Cancer Associated Retinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Cancer-associated retinopathy

Disease

Cancer associated retinopathy (CAR) is a member of a spectrum of disease called autoimmune retinopathy. [1][2] Autoimmune retinopathy is broadly separated into neoplastic and nonneoplastic.[2] CAR is a subtype of paraneoplastic syndrome and was first described by Sawyer et al. in 1976 with three cancer patients with blindness caused by diffuse retinal degeneration.[3] In CAR, retinal degeneration occurs in the presence of auto-antibodies that cross-react with tumor-tissue and retinal-tissue antigens which are recognized as foreign. In many instances, visual loss from CAR precedes the diagnosis of cancer.[4][5][6]

Etiology

Different antibodies have been isolated against many specific retinal proteins in CAR patients.[7][8] Below are some of the identified autoantibodies:

- Recoverin

- Carbonic anhydrase II

- Transducin B

- [Alpha]-enolase

- TULP1 [Tubby-like Protein 1]

- PNR photoreceptor cell-specific nuclear receptor

- Heat shock cognate protein HSC 70

- Arrestin

- Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GCAP 1 and 2 (guanylyl cyclase-activating proteins)

- Rab6A GTPase (Rab6A)

There are many more antibodies against different retinal proteins that have not yet been identified. Recoverin is a 23-kDa calcium-binding protein found on photoreceptors. Anti-recoverin antibody is the most common associated antibody observed in CAR.[8] Many different cancers have been associated with CAR. Small cell lung carcinoma, breast cancer, and gynecologic cancer are the most common cancers associated with CAR. However, CAR has been found in other types of lung cancer, colon cancer, mixed Müllerian tumor, skin squamous cancer, kidney cancer, pancreatic, lymphoma, basal cell tumor, and prostate cancer.[1][2][9][10]

Pathophysiology

Keltner et al developed an autoimmune theory in 1983 when he found antibodies against retinal photoreceptors in patients with lymphoma who developed acute vision loss and retinal degeneration.[6] Autoimmunity occurs when tumor antigens trigger an immune response from the host which creates antibodies that cross react with a retinal protein. This leads to cell apoptosis/death and retinal degeneration.[2][8]

History/Symptoms

Patients commonly present with acute/subacute painless vision loss over few weeks to months with associated positive visual phenomena (such as flashes/photopsia or flickering of lights) and photosensitivity. Symptoms tend to be bilateral but may be asymmetric and sequential, rarely unilateral. [11] Patient symptoms depend on which retinal tissue is affected as CAR can cause damage to the rods (causing nyctalopia, constricted visual fields, prolonged dark adaptation, and midperipheral (ring) scotomas) and/or cones (causing photosensitivity, reduced visual acuity, central scotomas, and decreased color perception).[1][5][10]

Symptoms may be variable depending upon the associated retinal antibody. Anti-recoverin antibody associated-CAR usually presents with acute severe vision loss and paracentral or equatorial scotoma. CAR with anti-enolase antibodies causes cone dysfunction typically leading to asymmetric central vision loss with slower progression.[12]

Physical examination

- Decreased central visual acuity

- Visual field defects (central, paracentral, or equatorial scotomas)

- Prolonged glare after light exposure

- Prolonged dark adaptation

- Afferent pupillary defect if asymmetric involvement

- Decreased color vision

- Slit-lamp and fundus can appear normal initially. With progression, clinically apparent retinal degenerations are observed (RPE thinning and mottling, attenuation of the arterioles, optic nerve pallor). Other fundus findings such as macular edema, vitreous cells, vascular sheathing, and periphlebitis have been documented.

Epidemiology

In the case series reported by Adamus involving 209 patients, women are more affected than men and the age group affected is 40 - 85 years.[13] The time interval between the diagnosis of malignancy and onset of ocular symptoms, or detection of antiretinal antibodies in serum remains variable.[2]

Clinical diagnosis

There are no set diagnostic criteria for CAR. The diagnosis is made by a combination of the patient's clinical symptoms, exam findings, diagnosis of systematic cancer, and positive antibodies against retinal proteins. Patient's visual symptoms may precede the diagnosis of systematic cancer, making the diagnosis of CAR difficult initially.

Other causes of retinal degeneration must be ruled out such as any hereditary or toxic retinal degeneration. In the absence of retinal changes, optic nerve diseases such as retrobulbar optic neuropathy, optic neuropathy related to smoking/nutritional deficiency, and hereditary optic neuropathy may need to be ruled out. Drug-related damage to the optic nerve or retina also may be considered.[1][2]

Positive anti-retinal antibodies alone do not give the diagnosis of CAR since anti-retinal antibodies can be found in the normal population and in patients with non-paraneoplastic autoimmune retinopathy.[2][14]

Diagnostic procedures

- Visual fields: central, cecocentral, or equatorial scotomas

- Fundus Angiography: is usually normal. Rarely, it could show areas of leakage if vasculitis or macular edema is present

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): loss of the outer retinal layer, including the ellipsoid layer and photoreceptors. Cystic spaces or occasionally mild schisis-like changes can be seen.[2][14]

- Electroretinogram (ERG): Full-field ERG is almost always abnormal (attenuated or absent photopic and scotopic response). In CAR where mainly the cones are affected, full-field ERG could be normal but multifocal ERG will be abnormal.[2][15]

- Fundus autofluorescence (FAF): Parafoveal ring of enhanced autofluorescence with normal autofluorescence within the ring and hypoautofluorescence outside the ring.[16]

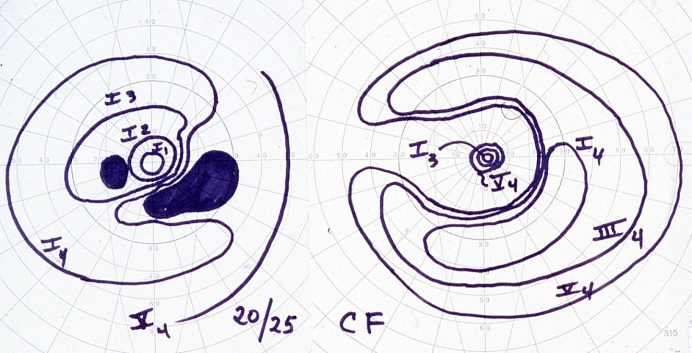

Below demonstrates a bilateral paracentral visual field defect in a CAR patient

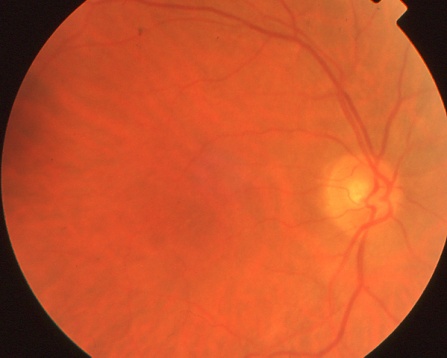

The right fundus of the same CAR patient as above appears normal.

Laboratory test

Anti-retinal antibody testing is now commercially available. (http://www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/test-catalog/Overview/57647, http://www.athenadiagnostics.com/view-full-catalog/r/recombx-trade;-car-(anti-recoverin)-autoantibody-t, http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/health/services/casey-eye/diagnostic-services/ocular-immunology-lab/, and others)

Differential diagnosis

- Retinitis Pigmentosa

- Cone Dystrophy

- Toxic Retinopathy

- Acute Zonal Outer Occult Retinopathy and other White Dot Syndromes

- Toxic-Nutritional Optic Neuropathy

- Hereditary Optic Neuropathy

- Melanoma-associated retinopathy

- Non-neoplastic autoimmune retinopathy

Management

There are no guidelines for the treatment of CAR but a high index of suspicion with early implementation of treatment may lower the risk of irreversible vision loss.[2] Long-term systemic immunosuppression is the main therapy for CAR with variable results. Local corticosteroid, systematic immunosuppressive medications (high-dose corticosteroid, cyclosporin, azathioprine, alemtuzumab), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasmapheresis, and a combination of these treatments have been utilized.[9][17][18] [19] Rituximab is starting to be used more frequently with improvement noted in case series and case reports of CAR and autoimmune retinopathy.[20][21][22] A retrospective case series evaluating rituximab with concomitant immunosuppressive agents (mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, IVIG, bortezomib, topical steroids) in 16 neoplastic and non-neoplastic autoimmune retinopathy patients (six CAR patients) demonstrated 77% of eyes achieving stable or improved vision.[20]

IVIG has been used with some success.[23] IVIG has been hypothesized to have several mechanisms of action including neutralization of autoantibodies.[14]

In patients with suspected CAR and without a history of malignancy, work-up for occult malignancy should be performed. This includes a thorough medical history and physical exam, chest x-ray/contrast enhanced computed tomogram (CT) of chest, and basic blood work (including CBC with differential and a metabolic panel). Additional testing including CT abdomen, whole body positron emission tomography (PET) scan and colonoscopy may be necessary depending on the findings of the initial work-up. In females, clinical and imaging evaluation of breast and genitourinary system is critical.[2] The treatment of systematic cancer usually does not lead to improvement of the vision.

Prognosis

The prognosis remains poor even with the above treatments.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hecklenlively JR, Ferreyra HA. Autoimmune retinopathy: A review and summary. Semin Immunopathol 2008 30:127-134

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Dutta Majumder P, Marchese A, Pichi F, Garg I, Agarwal A. An update on autoimmune retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep;68(9):1829-1837

- ↑ Sawyer RA, Selhorst JB, Zimmerman LE, Hoyt WF. Blindness caused by photoreceptor degeneration as a remote effect of cancer. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1976 81:606-613

- ↑ Hoogewoud F, Butori P, Blanche P, Brézin AP. Cancer-associated retinopathy preceding the diagnosis of cancer. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018 Nov 3;18(1):285

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Chan JW. Paraneoplastic retinopathies and optic neuropathies. Survery of Ophthalmology 2003 48(1):12-38

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Keltner JL, Roth AM, Chang S. Photoreceptor degeneration - A possible autoimmune disease. Archives of Ophthalmology 1983 101:564-569

- ↑ Hecklenlively JR, Ferreyra HA. Autoimmune retinopathy: A review and summary. Semin Immunopathol 2008 30:127-134

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Adamus G. Ren G. Weleber RG. Autoantibodies against retinal proteins in paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmology 2004 June 4;4:5

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Goldstein SM, et al.. Cancer-associated retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:1641–1645.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Raj MK, Purvin VA. Cancer associated and related autoimmune retinopathy. eMedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1227724-overview

- ↑ Almeida DR, Chin EK, Niles P, Kardon R, Sohn EH. Unilateral manifestation of autoimmune retinopathy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014 Aug;49(4):e85-7

- ↑ Weleber RG. Watzke RC. Shults WT. et al. Clinical and electrophysiologic characterization of paraneoplastic and autoimmune retinopathies associated with antienolase antibodies. Am J Ophthalmol 2005 139:780-794

- ↑ Adamus G. Autoantibody targets and their cancer relationship in the pathogenicity of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:410–414.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Grewal DS, Fishman GA, Jampol LM. Autoimmune retinopathy and antiretinal antibodies: a review. Retina. 2014;34:827–845

- ↑ Mohamed Q. Harper CA. Acute optical coherence tomographic findings in cancer-associated retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2007 125(8):1132-3

- ↑ Lima LH, et al. Hyperautofluorescent ring in autoimmune retinopathy. Retina 2012;32:1385–1394.

- ↑ Ferreyra HA. Jayasundera T. Kahn NW. et al. Management of autoimmune retinopathies with immunosuppresion. Arch Ophthalmol 2009 127(4):390-397

- ↑ Espandar L. OBrien S. Thirkill C. et al. Successful treatment of cancer-associated retinopathy with alemtuzumab. J Neurooncol 2007 83:295-302

- ↑ Guy J. Aptsiauri N. Treatment of paraneoplastic visual loss with intravenous immunoglobulin. Arch Ophthalmol 1999 117:471-477

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Davoudi S, Ebrahimiadib N, Yasa C, Sevgi DD, Roohipoor R, Papavasilieou E, Comander J, Sobrin L. Outcomes in Autoimmune Retinopathy Patients Treated With Rituximab. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017 Aug; 180():124-132.

- ↑ Boudreault K, Justus S, Sengillo JD, Schuerch K, Lee W, Cabral T, Tsang SH. Efficacy of rituximab in non-paraneoplastic autoimmune retinopathy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Jul 15; 12(1):129.

- ↑ Dy I, Chintapatla R, Preeshagul I, Becker D. Treatment of cancer-associated retinopathy with rituximab. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013 Nov;11(11):1320-4.

- ↑ Ramos-Ruperto L, Busca-Arenzana C, Boto-de Los Bueis A, Schlincker A, Arnalich-Fernández F, Robles-Marhuenda Á. Cancer-Associated Retinopathy and Treatment with Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy. A Seldom Used Approach? Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019 Nov 11:1-4.