathy: implications for prediction, prevention, and treatment. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:147–53.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Slagle WS, Boothe KH, Musick AN, Eckermann DR, Slagle AM. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome without pain: a case report. Optometry. 2010;81(3):146-152. doi:10.1016/j.optm.2009.03.021.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Khochtali S, Zayani M, Ksiaa I, et al. Syndrome d’inflammation orbitaire idiopathique : à propos de 24 cas [Idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome: Report of 24 cases]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2018;41(4):333-342. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2017.09.013.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Salah S, Abad S, Monnet D, Brézin AP. Sarcoidosis. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2018;41(10):e451-e467. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2018.10.002.

- ↑ Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):669-683. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.009.

- ↑ Yadav BS, Sharma SC. Orbital lymphoma: role of radiation. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2009;57(2):91-97. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.44516.

- ↑ Jozef Č. Carotid-cavernous fistula from the perspective of an ophthalmologist A Review. Karotído-kavernóza fistula z pohĺadu oftalmológa prehĺad. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2020;1(Ahead of print):1-8. doi:10.31348/2020/8.

- ↑ Jindal G, Miller T, Raghavan P, et al. Imaging evaluation and treatment of vascular lesions at the skull base. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55:151–166.

- ↑ Dhrami-Gavazi E, Lo C, Patel P, Galic V, Pareja F, Kazim M. Gestational choriocarcinoma metastasis to the extraocular muscle: a case report. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(3):e75-e77. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e31829bb2a7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 Yabaş Kızıloğlu Ö, Paksoy Türköz F, Totuk Gedar ÖM, Mestanoğlu M, Yapıcıer Ö. Breast Carcinoma Metastasis to the Medial Rectus Muscle: Case Report. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2019;49(3):168-170. doi:10.4274/tjo.galenos.2018.39018.

- ↑ Pirlamarla AK, Tang J, Amin B, Kabarriti R. Vulvar Melanoma with Isolated Metastasis to the Extraocular Muscles: Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Anticancer Res. 2018;38(6):3763-3766. doi:10.21873/anticanres.12658.

- ↑ Matsuo T, Ichimura K, Tanaka T, Takenaka T, Nakayama T. Neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid) metastatic to orbital extraocular muscle: case report and literature review. Strabismus. 2010;18(4):123-128. doi:10.3109/09273972.2010.525779.

- ↑ Ji SH, Jang JH. Sinonasal Rhabdomyosarcoma Metastasis in Bilateral Multiple Extraocular Muscles: A Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Taehan Yongsang Uihakhoe Chi. 2021;82(1):225-230. doi:10.3348/jksr.2020.0045.

- ↑ Nifosí G, Zuccarello M. Unilateral localized extraocular muscle metastasis by lobular breast carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2018224726. Published 2018 Oct 12. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-224726.