Pseudo-Pseudo Foster Kennedy Syndrome vs Foster Kennedy Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Pseudo-pseudo Foster Kennedy syndrome (PPFKS) describes a rare condition that is characterized by a combination of ischemic optic neuropathy and papilledema; importantly, these findings are a result of two separate pathologies. Similar ophthalmoscopic features can be seen in Foster-Kennedy Syndrome. The differentiating and distinguishing features of both conditions are detailed below.

Disease Entity

Disease

Foster-Kennedy Syndrome (FKS) is a combination of optic atrophy and papilledema, typically manifesting as progressive vision loss. There are three types of FKS. Type 1, the most recognized type, is characterized by ipsilateral optic atrophy and contralateral papilledema due to intracranial mass compressing one optic nerve and contralateral papilledema due to increase intracranial pressure.[1]

The pseudo-FKS is typically a bilateral but sequential optic neuropathy, often non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) in one eye that proceeds to optic atrophy after initial optic disc edema followed by an acute NAION in the fellow eye. Any bilateral sequential optic neuropathy with optic disc edema however can produce the pseudo FKS (PFKS). The PFKS is due to cases without an intracranial tumor present.

The Pseudo-Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome (PPFKS) is characterized by a combination of ischemic optic neuropathy and papilledema; however, these findings are a result of two separate pathologies rather than one. PPFKS presents concurrently with acute vision loss in one eye (NAION) and vision loss in the other eye from papilledema.[2] Gelwan et al described an 80-year-old woman who presented with NAION in her left eye (OS). The right eye (OD) showed optic atrophy and a superior temporal visual field defect due to compression from a tuberculum sella meningioma extending into the right optic canal and compressing the right optic nerve. Thus, the patient had two diseases, NAION (OS) with optic disc edema in one eye and meningioma causing optic atrophy OD. The authors termed this PPFKS.

Pathogenesis

FKS is caused by an intracranial mass that directly compresses the optic nerve resulting in ipsilateral optic nerve atrophy and chronically elevated intracranial pressure leading to contralateral papilledema.[3]

In PPFKS, an intracranial mass with a concurrent contralateral unrelated NAION is present, “such that one optic nerve is atrophied due to the direct compression” from the intracranial mass while the other nerve becomes swollen due to NAION.[2]

In both FKS and PPFKS, the compressive intracranial mass is most commonly a meningioma. There have however been cases in which the compression is due to a craniopharyngioma, pituitary adenoma, neuroblastoma, frontal lobe abscesses, or even an aneurysm.[3]

Diagnosis

History

- Acute unilateral vision loss secondary to optic nerve atrophy

- Symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (e.g., nausea, vomiting, headache, double vision, transient vision loss etc.)[1]

Physical Examination

- Visual acuity is acutely affected in the ipsilateral eye with ischemic optic neuropathy[2] and variably affected in the contralateral eye

- Visual field loss secondary to optic nerve compression (e.g., scotoma, enlarged blind spot)

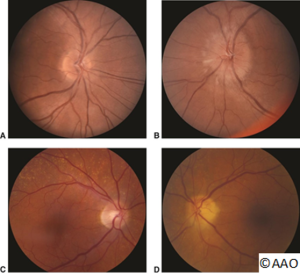

- Fundoscopy reveals optic atrophy and contralateral papilledema

- Diplopia may occur secondary to tumor compression and cranial nerves involvement [1]

Ocular Findings

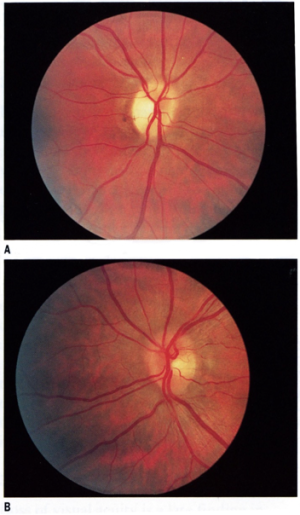

- FKS

- Ipsilateral optic nerve atrophy with contralateral papilledema is the typical presentation of FKS.

- PPFKS

- PPFKS is characterized by compression optic atrophy due to an ipsilateral intracranial mass plus contralateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION).

Diagnostic Procedure

- Comprehensive visual testing

- Full neurological examination [6]

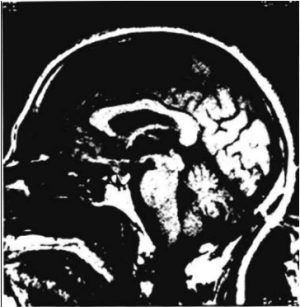

- Neuroimaging studies such as head and orbital CT and/or MRI with and without contrast [1]

- Temporal artery biopsy if Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) suspected (consider in elderly patients) [7]

Pathology

Meningiomas originate from arachnoid cap (meningothelial) cells. They are categorized into 15 subtypes with varying histological appearances. Most meningiomas are benign, showing a lack of invasion.[8]

Laboratory Tests

In all patients older than 50, laboratory testing for giant cell arteritis (GCA) should be obtained which includes a complete blood count, ESR, and CRP tests. These tests may help differentiate between NAION and AAION. Abnormal values can be seen in GCA. The expected findings for these tests have been summarized in the table below.

| ESR | CRP | Platelets | |

| NAION | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| AAION | Elevated | Elevated | Elevated |

Imaging

Radiographic features vary depending on the etiology but generally, an intracranial mass causing optic nerve compression and resulting in features of optic atrophy can be seen.[3]

Exclusionary Criteria

The presence of both compression due to intracranial mass and ischemic optic neuropathy is necessary for diagnosis of PPFKS. Patients with only the former should be considered for FKS. Patients with only the latter should be evaluated for Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome (PFKS), which is a diagnosis of exclusion.[7]

Differential Diagnosis

- FKS[9]

- Frontal lobe parenchymal tumor

- Meningioma (frontal, sphenoid, olfactory, etc.)

- Basal tumor

- Cholesteatoma

- PPFKS[1]

Management

General Treatment

Management for PPFKS depends on the underlying cause:

In all patients older than 50, laboratory testing for giant cell arteritis (GCA) should be obtained which includes a complete blood count, ESR, and CRP tests. If the patient has symptoms suggestive of GCA such as a headache or an abnormal ESR or CRP level, systemic steroids should be started immediately to prevent blindness in the patient.[7] This should be followed by a temporal artery biopsy to confirm GCA. Since GCA can present with skip lesions, it is important to remember that 5% of biopsies can have a false negative due to an inadequate specimen length.

Meningiomas compressing the optic nerve are primarily treated with surgical resection. To further reduce peritumoral edema and intracranial pressure from symptomatic tumors, corticosteroids are also utilized.[1] Patients who prefer a non-surgical approach can be treated using stereotactic radiotherapy or radiosurgery. This also pertains to older patients who are more prone to complications following neurosurgery.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the underlying etiology. On average, patients affected with A-AION are older and have worse visual outcomes in comparison to those with NAION.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Al-Othman, B., Zehden, J., & Igbinoba, R. (2021, November 27). Foster-Kennedy vs pseudo-foster-kennedy. EyeWiki. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://eyewiki.aao.org/Foster-Kennedy_vs_Pseudo-Foster-Kennedy

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Gelwan, M. J., Seidman, M., & Kupersmith, M. J. (1988). Pseudo-Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, 8(1), 49–52.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sharma, R. (2021, March 30). Foster Kennedy syndrome: Radiology reference article. Radiopaedia Blog RSS. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://radiopaedia.org/articles/foster-kennedy-syndrome?lang=us#nav_treatment-and-prognosis

- ↑ Foster Kennedy syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology. (2021, May 26). Retrieved December 29, 2021, from https://www.aao.org/image/foster-kennedy-syndrome

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 ONH appearance in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. American Academy of Ophthalmology. (2017, July 13). Retrieved December 29, 2021, from https://www.aao.org/image/new-mediabeacon-item-62

- ↑ Bindhu, H. (2015, April 3). Foster Kennedy's syndrome. Medindia. Retrieved December 20, 2021, from https://www.medindia.net/medical-syndromes/neurological-conditions/foster-kennedys-syndrome.htm

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Vickers, Laura A., MD, M. Tariq Bhatti, MD, and Mays A. El-Dairi, MD. "Diagnose and Manage Pseudo–Foster Kennedy Syndrome." EyeNet Magazine Jan. 2014.

- ↑ Shibuya M. Pathology and molecular genetics of meningioma: recent advances. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2015;55(1):14-27.

- ↑ Massey, E. W., and B. Schoenberg. "Foster Kennedy Syndrome." Archives of Neurology 41.6 (1984): 658-59.

- ↑ Ap, Vignesh. “Pseudo-Foster Kennedy Syndrome Due to Diabetic Papillopathy.” Advances in Ophthalmology & Visual System, vol. 2, no. 4, Dec. 2015.