Siegrist Streaks and Elschnig Spots

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Siegrist streaks are manifestations of hypertensive choroidopathy, which are associated with malignant hypertension, defined as blood pressure of 180/120 mmHg in association with end-organ damage. [1] They are named after the Swiss ophthalmologist August Siegrist, who initially documented these in 1899[2] after noticing a pattern of retinal lesions in two patients, one with giant cell arteritis and another with malignant hypertension. These lesions are commonly associated with giant cell arteritis and other inflammatory vascular etiologies.[3] On histological exam, Siegrist streaks tend to appear as sclerosed choroidal vessels with overlying necrosis of the choriocapillaris, which leads to secondary retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) atrophy.[4] The streaks can also develop reactive RPE hyperplasia and hypertrophy along the margins even 2-3 weeks after the initial onset of the choroidal ischemia.[5]

Discovered in the 1900s in Prague, the Elschnig spots are named after Austrian Ophthalmologist Anton Elschnig. Elschnig spots are small isolated circular areas with central RPE clump,[6] and surrounding areas of depigmentation. They occur secondary to infarctions or fibrinoid necrosis of the choriocapillaris that cause changes in the overlying RPE.[7] The spots can occur in isolation, unlike Siegrist streaks, which occur along the course of sclerosed choroidal vessels.

Risk factors/Pathophysiology

The primary etiologies of Siegrist streaks are usually malignant hypertension and giant cell arteritis (GCA), with causation more commonly linked to severe systemic arterial hypertension.[7][8][9] Diseases associated with malignant hypertension may also cause Siegrist streaks, including documented cases of preeclampsia/HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) syndrome, adrenal carcinomas, as well as more rare illnesses such as Takayasu arteritis.[10][11][12][13]

The retina receives dual blood supply from the branches of the ophthalmic artery, with the inner retina being supplied from the central retinal artery and the outer choroid and retina being supplied by the long and short posterior ciliary arteries.[14] The posterior ciliary artery also serves as the main arterial blood supply of the choroid. The choroidal bed also differs from the retinal vascular bed in that the former lacks an autoregulatory mechanism for blood flow and has no blood-ocular barrier; this serves in contrast to the retinal vasculature, which has a blood-retinal barrier and autoregulation of the blood supply. Because of these factors, the choroid and retinal vascular beds have differing reactions to elevated blood pressure and ischemia.[7]

The pathophysiology of Siegrist streaks and Elschnig spots are similar. The choroid is the layer between the RPE and sclera, and it receives blood flow from the short and long posterior ciliary arteries. Accelerated hypertension and/or ophthalmic ciliary artery occlusion (from GCA or other vasculitides) can lead to choroidal ischemia and, thus, hypertensive choroidopathy.[15] Siegrist streak pathophysiology stems from an initial acute marked elevation in systemic blood pressure, causing acute multifocal areas of fibrin platelet occlusion and necrosis of the choriocapillaris. This leads to corresponding RPE necrosis of the area and then sclerosis of the same choriocapillaris in a patchy distribution. Eventually, the sclerotic choroidal vessels undergo hyperpigmentation, leading to the appearance of Siegrist streaks. Elschnig spots stem from similar pathophysiology but are secondary to the focal destruction of the choriocapillaris due to nonperfusion after an acute insult, ischemia, or necrosis. In summary, choroidal infarcts manifest at Elschnig spots and fibrinoid necrosis of tissue overlying a sclerosed choroidal vessel.

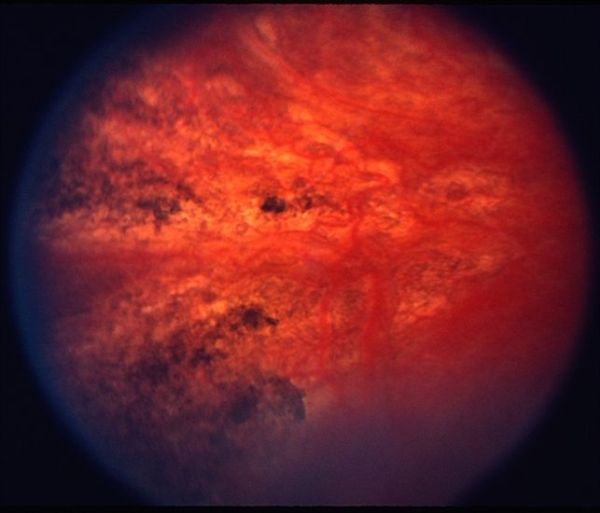

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of Siegrist Streaks and Elschnig Spots

Diagnosis

Exam Findings

Physical examination of the patient should focus on vital sign acquisition in addition to a complete cardiovascular, pulmonary, neurological, and dilated fundus exam. Patients should be asked for a detailed history and checked for symptoms of hypertension such as headaches, eye pain, reduced visual acuity, chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, and palpitations. An inquiry should also include any history of complications from hypertension, including but not limited to a history of coronary or vascular disease, history of stroke or TIA (transient ischemic attack), or history of heart failure, though patients may present as asymptomatic given compensatory baroreceptor adjustments.[16]

Clinical presentation may include blurred vision for a period of months, specifically in a known hypertensive patient, and this may coincide with a history of vasculitis, leading to sudden vision loss in one or both eyes.[3][17] On dilated fundus exam, Siegrist streaks appear as linear configurations of hyperpigmentation that develop over choroidal arteries. Elschnig spots appear as yellow demarcated lesions, primarily in the temporal perimacular region.[15] These are the non-perfused areas of the choriocapillaris and are pale or gray-yellow in color with well-defined margins.[18] Acute Elschnig spots may be associated with subretinal fluid pockets. Once scarred, there may be central pigment seen within the atrophic region.

Other potential common lab findings: see GCA findings.

Common causes of malignant hypertension must be ruled out. These include

- Essential hypertension

- Secondary hypertension- Pregnancy-induced hypertension, renal diseases, endocrine disorders including pheochromocytoma, coarctation of the aorta, and hypertension caused by toxicity of drugs.

Investigations

Diagnostic testing for Siegrist streaks may show linear granular or mottled autofluorescence when in the active stage of hypertensive choroidopathy. Later in the disease progression, hypo-autofluorescence may be seen, indicating RPE atrophy has occurred. On Humphrey Visual Field testing, a noticeable visual field defect can be found corresponding to the area of necrosis.[19] On the OCT-A exam, multiple flow voids may be noted corresponding to the areas of choriocapillaris nonperfusion.[20]

Elschnig spots on indocyanine green and fluorescein angiography may demonstrate leakage in the early stages with patchy or delayed choroidal filling. Fluorescein angiography may show focal areas of hyperfluorescence consistent with window defects. When healed, Elschnig spots do not demonstrate fluorescein leakage, but there may be transmission defects or blocking that appear in the hyperpigmented area with surrounding hyperfluorescence.[21] There may also be other findings seen typically with hypertensive retinopathy. On autofluorescence, hypo-autofluorescence may be seen in the areas of Elschnig spots.[15] OCT may show areas of subretinal fluid over acute Elschnig spots.

Differential diagnosis

Severe choroidal ischemia or posterior choroidal arterial occlusion can manifest as white areas in a triangular region, the so-called Amalric sign.[22] Such areas may be noted in various disorders, including ophthalmic arterial occlusion,[23] polyarteritis nodosa associated vasculitis, [24] and cocaine toxicity.[25] Areas of choroidal infarct may be noted in multiple disorders, including diseases associated with thrombosis, vascular occlusion, or vasculitis.

Management

The management includes the management of hypertension and its cause. With systemic optimization, the acute effects of hypertensive choroidopathy, including subretinal fluid, usually resolve.

See Hypertensive Choroidopathy.

Additional Resources

- Porter D, Vemulakonda GA. Blood Pressure. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/anatomy/blood-pressure-list. Accessed January 06, 2023.

References

- ↑ Naranjo M, Chauhan S, Paul M. Malignant Hypertension. [Updated 2022 Apr 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507701/

- ↑ Siegrist, August. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der arterosklerose der Augengefasse. In: IX Int Cong Ophthalmol. Published online 1899:131-139.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Coupal DJ, Patel AD. Siegrist Streaks in Giant Cell Arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2003;23(4):272-273.

- ↑ Perlman J, Hines E. Systemic diseases with retinal involvement. In: Ophthalmic Pathology: An Atlas and Texbook,. Vol 2. WB Saunders; 1985:1034-1037.

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125(4):509-520. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80192-5

- ↑ Morse P. Elschnig’s spots, and hypertensive choroidopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;(66):844-852.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hayreh SS, Servais GE, Virdi PS. Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. VI. Hypertensive choroidopathy. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(11):1383-1400. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33554-1

- ↑ Duke-Elder S. Diseases of the Uveal Tract. In: System of Ophthalmology. Vol 9. Mosby; 1966:1034-1037.

- ↑ Puri P, Watson AP. Siegrist’s streaks: A rare manifestation of hypertensive choroidopathy. Eye. 2001;15(2):233-234. doi:10.1038/eye.2001.70

- ↑ Rohart C, Abad S, Badelon I, et al. TAKAYASU DISEASE REVEALED BY BILATERAL LOSS OF VISION. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2009;3(2):174-176. doi:10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181607a26

- ↑ Rahhal-Ortuño M, Fernández-Santodomingo AS, Barreiro-González A, Díaz-Llopis M. Hypertensive choroidopathy and adrenal carcinoma: A new association. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol Engl Ed. 2019;94(1):37-40. doi:10.1016/j.oftale.2018.09.007

- ↑ Interlandi E, Pellegrini F, Silvestrin C, Pece A, Pavesio C. Hellp syndrome-related hypertensive chorioretinopathy: A multimodal imaging and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) study. Eur J Ophthalmol. Published online October 12, 2021:11206721211051238. doi:10.1177/11206721211051238

- ↑ Bourke K, Patel MR, Prisant LM, Marcus DM. Hypertensive Choroidopathy. J Clin Hypertens. 2004;6(8):471-472. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.3749.x

- ↑ Fraser-Bell S, Symes R, Vaze A. Hypertensive eye disease: a review. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2017;45(1):45-53. doi:10.1111/ceo.12905

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bourke K, Patel MR, Prisant LM, Marcus DM. Hypertensive Choroidopathy. J Clin Hypertens. 2004;6(8):471-472. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.3749.x

- ↑ Katakam R, Brukamp K, Townsend RR. What is the proper workup of a patient with hypertension? Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(9):663-672. doi:10.3949/ccjm.75.9.663

- ↑ Patel A, Panchal B, Pathengay A. Role of autofluorescence in Siegrist streaks. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;1(1):133-134.

- ↑ Wilkinson CP, Hinton D, Sadda S, Wiedemann P. Ryan’s Retina. 6th Edition. Elsevier; 2017.

- ↑ Hypertensive Choroidopathy: a Teaching Case Report. :8.

- ↑ Interlandi E, Pellegrini F, Silvestrin C, Pece A, Pavesio C. Hellp syndrome-related hypertensive chorioretinopathy: A multimodal imaging and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) study. Eur J Ophthalmol. Published online October 12, 2021:11206721211051238. doi:10.1177/11206721211051238

- ↑ Ugarte M, Horgan S, Rassam S, Leong T, Kon CH. Hypertensive choroidopathy: recognizing clinically significant end-organ damage. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 2008;86(2):227-228. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01030.x

- ↑ Amalric P. Acute choroidal ischemia. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K (1962). 1971;91:305-322.

- ↑ Hande P, Sinha B, Nayak S, Srinivasan S, Shetty J. Amalric sign: An augur of ophthalmic artery occlusion. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(10):1033-1035. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_42_17

- ↑ Hsu CT, Kerrison JB, Miller NR, Goldberg MF. Choroidal infarction, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and central retinal artery occlusion from polyarteritis nodosa. Retina. 2001;21(4):348-351. doi:10.1097/00006982-200108000-00009

- ↑ Reddy S, Goldman DR, Hubschman JP, Kaines A, Sarraf D. Cocaine and choroidal infarction, revisiting the triangular sign of Amalric. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2011;5(1):91-93. doi:10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181e2506f