Familial Retinal Arterial Macroaneurysms (FRAM)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Familial Retinal Arterial Macroaneurysms (FRAM), also known as Retinal Arterial Macroaneurysms with Supravalvular Pulmonic Stenosis (RAMSVPS), was first described in 2002.[1] FRAM is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by progressive bilateral multiple retinal arterial macroaneurysms formation and arterial beading along the major retinal arterial trunks with recurrent episodes of hemorrhage and exudation.[1] It is associated with many life-threatening complications due to defective protein formation in smooth muscles of larger vessels.

Etiology

A founder splicing mutation in the Insulin Growth Factor Binding Protein 7 (IGFBP7) gene was found in 30 patients from 15 Saudi families.[2] IGFBP7 was studied and found to be expressed specifically in smooth muscles of the large retinal vasculature but not in the small retinal capillaries which explains the retinal phenotype of FRAM.[3] Histologically multiple linear breaks are seen in the retinal arterial vascular wall which contributes to exudation, hemorrhage and rupture of macroaneurysms.[4] Also, animal studies have shown that Angiotensin II may be an important factor in promoting formation of retinal aneurysms, a crucial factor in retinal aneurysm formation and vessel leakage.[5]

Epidemiology

FRAM has been reported in 30 Saudi patients. Mean age at presentation was 12.5 years (range, 1 – 34 years). Both genders are equally affected.[2]

Diagnosis

History

Patients with FRAM may present with the complaint of decreased vision secondary to hemorrhage and exudation from the macroaneurysm into the macula or might be found incidentally in asymptomatic patients with a family history of FRAM.

Physical Examination

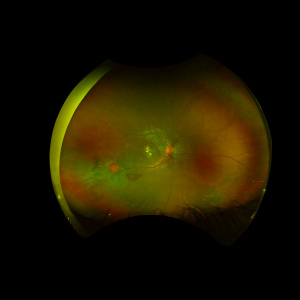

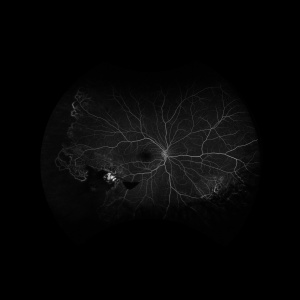

The hallmark of FRAM is macroaneurysm formation and arterial beading in the major trunks of the central retinal artery [Figure 1]. The macroaneurysms, which are typically found in areas of retinal beading, indicate a structural defect in the arterial wall. These macroaneurysms can bleed to the vitreous cavity, sub-hyaloid or sub-internal limiting membrane (ILM) spaces and subretinal space [see Figure 1]. A hyaloid artery remnant can be seen behind the lens or at the optic disc in 88% of FRAM cases.[2] Coat’s disease-like features such as peripheral retinal telangiectatic aneurysmal dilation and peripheral areas of capillary non-perfusion can be seen [see Figure 2]. Leaking aneurysms can lead to intraretinal and subretinal exudate accumulation and, if severe enough, can result in exudative retinal detachment. Areas of retinal vascular sheathing and submacular gliotic mass can be also seen. Episodes of recurrent vitreous, pre-retinal, intra-retinal or subretinal hemorrhage and recurrent exudation secondary to leaking macroaneurysms were reported in 71% of FRAM cases.[2]

Systemic Associations

FRAM is a multisystem disorder associated with cardiac, liver and intracranial manifestations.[2] The majority of FRAM patients who undergo echocardiogram have cardiac defects, most commonly in the form of pulmonary stenosis (valvular or supravalvular) requiring surgical intervention in most of the cases. Liver involvement in the form of cirrhosis has been reported in FRAM patients. Intracranial complications including cerebral hemorrhage and stroke have also been observed among FRAM patients.

Differential diagnosis

- Coat’s disease: in contrast to FRAM, Coat’s disease is idiopathic in nature, unilateral disease affecting young males with no systemic involvement.[6] Coat’s disease is characterized by telangiectatic aneurysmal dilation of the retinal capillaries and does not involve the major retinal arterial trunks.

- Familial parafoveal telangiectasia is characterized by small perifoveal telangiectatic vessels in one or both eyes with no involvement of the major arterial trunks. This condition has been reported to be associated with central nervous system anomalies including cerebral vasculopathy.[7]

- Von Hippel-Lindau is characterized by multiple retinal capillary hemangioblastomas without macroaneurysm formation.[8]

- Idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN) can be confused with FRAM as both entities are characterized by arterial macroaneurysms. However, IRVAN is non-familial and typically presents with vasculitis, anterior chamber cells, and/or mild vitritis.[9]

Management

Management of FRAM depends on the clinical presentation. Retinal grid photocoagulation can be applied to the leaking macroaneurysms to halt lipid exudation or pan retinal photocoagulation in ischemic areas in presence of retinal neovascularization. Vitrectomy can be considered for non-resolving vitreous hemorrhage, and external drainage can be performed for eyes with exudative retinal detachment. Systemic complications like large coronary artery aneurysm have been noted in patients with FRAM. [10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dhindsa HS, Abboud EB. Familial retinal arterial macroaneurysms. Retina. 2002;22(5):607-615. doi:10.1097/00006982-200210000-00012

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Alkuraya H, Patel N, Ibrahim N, et al. Phenotypic delineation of the retinal arterial macroaneurysms with supravalvular pulmonic stenosis syndrome. Clin Genet. 2020;97(3):447-456. doi:10.1111/cge.13676

- ↑ Abu-Safieh L, Abboud EB, Alkuraya H, et al. Mutation of IGFBP7 causes upregulation of BRAF/MEK/ERK pathway and familial retinal arterial macroaneurysms. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(2):313-319. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.010

- ↑ Cahuzac A, Scemama C, Mauget-Faÿsse M, Sahel J-A, Wolff B. Retinal arterial macroaneurysms: Clinical, angiographic, and tomographic description and therapeutic management of a series of 14 cases. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2016;26:36–43.

- ↑ Chen H, Zhao XY, Chen YX, Deng TT. Angiotensin II is a crucial factor in retinal aneurysm formation. Exp Eye Res. 2021 Dec;213:108810. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108810. Epub 2021 Oct 29. PMID: 34757002.

- ↑ Char DH. Coats’ syndrome: Long term follow up. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(1):37-39. doi:10.1136/bjo.84.1.37

- ↑ Grand MG, Kaine J, Fulling K, et al. Cerebroretinal Vasculopathy: A New Hereditary- Syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(5):649-659. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(88)33131-3

- ↑ Haddad NMN, Cavallerano JD, Silva PS. Von hippel-lindau disease: A genetic and clinical review. Semin Ophthalmol. 2013;28(5-6):377-386. doi:10.3109/08820538.2013.825281

- ↑ Chang TS, Aylward GW, Davis JL, et al. Idiopathic Retinal Vasculitis, Aneurysms, and Neuro-retinitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(7):1089-1097. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(95)30907-4

- ↑ Shah MA, Alqahtani A, Alshahrani ST, Alshehri HZ. Giant coronary artery aneurysm associated with familial retinal artery macroaneurysm: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2022 Feb 9;6(2):ytac057.