Normal Tension Glaucoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Summary

Normal tension glaucoma (NTG) is a common form of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) in which there is no measured elevation of the intraocular pressure (IOP). The clinical characteristics of NTG have many similarities to those in POAG, with a few notable distinctions. Like POAG, NTG is a chronic, progressive optic neuropathy that results in a characteristic optic nerve head cupping, retinal nerve fiber layer thinning and functional visual field loss. Careful and complete review of history, physical exam findings, and diagnostic testing are key to distinguishing NTG from other common forms of glaucomatous and non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy. The role of IOP in the pathogenesis of NTG is an area of controversy prompting research into a variety of IOP independent factors such as vascular dysregulation, hypotension, and lamina cribrosa abnormalities that may have some role to play in the development of this disease. Therefore, other proposed interventions in NTG have aimed at modification of blood pressure and optic nerve perfusion in addition to neuroprotection as a means of slowing disease progression independent of an IOP lowering mechanism. Despite the lack of an observed IOP elevation, the current medical and surgical treatment of NTG continues to be aimed at lowering IOP as in other forms of POAG.

Disease Entity

Normal pressure glaucoma, an open angle glaucoma.

Intraocular Pressure in the Population

Glaucomatous optic neuropathy is a clinical phenomenon without a single clear pathophysiologic mechanism. The term glaucoma is defined clinically as visual function loss in the setting of the characteristic ‘cupping’ of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. In the setting of an open anterior chamber angle (open angle glaucoma), these pathologic changes are observed over a range of normal, supernormal, and subnormal intraocular pressures.

Early recognition of glaucomatous optic neuropathy in the setting of physiologic intraocular pressure was described by Von Graefe in the mid 19th century[1]. Given the unclear etiology of the condition, many clinical definitions have been put forth guided by proposed mechanisms and efforts to describe the disease[2]. In 1980, Levene published an exhaustive critical review of the literature and personal cases leading to the widely used descriptive definition of normal tension glaucoma used today[3][4].

Within the spectrum of primary open angle glaucoma, patients with physiologic intraocular pressures have been classified as having normal tension glaucoma (NTG) or, less accurately, low tension glaucoma (LTG).

As reliable tonometric means became available in the mid 20th century, large population based studies of intraocular pressure were performed[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]. Although the general distribution is skewed towards higher IOPs[15], these studies have established the means to calculate the estimated range of physiologic IOP. Assuming a normal “Gaussian” distribution of intraocular pressure, a consensus has emerged defining the upper limit of normal IOP to be ~21 mmHg (2 standard deviations above the mean). Establishment of these norms has revealed that a significant portion of POAG patients have normal pressures as demonstrated in the Baltimore eye survey where 50% of patients identified with POAG had untreated IOP of <22 mmHg.[16]

Etiology

The development of glaucomatous optic neuropathy in general likely results from several factors that are mechanical, vascular or neurodegenerative in origin. Despite the lack of a single identifiable causal process, increased intraocular pressure has been identified as the most important modifiable risk factor in open angle glaucoma. The pathologic changes that occur in normal tension glaucoma are even less understood, but likely share contributing factors with all POAG. A host of causative factors independent to IOP have been suggested including systemic and local vascular dysregulation, hematologic abnormalities, impaired CSF circulation resulting in stagnation and decreased optic nerve protection, and structural anomalies including structural weakness of the lamina cribrosa. Drance and colleagues described two forms of NTG: 1) a non-progressive form typically associated with a transient episode of vascular compromise, and 2) a progressive form thought to result from a chronic vascular insufficiency at the optic nerve[17].

It has been theorized that the disease process in NTG results from an enhanced sensitivity to what would otherwise be physiologic IOP, resulting in glaucomatous damage of the optic nerve. This enhanced sensitivity may be due to impaired optic nerve blood flow, a higher translaminar pressure gradient (IOP-ICP) due to lower ICP, or a structurally abnormal lamina cribrosa, which cannot withstand a normal range of IOP. This theory of enhanced sensitivity is useful, at least conceptually, to rationalize the impact of IOP in a disease process that may indeed have an IOP independent underlying etiology. The evidence for a role of IOP contributing to the disease comes from the Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study[18][19], which showed a slowing of disease progression in patients achieving a 30% or more reduction of already normal IOP. While some try to delineate NTG and POAG as two completely unique disease processes, it has also been suggested that the diseases exist on a continuum with IOP playing a larger role in POAG, and vascular or mechanical factors at the etiologic root in NTG.

Risk Factors

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of NTG presents an intriguing challenge for researchers and clinicians. While the exact prevalence of NTG can vary by geographic region, it is estimated to comprise a significant proportion of all glaucoma cases, with some studies suggesting it may account for up to 30-40% of all glaucoma patients.[20] The proportion of NTG amongst POAG was reported as high as 92.3% in Japan (the Tajimi Study), 84.6% in Singapore (the Singapore Malay Eye Study), 83.58% in northern China (the Handan Eye Study), 82% in south India (the Chennai Glaucoma Study), 79.6% in southern China (the Liwan Eye Study), 77% in South Korea (the Namii Study), yet only 31.7% in the United states of America (the Beaver Dam Eye Study) demonstrating that there is a predilection for those of Asian descent.[21] Current research tackles the disparity demonstrated by the aforementioned data, suggesting that other factors/predispositions within specific ethnic groups may be playing a significant role in the pathogenesis of NTG.

NTG is typically not considered to be a heritable disease, as approximately 2% of NTG cases are caused primarily by a mutation of a single gene and found to be transmitted by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Nevertheless, individuals who carry one of the many autosomal dominant gene mutations may present with symptoms of NTG as early as 23 years old.[22] Genetic and pedigree studies continue to further elucidate numerous new genes associated with the development of NTG, but further studies that demonstrate a higher incidence of disease are necessary before a clinical indication for genetic screening/counseling can be recommended.

A recent cross-sectional study aimed to further describe a potential link between the incidence of NTG in patients with dementia. The study demonstrated an association between NTG status and poor cognition (measured with the Telephone Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, T-MoCA) thereby concluding that there exists a disease association and shared features between NTG and dementia when compared to those with high tension glaucoma (HTG).[23] Conversely, a recent study demonstrated that persons with NTG had increased risk for developing vascular dementia (VaD), with particular increased risk when diagnosed with glaucoma at ages >70.[24]

Optic nerve and anatomical features

Though the quantity of axons that compose optic nerves in humans remains a predictable constant between individuals, variability in surface area of optic discs is observed. It is unclear if certain optic nerve head parameters place an eye at increased risk of NTG. Optic nerves with a larger surface area and with thinner inferior/inferotemporal rims have been reported to be at an increased risk for developing NTG.[25][26] Other studies evaluating the optic nerve head by scanning laser ophthalmoscopy found no morphologic differences between high-tension and normal tension glaucoma patients[27].

Frequently an area of peripapillary atrophy in a crescent or halo configuration is observed in patients with NTG. While this pattern of atrophy can be a finding in eyes without NTG, in glaucomatous eyes, peripapillary atrophy often occurs adjacent to areas of greatest disc thinning and corresponding visual field loss[28]. While thinning of the optic nerve rim is observed in all POAG, focal thinning or ‘notching’ is more commonly observed in NTG.[29]

Classically, the presence of small flame shaped optic disc hemorrhages, also known as Drance hemorrhages, has been associated with NTG though this finding can be observed in any form of POAG. Anderson et al reported the presence of optic disc hemorrhages at the time of diagnosis of NTG as an unfavorable prognostic marker for likely visual field progression.[30]

Intraocular Pressure

Although always residing within the normal range for IOP, patients with NTG have been suggested to have higher-normal IOP levels[31]. By contrast, prospective evaluation of patients in the Low-Pressure Glaucoma Treatment Study found no relation between IOP asymmetry and visual field asymmetry[32]. Wide diurnal fluctuations in IOP and nocturnal IOP spikes have also been correlated with NTG[31].

Systemic vascular disease

Patients with systemic conditions that result in ischemic vascular disease such as diabetes and patients with a history of stroke have been shown to be at increased risk for bilateral NTG compared to unilateral NTG . Patients with NTG may have increased diastolic blood pressure and display larger dips in blood pressure overnight compared to normal . Similarly, it has been suggested that Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) may lead to transient episodes of nocturnal hypoxemia and compromised optic nerve head perfusion. In fact, a higher prevalence of OSA among NTG patients has been noted in several studies[33][34][35]. Moreover, one study demonstrated a correlation between moderate/severe OSA and higher progression of RNFL loss[36].

Certain vasospastic conditions such as Raynaud phenomenon are thought to be associated with NTG, with the most reported associated condition being migraine.[37] Recently, a disease entity termed primary vascular dysregulation (PVD) has been described pointing to retinal and optic nerve vasculature dysregulation as a potential risk factor for NTG[38].As above, a recent study demonstrated a significantly increased risk of developing vascular dementia (VaD) in individuals diagnosed with NTG, further supporting a vascular deregulatory element in the pathogenesis of NTG.[39]

A recent cross-sectional study investigated the prevalence of NTG in patients with primary aldosteronism (PA). Of the 212 patients with PA included in the study, the prevalence of NTG in PA patients was 11.8%, significantly higher than in hypertensive patients without PA (5.2%). The study found a fourfold increase in the odds of developing NTG in PA patients compared to those without PA (odds ratio = 4.019, P = .022). These findings suggest that aldosterone dysregulation may contribute to the development of NTG, independent of blood pressure, and highlight the need for further research on the potential neuroprotective effects of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in NTG patients with PA.[40]

Another recent manuscript explored potential clinical links between NTG and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), focusing on shared neurodegenerative mechanisms. Both NTG and AD are progressive conditions, sharing risk factors such as age, female sex, and vascular dysfunction. Neuroimaging studies reveal that NTG may have cerebral manifestations similar to AD, further suggesting common mechanisms. Moreover, biomarkers like amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau proteins, traditionally linked with AD, have been implicated in NTG, indicating overlapping pathological processes. While connections between the two diseases remain debated, understanding NTG as part of a broader neurodegenerative spectrum may enhance both diagnostics and treatments for NTG, potentially offering insights into AD pathogenesis. Further research is needed to elucidate the exact relationship between NTG and AD.[41]

General Pathology

Specific histological studies of eyes with NTG are sparse but in general mimic those changes seen in POAG. Histopathologic changes of the optic nerve head include disarrangement and posterior bowing of the lamina cribrosa along with loss of nerve fibers[42]. Non-invasive imaging by OCT and scanning laser modalities have characterized thinning of the peripapillary choroid[43] as well as thinning of the ganglion cell layers in NTG patients compared to other POAG and normal patients[44]. In Asian patients this thinning has been correlated with vascular narrowing in asymmetric NTG when compared to normal fellow eyes and POAG patients with elevated pressures[45][46][47].

Pathophysiology

As previously discussed, the mechanism for the development of glaucomatous optic neuropathy is unknown and remains an area of active research and debate. Even less understood is how these pathologic changes occur in the setting of normal IOP levels. Current research is in part directed towards the physiologic forces that affect perfusion of the optic nerve vasculature as well as cellular oxidative changes that occur with changes in perfusion. The relationship between systemic hypertension and hypotension, ocular vascular perfusion pressure, and local regulation of ocular blood flow by vascular tone mediators such as endothelin seem to play a role in maintenance of a constant perfusion of optic nerve tissues. One theory suggests that perturbation of this perfusion by variability in these parameters leads to oxidative stress by the generation of reactive oxygen species resulting in cellular damage, apoptosis of ganglion cells, and tissue remodeling characteristic of glaucomatous optic neuropathy[48]. In addition, mechanical factors are being investigated as to their role in the pathogenesis of optic neuropathy. Focal and/or diffuse compromise in the structural integrity of the lamina cribrosa has also been suggested in the pathogenesis of the disease[49]. Another recent theory hypothesizes that failure of the glymphatic system in the optic nerve may be involved in NTG, resulting in reduced removal of metabolic waste products in the optic nerve, ultimately resulting in glaucomatous damage.[50] Additionally, many theorize that CSF dysregulation may play an integral role in the development of NTG, as low retrobulbar cerebrospinal fluid pressure (CSFP) may be the cause of elevated translaminar cribrosa pressure difference (TLCPD), rather than elevated IOP.[21] All of these mechanisms need further research to better define the pathophysiology of the disease process.

Genetics

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in NTG, with 21% of patients reporting a family history of glaucoma. Four major genes have been implicated in NTG: optineurin (OPTN), TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1), methyltransferase-like 23 (METTL23), and myocilin (MYOC). OPTN mutations, particularly the E50K variant, have been strongly associated with NTG, causing early-onset disease, large cup-to-disc ratios, and retinal ganglion cell death. TBK1 copy number variations (CNVs) have also been linked to NTG, with duplications and triplications contributing to RGC loss. METTL23 mutations were recently identified in familial NTG cases, with evidence suggesting that these mutations impact histone arginine methylation, potentially leading to RGC degeneration. MYOC, commonly associated with POAG, has been implicated in some NTG cases, though its role remains less clear. Further genetic research is certainly needed to better understand its role in this disease.[51]

Primary Prevention

Screening for and treatment of risk factors associated with normal tension glaucoma, such as nocturnal hypotension, currently does not have a defined role in primary prevention of the condition, particularly in the United States. The hope for improved future understanding of the mechanism of disease development may lead to preventive interventions in patients at risk but at this time is not a standard clinical practice.

A recent study that took place in China aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a health examination center-based glaucoma screening program in identifying early-stage glaucoma cases. They compared 76 patients identified through this screening program with 272 consecutive outpatient cases from the same hospital. The findings indicate that patients detected through the screening program had significantly lower intraocular pressure (IOP) and were more likely to have normal tension glaucoma. These screening-detected patients also had less visual impairment and better visual field test results compared to clinic patients. The study suggests that health examination center-based glaucoma screening is effective in detecting early-stage glaucoma, especially those with NTG, and can complement opportunistic glaucoma detection.[52] This is important in a country like China, where glaucoma is a significant public health concern. Further studies must take place to further characterize the role of primary prevention/screening for NTG before it potentially develops into standard practice, particularly in the US where the incidence of NTG is significantly less than in China. Nevertheless, the aforementioned study demonstrates a potential role for glaucoma screening in patients that are particularly high risk.

Diagnosis

As with the broader spectrum of primary open angle glaucoma, the diagnosis is made by perimetric identification of characteristic visual field defects as well as progressive excavation or ‘cupping’ of the optic nerve from focal or diffuse thinning of the optic nerve rim. In addition, the measured IOP must always be less than or equal to 21 mm Hg.

History

A thorough history is important in the evaluation of the glaucoma suspect patient to uncover evidence of the condition, but also to detect other neurologic conditions that may be masquerading as NTG. A review of accompanied neurologic symptoms such as headache, weakness, dizziness, diplopia, or loss of consciousness should be performed. Particular attention should be given to review of prior episodes of ocular trauma or inflammation as to elucidate possible prior intraocular pressure elevation or other causes of optic neuropathy. Past use of medications, such as systemic, topical, inhaled, or nasal steroids, that can elevate intraocular pressure should be investigated. Inquiries should be made into conditions that may be causal or co-exist with compromised ocular perfusion such as sleep apnea, syncope, Raynauds phenomenon, anemia, hypotension, or prior events of significant vascular compromise requiring blood transfusions. Queries should be made regarding the presence of systemic hypertension or hypotension and any current treatments for these.

Physical Examination

Complete ophthalmologic examination is essential as a means of excluding other forms of glaucoma or confounding visually significant conditions (such as other forms of optic neuropathy) that may shape interpretation of subsequent imaging or perimetry testing. Features of the clinical exam should include:

- Visual acuity

- Color vision testing (to help differentiate from non-glaucomatous optic neuropathies)

- Intraocular pressure measurement

- Diurnal or supine intraocular pressure measurement (if possible)

- Pachymetry

- Afferent pupillary response testing

- Gonioscopy

- Complete slit lamp examination of the anterior segment

- Dilated fundus examination with optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) assessment

Signs

Characteristic focal or diffuse thinning of the optic nerve head rim, as discussed above, is the physical examination hallmark of all glaucomatous disease. Characteristically, the following features may be more frequently seen in NTG compared to POAG:

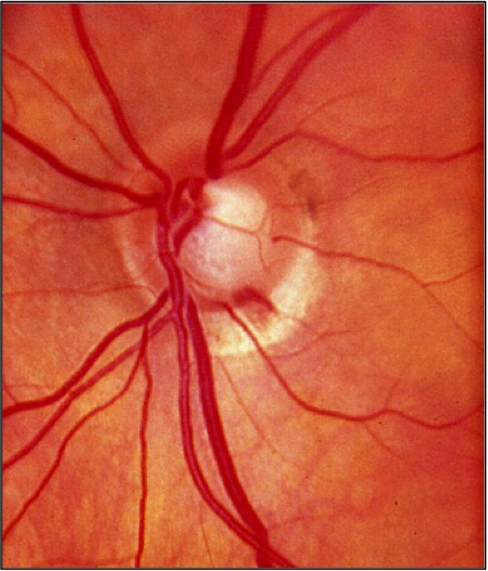

- Flame shaped hemorrhages of the optic nerve rim (Drance hemorrhage) (see figure 1)

- Deep, focal notching of the rim

- Peripapillary atrophy

Figure 1: Optic disc photograph of a left eye demonstrating a hemorrhage occurring at the inferotemporal rim.

Symptoms

As with all forms of open angle glaucoma, the condition is typically asymptomatic until very advanced. Patients may occasionally present with a subjective scotoma near fixation as these defects can occur early in the disease process of NTG.

Clinical diagnosis

Normal tension glaucoma is a diagnosis made based on similar criteria to primary open angle glaucoma but with important clinical distinction.

These features include:

- Progressive excavation or ‘cupping’ of the optic nerve head from retinal nerve fiber layer loss resulting in corresponding visual field deficits.

- Gonioscopic confirmation of open anterior chamber angle and absence of findings consistent with pigment dispersion or pseudoexfoliation syndrome.

- Pre-treatment IOP must always be <22 mm Hg. (diurnal measurement of IOP to ensure there is not a circadian elevation in pressure that is missed by single period clinical measurement)

The diagnosis of NTG is only reached once other forms of optic neuropathy have been ruled out (e.g. ischemic, traumatic, toxic inflammatory, infectious, congenital, and compressive).

Careful history taking should be undertaken to elucidate any prior events that can mimic NTG such as:

- Traumatic injuries

- Inflammation

- Severe blood-loss or hypotensive events

- Medications that may precipitate a transient pathologic elevation in IOP

After reasonable exclusion of all other etiologies, the demonstration of visual field loss on static, or less often kinetic, perimetry in conjunction with characteristic optic nerve central cupping with no elevation in IOP above 21 mm Hg cement the diagnosis.

Other classically associated examination findings with NTG that can be helpful clues in raising suspicion for pursuing a diagnosis include optic nerve or “Drance” hemorrhages and peripapillary atrophy. While these findings are not specific, patients with NTG have a higher propensity for optic nerve hemorrhages compared to patients with POAG. Focal defects in the retinal nerve fiber layer may be more commonly observed as well.

Diagnostic procedures

Visual field testing

Automated static perimetry is the most common modality used to detect and monitor for progression of the field loss associated with normal tension glaucoma. Visual field defects may include those common to POAG including nasal step and arcuate scotoma. However, defects noted in NTG tend to be more focal and occur closer to fixation early in the disease (Figure 2a,b). Dense paracentral scotomas may characteristically be noted at initial diagnosis. For a full discussion of visual field testing see the main article “Standard Automated Perimetry.”

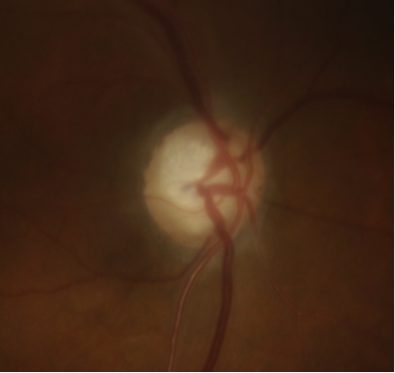

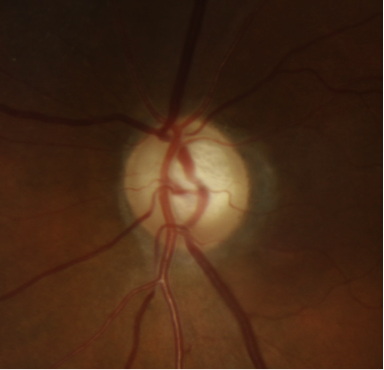

Figure 2: Standard automated perimetry of a) left and b) right eye in a patient with normal tension glaucoma. Note the dense inferior arcuate scotomas occurring near fixation with minimal involvement of periphery. The corresponding optic nerve head changes are seen in Figure 3.

Optic disc imaging

Due to the irreversible loss of vision due to glaucomatous damage, early detection and treatment is paramount. Visual field testing is useful in early detection but may miss early, pre-perimetric disease, as substantial retinal nerve fiber layer may be lost before functional field defects are noted. Therefore, optic disc imaging is an important and objective structural assessment of the optic nerve health. For several decades, the gold standard for detecting disease and monitoring changes in the optic nerve head has been stereo disc photography (Figure 3 a,b). In recent years, scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and optical coherence tomography (OCT) is gaining popularity as another means of detecting pathologic thinning of neural tissue and monitoring progression. (See main article on eyewiki.aao.org/Optic_Nerve_and_Retinal_Nerve_Fiber_Imaging ) Moreover, with the introduction of Artificial Intelligence (AI), OCT interpretation continues to become more prevalent when classifying an eye as either a glaucoma suspect or early NTG. This was demonstrated in a recent study where a deep-learning algorithm was developed to discriminate between the aforementioned diagnoses by using the parameter of Bruch’s membrane opening — minimum rim width, peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness and color classification of RNFL — achieving an area under the curve of 0.966. Ultimately, these advances continue to improve the diagnostic specificity associated with either NTG or POAG.[53]

A recent meta-analysis investigated differences in peripapillary choroidal thickness (PPCT) between POAG, NTG, and healthy eyes. A systematic review of 18 studies, including 935 healthy control eyes, 446 NTG eyes, and 934 POAG eyes, was performed. OCT revealed significant reductions in PPCT in both POAG and NTG eyes compared with healthy eyes. POAG eyes demonstrated a mean reduction in PPCT of −16.32 µm (95% CI −27.55 to −5.09) compared to healthy controls, while NTG eyes showed a larger reduction of −34.96 µm (95% CI −49.97 to −19.95) compared to controls. Additionally, NTG eyes exhibited significantly thinner PPCT compared with POAG eyes, with a mean difference of −26.64 µm (95% CI −49.00 to −4.28). These findings suggest that glaucomatous eyes, especially NTG eyes, have significantly reduced PPCT, highlighting the potential role of PPCT as a diagnostic and monitoring tool in glaucoma management.[54]

Figure 3: Optic disc photographs of a) right and b) left eye in a patient with normal tension glaucoma. Note the focal superotemporal thinning and associated dropout of the retinal nerve fiber layer. The corresponding visual field defects are seen in Figure 2.

Pachymetry

Assessment of central corneal thickness (CCT) through pachymetry is essential in the work up of normal tension glaucoma. The measured IOP by applanation may be artifactually low in eyes with low CCT. Many patients with a diagnosis of NTG will demonstrate a low CCT. In some cases, correction of this under measurement (based on published correction factors[55]) may reveal an actual IOP more consistent with POAG [56].

Neurological Evaluation/Work-Up

At times, the diagnosis of NTG may simulate other neurological conditions such as those listed in the differential diagnosis section below. Most concerning to the clinician is an intracranial tumor masquerading as NTG. While these diagnoses are rare, clinicians should maintain a low threshold for neuroimaging with CT or MRI and a full neurological evaluation whenever the following exist:

- Marked asymmetry or unilateral optic nerve involvement

- Unexplained visual acuity loss

- Color vision deficits in the absence of visual field deficits

- Visual field defects not corresponding or out of proportion to optic nerve damage

- Vertically aligned visual field defects

- Atypical neurologic symptoms for glaucoma

- Optic nerve pallor in excess of cupping

- Age less than 50 years

Differential diagnosis

Glaucomatous etiology

- Primary open angle glaucoma with diurnal fluctuation between normal and elevated IOP

- Intermittent acute angle closure glaucoma

- Tonometric underestimation of actual IOP (e.g. thin central corneas)

- Resolved corticosteroid-induced, uveitic, or traumatic glaucoma

- Uveitic glaucoma/glaucomatocyclitic crisis (Posner-Schlossman)

- ‘Burned out’ pigmentary glaucoma

- Myopia with peripapillary atrophy

- Optic nerve coloboma or pits

- Congenital disc anomalies/cupping

Compressive, metabolic, toxic, inflammatory or infectious optic neuropathy

- Pituitary Adenoma

- Meningioma

- Empty sella syndrome

- Leber’s optic atrophy

- Methanol optic neuropathy

- Optic neuritis

- Syphilis

Vascular injuries

- Giant cell arteritis

- Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Carotid/ophthalmic artery occlusion[57]

Management

General treatment

In general, management of normal tension glaucoma mirrors the medical and surgical management of the other forms of glaucoma and hinges on reduction of IOP from baseline. Identification of patients with clinical evidence of progression is important in the decision to initiate treatment for NTG. The natural history of NTG does not always include progression without treatment. As initially described by Drance, a significant portion of patients with normal tension glaucoma may not demonstrate clinical progression regardless of treatment[17].These patients typically had a history of systemic vascular compromise resulting in a one-time insult to the optic nerve. Nonetheless, for the majority of patients with NTG, reduction of IOP remains the focus of treatment.

The Collaborative Normal Tension Glaucoma Study (CNTGS) demonstrated the benefit of IOP reduction for the treatment of patients with NTG[18][19]. The study concluded that a 30 percent reduction in baseline IOP resulted in a reduced risk of disease progression. Criteria for initiation of treatment of the NTG patients in this study were defined as: documented visual field or optic nerve progression, visual field loss threatening fixation, or presence of disc hemorrhage. The treatment group had a 12% risk of progression at 5 years compared to 35% progressing in the non-treatment group[19]. The CNTGS trial was therefore instrumental in demonstrating the role of IOP in the pathogenesis of NTG and the benefit of treatment to lower it. The study also presents a reasonable goal for treatment in 30% IOP reduction from patient’s baseline. Treatment IOP goals may then be modified over the course of treatment to a level that sufficiently prevents or slows progression of disease.

Outside of IOP lowering therapy, other aspects should be considered in the management of NTG patients. This may include cardiovascular problems such as systemic hypotension, nocturnal hypotension, anemia, and cardiac arrhythmias that can compromise optic nerve head perfusion. Consultation with primary care physicians can be helpful in addressing these concerns, but limited evidence is available to confirm a treatment benefit for NTG.

Medical therapy

Topical IOP lowering medications including prostaglandin analogues, alpha-2 agonists, beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and more recently Rho-kinase inhibitors are the mainstays of medical therapy. Medications should be chosen on an individual basis to provide treatment that achieves a sufficient IOP reduction with minimal side effects and ease of administration. Medication choice should also be cost-effective for the patient based on their resources. For a full discussion of medical management please see the POAG main article.

Particularly with NTG, the effect of medications on systemic blood pressure, heart rate, and optic nerve perfusion should be considered. Furthermore, medications that have neuroprotective or IOP independent effects would be extremely beneficial and remain an ongoing search. The Low-Pressure Glaucoma Study (LoGTS) demonstrated the importance of IOP independent factors when choosing medical therapy for NTG[32]. In this prospective trial, patients with low-tension glaucoma were randomized to treatment with either brimonidine tartrate 0.2% or timolol maleate 0.5%. While IOP reduction was similar between the two treatment groups, patients treated with brimonidine were less likely to have visual field progression compared to patients treated with timolol. It is unclear whether this difference is due to an additional neuroprotective effect of brimonidine or a detrimental vascular effect from timolol. Moreover, Rho-kinase inhibitors are thought to be neuroprotective and increase vascular flow at the ONH via the nitric oxide pathway[58][59]. The newer class of Rho-kinase inhibitor (ROCK) showed efficacy in both IOP reduction in NTG and as add-on treatment in NTG patients with inadequate baseline IOP. This class of medication blocks the contraction of trabecular meshwork cells and increases the outflow of aqueous humor, thereby reducing IOP.[60][61]

In patients with evidence of vasospasm, calcium channel blockers have been proposed to stabilize vascular tone, particularly in patients with concurrent hypertension, though the benefit has not been evaluated in large clinical trials.

Medical follow up

Once treatment is initiated, patients should be followed up 6-8 weeks later to ensure good adherence, minimal side effects, and adequate IOP lowering efficacy. Different medication classes, laser treatment or surgical therapy may be trialed until an appropriate treatment is found. Once treatment goals have been met, periodic measurement of IOP during medical therapy is recommended every 3-4 months to ensure maintenance of goal IOP and absence of progression. New technology has allowed for patients to partake in home tonometry. Patients can frequently report their findings to their supervising ophthalmologists allowing for a more complete representation of IOP mean, peak and range (numerous measurements can be taken throughout the day) and closer follow-up. In addition to IOP, patients should be monitored for signs of progression by periodic assessment of the optic nerve head (disc photos, HRT, OCT, etc.) and visual field testing every 6-12 months, with more frequent intervals in advanced or actively progressing disease. If progression is detected despite goal IOP, treatment goals should be lowered with advance of therapy to achieve them. (also see: Primary_Open-Angle_Glaucoma)

Surgery

Laser and surgical treatment options for NTG mirror those for POAG. These include laser trabeculoplasty, minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS), trabeculectomy, and glaucoma drainage devices.

Selective Laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) may be a useful moderately invasive treatment with or without medical therapy. Indeed, there is some literature that supports an IOP lowering, and decreased IOP variability, effect of SLT in NTG patients. [62] For patients with IOP targets that are not achievable with medical/laser therapy, filtration surgery with or without a drainage device has traditionally been the mainstay of surgically lowering IOP. However, recent trends and practice patterns according to the AAO Intelligent Research Insight Registry (IRIS) reveal a significant increase in the use of MIGS procedures from 2013-2018, and NTG is no exception[63].

Minimally invasive glaucoma procedures such as goniotomy with Kahook Dual Blade (KDB), the iStent trabecular bypass device, and the XEN gel stent have demonstrated an important although limited role in the surgical management of NTG. In theory, angle-based MIGS procedures can only lower IOP to a level equal to or above episcleral venous pressure of approximately 8-11 mm Hg. Goal IOP for NTG patients may be below this level making it difficult to achieve treatment goals by surgical means alone. However, maintaining a goal IOP with fewer medications is a reasonable indication for MIGS in NTG. This rationale also applies to laser trabeculoplasty, which augments aqueous outflow to the downstream episcleral venous system as well. According to AAO IRIS data regarding initial surgery for NTG, iStent has been the most common performed surgery and MIGS procedures in general are performed at a higher rate than filtration surgeries for NTG[64].

In the CNTGS, the IOP reduction of 30% was only achieved in 57% of patients by topical medication and/or laser trabeculoplasty, while the remaining 43% required filtering surgery. While IOP lowering with filtration surgery has been shown to be effective in decreasing visual field progression a continued, slowed progression has been reported in postoperative patients followed for up to 6 years .

A lower starting IOP with NTG patients and a 30% reduction target may result in a narrower margin between therapeutic IOP reduction and hypotony in these patients. Indeed, increase risk of filtering surgery complications has been reported in this subset of POAG patients .

Selection of anti-metabolite drugs and means of application in filtering surgery is an important consideration and should be guided by specific treatment goals and surgeon specific experience with these agents. Mitomycin C (MMC) has been associated with achievement of lower IOPs post operatively compared to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in some studies, though literature also suggests equivalence of efficacy of these two agents in primary trabeculectomy for POAG. MMC use in NTG glaucoma has an associated increased risk of over-filtration complications that may play a role in the risk of visual field progression. Therefore, meticulous use of MMC (e.g. 0.2-0.4 mg/ml for 1-3 minutes), careful flap suturing, and judicious use of viscoelastic with frequent postoperative follow up have been proposed as methods to mitigate the risks of hypotony early in the post operative phase while achieving target IOP. Early suture lysis may be required to achieve low target IOPs but should be weighed against the risk of resultant over-filtration. Given the context of a higher risk of hypotony following filtering surgery in patients with NTG, the XEN gel stent has recently been deployed to achieve a lower IOP goal while maintaining a lower rate of hypotony. One recent study demonstrated a mean IOP decrease of 5.6 +/- 2.7 mmHg in NTG patients, which represented an IOP reduction of 29%[65]. Also, the use of the EX-PRESS glaucoma mini shunt has been employed as a means of preventing complications, while still achieving similar IOP goals compared to standard trabeculectomy. In our experience, the smaller, consistent outflow opening of the EX-PRESS shunt allows for earlier suture lysis to achieve low IOP targets with less risk of hypotony. The utility of this device remains an area of debate considering the additional cost of the device and mixed outcomes in the literature.

Cyclodestructive procedures provide the only surgical means of suppressing aqueous production to lower IOP. Due to their potentially vision threatening side effects, these procedures are typically reserved for eyes refractory to treatment or with poor visual potential. Ablation of the ciliary processes may be accomplished by transscleral cyclophotocoagulation (CPC) or by endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation (ECP). ECP offers the unique advantage of direct visualization of the target tissue allowing a more targeted approach to achieve less inflammation and side effects.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of angle-based MIGS in patients with normal tension glaucoma (NTG). The study analyzed outcomes from 15 studies, totaling 367 NTG eyes, with procedures including the iStent, iStent inject, Hydrus Microstent, Kahook Dual Blade, and Trabectome. The review found significant reductions in IOP and glaucoma medication usage postoperatively. Specifically, combined phacoemulsification and angle-based MIGS showed a mean IOP reduction of 2.44 mmHg at 6 months, 2.28 mmHg at 12 months, and sustained reductions up to 36 months. Glaucoma medication usage was also significantly reduced by 1.21 medications at 6 months and 1.18 at 12 months postoperatively. These findings suggest that angle-based MIGS, particularly in combination with cataract surgery, can be effective in reducing IOP and medication burden in NTG patients while maintaining a favorable safety profile.[66]

(For full discussion of surgical management see: Primary_Open-Angle_Glaucoma).

Prognosis

Like any form of glaucoma, NTG may progress to irreversible blindness. The prognosis for visual preservation is good in patients who undergo adequate treatment through IOP reduction. In the CNTGS trial, 65% of patients in the control group with NTG did not progress even without treatment[19]. However, an IOP reduction of 30% with treatment further lowered the likelihood of progression to only 12%. As mentioned previously, patients with NTG that previously suffered an acute vascular compromise have also been shown to not progress over time as well. Given this relatively high rate of non-progression, some clinicians have suggested a conservative “wait and see” approach to initiating treatment. This recommendation should be cautioned, as it is often difficult to determine which patients will progress, and other studies have shown variable rates of progression in this disease. Risk factors for progression of visual field defects in NTG include migraine, disc hemorrhage, and female gender. Asians have been shown to have a slower rate of progression[67].

References

- ↑ Graefe, A.V., Uber die iridectomie bei glaucom und uber den glaucomatasen prozess. . Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 1857. 1857(3): p. 456–465.

- ↑ Lee, B.L., R. Bathija, and R.N. Weinreb, The definition of normal-tension glaucoma. J Glaucoma, 1998. 7(6): p. 366-71.

- ↑ Levene, R.Z., Low tension glaucoma. Part II. Clinical characteristics and pathogenesis. Ann Ophthalmol, 1980. 12(12): p. 1383.

- ↑ Levene, R.Z., Low tension glaucoma: a critical review and new material. Surv Ophthalmol, 1980. 24(6): p. 621-64.

- ↑ Armaly, M.F., Age and sex correction of applanation pressure. Arch Ophthalmol, 1967. 78(4): p. 480-4.

- ↑ Colton, T. and F. Ederer, The distribution of intraocular pressures in the general population. Surv Ophthalmol, 1980. 25(3): p. 123-9.

- ↑ David, R., et al., Epidemiology of intraocular pressure in a population screened for glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol, 1987. 71(10): p. 766-71.

- ↑ Klein, B.E., R. Klein, and K.L. Linton, Intraocular pressure in an American community. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1992. 33(7): p. 2224-8.

- ↑ Loewen, U., B. Handrup, and A. Redeker, [Results of a glaucoma mass screening program (author's transl)]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1976. 169(6): p. 754-66.

- ↑ Perkins, E.S., Glaucoma Screening from a Public Health Clinic. Br Med J, 1965. 1(5432): p. 417-9.

- ↑ Ruprecht, K.W., K.G. Wulle, and H.L. Christl, [Applanation tonometry within medical diagnostic "check-up" programs (author's transl)]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1978. 172(3): p. 332-41.

- ↑ Segal, P. and J. Skwierczynska, Mass screening of adults for glaucoma. Ophthalmologica, 1967. 153(5): p. 336-48.

- ↑ Shiose, Y. and Y. Kawase, A new approach to stratified normal intraocular pressure in a general population. Am J Ophthalmol, 1986. 101(6): p. 714-21.

- ↑ Armaly, M.F., On the Distribution of Applanation Pressure. I. Statistical Features and the Effect of Age, Sex, and Family History of Glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol, 1965. 73: p. 11-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Leydhecker, W., K. Akiyama, and H.G. Neumann, [Intraocular pressure in normal human eyes]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd Augenarztl Fortbild, 1958. 133(5): p. 662-70.

- ↑ Sommer, A., et al., Relationship between intraocular pressure and primary open angle glaucoma among white and black Americans. The Baltimore Eye Survey. Arch Ophthalmol, 1991. 109(8): p. 1090-5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Drance, S.M., R.W. Morgan, and V.P. Sweeney, Shock-induced optic neuropathy: a cause of nonprogressive glaucoma. N Engl J Med, 1973. 288(8): p. 392-5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 The effectiveness of intraocular pressure reduction in the treatment of normal-tension glaucoma. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol, 1998. 126(4): p. 498-505.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Collaborative Normal-Tension Glaucoma Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol, 1998. 126(4): p. 487-97.

- ↑ 1. Salvetat ML, Pellegrini F, Spadea L, Salati C, Zeppieri M. Pharmaceutical Approaches to Normal Tension Glaucoma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023 Aug 17;16(8):1172. doi: 10.3390/ph16081172.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.0 21.1 1. Leung DYL, Tham CC. Normal-tension glaucoma: Current concepts and approaches-A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar;50(2):247-259. doi: 10.1111/ceo.14043. Epub 2022 Feb 7.

- ↑ 1. Fox AR, Fingert JH. Familial normal tension glaucoma genetics. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023 Sep;96:101191. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2023.101191. Epub 2023 Jun 22.

- ↑ 1. Mullany S, Xiao L, Qassim A, Marshall H, Gharahkhani P, MacGregor S, Hassall MM, Siggs OM, Souzeau E, Craig JE. Normal-tension glaucoma is associated with cognitive impairment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jul;106(7):952-956. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317461. Epub 2021 Mar 29.

- ↑ 1. Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, Sundquist K. Risk of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias in Persons With Glaucoma: A National Cohort Study. Ophthalmology. 2023 Oct 13:S0161-6420(23)00756-X. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.10.014. Epub ahead of print.

- ↑ Burk, R.O., et al., Are large optic nerve heads susceptible to glaucomatous damage at normal intraocular pressure? A three-dimensional study by laser scanning tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 1992. 230(6): p. 552-60.

- ↑ Tuulonen, A., et al., Optic disk cupping and pallor measurements of patients with a disk hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol, 1987. 103(4): p. 505-11.

- ↑ Vogel, W., et al., Delayed clearance of HBsAG after transplantation for fulminant delta-hepatitis. Lancet, 1988. 1(8575-6): p. 52.

- ↑ Buus, D.R. and D.R. Anderson, Peripapillary crescents and halos in normal-tension glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Ophthalmology, 1989. 96(1): p. 16-9.

- ↑ Yamazaki, Y., et al., Optic disc findings in normal tension glaucoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol, 1997. 41(4): p. 260-7.

- ↑ Anderson, D.R. and S. Normal Tension Glaucoma, Collaborative normal tension glaucoma study. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2003. 14(2): p. 86-90.

- ↑ Jump up to: 31.0 31.1 Gramer, E. and W. Leydhecker, [Glaucoma without ocular hypertension. A clinical study]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1985. 186(4): p. 262-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 32.0 32.1 Krupin T., et al., A randomized trial of brimonidine versus timolol in preserving visual function: results from the Low-Pressure Glaucoma Treatment Study. Am J Ophthalmol, 2011. 151(4): p. 671-81.

- ↑ Chuang LH, Koh YY, Chen HSL, Lo YL, Yu CC, Yeung L, Lai CC. Normal tension glaucoma in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: A structural and functional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Mar;99(13):e19468. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019468. PMID: 32221069; PMCID: PMC7220748.

- ↑ Lin PW, Friedman M, Lin HC, Chang HW, Wilson M, Lin MC. Normal tension glaucoma in patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. J Glaucoma. 2011 Dec;20(9):553-8. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181f3eb81. PMID: 20852436.

- ↑ Bilgin G. Normal-tension glaucoma and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a prospective study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014 Mar 10;14:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-14-27. PMID: 24612638; PMCID: PMC3975309.

- ↑ Leggewie B, Gouveris H, Bahr K. A Narrative Review of the Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Glaucoma in Adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 3;23(17):10080. doi: 10.3390/ijms231710080. PMID: 36077478; PMCID: PMC9456240.

- ↑ Phelps, C.D. and J.J. Corbett, Migraine and low-tension glaucoma. A case-control study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1985. 26(8): p. 1105-8.

- ↑ Flammer, J., K. Konieczka, and A.J. Flammer, The primary vascular dysregulation syndrome: implications for eye diseases. EPMA J, 2013. 4(1): p. 14.

- ↑ Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, Sundquist K. Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in Persons With Glaucoma: A National Cohort Study. Ophthalmology. 2023 Oct 13:S0161-6420(23)00756-X. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.10.014. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37839560.

- ↑ Hirooka K, Higashide T, Sakaguchi K, et al. Prevalence of Normal-Tension Glaucoma in Patients With Primary Aldosteronism. Am J Ophthalmol. Published online September 14, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2024.09.014

- ↑ Ho K, Bodi NE, Sharma TP. Normal-Tension Glaucoma and Potential Clinical Links to Alzheimer's Disease. J Clin Med. 2024;13(7):1948. Published 2024 Mar 27. doi:10.3390/jcm13071948

- ↑ Hollander, R., [The Influence of the Permeability of the Cell Membrane on TMPD Oxydase Activity (author's transl)]. Zentralbl Bakteriol Orig A, 1977. 237(2-3): p. 351-7.

- ↑ Hirooka, K., et al., Evaluation of peripapillary choroidal thickness in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol, 2012. 12: p. 29.

- ↑ Firat, P.G., et al., Evaluation of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, macula and ganglion cell thickness in amblyopia using spectral optical coherence tomography. Int J Ophthalmol, 2013. 6(1): p. 90-4.

- ↑ Zheng, Y., et al., Relationship of retinal vascular caliber with retinal nerve fiber layer thickness: the singapore malay eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2009. 50(9): p. 4091-6.

- ↑ Kim, J.M., et al., The association between retinal vessel diameter and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in asymmetric normal tension glaucoma patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2012. 53(9): p. 5609-14.

- ↑ Lee, J.Y., et al., Retinal vessel diameter in young patients with open-angle glaucoma: comparison between high-tension and normal-tension glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol, 2012. 90(7): p. e570-1.

- ↑ Mozaffarieh, M. and J. Flammer, New insights in the pathogenesis and treatment of normal tension glaucoma. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2013. 13(1): p. 43-9.

- ↑ Crawford Downs, J., M.D. Roberts, and I.A. Sigal, Glaucomatous cupping of the lamina cribrosa: a review of the evidence for active progressive remodeling as a mechanism. Exp Eye Res, 2011. 93(2): p. 133-40.

- ↑ 1. Wostyn P, Killer HE. Normal-Tension Glaucoma: A Glymphopathy? Eye Brain. 2023 Apr 6;15:37-44. doi: 10.2147/EB.S401306. PMID: 37056720

- ↑ Pan Y, Iwata T. Molecular genetics of inherited normal tension glaucoma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2024;72(Suppl 3):S335-S344. doi:10.4103/IJO.IJO_3204_23

- ↑ 1. Xie Y, Jiang J, Liu C, Lin H, Wang L, Zhang C, Chen J, Liang Y, Congdon N, Zhang S. Performance of a Glaucoma Screening Program Compared With Opportunistic Detection in China. J Glaucoma. 2023 Feb 1;32(2):80-84. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000002125. Epub 2022 Sep 9.

- ↑ 1. Seo SB, Cho HK. Deep learning classification of early normal-tension glaucoma and glaucoma suspects using Bruch's membrane opening-minimum rim width and RNFL. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 4;10(1):19042. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76154-7.

- ↑ Thickness Between Primary Open-angle Glaucoma, Normal Tension Glaucoma, and Normal Eyes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2024;7(4):359-371. doi:10.1016/j.ogla.2024.02.008

- ↑ Shih, C.Y., et al., Clinical significance of central corneal thickness in the management of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol, 2004. 122(9): p. 1270-5.

- ↑ Shetgar, A.C. and M.B. Mulimani, The central corneal thickness in normal tension glaucoma, primary open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. J Clin Diagn Res, 2013. 7(6): p. 1063-7.

- ↑ Tsai, J. and M.A. Karim, Current concepts in normal tension glaucoma. Review of Ophthalmology, 2006. 6(24).

- ↑ Tanna AP, Johnson M. Rho Kinase Inhibitors as a Novel Treatment for Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Ophthalmology. 2018 Nov;125(11):1741-1756. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.04.040. Epub 2018 Jul 12. PMID: 30007591; PMCID: PMC6188806.

- ↑ Thomas NM, Nagrale P. Rho Kinase Inhibitors as a Neuroprotective Pharmacological Intervention for the Treatment of Glaucoma. Cureus. 2022 Aug 26;14(8):e28445. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28445. PMID: 36176819; PMCID: PMC9512308.

- ↑ 1. Chihara E, Dimitrova G, Chihara T. Increase in the OCT angiographic peripapillary vessel density by ROCK inhibitor ripasudil instillation: a comparison with brimonidine. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018 Jul;256(7):1257-1264. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-3945-5. Epub 2018 Mar 8.

- ↑ 1. Kaneko Y, Ohta M, Inoue T, Mizuno K, Isobe T, Tanabe S, Tanihara H. Effects of K-115 (Ripasudil), a novel ROCK inhibitor, on trabecular meshwork and Schlemm's canal endothelial cells. Sci Rep. 2016 Jan 19;6:19640. doi: 10.1038/srep19640.

- ↑ El Mallah, M.K., et al., Selective laser trabeculoplasty reduces mean IOP and IOP variation in normal tension glaucoma patients. Clin Ophthalmol, 2010. 4: p. 889-93.

- ↑ Yang SA, Mitchell WG, Hall N, Elze T, Miller JW, Lorch AC, Zebardast N. Usage Patterns of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) Differ by Glaucoma Type: IRIS Registry Analysis 2013-2018. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022 Aug;29(4):443-451. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2021.1955391. Epub 2021 Jul 26. PMID: 34311672.

- ↑ Shuang-An Yang, William G Mitchell, Nathan Hall, Tobias Elze, Joan W Miller, Alice C Lorch & Nazlee Zebardast (2022) Usage Patterns of Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS) Differ by Glaucoma Type: IRIS Registry Analysis 2013–2018, Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 29:4,443-451, DOI: 10.1080/09286586.2021.1955391

- ↑ Schargus M, Theilig T, Rehak M, Busch C, Bormann C, Unterlauft JD. Outcome of a single XEN microstent implant for glaucoma patients with different types of glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020 Dec 17;20(1):490. doi: 10.1186/s12886-020-01764-8. PMID: 33334311; PMCID: PMC7745382.

- ↑ Oo HH, Hong ASY, Lim SY, Ang BCH. Angle-based minimally invasive glaucoma surgery in normal tension glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2024;52(7):740-760. doi:10.1111/ceo.14408

- ↑ Drance, S., et al., Risk factors for progression of visual field abnormalities in normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol, 2001. 131(6): p. 699-708.