Lacrimal Sac Papilloma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

General Considerations

Primary epithelial tumors are the most common type of neoplasm of the lacrimal sac, accounting for 73% of reported cases. Of these, papillomas appear more frequently than carcinomas. While themselves benign, papillomas are easily confused for dacryocystitis and can progress to potentially life-threatening malignancy, so it is important to carefully evaluate any potential cases.

Clinical Features

Epidemiology

Papillomas tend to develop slightly earlier than other kinds of lacrimal sac tumors, with a mean age of diagnosis of 44 years. Transitional cell papillomas, which have a mean onset age of 40, usually present earlier than squamous cell papillomas, with a mean onset age of 47. Both types have been diagnosed in patients as young as in the first decade of life. There is no demonstrated sex predilection.

Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

Lacrimal sac papillomas tend to present similarly to dacryostenosis and dacryocystitis, with almost all patients having a history of chronic epiphora that can range from several months to decades. Notably, a firm subcutaneous mass of the lacrimal sac is not always evident to palpation. If a mass is present, it is usually incompressible, non-tender, and located superior to the medial canthus. Visible extension is observed with time, though growth rate is variable.

For these reasons, lacrimal sac papillomas are often diagnosed incidentally as a result of dacryocystorhinostomy for presumed dacryostenosis. However, there are several features that can help distinguish lacrimal sac papillomas from more common forms of dacryocystitis. For instance there may be a more insidious onset of symptoms with lacrimal sac papilloma. Dacryocystotic masses are also usually compressible and rarely located superior to the medial canthal tendon. Further, dacryocystoceles may exhibit erythema, tenderness, and warmth that aren’t typically associated with papillomas.

Malignant lacrimal sac tumors can also present similarly to papillomas, but can usually be differentiated from them by the presence of hemolacria, which is rare in benign tumors. Malignant tumors tend to have a larger external mass with associated telangiectasia, and much more frequently express bloody discharge. Other signs that suggest malignancy are epistaxis, sanguineous reflux on irrigation, and submandibular or cervical lymphadenopathy.

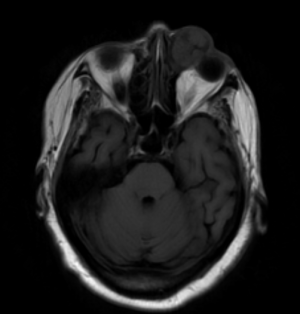

Imaging

Given the difficulties of assessing lacrimal sac papillomas with external exam, imaging studies are an important component of their diagnosis and evaluation of their extent. Smooth masses can be seen on CT or MRI, with a characteristic heterogeneous signal on the latter being useful for differentiating from more homogenous lymphoid tumors. More broadly, dacryocystography can also be used to reveal the presence and location of lacrimal sac masses like papillomas, which can show up as a characteristic protruding defect in tumors extending into the lumen, though this is not a widely used study.

Histologic Diagnosis

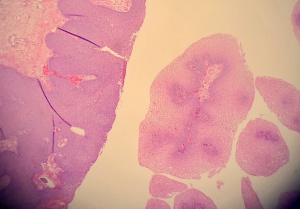

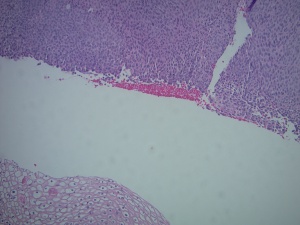

As diagnostic imaging is a poor differentiator of malignant versus benign lacrimal sac tumors, tissue biopsy is essential to confirm a diagnosis of lacrimal sac papilloma. Papillomas can be squamous, transitional (Schneiderian), or a mix of both types of epithelia, with squamous being the most common. Their growth pattern can be exophytic, with finger-like extensions of proliferating epithelium growing outward, or inverted, with endophytic growth inward toward underlying stroma. Inverted papillomas primarily occur with transitional cells and create areas of invasive acanthosis, so they are significantly more likely to progress to invasive carcinomas than exophytic papillomas. Sinonasal papillomas, also known as Schneiderian papillomas, are benign but infiltrative epithelial neoplasms that arise from ectodermally derived pseudostratified ciliated (or Schneiderian) epithelium that lines the sinonasal tract and nasal cavity.

Characteristic findings of squamous papillomas include acanthotic, stratified squamous epithelium, with an inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells and neutrophils often present in the underlying stroma. Inflammatory cells can also be found within the endothelium itself, which can variably exhibit abnormalities such as vacuolization and dyskeratosis. Transitional cell papillomas often have a similar inflammatory stromal infiltrate, but are uniquely marked by the presence of scattered goblet cells in some lesions.

Notably, each type of papilloma exhibits a relative uniformity of cell types. This helps distinguish them from malignant tumor forms, which demonstrate irregular epithelium, prominent mitotic figures, and invasion through the basement membrane into underlying stroma. A high degree of cell dysplasia in a biopsy otherwise consistent with a papilloma versus a carcinoma suggests a transformation toward malignancy.

Of note, HPV has been associated with the majority of lacrimal sac papillomas, with types 6 and 11 specifically being correlated to squamous papillomas. In Situ Hybridization (ISH) and PCR can be used to detect HPV DNA and RNA in tumor biopsies to confirm this etiology.

Management

Treatment

Because of the malignant potential of lacrimal sac papillomas, they should not be managed as completely benign lesions. The best opportunity for successful control of the papilloma is surgical excision of the lesion in its entirety via a dacryocytotomy or dacryocystectomy with or without a lateral rhinotomy and removal of the lacrimal duct if extensive. Care should be taken not to disturb the lacrimal fossa, which could spread pre-malignant cells into the sinuses. Tumor-free margins can be verified by intraoperative frozen section analysis. Mitomycin C has been recommended as adjunctive therapy for treatment of inverted (Schneiderian) papilloma of the lacrimal sac. [1]

For masses confirmed by biopsy to be non-malignant papillomas, dacryocystectomy is not usually indicated. Similarly, radiation is not indicated as an adjunct to surgery provided that there’s been no observed evolution to invasive carcinoma, though radiation may be considered a deterrent to future recurrence.

Prognosis

Despite a good overall prognosis for benign lacrimal sac papillomas, outlook can be severely complicated by malignant change. Case studies have shown that up to half of inverted papillomas may develop into invasive carcinomas if allowed to progress untreated. Carcinomas, which can also develop de novo, have a wide mortality rate ranging from 13.6% for papillary squamous carcinomas to 100% in transitional cell carcinomas.

Recurrence, which occurs in 40-60% of cases of sinonasal papillomas, is also a significant clinical problem. Recurrence generally occurs at the same location as the previously excised tumor, so these anatomical sites should be carefully monitored post-surgery for signs of return. Recurrent lacrimal tumors may also reappear posteriorly into the cranium, further complicating future surgical treatment. Radiation therapy can reduce the risk of recurrence, though this must be balanced with associated risks such as damage to normal structures and secondary malignancy.

References

- ↑ Woodcock M, Mollan SP, Harrison D, Taylor D, Lecuona K., Mitomycin C in the treatment of Schneiderian ( inverted) papilloma of the lacrimal sac, Int Ophthalmol. 2010 Jun;30(3):303-5. doi: 10.1007/s10792-009-9314-y. Epub 2009 Jul 23.

- Stefanyszyn MA, Hidayat AA, Pe’er JJ, Flanagan JC. “Lacrimal sac tumors.” Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr Surg. 1994; 10: 169-84.

- Parmar DN and Rose GE. “Management of lacrimal sac tumours.” Eye Nature. 2003; 17:599-606.

- Kim HJ, Shields CL, Langer PD. “Lacrimal sac tumors: diagnosis and treatment.” Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011; 609-14.

- Hornblass A, Jakobiec FA, Bosniak S, Flanagan J. “The diagnosis and management of epithelial tumors of the lacrimal sac.” Ophthalmology. 1980; 87: 476-90.

- Sjo NC, von Buchwald C, et al. “Human papillomavirus: cause of epithelial lacrimal sac neoplasia?” Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007; 85: 551-6.

- Tarjani VD, Dilip M, Mittal R, Mohammad JA. “Accidentally diagnosed transitional cell papilloma of the lacrimal sac.” Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017; 31: 177-79.

- Ni C, D’Amico DJ, Fan CQ, Kuo PK. “Tumors of the lacrimal sac: a clinicopathological analysis of 82 cases.” International Ophthalmology Clinics. 1982; 22: 121-40.

- Jang JH, Chang SD, Choe MS. “A case of recurrent Schneiderian Papilloma of the Lacrimal Sac Invading the Nasal Cavity.” Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009; 23: 100-103.

- Flanagan JC. “Lacrimal Sac Tumors.” Amer Acad Ophthal. 1978; 85: 1282-1287.

- Hyams VJ. "Papillomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses." A clinicopathological study of 315 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1971;80:192–206

- Ryan SJ, Font RL. "Primary epithelial neoplasms of the lacrimal sac." Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76:73–88