Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy (mak′yū-lop′ă-thē), initially described as Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy, does not have a designated code as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature, however, it can be classified as a degeneration with the following codes:

ICD- 9

- Peripheral Retinal Degeneration- 362.60

ICD-10

- Degeneration- H35.40

- Degeneration, degenerative- H35.9

Disease

Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy is an uncommon disease of the retinal pigment epithelium that generally affects young adults.[2]It presents as a sudden, severe unilateral central vision loss most commonly following a flulike illness. [3]

Etiology

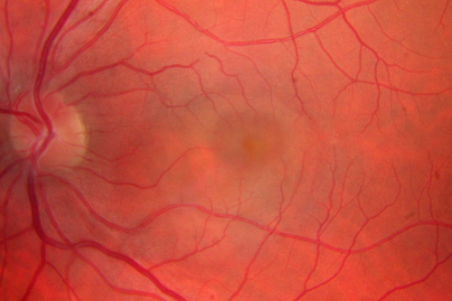

Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy (UAIM) was first described as a syndrome by Yannuzzi, et al in 1991.[3] His report consisted of nine young patients who developed significant unilateral vision loss (20/200 or worse) associated with a characteristic exudative detachment of the macula with grayish thickening of the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Patients experienced spontaneous resolution of their symptoms over the course of several days to weeks with near complete recovery of vision, with a resultant “bulls-eye” macular appearance.[3][4] While his report discussed unilateral vision loss, bilateral cases have also been reported, leading some experts to propose renaming the disease to "Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy (AIM)". [4]

Definition

Maculopathy is a pathologic condition of the macula, which is the centermost part of the retina and is responsible for highly sensitive vision. Medications possibly linked to maculopathy have been found to interfere with the RPE and photoreceptors metabolic functions. AIM is a currently considered a complete separate entity and is not known to be associated directly with an inciting factor.

Epidemiology

AIM by definition is not linked to an underlying disease process or known cause. It notably affects younger Caucasian individuals and it appears to split equally between sexes. A preceding flu-like illness has been reported in several cases and elevated Coxsackie Virus titers were reported in a patient presenting with bilateral disease. [4] . AIM has been described in a 59 year old patient, 30 days after developing with yellow fever disease. [6] Another report has linked AIM after H1N1 vaccination in a 25 year old Caucasian patient. [7] While vision loss at onset is severe and abrupt in nature, spontaneous resolution and recovery of vision is expected.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of AIM is not fully understood, although it is thought to contain an inflammatory component. Initially an irregular neurosensory retinal detachment overlying a smaller, grayish thickening at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium is seen. Some patients have been reported to have a few intraretinal hemorrhages and some may have inflammatory cells in the posterior vitreous.[8]In 1996, Freund, et al. expanded the clinical spectrum of the maculopathy described by Yannuzzi, et al. Their report included an additional 17 patients that presented with new features of this disease. Initially, the it was reported to present unilaterally and possibly associated with a viral prodromal illness. This report demonstrated a bilateral disease course and also showed links to pregnancy. Human immunodeficiency virus has also been implicated.[4] Other findings included papillitis and eccentric macular lesions. The papillitis occurred as both a primary disease and also secondarily, as an extension of the maculopathy, and the four patients presenting with eccentric macular lesions had better visual acuity than typical for AIM owing to the extrafoveal nature of their disease. The intraretinal hemorrhages observed in some acute lesions are thought to be secondary to venous stasis produced by optic nerve inflammation or by concomitant phlebitis. Subretinal exudation was noted in two patients and was thought to represent subretinal inflammatory cells or debris. These findings did not alter the disease course. [8]

Diagnosis

History

Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy classically presents as an abrupt, severe loss in vision (visual acuity 20/200 or worse) in one or both eyes in young, otherwise health individuals. Patients can also report a history of a flulike illness preceding the onset of vision loss. Links to Coxsackie virus have been established,[9] and an association with pregnancy (one case in the first trimester and one four weeks postpartum) has been observed. [8] More recently, possible association between SARS-CoV-2 vaccination as well as infection and AIM were reported.[10][11][12]

Physical Examination

Examination of the posterior pole is achieved through slit-lamp biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy with use of the appropriate lenses.

Signs

Classically, an exudative retinal detachment of the macula is observed on exam. This finding may be unilateral or bilateral. Some patients may also have papillitis or intraretinal hemorrhages as described above.

Symptoms

Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy patients present with a profound painless, central vision loss that is acute in nature.

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis of this disease is clinical and supported by ancillary testing including Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Fluorescein Angiography (FA).

Diagnostic procedures

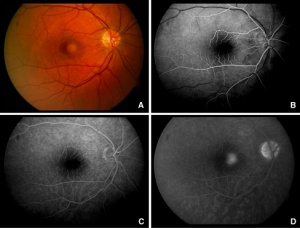

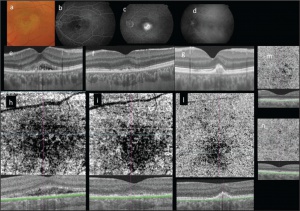

In the acute phase of maculopathy spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) and STRATUSOCT show abnormal heterogeneous hyperreflective thickening at the level of the outer retina and RPE in the foveal region. Hyporeflective exudation and subretinal fluid with detachment and disruption of photoreceptor outer segment can also be seen. [15][16] Swept- Source Optical Coherence Tomography (SS-OCT) demonstrates similar findings. Upon resolution of the disease, the neurosensory detachment often resolves completely, however, patients may develop a focal submacular scar with persistent metamorphopsia. [15] Choroidal neovascular membranes (CNV) can be seen as a complication of AIM.[17]

A case report using Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography demonstrated early irregular hyperfluorescence and hypofluorescence at the level of the retinal pigment epithelial lesion, followed by complete staining of the overlying neurosensory retinal detachment in the late phase of the study. The superficial and deep layers of the retinal capillary plexus were preserved and a dark pattern at the choriocapillaris segmentation line was observed when compared to the right eye.[15]

Indocyanine green angiography shows a hypofluorescent lesion with some hyperfluorescence in the mid-late phase.

Laboratory test

Coxsackie Virus titers may be obtained as these have been elevated in patients at time of diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy includes diseases that present with a focal area of subretinal fluid (SRF) leading to profound central vision loss. Central Serous Retinopathy, Harada Syndrome and APMPEE are included in the differential and can generally be excluded by their FA findings. The possible relationship between AIM and APMPPE has been suggested due to the overlap of many common features including the rapid onset and resolution of symptoms and the following of a prodromal flu-like illness. [3][18] Also, the various macular dystrophies should be considered, however, the progressive loss of vision and pigmentary changes associated with SRF can help distinguish them from AIM.

Management

Historically, AIM has been misdiagnosed and interventions such as photodynamic therapy, systemic corticosteroids and intravitreal triamcinolone have been prescribed.[18] No treatment has been proven to work; it is a self-limiting condition. Patients presumed to have AIM should be observed clinically and with ancillary testing for spontaneous resolution. Viral serology may be obtained to identify an underlying cause.

Medical therapy

No medical therapy is indicated as the maculopathy resolves on its own over the course of several days to weeks.

Medical follow up

Patients should be followed with serial fundus examination and OCT until resolution has occurred.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis for this disease is favorable as most patients achieve full visual recovery upon resolution of the maculopathy.

References

- ↑ "Unilateral Acute Idopathic Maculopathy." Unilateral Acute Idopathic Maculopathy. https://retinavitreous.com/diseases/aim.php Retina Vitreous Associates of Florida, n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ Fuente, Miguel A. De La, and Rubén Cuadrado. "Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy: Angiography, Optical Coherence Tomography and Microperimetry Findings." Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection. Springer-Verlag, 24 Nov. 2010. Web. 26 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Yannuzzi LA, Jampol LM, Rabb MF, Sorenson JA, Beyrer C, Wilcox LM., Jr Unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:1411–1416. [PubMed]

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ghazi,Nicola G., MD, Armand Daccache, MD, and Brian P. Conway, MD. "Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy." AAO Journal. American Academy Of Ophthalmology, May 2007. Web. 26 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ "The Founder of VRMNY, Dr. Yanuzzi Has Made Numerous Innovative." Vitreous Retina Macula Consultants of New York. VRMNY, n.d. Web. 29 Nov. 2016.

- ↑ Dompieri RC, Manzano RPA, Frazão MAM, Kurimori HY, Chao JCT, Lui ACF.Unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy secondary to yellow fever disease: a case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019 May 9;15:100464.

- ↑ Jorge LF, Queiroz RP, Gasparin F, Vasconcelos-Santos DV. Presumed Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy following H1N1 Vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020 Mar 11:1-3. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1734213. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32160085.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Freund KB, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, Spaide RF, Milewski SA, Guyer DR. The Expanding Clinical Spectrum of Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(5):555-559.doi:10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130547007

- ↑ Anjou M, Fajnkuchen F, Nabholz N, Nghiem-Buffet S, Mrejen S, Giocanti-Aurégan A. Multimodal Imaging of Unilateral Acute Maculopathy Associated with Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease: A Case Series. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2022 Aug 16;13(2):617-625.

- ↑ Bleicher ID, Brill D, Wu F, Sobrin L, Patel N. Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022 Sep 2:1-4.

- ↑ Hasegawa T, Sannomiya Y, Toyoda M, Maruko I, Iida T. Acute idiopathic maculopathy after COVID-19 vaccination. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2022 Jun;26:101479.

- ↑ Venkatesh R, Reddy NG, Mishra P, Gupta A, Mahendradas P, Yadav NK. Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy following Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus (SARS-CoV-2) Infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023 Feb;31(2):445-448.

- ↑ Nicolo M, Rosa R, Musetti D, Musolino M, Traverso C. Early Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings in Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016; 47: 180-182. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160126-13

- ↑ Nicolo M, Rosa R, Musetti D, Musolino M, Traverso C. Early Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings in Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016; 47: 180-182. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160126-13

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Nicolo M, Rosa R, Musetti D, Musolino M, Traverso C. Early Swept-Source Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings in Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016; 47: 180-182. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20160126-13

- ↑ Aggio FB, Farah ME, Meirelles RL, Souza EC. STRATUSOCT and multifocal ERG in unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:510–516. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-1172-3

- ↑ Pajtler Rosar A, Bochicchio S, Giani A, Bottoni F, Staurenghi G. ACUTE IDIOPATHIC MACULOPATHY COMPLICATED BY CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION: NEW INSIGHTS INTO MULTIMODAL RETINAL IMAGING. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021 Sep 1;15(5):593-597.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Gupta, A., S. Rogers, and B. N. Matthews. "Unilateral Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy." British Journal of Ophthalmology 93.8 (2009): 1073-074. Web.