Subperiosteal Hematoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Orbital subperiosteal hematoma, commonly called orbital subperiosteal hemorrhage, is a rare condition defined by a collection of blood within the potential space between the periosteum and the bones of the orbit. Rapid expansion of an orbital subperiosteal hematoma has the potential to compress the optic nerve and cause permanent ocular deficits.[1] Prompt diagnosis and appropriate initiation of treatment can prevent these potentially serious consequences.

Epidemiology

Orbital subperiosteal hematomas are rare with fewer than 20 cases reported in the literature.[2] However, true incidence and prevalence are unknown at this time, as cross-sectional studies have not been undertaken.

Etiology

Orbital subperiosteal hematomas (OSH) occur most commonly due to facial trauma and less commonly secondary to nontraumatic causes. Traumatic causes are frequently associated with a fracture of the involved orbital bone and direct or shearing forces that lead to bleeding and development of an orbital subperiosteal hematoma. Though rare, many case reports have been published on non-traumatic causes of orbital subperiosteal hematomas.[3][4] There have been reports citing orbital inflammation, vascular and metabolic disorders, systemic diseases affecting platelet levels and idiopathic cases of non-traumatic orbital subperiosteal hematomas. Causes of increased venous congestion include emesis[5], weight-lifting, Valsalva maneuver such as during child birth, and scuba diving. Systemic associations such as sickle cell disease,[6] lung cancer,[7] chronic myelogenous leukemia,[8] disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and coagulopathy secondary to liver disease have also been reported. Additionally, patients with sinusitis[9][10][11] have been reported to develop a non-traumatic orbital subperiosteal hematoma.

Risk Factors

The most common risk factor for the occurrence of an orbital subperiosteal hematoma is a recent trauma. For a non-traumatic orbital subperiosteal hematoma, risk factors include an increase in central venous congestion and a bleeding diathesis. Traumatic OSH, unsurprisingly, has been reported to occur more commonly in young males.[12] Non-traumatic OSH is more commonly seen in females.

Anatomy

The periosteum of the orbit is referred to as the periorbita. It is unique in that it is not tightly affixed to the underlying bone except in specific areas, such as the optic canal, orbital fissures, orbital margins, and at foramina for neurovascular elements crossing the periorbita. As part of normal aging, the periosteum gradually becomes tightly affixed to the underlying orbital bone through the process of calcification. The diploic veins that traverse the potential space between periosteum and orbital bone are susceptible to rupture. Once calcification is complete, the periosteum is more tightly adhered to the bone, offering a measure of resistance to the flow of low-pressure venous blood into this potential space.

Pathophysiology

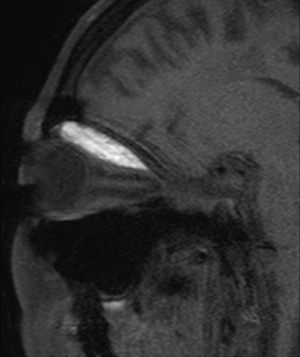

Orbital subperiosteal hemorrhage is caused by rupture of diploic veins between the periosteum (periorbita) and the bony orbit. Rupture causes a local hemorrhage with subsequent hematoma formation between the periorbita and bone. The space-occupying blood increases pressure, causing the periorbita to peel away from the bone. If the periorbita remains intact blood will not enter the orbit and imaging will reveal a bilenticular shape to the hematoma. An untreated orbital subperiosteal hematoma may enlarge over time or spontaneously resolve. A 2013 case series[13] found that 9 of 11 patients with CT-confirmed orbital subperiosteal hematomas displayed a superior orientation within the orbit.

Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of OSH rests on the combination of physical exam findings and confirmatory imaging. The most common location is a superior and medial orientation of the hematoma involving the orbital plane of the frontal bone. [5][9] Non-contrast CT is the imaging modality of choice due to its capacity to highlight blood between the periosteum and bony orbit. CT imaging has the advantage of distinguishing acute from subacute or hyperacute states on the basis of signal intensity.[14] MRI is inferior due to difficulty in distinguishing boney structures but this modality can highlight such hematomas as hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging. CT and MRI are superior to ultrasound imaging, and orbital plain films have no role in diagnosis. In idiopathic cases of non-traumatic OSH, a pathologic assessment of the evacuated fluid can determine whether the hematoma is of hematologic or neoplastic origin.

History and Physical

It is important to gather a complete history and full ophthalmologic exam on any patient suspected of having an OSH. A history of facial trauma or barotrauma is frequently revealed. When recent trauma has not occurred, a history of valsalva maneuver, bleeding diathesis, anticoagulation therapy, acute sinusitus, and other systemic diseases should be pursued. Testing of extraocular motility and Hertel exophthalmometry commonly reveals gaze restriction and proptosis. Careful pupillary assessment for evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect is of utmost importance to rule out optic nerve compression. Similarly, color vision testing is quite useful. Globe dystopia may occur with a sufficiently large hematoma. Intraocular pressure is commonly elevated and should be compared to the contralateral eye.

Signs

Signs may include proptosis, extraocular motility restriction, decreased visual acuity, increased intraocular pressure, a relative afferent pupillary defect, eyelid edema and ecchymosis, and resistance to retropulsion.[15][16] Deficits are typically unilateral, but there are case reports of bilateral OSH due to attempted suicide, sustained headlock, and following mitral valve repair.[17][18][19][20]

Symptoms

Symptoms include pain, diplopia, decreased visual acuity and subjective color desaturation.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis varies, depending on the clinical presentation but may include acute orbital hemorrhage, subperiosteal abscess, mucocele, and eosinophilic granuloma. OSH may evolve into a hematic cyst if allowed to remain untreated for a sufficiently long period of time.

Management

Treatment depends on the clinical findings of OSH, specifically whether there is evidence of optic nerve compression. Possible treatments include observation, fine-needle aspiration, corticosteroids, anterior orbitotomy, and/or endoscopic drainage. Prompt intervention is warranted if a relative afferent pupillary defect is present. Surgery[13] to decompress an OSH may be the treatment of choice if a compressive optic neuropathy component is present or in non-traumatic cases, if suspicion of tumor is high. Drain placement may prevent recurrence of the hematoma. Authors have also described using FNA for acute resolution of OSH in which neurological signs indicated urgent intervention.[21] Corticosteroids for associated edema has achieved resolution when a non-invasive, conservative approach was deemed appropriate.[16] Similarly, one case of migraine with emesis-induced OSH demonstrated rapid resolution under close observation without recurrence of OSH after subsequent emesis.[5]

References

- ↑ Kataria R, Kumar V, Mehta V. Traumatic bilateral orbital subperiosteal hematoma with vision loss. Neurology India. 2010; 58(3):495-497.

- ↑ Li W, Kinde B, Clauss KD, Tse BC. Spontaneous Subperiosteal Orbital Hematoma Associated With Cocaine-Induced Midline Destructive Lesion. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 Jul-Aug 01;39(4):e123-e126. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002382. Epub 2023 Mar 27. PMID: 36972112.

- ↑ McNab AA. Non-traumatic orbital hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol 2014;59:166–184.

- ↑ Saeed HN1, Presta MV, Yoo D. Subperiosteal haematoma after general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2014 Apr;112(4):772-3

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Reid J, Rajak S, Good C, Brittain G. Emesis-induced sub-periosteal haematoma: a case report. Orbit. 2014:33(3):226-228.

- ↑ Ozkavucku E, Fitoz S, Yagmurlu B, Ciftci E, Erden I, Ertem M. Orbital wall infarction mimicking periorbital cellulitis in a patient with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2007; 37:388-390.

- ↑ Capua J, Stiner E, Li T. Spontaneous subperiosteal orbital hematoma as initial presentation of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma to the skull: case report. Orbit. 2014;33(2):152-155.

- ↑ Yoon M, McCulley T. Non-traumatic subperiosteal hematoma as a presenting sign of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Ophthalmic Plastics & Reconstructive Surgery. 2012; 28(4):e79-e80.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Nomura K, Honkura Y, Ozawa D, Okumara Y, Hidaka H, Ogawa T, Yamauchi D, Watanabe K, Katori Y. Endoscopic drainage of orbital subperiosteal hematoma secondary to acute rhinosinusitis in a child. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;233:171-174.

- ↑ Kim J, Lee H, Baek S. Orbital subperiosteal hematoma associated with frontal and ethmoidal sinusitis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar 3;22(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12886-022-02324-y. PMID: 35241018; PMCID: PMC8895574.

- ↑ Wong BM, Leppard JLA. Spontaneous subperiosteal orbital hematoma in a patient with chronic sinusitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Oct;48:279-281. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.05.028. Epub 2021 May 13. PMID: 34022635.

- ↑ Kim U, Arora V, Shah A, Solanki U. Clinical features and management of posttraumatic subperiosteal hematoma of the orbit. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(1):55-58.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Elia M, Shield D, Kazim M, Shinder R, Yoon M, McCulley T, Shore J, Greene D, Servat J, Levin F. Spontaneous subperiosteal orbital hemorrhage. Orbit. 2013;32(5):333-335.

- ↑ Atalla ML, McNab AA, Sullivan TJ, Sloan B. Nontraumatic subperiosteal orbital hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2001; 108:183-189.

- ↑ Amissah-Arthur K, Groppe M, Scotcher S. Orbital subperiosteal hematoma after thrombolysis and anticoagulation for acute myocardial infarction. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2009;29(3): 250-251.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Crawford C, Mazzoli R. Subperiosteal hematoma in multiple settings. Digital Journal of Ophthalmology. 2013. www.djo.harvard.edu. Accessed 8/9/2015.

- ↑ Sakurai K, Morita S, Otsuka H, Sugita M, Taira T, Nakagawa Y, Inokuchi S. Non-traumatic bilateral orbital subperiosteal hematoma in a person who attempted suicide by hanging. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39(3):103-105.

- ↑ Belloni E, Pauroso S, Scagnelli P. Bilateral Orbital Subperiosteal Hematoma in Attempted Suicide by Hanging. Neurol India. 2022 Sep-Oct;70(5):2306-2307. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.359220. PMID: 36352690.

- ↑ Crawford S, Patel M. Bilateral supraorbital masses after prolonged headlock injury: an unusual manifestation of orbital subperiosteal hematomas. Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 184:S2-S3.

- ↑ Mangla D, Carruth BP, Britton LW, Wladis EJ. Nontraumatic subperiosteal bilateral orbital hemorrhages after mitral valve repair. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Jan-Feb;30(1):e1-2.

- ↑ Chelnis J, Pihlblad M, Jung H, Schaefer D. Office-based needle aspiration of idiopathic acute subperiosteal hematoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013; 48(5):e133-e134.