Melanoma Associated Retinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR) is a paraneoplastic syndrome that primarily affects individuals with metastatic cutaneous or uveal melanoma. MAR is driven by an autoimmune response where antiretinal antibodies attack retinal antigens, resulting in progressive, painless visual decline. Common symptoms include photopsia, night blindness, and visual field loss[1][2]. Evaluation with electroretinography (ERG) can identify characteristic changes from abnormalities in bipolar cell function.

Disease Entity

Disease

MAR is a paraneoplastic syndrome that typically presents after the diagnosis of melanoma. This condition primarily affects individuals with metastatic cutaneous or uveal melanoma and manifests as progressive, bilateral, and painless visual deterioration[1][2]. The visual symptoms generally include a sudden onset of shimmering, flickering photopsias, night blindness, and progressive vision loss over several months, with characteristic peripheral visual field depression or mid-peripheral visual field loss[3].

Etiology

MAR arises due to an autoimmune response where the immune system aberrantly creates autoantibodies against retinal antigens, leading to retinal degeneration [1][2]. These antibodies are primarily reactive against retinal bipolar cells, although reactivity against other retinal cell populations has been implicated[2].

Risk Factors

The primary risk factor for MAR is the presence of metastatic melanoma, particularly cutaneous or uveal melanoma[1][2]. It is more commonly observed in men than in women[2]. The development of MAR is also associated with alterations in the immunological environment by melanoma, which may predispose the retina to autoimmune reactions.

General Pathology

Pathologically, MAR involves the degeneration of retinal structures due to the autoimmune reaction triggered by antiretinal antibodies. Fundus examination may show a range from normal appearance to signs of optic nerve pallor, vessel attenuation, RPE changes, and vitreous cell presence[1][2]. These findings indicate an ongoing inflammatory and degenerative process in the retina.

Pathophysiology

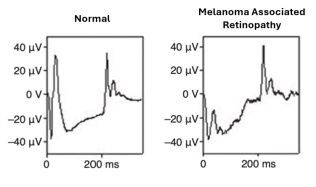

The pathophysiology of MAR is centered around the autoimmune response against retinal antigens. Specifically, the antiretinal antibodies in MAR primarily target the bipolar cells[2], which is evident from electroretinography findings showing a marked reduction in the b-wave. This indicates compromised bipolar cell function while the photoreceptor cell function remains relatively normal, leading to an electronegative ERG[4]. This selective involvement contributes to the characteristic visual symptoms associated with MAR.

Primary Prevention

Currently, there is no direct method for the primary prevention of MAR as it is an autoimmune response secondary to the presence of melanoma. The emergence of MAR symptoms could signal a recurrence of melanoma and/or metastasis[5].

Diagnosis

History

In patients suspected of having MAR, the medical history often reveals a previous diagnosis of melanoma[1]. The history might also include recent changes in vision, especially symptoms like photopsias, night blindness, and progressive visual field loss[1][2].

Physical Examination, Signs, and Symptoms

Patients with MAR may or may not be symptomatic. Diagnosis may also be delayed because the presenting symptoms can be mistaken for other conditions such as PVD, acute idiopathic blind-spot enlargement, migraine with visual aura, or functional visual loss[2]. Common symptoms[3] reflect the dysfunction of bipolar cells and photoreceptors:

- Sudden onset of shimmering or flickering lights

- Difficulty seeing in dim lighting or at night

- Progressive deterioration of visual fields

Symptoms usually become bilateral within days to months, but less commonly can remain unilateral[2]. While ophthalmic examination of a patient with MAR is usually unremarkable, the following signs[2] may indicate a degree of retinal atrophy and ongoing inflammatory processes within the eye:

- Optic nerve pallor

- Retinal vessel attenuation

- Retinal pigment epithelium loss

- Granular macular appearance

Clinical Diagnosis

MAR should be suspected in a patient with the characteristic signs and symptoms and a known history of melanoma. The diagnosis is supported by findings from visual field tests and electroretinography. MAR is classically defined as a triad[2] of:

- nyctalopia, positive visual phenomena, and/or visual field defects

- electronegative ERG

- serum autoantibodies that are reactive with retinal bipolar cells

Diagnostic procedures

- Fundus examination may reveal retinal abnormalities or optic nerve changes; however, examination is usually unremarkable[2]. See Physical Examination, Signs, and Symptoms for notable findings.

- Fluorescein angiography may show blockage and hypo-fluorescence[6].

- ERG is essential for assessing the functionality of the retinal cells, specifically showing reductions in the b-wave amplitude[4].

Laboratory test

The presence of serum autoantibodies against retinal bipolar cells by western blotting and immuno-histochemical staining techniques is considered confirmatory for MAR; however, the absence of these autoantibodies does not rule out the diagnosis[2]. While many advancements have been made in identifying serum autoantibodies, it is still a challenge to determine which are benign and which are implicated in the disease[7]. Below are some of the autoantibodies thought to contribute to the paraneoplastic syndrome [1][7][8][9][10][11]:

- TRPM1 (melastatin 1 or MLSN1)

- TRPM3

- Muller cell protein

- Neuronal antigen

- Retinal bipolar cells

- Transducin

- Rhodopsin

- Arrestin

- Carbonic anhydrase II

- Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein

- Bestrophin

- Alpha-enolase

- Myelin basic protein

- Rod outer segment proteins

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for MAR should consider other causes of visual loss and retinopathies, such as:

- Cancer-associated retinopathy is most associated with small-cell lung carcinoma but may be due to other causes. ERG findings can be used to differentiate between the two as CAR commonly presents with reductions in both the a-wave and b-wave amplitudes.

- Inherited retinal dystrophies such as retinitis pigmentosa and congenital stationary night blindness

- Infectious retinitis especially in immunocompromised patients.

- Non-paraneoplastic autoimmune retinopathy (npAIR) should be considered when no malignancy is detected as it can present with similar symptoms and ERG findings.

- Autoimmune-related retinopathy and optic neuropathy (ARRON) should also be considered when no malignancy is detected. ERG may be variable, but disc pallor may be noted on fundus examination as the distinguishing factor[1].

- Paraneoplastic optic neuropathy (PON) is a disease entity that is also linked to cancer, but findings of visual symptoms are often present before a diagnosis of cancer is made. ERG findings are typically normal, but because of involvement with the optic nerve, atrophy and disc pallor can be noted on examination.

- Toxic retinopathy

Management

General treatment

The treatment of melanoma-associated retinopathy is challenging and primarily focuses on the dual methods of cytoreduction and immunotherapy[2].

Medical therapy

Radiation and chemotherapy are first-line therapies in treating melanoma. In MAR, it has been shown that treating the primary cancer (melanoma) may improve therapeutic outcomes when combined with the below treatment agents:

- Corticosteroids: Oral, sub-tenon, or intravenous corticosteroids may help reduce inflammation and autoimmune activity, but they have not been proven to be effective in MAR[12]. In a case series[1], oral prednisolone provided questionable reduction in visual symptoms in 1 patient whereas visual symptoms continued to progress in the remaining 6 patients.

- Immunosuppressive agents: Medications like azathioprine and cyclosporine can be used to modulate the immune system's activity against retinal cells. These medications may help reduce the damage to the retinal bipolar cells due to the autoantibodies involved in the condition. They have been used sparsely in treatment but when used, have shown improvement in visual fields as well as electroretinography in combination with other treatments[1].

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg): IVIg can help modulate immune responses and is used in various autoimmune disorders. It has been shown to reduce visual symptoms in a case report by improving the visual fields[13], but it is speculated that it could increase cancer mortality due to the possibility of protective antibodies against melanoma being compromised by treatment[1]. Nevertheless, IVIg may be a promising treatment option as many patients have responded positively to the therapy[12].

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Medications such as ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab have been investigated as therapeutic options for MAR. In a systematic review, it was shown that in 37.5% of patients, antitumor efficacy was a complete response, in 50% of patients a partial response, and in one case the disease was stable[14].

- Plasmapheresis: Aimed at removing antibodies from the blood, plasmapheresis has shown to be beneficial in only a few cases. The success of this method has limited evidence[12].

- Gabapentin can be used to manage photopsia symptoms[1].

- Triple therapy: Rituximab, IVIg, and intravitreal corticosteroids concurrently have been shown to revert to baseline visual acuity and electroretinography in one case report[15].

Medical follow up

Regular follow-up is essential to monitor the progression of retinal changes and the response to treatment. Follow-up appointments should involve:

- Comprehensive eye examinations

- Reassessment of visual fields

- Adjustments to therapy based on symptom control and side effects

Surgery

Cytoreductive therapy, either with surgery for metastasectomy, chemotherapy or radiation, should be considered for reducing the tumor burden and hence the production of autoantibodies[2]. Further surgical interventions in MAR are not typically indicated as the primary mode of treatment; however, surgeries may be required to address complications.

Prognosis

On average, individuals with MAR live for approximately 5.9 years after diagnosis, although the range can span from 1 year to decades[16]. The visual outcome largely depends on the extent of retinal damage at the time of diagnosis and the effectiveness of managing the underlying melanoma. Studies on advanced stages of melanoma revealed a correlation between antibodies and a more favorable prognosis, suggesting that autoantibodies might have a protective function in eliminating melanoma cells, diminishing tumor dissemination, and extending survival [2][17]. The emergence of MAR symptoms could signal a recurrence of melanoma and/or metastasis[5].

Additional Resources

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) provides information on rare disorders, including MAR, and supports patients and healthcare professionals with resources and advocacy.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Keltner JL, Thirkill CE, Yip PT. Clinical and Immunologic Characteristics of Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy Syndrome: Eleven New Cases and a Review of 51 Previously Published Cases: J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21(3):173-187. doi:10.1097/00041327-200109000-00004

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 Elsheikh S, Gurney SP, Burdon MA. Melanoma‐associated retinopathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45(2):147-152. doi:10.1111/ced.14095

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Singh AD, Milam AH, Shields CL, Potter PD, Shields JA. Melanoma-associated Retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(3):369-370. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(14)71185-7

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Scholl HPN, Zrenner E. Electrophysiology in the Investigation of Acquired Retinal Disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45(1):29-47. doi:10.1016/S0039-6257(00)00125-9

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Pföhler C, Haus A, Palmowski A, et al. Melanoma-associated retinopathy: high frequency of subclinical findings in patients with melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(1):74-78. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05377.x

- ↑ Zacks DN, Pinnolis MK, Berson EL, Gragoudas ES. Melanoma-associated retinopathy and recurrent exudative retinal detachments in a patient with choroidal melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(4):578-581. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)01086-8

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Grewal DS, Fishman GA, Jampol LM. Autoimmune retinopathy and antiretinal antibodies: a review. Retina. 2014;34(5):827-845. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000119

- ↑ Duvoisin RM, Haley TL, Ren G, Strycharska-Orczyk I, Bonaparte JP, Morgans CW. Autoantibodies in Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy Recognize an Epitope Conserved Between TRPM1 and TRPM3. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(5):2732-2738. doi:10.1167/iovs.17-21443

- ↑ Dhingra A, Fina ME, Neinstein A, et al. Autoantibodies in Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy Target TRPM1 Cation Channels of Retinal ON Bipolar Cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31(11):3962-3967. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6007-10.2011

- ↑ Ladewig G, Reinhold U, Thirkill CE, Kerber A, Tilgen W, Pföhler C. Incidence of antiretinal antibodies in melanoma: screening of 77 serum samples from 51 patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I–IV. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(5):931-938. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06480.x

- ↑ Sarkar P, Mehtani A, Gandhi HC, Bhalla JS, Tapariya S. Paraneoplastic ocular syndrome: a pandora’s box of underlying malignancies. Eye. 2022;36(7):1355-1367. doi:10.1038/s41433-021-01676-x

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Powell SF, Dudek AZ. Treatment of melanoma-associated retinopathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12(1):54-63. doi:10.1007/s11940-009-0057-x

- ↑ Subhadra C, Dudek AZ, Rath PP, Lee MS. Improvement in Visual Fields in a Patient With Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy Treated With Intravenous Immunoglobulin. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28(1):23. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e31816754c4

- ↑ Casselman P, Jacob J, Schauwvlieghe PP. Relation between ocular paraneoplastic syndromes and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICI): review of literature. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2023;13:16. doi:10.1186/s12348-023-00338-1

- ↑ Hamdan SA, Breazzano MP, Daniels AB. Triple Therapy with Rituximab, Intravenous Immunoglobulin, and Intravitreal Corticosteroids for Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy: TTRIIC Does the Trick. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16(6):775-778. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001081

- ↑ Tian JJ, Coupland S, Karanjia R, Sadun AA. Melanoma-Associated Retinopathy 28 Years After Diagnosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(11):1276. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3500

- ↑ Maire C, Vercambre‐Darras S, Devos P, D’Herbomez M, Dubucquoi S, Mortier L. Metastatic melanoma: spontaneous occurrence of auto antibodies is a good prognosis factor in a prospective cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(1):92-96. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04364.x