Focal Scleral Nodule

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Focal scleral nodules were originally given the name unifocal helioid choroiditis when they were first described in 1996. With the advent of optical coherence tomography, it was discovered that these lesions in fact originate within the sclera, thus leading to our current nomenclature of focal scleral nodule.

These benign lesions are characteristically yellow or white, minimally elevated, round and postequatorial. Their appearance may be concerning for choroidal melanoma or metastasis but can be distinguished from those lesions by careful clinical exam and optical coherence tomography. They are rarely visually significant and usually do not require any intervention.

Condition Entity

A focal scleral nodule (FSN) is a yellow-white, elevated, round, non neoplastic lesion arising from the sclera and classically located posterior to the equator.

Condition History

Prior to the advent of OCT, FSN as a clinical entity was difficult to distinguish from other choroidal lesions such as unifocal helioid choroiditis. The latter was first described by Hong et al in 1996.[1] Later, Shields et al published a study of 60 lesions and termed the condition solitary idiopathic choroiditis because their clinical appearance resembled that of a quiescent choroidal granuloma (though without evidence of systemic granulomatous disease).[2] With the development of enhanced depth imaging OCT, these lesions were further investigated and some were found to originate within the sclera rather than the choroid.[3] In 2020, Fung et al published a retrospective observational study of 63 patients with similar findings and coined the term focal scleral nodule based on the absence of choroiditis and origin within the sclera.[4]

Epidemiology

To date there is limited data on the prevalence of FSN. Studies have shown a wide range of presenting ages with patients as young as three and as old as eighty-three. There is some evidence that it may be more common in females and Caucasians. [2][4]

Risk Factors

Risk factors remain poorly understood likely due to the poor understanding of the pathogenesis. Several associations have been suggested including associations with systemic diseases such tuberculosis, syphilis, sarcoidosis, cat scratch disease and coxsackie virus. [5][6] However, this remains unclear and has been challenged in recent literature; no significant relation with these systemic conditions has been found.[4]

General Pathology

The pathology of FSN lesions is poorly understood and will require future investigation. One theory is that it may be a congenital condition that may develop prior to birth as evidenced by its occurrence in some young individuals.[4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made clinically based on physical examination and imaging.

Physical examination

FSN classically presents as an elevated yellow or yellow-white subretinal lesion. It is frequently accompanied by a surrounding orange halo. Retinal pigment epithelial changes are variable and may demonstrate atrophy. Nearly all lesions will be postequatorial and are most commonly noted near the optic nerve. They have been shown to generally have a size of approximately one disc diameter.[4] The majority are inactive and have well defined borders. However, some may appear active with associated inflammation, subretinal fluid and poorly defined borders.

Imaging Features

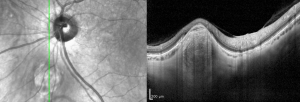

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) has led to new understanding of FSN including the anatomic origin within the sclera (instead of the choroid as previously described). Most lesions have a dome-shaped contour, but nodular or volcanic shapes have also been noted. The overlying choroid is displaced and compressed against Bruch's membrane. The resulting thinning or absence of the overlying choroid is the likely cause of their yellow-white, atrophic appearance on fundoscopic exam. OCT angiography will show the lesions to be avascular and most will demonstrate hyperautofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging.[4]

Signs and Symptoms

Effects on vision are variable with the majority being asymptomatic. In patients with symptoms, the most common were floaters or blurry vision in the affected eye.[4] Some of the visual complaints may also be related to the lesion’s relationship to the macula as it may induce abnormal architecture in the macula and fovea.

Differential diagnosis

Many lesions have a somewhat similar presentation to FSN. Some of which are benign while others are may indicate a more urgent or dangerous disease. A thorough exam and imaging are important to differentiate these lesions and many can be ruled out with OCT showing a scleral lesion vs a lesion arising from the choroid. [4]

The following lesions may present similarly:

- Choroidal metastasis

- Choroidal melanoma

- Choroidal lymphoma

- Retinoblastoma

- Astrocytic hamartoma

- Choroidal nevus

- Choroidal granuloma

- Choroidal scars

- White dot syndromes

- Sarcoidosis

- Ocular tuberculosis

- Ocular syphilis

- Fungal chorioretinitis

- Sclerchoroidal calcification

Of note, a FSN may easily be mistaken for sclerochoroidal calcification which also arises from the sclera as shown on OCT. Furthermore, it may present with similar thinning of the overlying choroid. However, sclerochoroidal calcifications are often more peripheral compared to FSN lesions. They also demonstrate more irregular shapes compared to the characteristically round FSN lesion.[4] Bscan is most useful in differentiating these two entities as it will reveal hyper-echogenicity within the area of calcification not otherwise present with FSN.

Clinical Course

When followed over time most FSN lesions remain stable without changes. Nevertheless, there are reports of lesions that demonstrate growth or resolution with long-term follow-up.[4]

Management

Due to the benign nature and limited functional impact of a FSN, no treatment is indicated in most cases. In the event that a lesion does appear to be active with associated inflammation, systemic steroids have been suggested as a possible trial treatment though there is little evidence to demonstrate their efficacy.[4] Active lesions may respond favorably with or without steroid treatment. [2]

The most important aspect of management is to correctly rule out similarly appearing lesions (such as amelanotic choroidal melanoma or choroidal metastasis) which may otherwise present a serious threat with regard to both vision and mortality.

References

- ↑ Hong PH, Jampol LM, Dodwell DG, Hrisomalos NF, Lyon AT. Unifocal helioid choroiditis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997 Aug;115(8):1007-13.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Shields JA, Shields CL, Demirci H, Hanovar S. Solitary Idiopathic Choroiditis: The Richard B. Weaver Lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(3):311–319.

- ↑ Fung AT, Kaliki S, Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Solitary idiopathic choroiditis: findings on enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in 10 cases. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:852–858

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Fung AT, Waldstein SM, Gal-Or O, Pellegrini M, Preziosa C, Shields JA, Welch RJ, Dolz-Marco R, Sarraf D, Nagiel A, Lalane R, Jung JJ, Ghazi NG, Ramtohul P, Arnold JJ, Sakurada Y, Choudhry N, Balaratnasingam C, Freund KB, Shields CL. Focal Scleral Nodule: A New Name for Solitary Idiopathic Choroiditis and Unifocal Helioid Choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2020 Nov;127(11):1567-1577.

- ↑ Goyal S, Ware GT, Petrovic' V. Coxsackie virus a possible missing link to unifocal helioid choroiditis? Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015 May-Jun;43(4):377-9.

- ↑ Kumar V, Khoo CT, Shields CL. Solitary idiopathic choroiditis in the setting of extensive animal exposure. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2016 Fall;10(4):386-8.