Medial Canthal Tendon Avulsion

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Medial canthal tendon (MCT) avulsion refers to an eyelid injury where the entirety or part of the length of the eyelid involving the medial canthus has been torn from its normal anatomical position.[1]

Anatomy

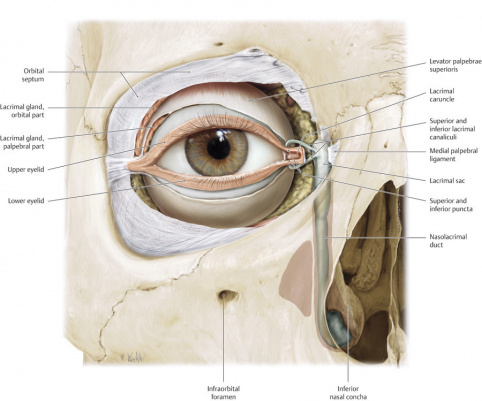

The medial canthal tendon closely surrounds the lacrimal drainage system. The MCT anatomy is complex and a thorough understanding of the anatomy allows for the surgeon the best opportunity for successful repair of the MCT. The MCT supports the medial canthus, positions the eyelid and the globe, and plays a role in the functioning and support of the lacrimal system.

The upper and lower eyelid puncta overlie the canaliculi, which travel 2mm vertically, then 8 to 10mm horizontally and medially within the orbicularis oculi muscle. In >90% of individuals, the upper and lower canaliculi converge to form a common canaliculus (about 3 to 5mm long) before entering the posterolateral wall of the nasolacrimal sac.

The MCT is closely related to the lacrimal drainage complex. The preseptal and pretarsal components of the orbicularis oculi fibers extend medially to form the MCT. The superior and inferior crura form the common medial canthal tendon, which then splits into anterior and posterior limbs (Figure 1). The anterior limb is considered the stronger limb of the two.[2] The anterior limb of the MCT passes in front of the nasolacrimal sac, inserting on to the frontal process of the maxillary bone and the anterior lacrimal crest. The anterior limb helps to keep the punctum in position.[3] The posterior limb of the MCT passes behind the lacrimal sac, inserting on the posterior lacrimal crest of the lacrimal bone. The posterior limb is considered to be a smaller limb.[4] It is traditionally thought that the posterior limb is important in maintaining the position of the medial eyelid so that it is well apposed to the globe.

Some sources have discussed a superior limb of the MCT and that the MCT is a tripartite structure with anterior, posterior, and superior limbs.[3] In cadaver dissections initially described by Jones et al[5] and then later Anderson[4], there is a superior branch of the MCT which inserts on the frontal bone. It is thought that this superior limb, in addition to the anterior limb, firmly supports the eyelid from malposition. Anderson describes that posterior portion of the MCT as a very thin and weak structure, and it is likely that the superior branch plays a larger role in supporting the position of the eyelid relative to the posterior limb.[4]

In other cadaver studies performed by Robinson et al[2] and Poh et al[6], the posterior limb was not able to be isolated. Robinson et al[2] and Poh et al[6] have proposed that the posterior branch does not actually exist, and that the fibrous condensation inserting into the posterior lacrimal crest is actually Horner’s (or Horner-Duverney's) muscle.

Etiology

Damage to the eyelid commonly occurs secondary to blunt trauma, animal (dog) bites, motor vehicle collisions, falls, or assault with horizontal or lateral traction to the eyelid leading to shearing of the lid generally medially. This is especially common in naso-orbitoethmoidal fractures. Additionally, iatrogenic injuries can occur during oculoplastic or otolaryngology surgery, such as during dacryocystorhinostomy or after surgical resection of periocular tumors. These injuries can cause avulsion at the posterior limb of the medial canthal tendon, which is relatively weak against lateral tractional force.[7] The lower eyelid is more commonly damaged than the upper eyelid.[8] Damage to the medial canthal tendon can also occur in malignant tumor resections.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a MCT avulsion is a clinical diagnosis. Generally it is seen with lacerations of the medial lower eyelid, though fractures can impact the MCT without a laceration. Concurrent injury of the canaliculi is also common and should be carefully evaluated.

History

Asking a careful history with a thorough understanding of the mechanism of injury is important, as there may be damage to deeper or underlying structures. Any injury to the upper medial face (including the brow, nose, or cheek) should raise suspicion for possible MCT trauma.

Physical exam

For a patient with suspicion of injury to the medial canthal tendon, a complete ocular exam to check for any kind of globe injury is first necessary. Given the close proximity to the lacrimal drainage system, it is common for concurrent injury to both the canaliculi and MCT. To examine the lacrimal drainage system, it is important to gently examine with probing (usually with a Bowman probe) and/or irrigation to check lacrimal drainage function.

Next, the integrity of the superior and inferior limbs of the medial canthal tendon can be assessed using toothed forceps and gently tugging away from the injury while palpating the insertion of the tendon.[9] Close attention should be paid to the position of the punctum and whether or not it is displaced, which can indicate if the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon is attached. To evaluate the extent of the avulsion, evaluate the posterior tendinous attachment to the posterior lacrimal crest. If there is rounding of the medial canthal angle, acquired telecanthus, or horizontal shortening of the palpebral aperture, there should be a high suspicion for medial canthal tendon avulsion.[10]

To prepare for repair, it is important to evaluate the quality of adjacent skin as well as the laxity of adjacent tissue.

Signs / Symptoms

Patients may present with malpositioned eyelids, telecanthus, epiphora (if the canalicular system is involved), pain, decreased vision (given eyelid position).

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of a medial canthal injury is largely clinical and dependent on the physical exam (see above).

Diagnostic procedures

Computer tomography (CT) imaging without intravenous contrast is the best method to evaluate the extent of the injury and note if there is a concurrent bony injury. Contrast is not needed to identify fractures on a CT scan. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is contraindicated as the initial study in cases of trauma given concern for any ferromagnetic material; furthermore, it is time consuming and expensive relative to CT imaging.

Management

General treatment

Prompt evaluation of globe and surrounding structures by an eye specialist, such as an ophthalmologist or ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgeon, is necessary in cases of trauma. The main goal of restoration of the medial canthus is to retain normal eyelid function, support the lacrimal drainage system, and protect the globe.

In cases of trauma, patients need updated tetanus vaccination if they have not received it within the last ten years. Routine coverage with oral antibiotics is controversial. In cases of bite wounds which are typically polymicrobial infections, antibiotic coverage with Augmentin is generally recommended.

Immediate surgical intervention is not necessarily required in cases of trauma. Repair within the first 24-48 hours is ideal, though there has been evidence that there can still be acceptable outcomes even beyond 48 hours. Repair is performed in an operating room with general anesthesia.

Surgery

First, if the canalicular system is involved, then intubation is undertaken with bicanalicular crawford-style lacrimal stents, mono-crawford, or mini monoka stents, as described here. The bicanalicular stent provides posteromedial traction, which helps for reapproximation of the medial canthal tendon complex.

Once intubation of the canalicular system has been performed (if the lacrimal system is involved), then the MCT should be repaired next. Traditionally canthopexy has been advocated for surgical repair of the MCT which involves subperiosteal exposure and fixation to the bony attachment.[7] If the MCT is severed and both ends of the tendon can be identified, a non-absorbable suture such as 4-0 polyester suture can be placed using a horizontal mattress. If the periosteum is intact but the distal end of avulsed MCT cannot be identified, a 5-0 braided multifilament absorbable suture can be placed through the periosteum of the medial wall and the canthal tendon.[11] If there is complete avulsion of the MCT, then a microplate can be used to fixate the MCT to bone.[11] A transnasal wire can also be utilized to achieve satisfactory positioning.[12] Use of a transnasal wire requires surgical access to the normal contralateral medial canthus. A burr is used to make a 5 to 7mm hole superiorly and posteriorly to the horizontal insertion of the MCT, and a transnasal wire is passed through.

However the above technique has been noted to be surgically demanding and time consuming. The periosteum is very thin over the posterior lacrimal crest which can make repair technically difficult. Furthermore, the lacrimal sac is encased in fascia in close proximity and is thus at high risk of accidental damage during repair.[3]Complications with transnasal wiring including medial canthal drift, wire extrusion, and contralateral orbital bone fracture from the transnasal wire pressure.[13]

Other techniques have been described for reattachment of the MCT to the orbital medial wall. Okazaki et al.[14] describes the Mitek anchor system as an alternative to medial canthal tendon fixation. This technique uses a screw hole that is drilled into the orbital medial wall, and a suture is threaded into the head of the anchoring device to push the anchor into the hole directly. The sutures are then sewn to the stump of the medial canthal tendon for fixation onto the bone.[14] In cadaver studies, it has been described to have 97% of the holding strength of the contralateral MCT.[15] Potential drawbacks to this technique is that the anchor can be difficult to remove .[16] Kakudo et al.[16] describes another anchoring system called the Caraji Anchor Suture System. This Caraji Anchor Suture system fixates the MCT by using self-tapping screws and an exclusive driver. The self-tapping screw is able to create holes for fixation and the bone fixation point can be corrected if needed.[16]

Turgot et al[17] described utilization of a unitransnasal canthoplasty to repair the MCT. This technique creates 2 drill holes in the periosteum matching the MCT attachment point. 2 nonabsorbable sutures were passed through these drill holes and tied from the ipsilateral nasal ostium, and then needles were passed through the canthal tendon. Advantages to this technique is that it is relatively easy, cheap, does not injure the opposite nasal bone, and does not require additional equipment. However, this study only included two patients, though both patients who underwent this procedure had good surgical outcomes.[17]

Other methods propose that MCT reconstruction may not necessarily be needed if the canalicular system is repaired. In cases of combined eyelid avulsion and canalicular injury, placement of a bi-canalicular Crawford stent without reconstruction of the MCT has been noted to create good tissue alignment and cosmetic outcome.[3] Intubation with the crawford stent allows for traction medially and posteriorly to help maintain the positioning of the eyelid without the placement of a medial traction suture (35 out of 37 patients in this study).[3] Good outcomes were noted in this study with little epiphora and ideal cosmetic results.

Surgical follow-up

Following repair of a canalicular laceration, the stent is kept in for a minimum of six weeks, though can be left for longer (4-6 months) if it is not causing any issues or discomfort to the patient. The stent can be removed from a nasal or ocular approach, depending on the stent used and if there was fixation such as to the nasal mucosa or through the inferior turbinate.

After repair, the patient is typically given antibiotic ointment and possibly oral antibiotics if needed. Patients are generally seen at post-operative week 1, week 4-6, and more long-term follow-up as needed. Patients can be expected to experience some mild bruising, swelling, and pain postoperatively and may have initial epistaxis.

Complications

It is important to discuss possible complications with patients that can occur post surgical repair. As with any ophthalmic procedure, there is risk of bleeding, infection, pain, or loss of vision. Other possible complications more specific to MCT repair include scarring due to poor healing, poor cosmetic outcomes, telecanthus, epiphora, ectropion, stenosis of the nasolacrimal system, or iatrogenic trauma to the undamaged canaliculus. Patients with postoperative complications may require additional surgery.

Prognosis

In general, most patients who undergo prompt surgical repair of MCT avulsions have good functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Additional Resources

1) Freitag SK, Lee NG, Lefebvre DR, Yoon MK. Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery: Tricks of the Trade. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc. 2020

References

- ↑ Goldberg SH, Bullock JD, Connelly PJ. Eyelid avulsion: a clinical and experimental study. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8(4):256–61.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Robinson TJ, Strac MF. The anatomy of the medial canthal ligament. Br J Plast Surg. 1970;1:1-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Tint NL, Alexander P, Cook AE, Letherbarrow B. Eyelid avulsion repair with bi-canalicular silicone stenting without medial canthal tendon reconstruction. Br J ophthalmol. 2011; 95:1389-1392.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Anderson RL. Medial Canthal Tendon Branches Out. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(11):2051–2052. doi:10.1001/archopht.1977.04450110145019

- ↑ Jones LT, Reeh MJ, Wirtschafter JD: Ophthalmic Anatomy. Rochester, NY, American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology, 1970, pg 39-48.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Poh E, Kakizaki H, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Anatomy of medial canthal tendon in Caucasians. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40(2):170-173. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02657.x

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Zide BM, McCarthy JG. The medial canthus revisited: an anatomical basis for canthopexy. Ann Plast Surg 1983;11:1e9.

- ↑ Subramanian N. Reconstructions of eyelid defects. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011 Jan;44(1):5–13.

- ↑ •Korn, Bobby S et al. “BCSC Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System.” San Francisco, CA. American Academy of Ophthalmology 2023.

- ↑ Zide BM, McCarthy JG. The medial canthus revisited: an anatomical basis for canthopexy. Ann Plast Surg 1983;11:1e9.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Godfrey KJ, Dubnar KE, Lelli GJ. Canalicular Laceration and Medial Canthal Tendon Avulsion Repair. TEXTBOOK ADD

- ↑ Mustarde JC. Repair and Reconstruction in the Orbital Region: A Practical Guide. 1966:London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone, Publishing; 292–298.

- ↑ Kosins AM, Kohan E, Shajan J, Jaffurs D, Wirth G, Paydar K. Fixation of the medial canthal tendon using the Mitek anchor system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6):309e-310e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f63f52

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Okazaki M, Akizuki T, Ohmori K. Medial canthoplasty with the Mitek anchor system. Ann Plast Surg 1997;38:124–8.

- ↑ Dagum BD, Antonyshyn O, Hearn T. Medial canthopexy: an experimental and biomechanical study. Ann Plast Surg 1995;35:262-265.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kakudo N, Takegawa M, Hihara M, Morimoto N, Masuoka H, Kusumoto K. Reconstruction of Medial Canthal Tendon Using Novel Suture Anchoring System: A Case Report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(10):e1908. Published 2018 Oct 15. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000001908

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Turgut G, Ozkaya O, Soydan AT, Baş L. A new technique for medial canthal tendon fixation. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(4):1154-1158. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181764b6c