Temporal Artery Biopsy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Diagnostic Intervention

Description/Overview

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic vasculitis involving the large and medium-sized arteries of the cranial arteries, [1] coronary arteries, [2] common and internal carotid arteries, aorta, [3] and extracranial arteries.[4]. The diagnosis of GCA is made on the basis of symptoms, clinical findings, and laboratory results (ESR and CRP). Biopsy of the temporal artery is considered the gold standard to confirm GCA.[4] A positive biopsy result confirms the diagnosis and justifies long-term steroid use in patients with a high chance of immunosuppressive related morbidity.[5]

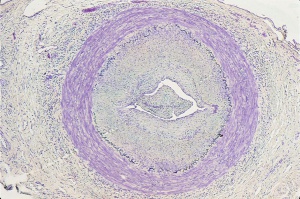

Histopathology

Typical histopathological interpretations of blood vessel biopsies include active arteritis, healed arteritis, arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis, or normal. Changes in active temporal arteritis include granulomatous inflammation, presence of giant cells, destruction of elastic fibers, splitting and fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina, deposition of calcium salts into the area of the internal elastic lamina, diffuse inflammation of the vessel wall, and ingrowth of capillaries.[6] Healed arteritis encompasses changes including irregular intimal thickening, intimal and medial fibrosis, focal areas of persistent chronic inflammation, confluent loss of the elastic lamina, and medial neovascularization.[7]

Indications

Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is the gold standard for diagnosis of GCA and aids in decision-making regarding long-term steroid use. The superficial temporal artery is the most common artery sampled. However, alternative arterial sites such as the facial or occipital arteries may be used.[8][9] Color Doppler ultrasonography has been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity when compared to temporal artery biopsy and may be used in some centers as an alternative diagnostic modality. Ultrasonography shows a hypoechoic halo around the lumen of the temporal artery, with unilateral halo having an 82% sensitivity and 91% specificity for GCA and bilateral halos having 100% specificity.[10] However, due to operator dependence and variability in equipment and technique, temporal artery biopsy remains the primary diagnostic procedure to confirm suspected giant cell arteritis in routine clinical practice [11]

Preoperative considerations

While ultrasonography-guided TAB may be performed, it does not increase TAB sensitivity as inflamed portions of the artery may be detected by physical examination.[12]

A majority of clinicians recommend initial unilateral TAB; however, some advocate for initial bilateral biopsy. Others recommend deciding based on clinical suspicion.[13] The rate of discordant biopsies in patients with initial bilateral temporal artery biopsy (1 side negative, 1 side positive) and discordance between localization of symptoms and side of positive biopsy has led to recommendations for initial bilateral temporal artery biopsy.[14]

Due to the segmental nature of GCA, sufficient specimen length is important for accurate diagnosis, and the length of biopsy has been controversial. A 1-2 cm biopsy in vivo may be sufficient; however, the clinician should account for shrinkage of about 10% with fixation alone[15] and plan for a biopsy of >2 cm to increase the accuracy of diagnosis [16]

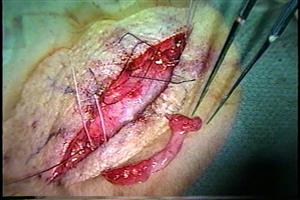

Procedure

Temporal artery biopsies are usually performed under local anesthesia if there are no contraindications. The superficial temporal arteries are palpated bilaterally to assess for patency and signs of arteritis. If the vessel is not easily palpable, hand-held Doppler can be used to localize it. Once the artery is identified, the surgical site is marked. A patent artery is preferred, however a thrombosed artery may show histopathological signs of GCA as well and can be pursued.

Topical lidocaine can be applied prior to lidocaine infiltration. The area is prepared by clipping any hair if present and scrubbed with either povidone iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Local anesthesia with a combination of short and long acting anesthetic (1:1 mixture of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) and 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) is injected into the skin and subcutaneous tissues approximately 1 cm lateral to the site of the artery, on either side. Using a Bard-Parker #15 scalpel and gentle lateral traction, a vertical incision is made overlying the marked temporal artery just through the dermis. The subcutaneous fat in this area is usually minimal and the artery can occasionally be visualized at this point. The incision should provide enough exposure to easily see approximately 3 cm of the vessel; this can be facilitated by the use of a self-retaining retractor or skin hooks. Fine, blunt scissors such as Stevens tenotomy scissors are used to separate the thin layer of subcutaneous fat and expose the superficial temporal fascia. The fascia is elevated with toothed forceps and penetrated with scissor tips. The incision is then expanded to expose the superficial temporal artery. If not readily visible, the area may be palpated or a Doppler probe can be used intraoperatively. The surgeon should minimize manipulation of the artery as much as possible as arterial spasm may occur, which can cause histologic artifact. Three centimeters of the artery should be dissected and isolated. Placement of a vessel loop or silk suture can aid in elevating and stabilizing the artery during dissection.

The artery is ligated proximally and distally or small hemostats are used to clamp proximally and distally and the intervening segment is excised for biopsy. The arterial stumps are ligated with non-absorbable sutures and hemostasis is assisted with pressure, electrocautery, and/or topical agents. The wound is irrigated and the skin is closed. The skin may be closed with surgical staples, or absorbable sutures in multiple layers. Ointment or a surgical dressing may be placed over the incision.[17]

Postoperative Management

The procedure is generally performed in the outpatient setting and patients are instructed on home wound care. If a dressing is placed, it should be maintained for 24 hours after which time the outer self-adhesive film can be removed. Antibiotic ointment such as bacitracin should be applied to the incision daily.

Complications

- Bleeding

- Hematoma

- Infection

- Nerve damage

- Scarring

- Wound dehiscence

Additional Resources

- Video of temporal artery biopsy: https://www.aao.org/basic-skills/temporal-artery-biopsy

- Video of temporal artery biopsy: https://www.aao.org/clinical-video/temporal-artery-biopsy-22

- https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/diagnosing-giant-cell-arteritis

References

- ↑ Rubio-Rivas M, Bajinay SD, Martorell JC & Formiga F (2011): [Repetition stroke as onset of giant cell arteritis]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 46: 231-233.

- ↑ Godoy P, Araujo Sde A, Paulino E Jr & Lana-Peixoto MA (2007). Coronary giant vell arteritis and acute myodardial infarction. Arq Bras Cardiol 88, e84-87.

- ↑ Jonasson F, Cullen JF & Elton RA (1979): Temporal arteritis: a 14 year epidemiological, clinical and prognostic study. Scott Med J 24: 111-117.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ness T, Bley TA, Schmidt WA, Lamprecht P. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Giant Cell Arteritis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2013;110(21):376-386. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0376.

- ↑ Grzybowski A & Stacy R (2015). Temporal artery biopsy in giant cell arteritis. JAMA Ophthal. 133(10): 1220.

- ↑ Stacy RC, Rizzo JF & Cestari DM (2011). Subtleties in the histopathology of giant cell arteritis. Semin Ophthalmol 26: 342-8.

- ↑ Lee YC, Padera RF, Noss EH, et al. Clinical Course and Management of a Consecutive Series of Patients with “Healed Temporal Arteritis.” The Journal of Rheumatology. 2012;39(2):295-302. doi:10.3899/jrheum.110317

- ↑ Kattah JC, Cupps T, Manz HJ, el Khodary A & CaputyA (1991). Occipital artery biopsy: a diagnostic alternative in giant cell arteritis. Neurology 41(6): 949-50.

- ↑ Achkar AA, Lie JT, Gabriel SE & Hunder GG (1995) Giant cell arteritis involving the facial artery. J Rheumatology 22(2): 360-2.

- ↑ Karahaliou M, Vaiopoulos G, Papaspyrou S, Kanakais MA, Revenas K & Sfikakis PP (2006). Colour duplex sonography of temporal arteries before decision for biopsy: a prospective study in 55 patients with suspected giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 8(4): R116.

- ↑ .Arida A, Kyprianou M, Kanakis M, Sfikakis PP. The diagnostic value of ultrasonography-derived edema of the temporal artery wall in giant cell arteritis: a second meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:44.

- ↑ Germanò G, Muratore F, Cimino L, Lo Gullo A, Possemato N, Macchioni P, Cavazza A, Pipitone N, Boiardi L & Salvarani C (2015). Is colour duplex sonography-guided temporal artery biopsy useful in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis? A randomized study. Rheumatology. 54(3); 400-4.

- ↑ Schallhorn J, Haug SJ, Yoon MK, Porco T, Seiff SR & McCulley TJ (2013). A national survey of practice patterns: temporal artery biopsy. Ophthalmology. 120(9): 1930-4.

- ↑ Durling B, Toren A, Patel V, Gilberg S, Weis E & Jordan D (2014). Incidence of discordant temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Can J Ophthalmol. 49(2): 157-61.

- ↑ Gordon LK & Levin LA (1998). Visual loss in giant cell arteritis. JAMA. 280(4): 385-6.

- ↑ Goslin BJ & Chung MH (2011). Temporal artery biopsy as a means of diagnosing giant cell arteritis: is there over-utilization? Am Surg. 77(9):1158-60.

- ↑ Albertini, J. G., Ramsey, M. L. and Marks, V. J. (1999), Temporal Artery Biopsy in a Dermatologic Surgery Practice. Dermatologic Surgery, 25: 501–508.