Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (TTS)

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS), also known as trigeminal neurotrophic ulceration, is a rare facial ulceration syndrome that can develop after central or peripheral injury to the trigeminal nerve. The syndrome was first observed and documented by neurosurgeons in the early 1900s after performing trigeminal rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia.[1] The classic triad of TTS includes paresthesia, anesthesia, and ulceration along the distribution of the trigeminal dermatome(s). Despite identification of this disorder more than a century ago, there are few reports detailing the ocular sequelae of TTS in the current literature.

Anatomy

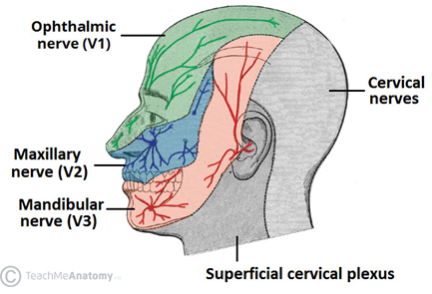

The trigeminal nerve is the fifth cranial nerve (CN V). It originates in the pons and travels from the brainstem to Meckel’s cave within the middle cranial fossa. Meckel’s cave is located immediately lateral to the cavernous sinus in a depression of the temporal bone, and it is here where the trigeminal ganglion is located. The trigeminal ganglion gives rise to the three major peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve: the ophthalmic branch (V1), the maxillary branch (V2), and the mandibular branch (V3).

The ophthalmic branch (V1) exits the cranium via the superior orbital fissure to provide sensory innervation to the upper portion of the face, which includes the scalp and forehead, the upper eyelids, the ocular surface (including the conjunctiva and the cornea), and part of the nose (including the tip of the nose). The corneal reflex is mediated by afferent input from V1 and efferent input via the facial nerve to the orbicularis oculi muscle.

The maxillary branch (V2) exits via the foramen rotundum to provide sensory innervation to the middle portion of the face, which includes the lower eyelids, midface and cheek, the ala of the nose and nares, the nasal mucosa, and the upper lip, upper teeth, and gums.

The mandibular branch (V3) exits the cranium through the foramen ovale and is responsible for sensory innervation to the lower face, including the lower lip, lower teeth and gums, chin, majority of the jaw, and portions of the external ear. V3 also provides autonomic innervation, as well as motor components that innervate the muscles of mastication, which include the masseter, temporal muscle, and medial and lateral pterygoids. Additionally, the tensor veli palatini, the mylohyoid, the anterior belly of the digastric, and the tensor tympani also gain motor innervation from V3.

It is important to note that dermatomal areas supplied by the branches of the trigeminal nerve have sharply demarcated borders (Figure 1). TTS most commonly arises at the junction between the V1 and V2 distributions at the ala nasi.[2]

Epidemiology & Risk Factors

TTS has a strong female predominance with the age of affected patients ranging from 14 months to 94 years with a mean of 57 years.[2][3][4][5][6][7] Disease onset after trigeminal insult varies from weeks to decades with a median onset of one year.[2] The largest risk factor for development of TTS is damage to the trigeminal nerve. The most common causes of nerve injury are iatrogenic via surgery (e.g., for trigeminal neuralgia) and ischemic damage. Other reported causes of nerve injury include herpes zoster virus, acoustic neuroma, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, posterior fossa tumors, and postencephalitic injury.[6][7] Ocular sequelae of TTS have been observed after trigeminal nerve injury secondary to ablation, nerve resection, brain tumor resection, compressive neuropathy, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, and cerebrovascular ischemia.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16] One patient also developed disease after a head injury despite MRI showing no gross injury to the trigeminal nerve or its branches at the time.[7] Ocular complications of TTS are believed to stem from trauma secondary to corneal anesthesia rather than directly from resection of the trigeminal sensory root.[17]

After initial nerve damage, patients with compulsory picking behaviors or behavioral disinhibition (i.e., dementia, psychiatric disorders) are at highest risk for developing TTS.[2]

Pathophysiology

Most TTS cases result after iatrogenic injury to the trigeminal nerve. Regardless of the inciting event, it is believed that trigeminal nerve injury results in decreased sensation in the distribution of the affected branch that encourages self-manipulation of the tissue in certain patients. This mechanism of trauma leads to persistent skin ulceration and, in extreme cases, frank tissue loss.[2][6] Ulcerations can occur anywhere along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, most commonly in the V2 distribution. It is important to recall that the tip of the nose is specifically innervated by the ethmoidal branch of the distal V1 and is therefore spared in many TTS cases.[6]

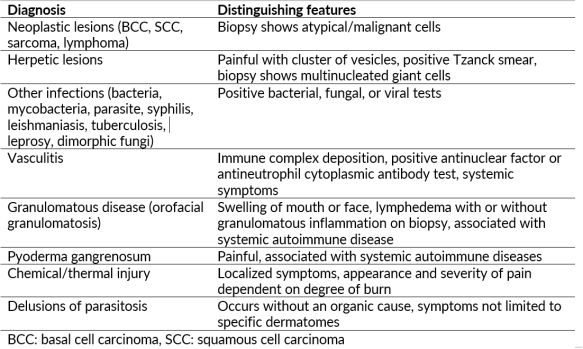

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for facial ulceration is broad. While TTS is a diagnosis of exclusion, it can be caused by undiagnosed life-threatening and/or treatable pathologies; thus, a thorough history and physical exam are essential when evaluating these patients.

Clinical Evaluation & Diagnosis

TTS is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion and should be suspected in a patient presenting with paresthesia and facial ulceration with a medical history likely including a prior trigeminal nerve insult.

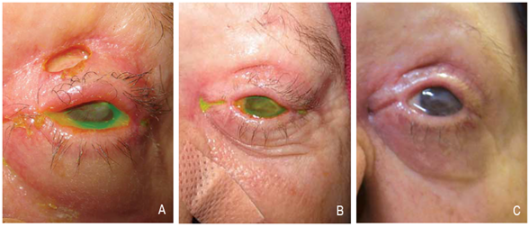

Ulcerations may be one large confluent patch or appear in clusters (Figure 2). The classic lesion appears at the nasal ala. The upper lip is also commonly affected, and soft tissue scarring can draw the upper lip into a characteristic sneer (Figure 3). Other sites of ulceration reported in the literature include the cheek, forehead, scalp, ear, jaw, and palate.[1] Periocular manifestations include eyelid or canthal lesions which can cause secondary ectropion, lagophthalmos, full-thickness lid defects, and even secondary orbital cellulitis.[7][9][17] Corneal ulcers can be present secondary to exposure keratopathy or neurotrophic keratitis.[18] Facial ulcers are extremely persistent once they appear.[6]

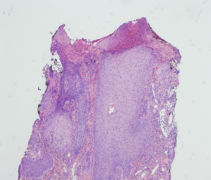

Samples of the involved tissue should be collected and evaluated with Gram stain, viral and fungal elements, and cultured for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal disease. Biopsy with histopathologic evaluation is required to rule out other diagnoses. Histology reveals non-specific inflammatory changes, most notably ulceration with adjacent lichenification and epidermal and dermal scarring with mild mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 4).[4] Acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis are also common.[13] Laboratory work-up is typically unremarkable but could be undertaken if the diagnosis remains unclear after biopsy and should include infectious, autoimmune, and vasculitis labs. Neuroimaging is recommended if the underlying cause of TTS is unclear from the patient’s history.[2]

Management

TTS and its ocular manifestations require multidisciplinary management that can involve psychiatry, dermatology, neurology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery.

Behavioral Therapy

Since persistent digital manipulation of the hypoaesthetic tissues is a key factor in development or perpetuation of the facial ulceration, the standard approach to TTS cases must involve behavioral modification followed by possible medical or surgical management. Physicians should recommend that patients keep their nails short and limit hand movement to the area of disease involvement. If necessary, glove or arm splinting at night can reduce manual manipulation. Disease prognosis is strongly dependent on the patient’s ability to modify this behavior.[2]

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy includes pharmacologics aimed at behavior modification as well as topical medications to protect and heal any affected tissues. The most common medications used to modify behavior include systemic neuromodulating agents like gabapentin and carbamazepine.[2][19] Other medications that have been trialed include amitriptyline, pimozide, diazepam, tiagabine, and oxcarbazepine with varying degrees of success.[2][20][21]

Wounds with secondary infection should be treated with topical or systemic antibiotics as indicated by the severity of the infection. However, it is unclear if skin ulceration alone requires topical therapies: emollients and topical steroids have been reportedly unsuccessful and may possibly delay wound healing.[2]

There may be a role for topical immunosuppression. One study saw improvement of ulcers with gabapentin 200 mg twice daily and topical tacrolimus ointment.[22]

Patients with periocular involvement are susceptible to neurotrophic keratitis. If ocular involvement develops, patients should be diligent in keeping the affected eye lubricated with lubricating drops and ointments. Preservative-free formulations are preferred to prevent chemical toxicity to the eye. Other non-surgical treatment options for neurotrophic keratitis include punctal plugs and bandage contact lenses.[12] Patients who develop secondary infectious keratitis should be managed with appropriate anti-infective therapies.

Surgical Therapy

Patients who have documented success in restraining from manual manipulation may benefit from surgery.[2] For patients where surgery may be indicated, ocular surface involvement may necessitate amniotic membrane transplantation and/or tarsorrhaphy.[8][11][12] Keratoplasty was recommended in one published case but was ultimately not performed due to lack of follow up by the patient.[14] Eyelid and/or facial reconstruction may be beneficial in the long term. Skin grafts and flaps have had some success (Figure 5),[17] though there is insufficient data to determine whether neurotized or non-neurotized flaps are most optimal.[7][8][23] Different types of flaps used for facial reconstruction are beyond the scope of this article and often require involvement of plastic surgery or otolaryngology colleagues.

Other Treatment Options

Transcutaneous nerve stimulation has been utilized with limited success in TTS; unfortunately, relapse is common after discontinuation of treatment.[24] Negative pressure therapy, vacuum assisted wound closure, and thermoplastic face masks may promote wound healing while limiting digital manipulation.[25][26][27] There is one report of an in vitro cultured epidermal cell transplant with excellent short-term cosmetic results.[28] However, the authors admit that the exact regeneration mechanism after this experimental treatment was unclear, warranting further histopathological analysis.[28]

Summary

Trigeminal trophic syndrome is a rare ulcerative syndrome that follows trigeminal nerve injury, most commonly after surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia or ischemic stroke. Reduced sensation in the trigeminal nerve distribution leads to persistent digital manipulation and the development of ulcerations, classically in the V2 dermatome. Ocular involvement has been reported involving the cornea, eyelid, and canthal structures. Behavior is strongly associated with disease prognosis ; thus, treatment is primarily aimed at behavior modifications that would reduce or eliminate manual manipulation. Both medical and surgical therapies have variable success.

Additional Resources

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Oaklander AL. Common neuropathic itch syndromes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(2):118-125. doi:10.2340/00015555-1318

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: An updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2018;58(5):530-537. doi:10.1111/ijd.14098

- ↑ Pazhaniappan N. "The Trigeminal Nerve (CN V)". TeachMeAnatomy. August 15, 2020. Accessed August 6, 2022. https://teachmeanatomy.binfo/head/cranial-nerves/trigeminal-nerve/

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Garza I. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of face pain, dysaesthesias, anaesthesia and skin/soft tissue lesions. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(9):980-985. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01636.x

- ↑ Kumar P, Thomas J. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):75-76. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.123506

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Rashid RM, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(6):725-731. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02250.x

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome-report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(5):807-812. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30220.x

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Nemet AY. Full-thickness eyelid defect in a trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(10):1438. doi:10.1001/archopht.125.10.1438

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Thompson L, Powell S. Trigeminal trophic syndrome leading to orbital cellulitis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2018;2(2):121-124. doi:10.5811/cpcem.2018.1.36622

- ↑ Malecha MA, Haddox C, Mitra AK. Neurotrophic Keratopathy Associated with Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(13):3586.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 McVeigh KA, Adams M, Harrad R, Ford R. Periocular manifestations of trigeminal trophic syndrome: A case series and literature review. Orbit. 2017;37(1):32-35. doi:10.1080/01676830.2017.1353117

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Lam BC, Saboo US, Kheirkhah A. Acute neurotrophic keratitis with trigeminal trophic syndrome after craniotomy. J AAPOS. 2020;24(6):376-379. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.07.011

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Kovacs KD, Ehrlich MS. Cicatricial eyelid paralysis secondary to trigeminal trophic syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3). doi:10.1097/iop.0000000000000766

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Uysal PI, Artuz RF, Yalcin BA. A rare case of trigeminal trophic syndrome with an extensive scalp, forehead, and upper eyelid ulceration in a patient with undiagnosed Alzheimer disease. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21(8). doi:10.5070/d3218028437

- ↑ Güngör-Doğan İ, Sarıkaya-Solak S. Trigeminal trophic syndrome and neurotrophic keratopathy following stroke. Neurol Sci Neurophysiol. 2020;37(4):231. doi:10.4103/nsn.nsn_96_20

- ↑ Karadan U, Manappallil RG, Janardhanan A, Supreeth RN. Trigeminal trophic syndrome following anterior inferior cerebellar artery infarction. BMJ Case Rep. 2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-225278

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 McKenzie KG. OBSERVATIONS ON THE RESULTS OF THE OPERATIVE TREATMENT OF TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA. Can Med Assoc J. 1933;29(5):492-496.

- ↑ Lane JE, Deliduka S. Self-induced nasal ulceration from trigeminal trophic syndrome. Cutis. 2008;81(5):419-420.

- ↑ Upshaw WN, Bilyeu CW. Carbamazepine as a Treatment for Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Review. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(5):580-582. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2015.05.004

- ↑ Mayer RD, Smith NP. Improvement of trigeminal neurotrophic ulceration with pimozide in a cognitively impaired elderly woman--a case report. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18(2):171-173. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb01007.x

- ↑ Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115(9):1118. doi:10.1001/archderm.1979.04010090060029

- ↑ Nakamizo S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Treatment of neuropathic itch possibly due to trigeminal trophic syndrome with 0.1% topical tacrolimus and gabapentin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(6):654-655. doi:10.2340/00015555-0953

- ↑ Tollefson TT, Kriet JD, Wang TD, Cook TA. Self-induced nasal ulceration. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(3):162-166. doi:10.1001/archfaci.6.3.162

- ↑ Westerhof W, Bos JD. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: a successful treatment with transcutaneous electrical stimulation. Br J Dermatol. 1983;108(5):601-604. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb01063.x

- ↑ Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(8):984-986. doi:10.1001/archderm.144.8.984

- ↑ Swan MC, Downie IP, Horlock N. Management of trigeminal trophic syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(3):1124-1126. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819a33ca

- ↑ Kurien AM, Damian DL, Moloney FJ. Trigeminal trophic syndrome treated with thermoplastic occlusion. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52(1):e1-e4. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2009.00613.x

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Schwerdtner O, Damaskos T, Kage A, et al. Autologous epidermal cells can induce wound closure of neurotrophic ulceration caused by trigeminal trophic syndrome. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 34: 443–445.