Kyrieleis Plaques

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Kyrieleis plaques are also referred to as “Kyrieleis vasculitis”, “Kyrieleis arteriolitis”, “nodular periarteritis”, “segmental retinal periarteritis” or “segmental retinal arteritis” in the literature.

Disease

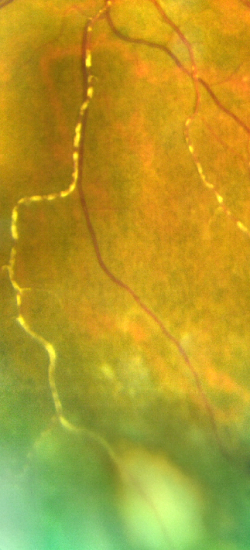

Kyrieleis plaques represent a rare fundus examination finding, first described in an eye with presumed tuberculous uveitis by Werner Kyrieleis, in 1933.[1] They appear as multiple, segmental yellowish-white lesions within the retinal arteries, in a beaded pattern[2] [3] [4] reported both in infectious and non-infectious inflammatory posterior uveitis. These reversible segmented white deposits are not intraluminal or extravasal, but within the vessel walls. [5][6]

Epidemiology

Kyrieleis arteritis is regarded as a rare clinical entity. [7] However, some defend that this disorder is way more common than the literature suggests, as it may be considerably underreported.[8]

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The etiology of Kyrieleis plaques is unknown but they always reflect severe intra-ocular inflammation.[4] They have been typically associated with infectious posterior uveitis, and Toxoplasma gondii is the most frequent reported cause. Treponema pallidum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Varicella-Zoster Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus- 1 and 2, and Rickettsia conorii are other common agents.[2] [3] [4] [7] [8][9] [10] [11] [12] Kyrieleis arteritis in association with Behçet disease has also been described.[7] Kyrieleis plaques are also described as clinical feature of Brolucizumab-Associated Retinal Vasculitis and Intraocular Inflammation[13] The pathophysiology of these plaques is not completely known, and there is still a lot to discover about the composition of the whitish deposits and their exact location within the arteries.[4] [7] Various hypotheses have been proposed, though. Griffin and Bodian, in 1959, speculated that the plaques represented exudates migration from an adjacent retinochoroiditis focus to the periarterial sheaths.[14] In 1971, Orzalesi and Ricciardi hypothesized that these deposits were constituted of cellular and inflammatory material within the arterial walls.[15] Wise proposed that they were arteriosclerosis lesions.[16] Recently, a study based on multimodal retinal imaging, suggested that the plaques do not represent periarterial or endoluminal injury, but the involvement of the arterial endothelium.[4]

Diagnosis

Like other forms of retinal vasculitis, the diagnosis of Kyrieleis is clinical, based on the fundoscopic examination, and supported by ancillary tests namely fluorescein angiography (FA), indocyanine green (ICG) angiography, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and optical coherence tomography (OCT).[4]

Fundoscopy

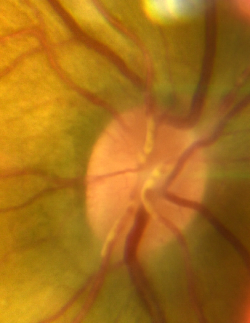

On fundus exam, Kyrieleis plaques appear as focal yellowish-white deposits, looking like atheromatous plaques, segmentally distributed along the retinal arteries.[3] [4] [7] [8][17] As previously mentioned, these plaques always occur in association with intra-ocular inflammation, and typically, an active focus of chorioretinitis is present near the affected arteries.[4] Sometimes, the plaques can only be visible once the severe intraocular inflammation has resolved.[11] Kyrieleis plaques involve exclusively the arterial and glisten and often look calcific like lesions.[4] [7]

Fluorescein Angiography (FA)

Fluorescein angiography findings in Kyrieleis arteritis are very distinctive because there is no evidence of occlusive phenomenon, nor leakage of fluorescein dye.[4] [7] Eventually, this absence of vascular leakage excludes a transmural involvement of the artery wall, limiting the inflammatory process exclusively to the endothelium itself.[4] Therefore, Pichi et al suggest that the term “endothelitis” would be more suitable to name these plaques.[4] This same group recently reported that Kyrieleis plaques were hypofluorescent in early frames, with increasing hyperfluorescence in later angiographic frames with no leakage of the dye.[4] Others, on the other hand, stated that the retinal arteries containing the plaques had a completely normal angiographic behavior throughout all phases of the exam.[3][9]

Indocyanine Green (ICG) Angiography

According to Pichi et al, ICG angiography is the most precise imaging modality to reveal even subtle Kyrieleis plaques.[4] Due to its amphiphilic nature, the ICG easily binds to the inflammatory molecules that compose the plaque, displaying well-delineated hyperfluorescence during the whole exam.[4]

Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF)

Kyrieleis plaques appear hyperautofluorescent, potentially due to selective inflammation of the vascular endothelium.[4]

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

SD-OCT scans show hyperreflectivity of the artery wall at the sites of Kyrieleis plaques.[4] Tsui and co-authors demonstrated on OCT angiography narrowing of the intraluminal flow signal in the presence of these plaques. [18]

Differential diagnosis

The glistening, yellowish-white, calcific-like appearance typical of Kyrieleis plaques can be ophthalmoscopically difficult to differentiate from fluffy perivascular sheathing or cuffing, characteristic of other forms of retinal vasculitis, especially in cases of severe intraocular inflammation where both finds can coexist.[3] [8] [9] In this scenario, it might be helpful to bear in mind that Kyrieleis plaques affect exclusively the retinal arteries.[4] [7] Besides, they are limited to the endothelium and do not extend outside the vessel wall, and thus, do not leak in FA, in contrast to areas of vascular sheathing.[4] [8]

Kyrieleis plaques can also be misdiagnosed as retinal emboli or atheromatous plaques.[11] Again, FA findings can help in this differential diagnosis as it presents with normal arterial filling, with no evidence of lumen obstruction or retinal non-perfusion.[4] [7] [9] [11]

Management

The management of Kyrieleis arteritis depends on the underlying etiology. The control of intraocular inflammation is the primary goal. The plaques resolve as vitritis improves.

Prognosis

Although associated with severe ocular inflammation, Kyrieleis plaques are a benign finding, that does not worsen the prognosis of the underlying uveitis.[4][19] Generally, with adequate treatment, there is a complete disappearance of the plaques (usually after the resolution of vitritis) without sequelae 5. However, the plaques can persist long after the resolution of chorioretinitis and discontinuation of therapy.[20]

References

- ↑ Kyrieleis W. [Discontinuous reversible arteriopathy in uveitis]. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Ophthalmol. 1950;150(5-6):600-13.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Francés-Muñoz E, Gallego-Pinazo R, López-Lizcano R, García-Delpech S, Mullor JL, Díaz-Llopis M. Kyrieleis' vasculitis in acute retinal necrosis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:837-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Goel N, Sawhney A. Kyrieleis plaques associated with Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 acute retinal necrosis. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2016;30(2):144-7.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 Pichi F, Veronese C, Lembo A, Invernizzi A, Mantovani A, Herbort CP, et al. New appraisals of Kyrieleis plaques: a multimodal imaging study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(3):316-21.

- ↑ Tadepalli A, Harewood J, Ketner DS. Kyrieleis plaques: recognising a rare presentation of ocular inflammation. Clin Exp Optom. 2024 Jan 8:1-3.

- ↑ Mahjoub A, Ben Abdesslem N, Zaafrane N, Sellem I, Sahraoui F, Nouri H, Hadj RB, Ben Alaya A, Krifa F, Hachemi M. Kyrieleis arteritis associated with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 May 17;78:103802.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Chazalon E, Conrath J, Ridings B, Matonti F. [Kyrieleis arteritis: report of two cases and literature review]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2013;36(3):191-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Patel A, Pomykala M, Mukkamala K, Gentile RC. Kyrieleis plaques in cytomegalovirus retinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2011;1(4):189-91.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Empeslidis T, Konidaris V, Brent A, Vardarinos A, Deane J. Kyrieleis plaques in herpes zoster virus-associated acute retinal necrosis: a case report. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(9):1110-2.

- ↑ Krishnamurthy R, Cunningham ET, Jr. Atypical presentation of syphilitic uveitis associated with Kyrieleis plaques. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(8):1152-3.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Witmer MT, Levy-Clarke GA, Fouraker BD, Madow B. Kyrieleis plaques associated with acute retinal necrosis from herpes simplex virus type 2. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2011;5(4):297-301.

- ↑ Khairallah M, Ladjimi A, Chakroun M, Messaoud R, Yahia SB, Zaouali S, et al. Posterior segment manifestations of Rickettsia conorii infection. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(3):529-34.

- ↑ Baumal, C. R., Spaide, R. F., Vajzovic, L., Freund, K. B., Walter, S. D., John, V. J., … Albini, T. A. (2020). Retinal vasculitis and intraocular inflammation after intravitreal injection of brolucizumab. Ophthalmology. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.017

- ↑ Griffin AO, Bodian M. Segmental retinal periarteritis; a report of three cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 1959;47(4):544-8.

- ↑ Orzalesi N, Ricciardi L. Segmental retinal periarteritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72(1):55-9.

- ↑ Wise GN. Ocular periarteritis nodosa; report of two cases. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1952;48(1):1-11.

- ↑ Khadamy J (October 15, 2023) Atypical Ocular Toxoplasmosis: Multifocal Segmental Retinal Arteritis (Kyrieleis Arteritis) and Peripheral Choroidal Leision. Cureus 15(10): e47060. doi:10.7759/cureus.47060

- ↑ Tsui E., Leong B.C.S., Mehta N., Gupta A., Goduni L., Cunningham E.T., Jr., Freund K.B., Lee G.D., Dedania V.S., Yannuzzi L.A., Modi Y.S. Evaluation of segmental retinal arteritis with optical coherence tomography angiography. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2021 Nov 1;15(6):688–693.

- ↑ Meier PG, Herbort CP, Jr., Wolfensberger TJ. Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography for the Characterization of Kyrieleis Exudates Involving Both the Fovea and Retinal Vessels. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2016;233(4):545-6.

- ↑ Kaza H, Patel A, Pathengay A. Persistence of Kyrieleis arteriolitis in bilateral acute retinal necrosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(9):1974.