Achromatopsia

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Achromatopsia is recognized by the codes per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature.

Disease

Achromatopsia is a rare, bilateral inherited retinal degeneration affecting all three types of cone photoreceptor cells that results in the absecnce of color discrimination. The disease can be complete with total lack of cone function, also known as rod monochromatism, or blue-cone (S cone) monochromatism. Retinal achromatopsia is distinct from cerebral achromatopsia, the latter of which consists of poor color discrimination due to cerebral pathology. Achromatopsia is also distinguished from more common forms of color blindness by the fact that all three types of cones are defective.

Epidemiology

Achromatopsia is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 30,000 individuals worldwide.[1]

The island of Pingelap in the country of Micronesia has a uniquely high achromatopsia prevalence, an observation popularized by the late author Oliver Sacks’ book ‘The Island of the Colorblind.’ After a typhoon in the late 1700s that dramatically reduced the population, the prevalence of achromatopsia rose to almost 10% due to a founder effect and high homozygosity of a mutation in CNGA3.[2]

CNGB3 is the more common achromatopsia gene implicated in Europe and the USA while CNGA3 is the more common gene affected in the Middle East and China.[2][3][4]

Pathophysiology

Rod monochromatism is an autosomal recessive disease affecting all three types of retinal cones. The most common mutations affect genes that code for or regulate cone cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) cation channel subunits, including CNGB3 in 50% of cases and CNGA3 in 25% of cases.[5][6] To date, nearly 100 mutations in CNGA3 and CNGB3 have been linked to achromatopsia in humans. [7] The CNG channels are located on photoreceptor outer segment cell membranes and are involved in signal transduction. These mutations result in a significant decline in cone function. Other implicated genes accounting for a smaller fraction of achromatopsia cases include GNAT2, PDE6C, PDE6H and ATF6.[8][9][10]

Blue cone (S-cone) monochromatism is usually X-linked and it is important to have a family history. In this disease the function of the rods and S cones is normal, but L- and M- cone function is absent.

History

Patients typically present at a young age with hemeralopia, glare, decreased visual acuity, absent or diminished color vision and pendular nystagmus. Nystagmus often develops within the first several weeks of life and is commonly the first symptom noted by parents or pediatricians. Patients with achromatopsia also have a high rate of hyperopia requiring spectacle correction.

There are no systemic abnormalities associated with achromatopsia and patients can expect a normal life expectancy.

Physical Examination

Visual acuity ranges from 20/200 or worse in complete achromatopsia to 20/80 in incomplete achromatopsia. Patients with blue-cone monochromatism may have visual acuity of approximately 20/80, typically better than those with rod monochromatism. Color vision testing is severely or completely diminished and pupillary exam in children can demonstrate a paradoxical pupil, where the pupil initially constricts on dimming of light.[11] Fundus exam can appear normal early in the disease course. Later on, patients may develop retinal pigment epithelial mottling and atrophy. [12]

Diagnostic procedures

Electroretinography (ERG) is the gold standard for the diagnosis of achromatopsia. Cone function is severely or completely diminished while rod function is normal. Additionally, individuals with blue-cone monochromatism have preserved S-cone ERG responses.

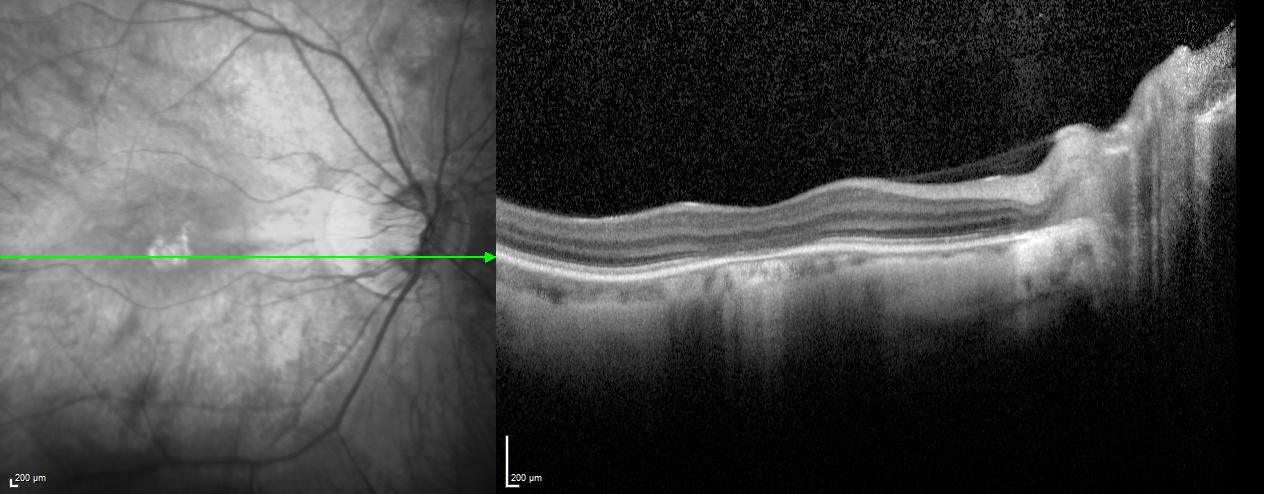

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can provide diagnostic assistance as well as insight into the structure of dysfunctional cone cells. A hyporeflective “optical gap” can be found at the fovea that corresponds to foveal loss of photoreceptor outer segments. This finding is not specific to achromatopsia and can be seen in other retinal degenerations such as Stargardt’s disease, occult macular dystrophy and cone dystrophies.[13] Eventually the hyporeflective area involutes as seen in Figure 1. The disease has been described to go through sequential stages that can be followed on OCT (Table 1).[14] However, a functional decline association with this proposed sequence has not been found.[15][16] The cones may be nonfunctional at birth but still physically present - degradation over time may result in these structural changes without a corresponding change in function. The OCT stages may also not be sequential for all patients and could represent the end-stages of different degrees of cone dysfunction.

Table 1. OCT stages of Achromatopsia

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Intact outer retina |

| 2 | Ellipsoid zone disruption |

| 3 | Optically empty space |

| 4 | Optically empty space with partial retinal pigment epithelium disruption |

| 5 | Outer nuclear layer loss and/or complete retinal pigment epithelial disruption |

Patients often have some degree of foveal hypoplasia. On ERG, cone function is completely or almost completely extinguished with a normal or mostly normal rod function.

Management

Currently there is no approved treatment for achromatopsia. Children should be monitored for associated high hyperopia that can be corrected with spectacles or contacts; however, a wide range of refractive errors have been reported, with myopia occurring in some patients.[17] Any underlying amblyopia can be managed with occlusion or atropine therapy. Clinical research trials, low vision and genetic counseling should be considered for patients and their families.

Genetic testing can help confirm the diagnosis and provide parents with information regarding the risk to other children. A molecular diagnosis is also typically required for consideration of ongoing clinical research trials.

Research

Several phase I/II clinical trails assessing the effectiveness of gene therapy for achromatopsia are currently ongoing. A list can be found through clinicaltrials.gov: Achromatopsia trials.

Gene therapy is emerging as a promising therapeutic tool across medicine and particularly in the field of inherited retinal diseases. Achromatopsia may be a particularly suitable condition for gene therapy as the structural loss of dysfunctional cone photoreceptors occurs relatively late in the disease course. Cone photoreceptors are therefore available for transduction over a longer time period, in contrast to other inherited retinal dystrophies with earlier outer retinal degeneration. A series of 9 patients, published in April of 2020, was found to have promising results following subretinal adenoviral gene therapy targeting CNGA3, with cone photoreceptor activation and improved vision in some adult patients.[18] Some remaining challenges for gene therapy include genetic heterogeneity, surgical challenges in young eyes, development of amblyopia prior to treatment, and need for long-term efficacy.

For patients with the ATF6 mutation, a small trial at Columbia will be investigating gylcerol phenylbutyrate (PBA).

Low vision

Referral to a low vision specialist can be considered, where tinted glasses or contacts can help with debilitating hemeralopia and individualized training can help patients function with low vision.[19][20] Glasses that are reported to help with color discrimination are currently under investigation, but primarily in red-green color deficiencies.[21] Electronic devices that aid with color discrimination are also being investigated. The use of filters of light to reduce photophobia is also being tested and may involve reducing the stimulation of photoreceptors.

Genetic counseling

The disease is autosomal recessive and referral to a genetic counselor should be considered for patients and family members.

Prognosis

Patients typically maintain the vision that develops during childhood. Although symptomatically patients often remain stable, several studies have suggested that age-related development of foveal structural changes may indicate a slowly progressive degeneration and loss of cone photoreceptor cells in affected patients.[15] [22][23] [24]A longitudinal study of 17 patients in Italy found a slow deterioration of the macular structure in the years following diagnosis.[25] A recent study of 53 patients in the Middle East suggested no deterioration of visual acuity with age. In fact, slight improvement over time was seen. The authors note that this improvement may reflect increased maturation of attention or general cognitive abilities of younger study participants as they aged. As such, the “improvement” in vision observed may not necessarily reflect a significant improvement but rather the absence of significant deterioration.[4] Further research is warranted.

[SC1]Citation: Add reference of new study of achromatopisa in Middle East: Eshel YM, Abaev O, Yahalom C. Achromatopsia: Long term visual performance and clinical characteristics. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2023;0(0)

References

- ↑ Aboshiha J, Dubis AM, Carroll J, Hardcastle AJ, Michaelides M. The cone dysfunction syndromes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(1):115-121.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Sheffield VC. The vision of typhoon lengkieki. Nat Med. 2000 Jul;6(7):746-7.

- ↑ Mayer AK, Van Cauwenbergh C, Rother C, Baumann B, Reuter P, De Baere E, et al. CNGB3 mutation spectrum including copy number variations in 552 achromatopsia patients. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(11):1579–1591.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Eshel YM, Abaev O, Yahalom C. Achromatopsia: Long term visual performance and clinical characteristics. European Journal of Ophthalmology. 2023;0(0). doi: 10.1177/11206721231212768

- ↑ Kohl S, Varsanyi B, Antunes GA, Baumann B, Hoyng CB, Jägle H, et al. CNGB3 mutations account for 50% of all cases with autosomal recessive achromatopsia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005 Mar;13(3):302-8.

- ↑ Kohl S, Marx T, Giddings I, Jägle H, Jacobson SG, Apfelstedt-Sylla E, et al. Total colourblindness is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the alpha-subunit of the cone photoreceptor cGMP-gated cation channel. Nat Genet. 1998 Jul;19(3):257-9.

- ↑ Michalakis S, Gerhardt M, Rudolph G, Priglinger S, Priglinger C. Achromatopsia: Genetics and Gene Therapy. Mol Diagn Ther. 2022 Jan;26(1):51-59.

- ↑ Felden J, Baumann B, Ali M, et al. Mutation spectrum and clinical investigation of achromatopsia patients with mutations in the GNAT2 gene. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(8):1145-1155. doi:10.1002/humu.23768

- ↑ Weisschuh N, Stingl K, Audo I, et al. Mutations in the gene PDE6C encoding the catalytic subunit of the cone photoreceptor phosphodiesterase in patients with achromatopsia. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(10):1366-1371. doi:10.1002/humu.23606

- ↑ Ritter M, Arno G, Ba-Abbad R, Holder GE, Webster AR. Macular maldevelopment in ATF6-mediated retinal dysfunction. Ophthalmic Genet. 2019;40(6):564-569. doi:10.1080/13816810.2019.1706749

- ↑ Flynn JT, Kazarian E, Barricks M. Paradoxical pupil in congenital achromatopsia. Int Ophthalmol. 1981 Mar;3(2):91-6.

- ↑ Thiadens AA, Somervuo V, van den Born LI, et al. Progressive loss of cones in achromatopsia: an imaging study using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51(11):5952–5957.

- ↑ Oh JK, Ryu J, Lima de Carvalho JR,Jr, Levi SR, Lee W, Tsamis E, et al. Optical Gap Biomarker in Cone-Dominant Retinal Dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020 May 20.

- ↑ Greenberg JP, Sherman J, Zweifel SA, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography staging and autofluorescence imaging in achromatopsia. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(4):437-445. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.7987

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Zobor D, Werner A, Stanzial F, et al. The Clinical Phenotype of CNGA3-Related Achromatopsia: Pretreatment Characterization in Preparation of a Gene Replacement Therapy Trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(2):821-832. doi:10.1167/iovs.16-20427

- ↑ Aboshiha J, Dubis AM, Cowing J, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of retinal structure and function in achromatopsia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(9):5733-5743. Published 2014 Aug 7. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-14937

- ↑ Brunetti-Pierri R, Karali M, Melillo P, Di Iorio V, De Benedictis A, Iaccarino G, Testa F, Banfi S, Simonelli F. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of Achromatopsia Patients: A Longitudinal Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 7;22(4):1681

- ↑ Fischer MD, Michalakis S, Wilhelm B, Zobor D, Muehlfriedel R, Kohl S, et al. Safety and Vision Outcomes of Subretinal Gene Therapy Targeting Cone Photoreceptors in Achromatopsia: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020 Apr 30;138(6):1-9.

- ↑ “Use of modified X-Chrom for relief of light dazzlement and color blindness of a rod monochromat.” JAOA 1979;50(7)

- ↑ Schornack MM, Brown WL, Siemsen DW. The use of tinted contact lenses in the management of achromatopsia. Optometry. 2007;78(1):17-22. doi:10.1016/j.optm.2006.07.012

- ↑ Gómez-Robledo L, Valero EM, Huertas R, Martínez-Domingo MA, Hernández-Andrés J. Do EnChroma glasses improve color vision for colorblind subjects?. Opt Express. 2018;26(22):28693-28703. doi:10.1364/OE.26.028693

- ↑ Sundaram V, Wilde C, Aboshiha J, et al. Retinal structure and function in achromatopsia: implications for gene therapy. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:234–245.

- ↑ Thiadens AAHJ, Somervuo V, van den Born LI, et al. Progressive loss of cones inachromatopsia: an imaging study using spectral-domain optical coherence tomog-raphy.Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5952–5957.

- ↑ Andersen MKG, Bertelsen M, Grønskov K, Kohl S, Kessel L. Genetic and Clinical Characterization of Danish Achromatopsia Patients. Genes (Basel). 2023 Mar 10;14(3):690. doi: 10.3390/genes14030690.

- ↑ Brunetti-Pierri R, Karali M, Melillo P, Di Iorio V, De Benedictis A, Iaccarino G, Testa F, Banfi S, Simonelli F. Clinical and Molecular Characterization of Achromatopsia Patients: A Longitudinal Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 7;22(4):1681.