Foster-Kennedy vs Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

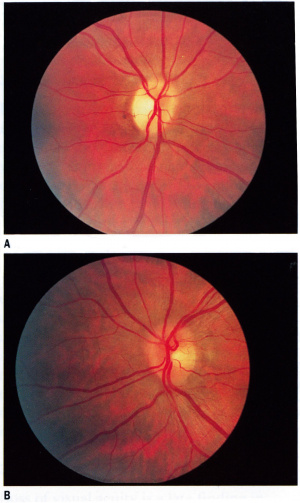

Foster-Kennedy Syndrome is characterized by unilateral visual loss with a compressive optic atrophy in one eye and contralateral papilledema caused by increased intracranial pressure. The same ophthalmoscopic features however can be seen in the pseudo-Foster-Kennedy Syndrome. The differentiating and distinguishing features of both conditions are detailed below.

Disease Entity

Foster-Kennedy syndrome

Types

Foster-Kennedy Syndrome that presents with optic atrophy in one eye and papilledema in the contralateral eye is the most well-known type of Foster-Kennedy Syndrome and is also known as type 1 Foster-Kennedy Syndrome, which is commonly secondary to a mass compression(frequently meningioma). [1][2][3] Besides, type 1 Foster-Kennedy Syndrome, there are two other types of true Foster-Kennedy Syndrome. Type 2 Foster-Kennedy Syndrome is bilateral papilledema with unilateral optic atrophy. Type 3 Foster-Kennedy Syndrome is bilateral papilledema developing bilateral optic atrophy. Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy Syndrome presents similarly to type 1 Foster-Kennedy Syndrome except, it describes a non-mass lesions or mass without direct compression to the locations above (ie gyrus rectus [4] Few of the etiologies include, among others[5] [6] [7] [8]:

- NAION- bilateral but sequential

- IIH (idiopathic intracranial hypertension) worse in one eye

- Neurosyphilis

Etiology

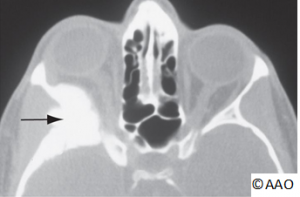

Foster-Kennedy Syndrome is characterized by the compression of the ipsilateral optic nerve by an intracranial mass, often an anterior cranial fossa meningioma , or other such as frontal lobe, olfactory groove, sphenoid wing. When the intracranial mass is large enough however to elevate intracranial pressure, contralateral optic nerve edema results.[9] An atrophic optic nerve is no longer able to manifest the optic disc edema and therefore only contralateral optic nerve edema is seen. [10] In some cases, there are other neurological findings denoting tumor extension.[11]

Risk Factors

The classical causes of a true Foster-Kennedy Syndrome are frontal lobe, olfactory groove, or sphenoid wing meningiomas.[12] Some risk factors for meningiomas include:

- Previous radiation exposure to the head

- Neurofibromatosis type 2

- Female gender (possible role of hormones)[13]

- Body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and weight.[14]

General Pathology

Origin from meningothelial (arachnoid) cells with variable histological appearance from epithelial to mesenchymal. A uniform distribution of cells demonstrating polygonal epithelial-like to spindle or fusiform shape.

Diagnosis

History

- Progressive loss of vision in one eye secondary to compressive optic atrophy

- Optic atrophy is a result of axon compression or ischemia secondary to vascular compression [15]

- Visual findings of papilledema in contralateral eye (e.g. enlarged blind spot) secondary to elevated intracranial pressure [15]

- Symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure (e.g., headache diplopia, nausea and vomiting)[16]

- Family members may report personality changes

Symptoms

- Progressive visual loss

- Headache

- Nausea/vomiting

- Anosmia

- Diplopia

- Emotional lability

Physical examination

- Visual acuity is variably affected in the ipsilateral eye with optic atrophy

- A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) is typically present in the eye with optic atrophy[17]

- Visual acuity is typically spared in the contralateral eye until late.

- Variable visual field loss in the affected eye in an optic neuropathy pattern with visual field loss of papilledema in the fellow eye (e.g., enlarged blind spot, nerve fiber layer loss)

- Diplopia from a non-localizing sixth nerve palsy due to increased intracranial pressure

- Fundus exam showing ipsilateral optic atrophy and contralateral papilledema

- Proptosis may be present if orbital involvement occurs from tumor

Clinical diagnosis

Neuroimaging studies should be performed for patients suspected of having the Foster Kennedy syndrome (e.g., head and orbital CT or MRI with and without contrast).

Differential diagnosis

- Frontal lobe parenchymal tumors[10]

- Meningioma (e.g., olfactory, frontal, sphenoid wing)[18]

- Intracranial Meningiomatosis[19]

- Pseudo-pseudo Foster Kennedy syndrome (PPFKS)

Management

General treatment

The primary treatment of meningiomas is surgical resection.

Medical therapy

- Initial treatment for symptomatic brain tumors include corticosteroids, which may reduce peritumoral edema and intracranial pressure.[18]

- If a non-surgical intervention is preferred, stereotactic radiotherapy and radiosurgery can be used in patients. In the elderly (classified >70), stereotactic radiotherapy of benign meningiomas could be a favorable option as neurosurgery can be often correlated with some mortality at that age range.[20]

- Chemotherapy and hormonal treatments have not been very successful in meningiomas.[21]

- Hydroxyurea has been found anecdotally to be modestly beneficial but has been used for unresectable tumors and large residual tumors.[21]

Surgery

If the patient is a surgical candidate then resection is generally the best treatment option to reduce mass effect and relieve elevated intracranial pressure.[21] Prior to surgery, embolization of vascular tumors can reduce intraoperative bleeding and limit post-operative complications.

Surgical follow up

Radiotherapy can be used for residual or reoccurring tumor post-surgery

Prognosis

Variable

Disease Entity

Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy syndrome

Disease

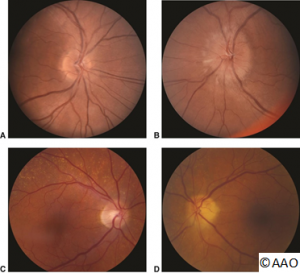

Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy Syndrome (PFKS) is characterized ophthalmoscopically by unilateral optic atrophy with contralateral optic disc edema. These findings can mimic the true Foster-Kennedy Syndrome, but clinical features and presentation often can distinguish the two entities.

Etiology

The most common etiology for PFKS is bilateral sequential anterior ischemic optic neuropathies (AION), either arteritic (AAION) or nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). NAION is more commonly seen.[15] PFKS can be noted in these patients as new, acute visual loss and optic disc swelling in one eye with prior visual loss and secondary optic disc atrophy resulting from a previous ischemic event in the other eye (AION).

Other causes of PFKS are seen in diseases other than AION that also cause optic atrophy from a prior event with an acute episode of optic disc edema (e.g., prior papillitis and secondary optic atrophy from infectious, inflammatory, infiltrative, or other causes).

Risk Factors

Risk Factors for NAION:

- Hypertension

- Diabetes Mellitus

- High cholesterol

- History of smoking

- Sleep Apnea Syndrome[22]

Primary prevention

Primary prevention of NAION includes control of vasculopathic risk factors (e.g., blood pressure, blood sugars, and cholesterol levels).

Diagnosis

History

Sudden loss of vision in one eye with optic disc edema in the setting of prior optic neuropathy in the fellow eye

Physical examination

- Variable visual acuity and/or visual field loss in each eye

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) may be present in worse affected eye

- Optic atrophy in prior affected eye

- Optic disc edema (sector or diffuse) in acutely affected eye

Diagnostic procedures

- Evaluation and treatment of underlying etiology (e.g., NAION) in typical PFKS

- Atypical cases should undergo consideration for neuroimaging (CT and MRI) to rule out intracranial mass, optic nerve enhancement

- Consider Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) in elderly patients

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of the PFKS therefore includes any cause of prior optic atrophy with contralateral acute optic nerve swelling:

- Inflammatory or demyelinating optic neuritis[15]

- Traumatic optic neuropathy

- Bilateral orbital or intracranial compressive optic neuropathy[23]

- True Foster-Kennedy Syndrome

- NAION, AAION, Diabetic papillopathy[24]

- Pseudo-pseudo Foster Kennedy syndrome (PPFKS)

General treatment

Medical therapy

Medical therapy: Depends on etiology

- Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: high dose systemic corticosteroid therapy, prednisone therapy[25]

- Optic neuritis: intravenous methylprednisone followed by oral prednisone could be considered[26]

- Treatment of underlying cause of the optic neuropathy

Medical follow up

Follow-up is key to ensure that the optic disc edema resolves[15]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends heavily on the underlying cause of PFKS

Additional Resources

Acknowledgements All images: courtesy of © 2017 American Academy of Ophthalmology

References

- ↑ Musa MJ, Zeppieri M. Foster Kennedy Syndrome, NIH STAT pearls, July 1, 2022 accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK582149/

- ↑ Sadun A and Agarwal M. Tipical diagnosis of acquired optic nerve disorders. In: Miller N, Biousse V, Newman N, Kerrison J, ed. Walsh and Hoyt's Clinical Neuro-ophthalmology. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:228-229.

- ↑ Lai A, Chiu S, Lin I, Sanders M. Foster Kennedy syndrome: Now and then. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2014;34:92-94.

- ↑ Desai N, Yong RL, Doshi A, Rucker JC. Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy syndrome with optic nerve compression by the gyrus rectus. Neurology. 85 (4): 385.

- ↑ Micieli J, Al-Obthani M, Sundaram A. Pseudo-foster kennedy syndrome due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(4):e99-e102

- ↑ Visa Reñé N, Paredes Carmona F. Pseudo-Foster Kennedy syndrome due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Short communication. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. Dec 2019. 94(12): 598-601 DOI: 10.1016/j.oftal.2019.09.006

- ↑ Bansal S, Dabbs T, Long V. Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome due to unilateral optic nerve hypoplasia: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2: 86. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-2-86

- ↑ Gelwan MJ, Seidman M, Kupersmith MJ. Pseudo-pseudo-Foster Kennedy syndrome. Journal of clinical neuro-ophthalmology. 8 (1): 49-52.

- ↑ Liu, Grant T., Nicholas J. Volpe, and Steven L. Galetta. Neuro-ophthalmology: Diagnosis and Management. N.p.: Saunders, Elsevier, 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Massey, E. W., and B. Schoenberg. "Foster Kennedy Syndrome." Archives of Neurology 41.6 (1984): 658-59.

- ↑ Mahjoub Y, Wan M, Subramaniam S. Pearls & Oy-sters: Trigeminal Cystic Schwannoma Presenting With Foster Kennedy Syndrome, Sixth Nerve Palsy, and Focal Seizures. Neurology. 2023;100(12):587-590. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000201700

- ↑ Deshmukh S, Das D, Bhattacharjee H, Kuri GC, Magdalene D, Gupta K, Multani PK, Paulbuddhe V, Dhar S. Profile of brain tumors having ocular manifestations in a Tertiary Eye Care Institute: A retrospective study. TNOA J Ophthalmic Sci Res [serial online] 2018 [cited 2018 Sep 2];56:71-5. Available from: http://www.tnoajosr.com/text.asp?2018/56/2/71/238494

- ↑ Sun, Tao, et al. “An Integrative View on Sex Differences in Brain Tumors.” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, vol. 72, no. 17, 2015, pp. 3323–3342.

- ↑ Michaud, D. S., G. Bove, V. Gallo, B. Schlehofer, A. Tjonneland, A. Olsen, K. Overvad, C. C. Dahm, B. Teucher, H. Boeing, A. Steffen, A. Trichopoulou, C. Bamia, A. Kyrozis, C. Sacerdote, C. Agnoli, D. Palli, R. Tumino, A. Mattiello, H. B. Bueno-De-Mesquita, P. H. M. Peeters, A. M. May, A. Barricarte, M.-D. Chirlaque, M. Dorronsoro, M. Jose Sanchez, L. Rodriguez, E. J. Duell, G. Hallmans, B. S. Melin, J. Manjer, S. Borgquist, K.-T. Khaw, N. Wareham, N. E. Allen, R. C. Travis, I. Romieu, P. Vineis, and E. Riboli. "Anthropometric Measures, Physical Activity, and Risk of Glioma and Meningioma in a Large Prospective Cohort Study." Cancer Prevention Research 4.9 (2011): 1385-392.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Vickers, Laura A., MD, M. Tariq Bhatti, MD, and Mays A. El-Dairi, MD. "Diagnose and Manage Pseudo–Foster Kennedy Syndrome." EyeNet Magazine Jan. 2014: n. pag.

- ↑ Halpern, Jesse, et al. Neuro-Ophthamology Problem-Solving: a Practical and User-Friendly Guide. Plural Publishing, 2009.

- ↑ Pastora-Salvador, N., and J. Peralta-Calvo. "Foster Kennedy Syndrome: Papilledema in One Eye with Optic Atrophy in the Other Eye." Canadian Medical Association Journal 183.18 (2011): 2135.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lotfipour, Shahram, Kris Chiles, J. Akiva Kahn, Tareg Bey, and Scott Rudkin. "An Unusual Presentation of Subfrontal Meningioma: A Case Report and Literature Review for Foster Kennedy Syndrome." Internal and Emergency Medicine 6.3 (2010): 267-69.

- ↑ Acebes, X MD; Arruga, J MD, PhD; Acebes, J J MD, PhD; Majos, C MD, PhD; Muñoz, S MD; Valero, Isaac Alarcon MD. Intracranial Meningiomatosis Causing Foster Kennedy Syndrome by Unilateral Optic Nerve Compression and Blockage of the Superior Sagittal Sinus. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 29(2):p 140-142, June 2009. | DOI: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3181a63583

- ↑ Fokas, Emmanouil, Martin Henzel, Gunar Surber, Klaus Hamm, and Rita Engenhart-Cabillic. "Stereotactic Radiotherapy of Benign Meningioma in the Elderly: Clinical Outcome and Toxicity in 121 Patients." Radiotherapy and Oncology 111.3 (2014): 457-62.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Alexiou, George A., Pinelopi Gogou, Sofia Markoula, and Athanasios P. Kyritsis. "Management of Meningiomas." Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 112.3 (2010): 177-82.

- ↑ Mojon, Daniel S. “Association Between Sleep Apnea Syndrome and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy.” Archives of Ophthalmology, vol. 120, no. 5, Jan. 2002, p. 601.

- ↑ Desai, Ninad, et al. “Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy Syndrome with Optic Nerve Compression by the Gyrus Rectus.” Neurology, vol. 85, no. 4, 2015, pp. 385–385.

- ↑ Ap, Vignesh. “Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome Due to Diabetic Papillopathy.” Advances in Ophthalmology & Visual System, vol. 2, no. 4, Dec. 2015.

- ↑ Hayreh, Sohansingh. “Management of Ischemic Optic Neuropathies.” Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 59, no. 2, 2011, p. 123.

- ↑ Atkins, Edward J., et al. “Management of Optic Neuritis in Canada: Survey of Ophthalmologists and Neurologists.” The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, vol. 35, no. 02, 2008, pp. 179–184.