All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Goldenhar syndrome. ICD-10: Q87.0

Disease

Also called as facio-auriculo-vertebral dysplasia, unilateral craniofacial microsomia, first and second branchial arch syndrome, lateral facial dysplasia, otomandibular dysostosis, velocardiofacial syndrome, and unilateral mandibulofacial dysostosis.[2][3] Goldenhar syndrome (GS) is characterized by craniofacial anomalies in association with vertebral, cardiac, renal, and central nervous system defects. The syndrome is characterized by a triad of anomalies comprising epibulbar dermoid, accessory auricular appendages, and aural fistula.[4]

History Of Disease

- 1861- Classical features were first seen by Canton and then two decades later by Von Arlt.[5]

- 1952- Goldenhar recorded Hemifacial microsomia which included oral, aural, and mandibular developmental defects and epibulbar dermoids.[5]

- 1963- Gorlin et al. suggested the name oculo-auriculo-vertebral (OAV) dysplasia to include vertebral anomalies.[5]

- 1978- Smith used the term facio-auriculo-vertebral sequence to include both hemifacial microsomia and Goldenhar syndrome.[5]

Etiopathogenesis

Various hypothesis has been put forwarded to explain etiopathogenesis.[3][6] Gorlin and Pindborg suggested that an unknown primary cause of faulty embryological development causes abnormality of the mesoblasts giving rise to branchial and vertebral anomalies. Jong Bloet hypothesized that the syndrome was a result of fertilization of overripe or aged ovum. Currently accepted theory states that the syndrome occurs due to imbalance in cells during the blastogenesis period (30-45 days of intrauterine life) of embryo formation. It is found to involve the derivatives of first and second branchial arches. The condition is apparent at birth, but the phenotype can vary greatly in its severity depending on the activation and expression of the defective gene.

Risk Factors

Multifactorial etiology has been proposed where nutritional and environmental factors along with genetic dysregulation have been projected as the causative factors.[5]

- Drugs: Thalidomide, Cocaine, Retinoic acid, Tamoxifen, Anticoagulants (result in hematoma in the region of the developing ear and jaw which causes destruction of the differentiating tissue leading to branchial arch dysplasia)

- Maternal diabetes

- Multiple gestations

- bleeding in the second trimester

- Malnutrition

- Exposure to tobacco during pregnancy

- Chromosomal aberrations such as 3del(5p), del(6q), del(8q)(161), del(18q), del(22q), recombinant chromosome 18, ring 21 chromosome, and dup(22q)

- Maternal and fetal hypoxia

- Hypertension

- Radiodiagnostic procedures such as cholecystography practiced between the 4th and 6th week of gestation.

- Consanguineous marriage

Epidemiology

Prevalence ranging from 1:3,500 to 1:7,000 live births.[3] Male-female ratio of 3:2. Although most cases are sporadic, familial occurrences (autosomal dominant) have been observed. An empiric sibling recurrence of 2%–3% is reported .Usually, it is unilateral and has a right-side predominance.[7]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of Goldenhar syndrome is primary clinical, based on history and examination of the eye, face and skeletal system.

History

The classic history for Goldenhar syndrome will be a child, more commonly a boy, in the first decade of life with symptoms of mass on bulbar conjunctiva and poor hearing.

Physical examination

Diagnosis is based on clinical features. General features include unilateral facial asymmetry. There are certain clinical findings which are typical to GS:[8]

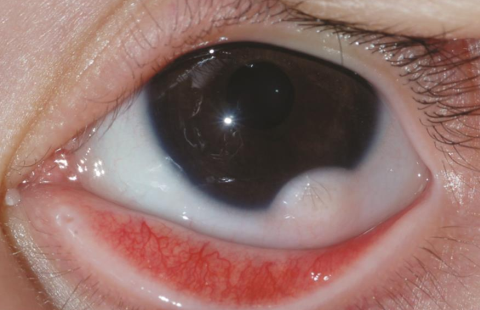

Eyes: Microphthalmia, epibulbar dermoids / limbal dermoids, lipodermoids, and coloboma are common manifestations.

Epibulbar dermoids occur in about 35% of cases. These may be unilateral or bilateral. They appear as solid yellowish or pinkish white ovoid masses which vary in size from that of a pinhead to 8–10 mm in diameter. They usually occur at the inferotemporal quadrant at the limbus. The surface is usually smooth and frequently has fine hairs. They can occur at any location on the globe or in the orbit and can be dermoid or dermis like or complex.

Coloboma may be in form of eyelid coloboma, coloboma of iris or choroid. Eyelid colobomas can be in the upper or lower eyelid, but most commonly in the upper eyelid, resulting in significant lagophthalmos or ocular surface exposure.

Other ocular features such as strabismus, Duane retraction syndrome, epicanthal folds, anophthalmia, anomalies of lacrimal drainage system, retina and optic nerve anomalies, glaucoma have also been reported.[9][10][11]

Ear: Anotia to an ill-defined mass of tissue that is displaced anteriorly and inferiorly to a mildly dysmorphic ear may be seen. Supernumerary ear tags, unilateral and bilateral preauricular tags of skin and cartilage, along with blind fistulas and sinuses, are extremely common. Isolated microtia is considered a microform of OAV spectrum.

Face: Marked facial asymmetry with unilateral macrostomia may be seen due to displacement and abnormality of the pinna and other underlying abnormalities of the skeleton. Aplasia or hypoplasia of the mandibular ramus and condyle may be seen. This in turn may lead to reduction in the size of maxillary, temporal, and malar bones. Hypoplasia of the zygomatic area may also be seen.

Skeletal alterations: Defects of the skull such as cranium bifidum, microcephaly, dolichocephaly, and plagiocephaly have been noted. Spina bifida, hemivertebrae, butterfly, fused, and hypoplastic vertebrae like vertebral anomalies have been seen. Other systems: Anomalies affecting trachea, lung, heart, kidney, and gastrointestinal systems may also be associated.

Diagnostic procedures

The diagnosis of Goldenhar syndrome is clinical, however, there are some diagnostic tests that can be helpful. Prenatal ultrasonic diagnosis may theoretically be done at the 11th–15th week in utero.[6] Newer imaging modalities such as three-dimensional ultrasound may help in detection of microtia, preauricular tags, and asymmetry of the mandible even in mild forms. Most cases of Goldenhar syndrome occur de novo, but an autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance has also been noted. A three-generation family history has to be determined looking for cases as mild as ear tags or ear pits. Although there is not yet a specific genetic test to detect Goldenhar syndrome, array comparative genomic hybridization should be considered while testing for a possibility of recurrence.

Differential diagnosis

- Treacher–Collins syndrome usually shows similar features with a bilateral presentation.

- Townes–Brocks syndrome shows additional thumb anomalies, anal defects, and renal anomalies which are not seen in GS.

- Linear nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn shows additional features of cloudy cornea, warty cutaneous lesions, infantile spasms.

- CHARGE syndrome is associated with characteristic semilunar canal anomalies and cranial nerve dysfunctions while mandibulofacial dysostosis can be differentiated by esophageal atresia and microcephaly.

Management

General Protocol

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary for the overall well-being of the patient and the treatment protocol should be determined as early in the life as possible to avoid physical difficulty and psychological stigma to the growing child. Pediatric specialists along with ear-nose-throat, orthopedics, neurosurgeons, orthodontists and maxillofacial surgeons and ophthalmologists to decide on the most appropriate treatment plan, which varies with age and systemic associations.

Eyelid reconstruction may be necessary at any stage if significant coloboma results in exposure keratopathy and risk of visual compromise.

Treatment of an individual with Goldenhar syndrome depends on the severity of the phenotype and the age at which treatment is instituted.

Newborns-2 years of age

They should be assessed for difficulties in breathing, feeding, and sleeping.

Toddlers of 2–4 years age

Those with severe mandibular hypoplasia should be treated with costochondral grafts and osteodistraction devices while those with mild deformities can undergo surgical correction at a later stage.

Young children of 6–8 years

They are prime candidates for correction of the external ear deformities.

Teenagers

Offers the advantage that the patient's facial structures are fully grown and the patient can tolerate intermaxillary fixation following correction of jaw deformities. Therefore, correction of these defects in mild forms is postponed until the child reaches the completion of growth phase. In the meantime, problems with speech, hearing, and other organ deficits should be addressed.

Ocular management

The ocular dermoids are benign tumors but may lead to serious ophthalmic consequences like induced astigmatism, amblyopia and strabismus. The epibulbar lipodermoids and dermoids of large size may obstruct the visual axis, cause limitation of ocular motility or hinder eyelid closure leading to exposure keratitis and corneal ulceration. The dermoid with lashes may cause constant rubbing of eye leading to symptoms of irritation, watering, discharge, secondary infections and corneal epithelial defects and ulcerations. The early diagnosis and surgical excision of limbal dermoid lesions may prevent amblyopia and strabismus especially in pediatric age group.

Eyelid reconstruction of a coloboma may often be challenging due to the small facial structures and limited movement of surrounding soft tissues. Eyelid-sharing techniques for eyelid margin reconstruction are often not ideal due to risk of occlusion amblyopia.

Surgery

Reconstructive surgery can be performed for structural deformities of the eyes and ear.

Stem cell grafting (womb tissue grafting) has been successfully used to "reprogram" eye dermoids, effectively halting the regrowth of eye dermoids.

Reconstructions can be done using rib bone grafts in patients with hypoplastic mandible. Bone distraction and osteogenesis may be used to lengthen the underdeveloped maxilla. In cases with cleft lip and palate, surgical corrections can be done followed by orthodontic correction on completion of jaw growth.

Prognosis

The prognosis for this condition is good in patients with no systemic complications.[8] Management of Goldenhar syndrome a requires long-term commitment with treatment spanning the child's period of growth and development.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Goldenhar-Gorlin syndrome. https://www.aao.org/image/goldenhar-gorlin-syndrome Accessed July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Gorlin RJ, Cohen MM, Hennekam RC. Syndromes of the Head and Neck. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kokavec R. Goldenhar syndrome with various clinical manifestations. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2006;43:628-34.

- ↑ Bekibele CO, Ademola SA, Amanor-Boadu SD, Akang EE, Ojemakinde KO. Goldenhar syndrome: A case report and literature review. West Afr J Med 2005;24:77-80.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Madiyal A, Babu SG, Ajila V, Madi M, Bhat S. Goldenhar syndrome: Report of two cases with review of literature. CHRISMED J Health Res 2018;5:67-71.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sinha S, Singh AK, Mehra A, Singh R. Goldenhar syndrome – A literature review. JSM Dent 2015;3:1052-5.

- ↑ Ashokan CS, Sreenivasan A, Saraswathy GK. Goldenhar syndrome – Review with case series. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:ZD17-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Achalli S, Babu SG, Patla M, Madi M, Shetty SR. Goldenhar syndrome: A case report and review. CHRISMED J Health Res 2017;4:150-4

- ↑ S. Bhallil, I. Benatiya, O. El Abdouni, B. Mahjoubi, and T. Hicham. Goldenhar syndrome: ocular features. Bull. Soc. belge Ophtalmol. 2010; 316, 17-20

- ↑ Sharma JK, Pippal SK, Raghuvanshi SK – Goldenhar Gorlin’s syndrome. case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;58: 97-101

- ↑ Rao VA, Kaliaperumal S, Subramanyan T, Rao KR, Bhargavan R. Goldenhar's sequence with associated juvenile glaucoma in Turner's syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol 2005;53:267-8