Silent Brain Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Silent Brain Syndrome refers to progressive bilateral enophthalmos in patients with a history of early ventriculo-peritoneal shunting (VPS) for hydrocephalus. Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, it is thought that the sudden decrease in intracranial pressure (ICP) from VPS in childhood causes a decrease in pressure of the anterior cranial fossa against the orbital roof, leading to bony remodeling and expansion of the bony orbit.[1] Patients initially present with bilateral progressive enophthalmos and symptoms of diplopia, exposure keratopathy, corneal ulcers, epiphora, entropion, lid retraction and/or lagophthalmos.

Epidemiology

Silent Brain syndrome (SBS) is a rare disorder that generally occurs in patients with a history of childhood hydrocephalus treated with VPS. The incidence of SBS is rare and limited to case series and reports.[2][3][4][5] The average age of shunting in patients with SBS is 12 years (range infancy-25 years).[6] The mean age of symptom onset is 20.4 years, and the mean age of presentation to the ophthalmologist is 27.5 years. [2] No racial or gender predilection has been identified but a recent study found a slight male predominance with a male to female ratio of 3:2.

Anatomy

The orbit is a cone-shaped cavity composed of a strong bony rim and relatively weak orbital walls that surround and protect the eye. Fat, muscle, connective tissue, and neuro-vasculature fill the extraconal and intraconal spaces that surround the globes. The frontal bone forms the orbital roof and floor of the anterior cranial fossa and is concave in contour. The floor is composed of sphenoid and the orbital process of both the maxillary and palatine bones, which slopes upward posteriorly and medially. The medial wall is formed by the frontal process of the maxilla, lesser wing of the sphenoid, the ethmoid bone, and the lacrimal bone. The lateral wall is composed of the frontal and zygomatic bones facially and the greater wing of the sphenoid apically. The bones at the apex of the orbit are generally the strongest and thickest. There is thinning of the bones as the walls of the orbit move anteriorly until the bones thicken again to form the rims of the globe.[7] Changes in the pressure gradients within the calvarium can alter the bony anatomy of the developing orbit in a child leading to SBS.

The extraconal space lies within the orbit outside the musculofacial cone and contains the lacrimal gland, orbital fat, muscle, connective and neurovascular tissue.[8] These structures are critical in maintaining the position of the globe and facilitating extraocular movements of the eye. Loss of intraconal or extraconal fat is a well-known mechanism of nontraumatic enophthalmos and can also be seen in patients with SBS.

The anatomy of the upper and lower eyelids is essential in protecting the eyes by maintaining proper closure and lubrication of the eye. Poor apposition of the eyelids to the globe, as is seen in SBS, disrupts the normal function of the eyelids leading to a variety of pathological states.

Pathophysiology

While the pathophysiology for SBS is not completely established, it is hypothesized that the change in pressure gradients across the orbital roof is the initiating factor in the bony remodeling observed in SBS. Increased intracranial pressure in childhood, relieved by VPS, can cause decreased pressure of the anterior cranial fossa against the orbital roof, leading to bony remodeling and progressive expansion of the developing orbit. [9] In healthy patients, ICP may drop below atmospheric pressure while sitting or standing; however, in patients that have a VPS with no valve, ICP can drop to a negative pressure more frequently. When the atmospheric pressure is greater than the ICP, an upward force on the orbital roof is created. Progressive bowing of the thin orbital roof results from the differential pressure gradient. Progressive enlargement of the orbit is observed over time leading to enophthalmos. [10]

Although SBS is most commonly a complication of VPS within the first 2 decades of life, silent brain syndrome has also been described in adult patients with previously normal orbital anatomy. In a recent case report, leptin, a known regulator of bone formation, was markedly elevated in the CSF, suggesting that ICP may drive neuroendocrine changes that affect bone remodeling.[11] Similarly, a 2002 case described bilateral enophthalmos consistent with SBS due to Paget’s disease thought to be a result of increased osteoclast activity causing bony uptake and remodeling.[12]

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms

The clinical presentation is influenced by the degree of enophthalmos and can vary significantly from patient to patient. Patients typically present with complaints of tearing, discharge, foreign body sensation, feelings that their eyes are “sunken in,” diplopia, and worsening vision.

Physical Examination

A comprehensive ophthalmologic examination should be performed including visual acuity, pupils, intraocular pressure, and visual fields. External examination should evaluate for increased head circumference, enophthalmos and lid position. Exophthalmometry should be performed. A thorough slit lamp examination should be performed with focus on the position and appearance of the eyelids and lashes, conjunctival injection, and cornea.

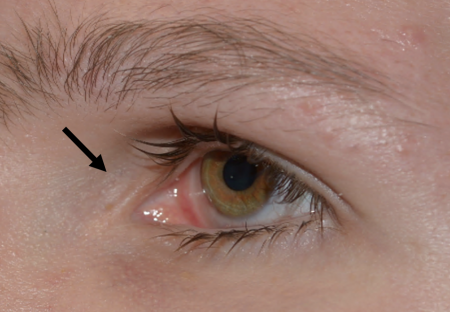

Signs

Bilateral enophthalmos is the most prominent feature in SBS and may be largely asymmetric. Other signs include superficial exposure to keratopathy, epiphora, trichiasis, entropion, lagophthalmos and lid retraction, and decreased peripheral visual fields. [2][12] Corneal perforation has been reported as a complication of SBS. [13]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SBS is based on the combination of clinical presentation, medical history, ophthalmologic and orbital examination, and radiographic imaging. A positive history of VP shunting with supporting physical exam findings should prompt consideration of SBS. Computed tomography scan (CT) of the orbit should be performed to confirm enophthalmos and evaluate for other orbital pathology.

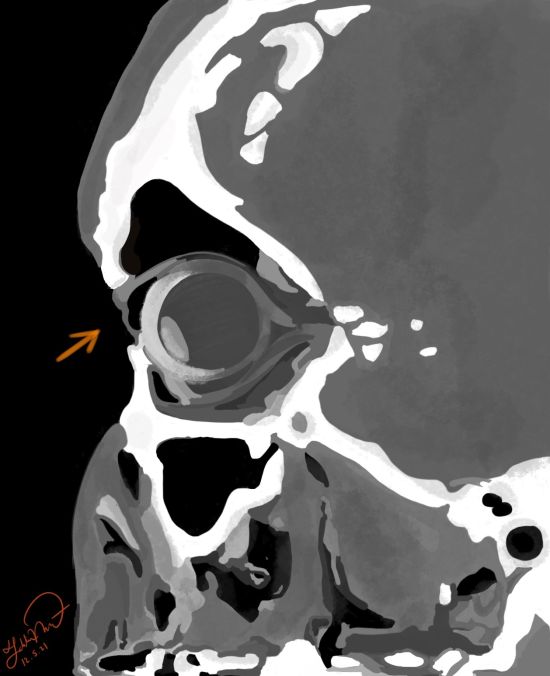

Diagnostic Imaging

CT of the orbit is the imaging modality of choice to demonstrate the bony anatomy; however, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be recommended in children to decrease radiation exposure. In SBS, CT scan can reveal a normal size globe with enophthalmos, air entrapment of the upper eyelid, and bowing of the orbital roof.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis may be broken up into four categories, which include: pseudo-enophthalmos, structural abnormality, orbital soft tissue loss, retraction.

Pseudo-enophthalmos:

- Ipsilateral upper eyelid ptosis

- Contralateral exophthalmos

- Horner’s syndrome

Structural Abnormality:

- Trauma (orbital fractures)

- Iatrogenic orbital decompression

- Silent sinus syndrome - syndrome (chronic sinusitis with most common findings of enophthalmos and hypoglobus)

- Silent brain syndrome

- Orbital Varix- typically shows unilateral intermittent non-pulsatile proptosis with maneuvers that increase venous pressure, without an associated bruit. However, Long-standing lesions can be associated with enophthalmos at rest, possibly due to atrophy

- Osteomyelitis

- Anophthalmic enopththalmos

Orbital soft tissue loss:

- Orbital fat atrophy

- Phthisis Bulbi - Atrophy of the globe due to severe scarring from multiple ocular insult

- Post-Radiation - soft tissue atrophy

- Parry-Romberg Syndrome - hemi-facial atrophy

Retraction:

- Duane retraction syndromes

- Congenital fibrosis of extra-ocular muscles

- Metastasis to ocular muscles

Management

Early identification of intracranial hypotension due to VPS and correction of intracranial pressure may halt disease progression or prevent future SBS in young patients being treated with hydrocephalus. Typically, patients with silent brain syndrome have an extensive past medical history that warrants a multidisciplinary approach with general medicine, ophthalmology, oculoplastic and reconstructive surgery, and neurosurgery.

Management of SBS is based on the extent of enophthalmos and the sequelae associated with it. The main complications from progressive enophthalmos include:

- Corneal complications such as dry eye syndrome, exposure keratopathy, infectious keratitis, increased epiphora and decreased visual acuity from poor lid apposition.

- Visual field deficit such as superior deficit from resultant ptosis or nasal visual field deficit due to obstruction from the nose in a posterior globe position.

- Diminished visual acuity due to an asymmetric, posterior position of the globe causing poor depth perception, image size and magnification between the two eyes.

- Negatively affected appearance, especially in the more vulnerable young adult group that is most affected.

Management of the above complications are approached in a non-surgical and surgical management depending on the extent of enophthalmos progression, associated sequelae, and the impact on patient’s daily function.

Non-surgical management

Non-surgical management primarily consists of treating the corneal surface to prevent exposure keratopathy, infectious keratitis, and improve corneal comfort and visual acuity. Dry eyes can be mitigated through several methods including preservative-free artificial tears and lubricating ointments, available over the counter. Lid scrubs with baby shampoo can improve blepharitis to improve the ocular surface. Warm compress can liquefy meibomian gland contents to improve function and help retain tears on the ocular surface. Additionally, punctal plugs, immunomodulator drops such as Restasis (Cyclosporine) and Xiidra, can also improve corneal lubrication. [2]

Surgical Management

Surgical management is utilized to address asymmetric globe position to enhance appearance aesthetically, increase visual field, improve depth perception and image magnification, and additionally address corneal complications with improved lid apposition. The goal of SBS surgery is to develop symmetry in globe positions. This can be done by moving the globe forward, moving the eyelids backwards, or a combination of both. Orbital augmentation is most commonly used, either with an orbital floor or roof implant. [15]Additionally, lid apposition can be improved solely by orbital augmentation or by tightening the eyelids by repositioning the medial and/or lateral canthal tendons. Once final globe positions are achieved, patient may undergo strabismus surgery to improve extra-ocular movement and alignment for any residual diplopia.

There are four surgical approaches that are utilized in SBS:

- Orbital floor implant: Orbital floor augmentation is the most established technique to improve enophthalmos and achieve eyelid-globe apposition. However, there is a theoretical risk of increasing the forces which causes the roof bowing.[16]

- Orbital roof implant: Bridging of the orbital roof using an implant narrows the space of the superior orbit where bowing has created extra volume to improve globe position.

- Repositioning of the eyelids: Posterior fixation of the medial and lateral canthal tendons using titanium T plates on the medial and lateral canthal tendons to bring back the entire eyelid apparatus has been described.[11] This is typically employed after orbital roof or floor implant.

- Temporary or permanent tarsorrhaphy: This is a relatively simple and highly effective method used to to tighten lids to improve contact of lid to globe. This method is used in patients who have an active corneal process that requires immediate intervention to promote corneal healing, to bridge a patient until more definitive surgery, or in patients who are poor surgical candidates.

Strabismus surgery: This may be considered after orbital augmentation and any associated eyelid surgeries. If patients continue have diplopia and strabismus, recession or resection of the ocular muscles may be performed. Refractive prisms may also be considered prior to surgical intervention or for residual strabismus postoperatively.

Complications of orbital surgery

The most common complications of orbital implantation include implant migration (13%), insufficient orbital volume (10%), exposure/extrusion/infection (8%), mechanical obstruction (1%) and socket edema (1%).[17] Other complications of orbital augmentation surgery include under- or over-correction of orbital volume, scarring and fibrosis, upper eyelid blepharoptosis, ectropion or entropion, diplopia, and infection.[15] Patients with such complications may present with post-operative pain or discomfort as well as foreign body sensation.

Follow-Up

Follow up of SBS patients varies based on the severity of enophthalmos and are individualized to the patient. If a patient has enophthalmos that can be improved with one surgery, follow up may range from 6 months to 1 year after the initial postoperative period as the globe settles into its final position. Ocular lubrication methods employed pre-operatively should be continued.

- ↑ Pargament JM, Peralta RJ, Nerad JA, McCann JD. Orbital volume augmentation for enophthalmos following ventriculoperitoneal shunting: a case study in “silent brain syndrome”. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3SSuppl1):S168–S171. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000643.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Hong E, Allen R. Slient Brain Syndrome. EyeRounds.org - Ophthalmology - The University of Iowa. (n.d.). Retrieved December 4, 2021, from https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/125-silent-brain-syndrome.htm.

- ↑ Bernardini FP, Rose GE, Cruz AA, Priolo E. Gross enophthalmos after cerebrospinal fluid shunting for childhood hydrocephalus: the “silent brain syndrome”. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25(6):434–436. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181b80d2d.

- ↑ Hwang TN, Rofagha S, McDermott MW, Hoyt WF, Horton JC, McCulley TJ. Sunken eyes, sagging brain syndrome: bilateral enophthalmos from chronic intracranial hypotension. Ophthalmology. 2011;118 (11):2286–2295. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.04.031.

- ↑ Pirakitikulr N & David T. Tse (2021): A Natural History of Silent Brain Syndrome over 36 Years: A case report, Orbit, DOI: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1866023

- ↑ Pirakitikulr N & David T. Tse (2021): A Natural History of Silent Brain Syndrome over 36 Years: A case report, Orbit, DOI: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1866023

- ↑ Turvey TA, Golden BA. Orbital anatomy for the surgeon. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;24(4):525-536. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2012.08.003

- ↑ Turvey TA, Golden BA. Orbital anatomy for the surgeon. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2012;24(4):525-536. doi:10.1016/j.coms.2012.08.003

- ↑ McCulley TJ, Jordan Piluek W, Chang J. Intracranial pressure and skull remodeling. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29(1):57-62. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.12.003

- ↑ Yoon MK, Parsa AT, Horton JC. Skull thickening, paranasal sinus expansion, and sella turcica shrinkage from chronic intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;11(6):667–672. doi:10.3171/2013.2.PEDS12560.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pirakitikulr N & David T. Tse (2021): A Natural History of Silent Brain Syndrome over 36 Years: A case report, Orbit, DOI: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1866023

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Chen JJ, Cohen AW, Wagoner MD, Allen RC. The “silent brain syndrome” creating a severe form of the “giant fornix syndrome”. Cornea. 2012;31(9):1065–1067. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823f8e65.

- ↑ Magalhaes OA, Lima MC, Golbert MB, Klein LB, Mörschbächer R. Corneal Perforation associated with "Silent Brain Syndrome". Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2023 Jan-Feb;86(1):68-70. doi: 10.5935/0004-2749.20230004. PMID: 35170650.

- ↑ McCulley TJ. Sphenoid sinus expansion: a radiographic sign of intracranial hypotension and the sunken eyes, sagging brain syndrome (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2013;111:145–154.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dresner SC, Codère F, Corriveau C. Orbital volume augmentation with adjustable prefabricated methylmethacrylate subperiosteal implants. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991 Jan;22(1):53-6. PMID: 2014113.

- ↑ Pargament JM, Peralta RJ, Nerad JA, McCann JD. Orbital volume augmentation for enophthalmos following ventriculoperitoneal shunting: a case study in “silent brain syndrome”. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;33(3SSuppl1):S168–S171. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000643.

- ↑ Chalasani R, Poole-Warren L, Conway RM & Ben-Nissan B (2007): Porous orbital implants in enucleation: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol 52: 145–155.