Facelifting Techniques

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Overview of Facelifting (Rhytidectomy) Techniques

Disease Entity:

Facelifting, also known as Rhytidectomy, is a procedure that attempts to reverse the natural process of facial aging through surgical manipulation to correct soft tissue (skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle) ptosis.

Disease:

| Surgical Procedure | CPT Code |

| Rhytidectomy | 15828, 15829 |

Background:

The word rhytidectomy stems from Greek origin, with rhytis meaning “wrinkle” and ektome meaning “excision,” to give the word the modern day meaning of wrinkle excision. Facelifting techniques involve a combination of removing excess facial skin, muscle suspension, removal or plication with or without adjunctive techniques such as cervicoplasty, laser or chemical peel resurfacing. While a facelift can be done in combination with blepharoplasty, browpexy, muscle chemodenervation or other cosmetic procedures, facelifts typically address the soft tissue of the mid-face (3).

There are several techniques commonly used to perform a facelift, which will be discussed in later sections, but the differences are mainly focused on the depth of surgical dissection, management of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), and incision placement. Decision of which technique to use is largely determined by surgeon preference/comfort patient expectations and overall severity of facial rhytides.

Historical Perspective:

Facelifts have been reportedly performed as early as the 1900s, with early surgeries done by pulling at the edge of the face and excising excess skin (7). The first major publication describing facelifts came from Dr. Raymond Passot in 1919 (8). Since then, there have been many changes to the technique and thought processes behind facelifts, with the next major change occurring in the 1970s with introduction of SMAS targeted approaches. Greater knowledge of facial anatomy and physiology led to the concept of adjusting the SMAS layer of the face to achieve longer lasting results rather than relying on superficial skin excision to perform the lift (9).

This concept further evolved with the advent of subperiosteal elevation as another approach to rejuvenate the face. Some modern facelifting techniques are centered around a minimally invasive approach to avoid scarring, while still achieving similar outcomes to prior aggressive approaches. With the introduction of smartphone cameras (with these cameras often causing facial distortion) and the predominance of social media in today’s lifestyle, increasing emphasis has been placed on facial appearance. This has caused a spike in interest for facelifts and other facial rejuvenating surgeries. According to the 2020 plastic surgery statistics report, facelift is now the third most common cosmetic surgical procedure behind only rhinoplasty (nose re-shaping) and blepharoplasty (eyelid rejuvenation) (11).

Anatomy:

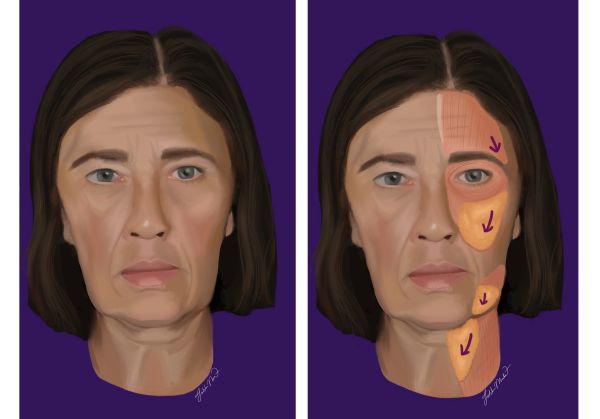

Facelifts focus on the correction of ptotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in the temporal, infraorbital, buccal, zygomatic and parotidomasseteric region of the face. For techniques related to forehead or upper face rejuvenation, see “Endoscopic Brow Lift” as classical facelifting techniques do not focus on this area.

The facial nerve runs through these facial regions, with the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, and mandibular branches at the highest risk of being injured. The blood supply is provided by major branches off the external carotid artery including the facial artery, maxillary artery, and superficial temporal artery.

Pre-operative physical exam findings

A classic patient seeking a facelift will present with a combination of fat loss in the cheeks, prominent nasolabial folds, hollowed out midface and rhytides around the eyes, mouth, chin, and neck.

Facelifting is a cosmetic procedure, so decision for surgery is based on patient preference. Similarly, there is no cutoff for age, but recent rhytidectomy census data shows 64% of patients are aged 55-69, with most identifying as female (11). The largest percentage (30%) of patients undergoing a facelift are from the South-Atlantic region (DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV) and are typically Caucasian.

Perioperative Assessment

Prior to any surgical intervention, a thorough history and physical examination should be obtained. Patients should be asked about their past medical history, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension), past surgical history (prior facelifts, facial surgeries, facial trauma, non-surgical rejuvenation) and smoking status. Patients should also be asked specifically about their medications and supplements, as some herbal supplements increase bleeding risk. Patients should be asked to hold any antiplatelet or blood thinning agents for the appropriate number of days (2 – 14 days) prior to surgery to minimize bleeding risk.

The physical exam starts with examination of the face both at rest and on animation. The face should be evaluated as a whole for the overall shape (round, wide, thin, etc.), as well as for equality of horizontal facial thirds and vertical facial fifths. The forehead, eyelids, cheeks, perioral area and neck should all be examined. One should look at the distribution of facial fat, the structure of the underlying skeleton, skin quality (rhytids, photoaging, depth of folds), ptosis, and soft tissue atrophy. The neck should be examined in neutral, flexion, and in a side view to determine the degree of platysmal laxity, sub -and pre- platysmal fat, ptosis of the submandibular gland, and platysmal bands. The ear should be examined for possible incision placement; this includes examining attachment of the tragus, size of the earlobe, location of hairline, and hair surrounding the ear. One should take accurate and standardized photos for operative planning and comparison of post operative results to pre-operative findings.

Pre-operative counseling

As with most cosmetic procedures, one of the first steps in pre-facelift counseling is to establish patient goals and set realistic expectations for post-surgery appearance. Depending on a patient’s baseline facial structure and preferred outcome, the surgical team can determine the optimal surgical approach. One must consider the quality of the skin, the depth and location of folds, and the weight of the soft tissue. Old photographs may be helpful to facilitate a discussion regarding what the patient would most like to improve.

While there is typically low risk of complication, poor outcomes do occur; these include hematomas, skin necrosis, under or over correction, wound breakdown, poor healing, seroma or infection. It is important to discuss these possibilities prior to surgery. Hematoma is the most common complication in facelift surgery. Smokers have an increased risk of skin flap necrosis and elective facelifts; surgeons may elect to avoid surgery in smokers unless it has been confirmed that they have stopped smoking for several weeks prior to surgery.

A pre-auricular incision is the typical approach for most facelift techniques. If extra skin must be excised, the incision can get extended superiorly into the temporal hairline or the incision may be extended post-auricularly to camouflage the incision behind the ear.

Types

Subcutaneous Facelift

The subcutaneous facelift is one of the earliest facelift techniques. The surgery involves simple skin excision with approximation of new skin edges to rearrange skin patterns in a way that reverses patterns of aging. The classic initial incision runs from the temporal forehead, directly at the beginning of the hairline, inferior to the mandibular angle. There is a degree of variability with regards to posterior auricular incisions, as this factor depends upon patient anatomy and baseline skin creases. Subcutaneous facelifts are still occasionally used due to their fast recovery, easy to learn technique, and low risk profile. The disadvantage to this technique is that it depends on skin tension to provide the facelift, with large scars being possible as the patient ages (3). Results are not as long lasting; risk of recurrence is high.

Superficial Musculo-Aponeurotic System (SMAS) Facelift

Developed by Tord Skoog in the 1970s, the SMAS plication facelift is the first surgical facelifting technique that delved into the deeper fascial planes. The SMAS lies beneath the subcutaneous tissue and directly above the parotidomasseteric fascia (12). The SMAS extends superiorly to the zygomatic arch and temporoparietal fascia and extends inferiorly to the platysma muscle. The operation itself consists of creating an incision at the temporal region, superior and anterior to the ear, that will continue through the preauricular area before extending posterior to the post-auricular sulcus. Once this excision has been made, a flap will be present and the SMAS can be identified by simple dissection.

By plicating and removing sections of the SMAS, soft tissues of the face become resuspended, allowing the skin and soft tissue laxity in the face to be reversed. Since this method is more invasive than the subcutaneous facelift, higher rates of facial nerve damage and wider ranges of patient long-term satisfaction have been reported. However, this method has relatively low complication rates and is generally considered safe and easy to perform. There are several modern-day variations of this technique, including combining SMAS with subcutaneous facelift for a multi-targeted approach.

Deep Plane Facelift

A popular variation of the SMAS technique, this approach is utilized for patients requiring more intense nasolabial fold reconstruction. Some surgeons believe that this technique results in more stable and long-lasting results. Deep plane facelift focuses on the levels deeper than the SMAS, with rearrangement of fat, ligaments, and muscles originally attached to bone. The benefits of this surgical technique include more focused nasolabial reconstruction, potential for longer lasting facelift, and less strain on superficial facial tissue leading to more natural appearing results. Similarly to the SMAS technique, deep plane facelifting runs significant risk of facial nerve injury due to the depth of surgical dissection. (13)

Composite Facelift

The composite facelifting technique accomplishes facial rejuvenation by targeting all aspects of the midface. The composite facelift is surgically like the deep plane facelift, but transfers facial tissue in a superomedial pattern, as compared to the superolateral movement of other facelifting techniques. This approach addresses the “hollow eye” appearance that accompany other techniques.

Arcus marginalis release and septal reset help fill in the space underneath the eye causing a natural looking lift (14). The advantages to the composite surgical facelift include better lower lid appearance and more natural looking facelift. Disadvantages include prolonged recovery time, along with requiring higher skill and training level to perform.

Deep Subcutaneous Facelift

This technique targets the deeper subcutaneous tissue of the face, directly above the SMAS. Developed to avoid damaging the facial nerve, this method utilizes a similar surgical technique to normal subcutaneous facelifting but with deeper dissection. The advantages of this method are that the flap being made is thicker than with the original subcutaneous facelift, and as compared to SMAS, there is a lower risk of complications. Disadvantages include that, similar to other subcutaneous methods, deep subcutaneous facelift results rely on skin tightening only to maintain tension on the lift with skin following the deep subcutaneous tissue in a linear pattern.

Minimal Access Cranial Suspension (MACS)/Mini Facelift (S-Lift)

MACS/Mini facelift technique is a more modern approach to the facelift that uses a small “S” shaped incision (hence the surgery is also referred to as “S-Lift”) and an endoscope to cause minimal post-operative scarring. Intended to provide more short-term benefit, this facelift begins with an excision in similar position to previously discussed facelifts at the temporal hairline. Since the incision is smaller than with other facial surgeries, the goal is to excise within a natural wrinkle to prevent visible scarring.

Using an endoscope, the soft tissues of the face are repositioned with small sutures. Advantages to this surgery include fast recovery times and high aesthetic appeal (16). Disadvantages include high surgical complexity, limited data showing usefulness and limitations, and need for endoscope. This surgical technique is limited in use by the lack of access to the neck, so for more intensive rejuvenation, a mini facelift is largely impractical. (15)

Subperiosteal Facelift

Originally developed in the late 1970s, this approach uses classic incision locations but with a deeper level of dissection (3). This technique gained prominence with the introduction of the endoscope, as a subperiosteal facelift consists of completely separating the soft tissue layers of the face from underlying facial bones. By operating below the layer of the facial nerve, there is a reduced incidence of nerve damage with this type of facelift. When used in combination with other, more superficial techniques, long-term patient satisfaction is high. Disadvantages to the subperiosteal approach are need for an endoscope and a high degree of post-operative facial swelling.

Post-operative care

Facelifts can be done either as an inpatient or outpatient procedure based on patient and surgeon preference. After surgery, the surgically operated facial tissue will be dressed for skin protection and compression (in the form of a jaw bra), which is employed to minimize swelling and reduce the risk of a hematoma occurrence. In addition, it is common for surgical drains to be placed temporarily until the first follow-up appointment. Peri-operative and post-operative hypertension and pain control are crucial to minimize the risk of hematoma as elevated blood pressures can lead to hematoma requiring urgent surgical takeback and drainage.

Non-absorbable stitches can stay in for as long as two weeks while waiting for the tissue to heal. As expected with most invasive procedures, patients often complain of post-operative pain or discomfort. It is recommended to prescribe short term pain medication based on severity of pain, with options including a short course of opioids or NSAIDs.

Significant bruising and swelling are likely to be present after surgery and can be managed with cool compresses. This swelling and bruising should resolve on its own but can last several weeks. Activity is limited for the first two-three days post-op with return to light activity at this point and return to full activity typically around two weeks post-surgery.

Complications

The most reported complication from facelift surgery is hematoma, with varying rates depending on age, sex, and demographic ranging from 1.3%-6.7% (2). Other complications include dissatisfaction (2.8%), scarring (2.3%), skin flap necrosis (1.9%), asymmetry (1.2%), abnormal skin contour (0.9%), altered expression (0.3%), and nerve injury. The most common motor nerve injuries are to the temporal, marginal mandibular, and buccal nerves with the vast majority of injuries resolving within one year (approximately 0.1% permanent). The most common sensory nerve injury was to the great auricular nerve branch off the cervical plexus (1.6%). The nerve is at greater risk of damage when dissecting in the region of the lateral neck over the sternocleidomastoid.

Prognosis

With the advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques, facelifts are now able to achieve more natural looking facial rejuvenation with faster recovery times. Newer, modern facelifting techniques aim to minimize scarring with smaller incisions concealed at the hairline. While there will be scarring post-operatively, scarring will slowly heal over the course of a year. A long-term complication related to scarring is temporal hair loss or hairline distortion, but this outcome is rare (17).

Facelifts are not a permanent fix to facial aging, with additional surgery sometimes required for further rejuvenation. The length of time that a patient can expect continued rejuvenated facial structure depends on the technique used. Mini facelifts have fast recovery times, but do not have as long-lasting results with relapse in facial sagging sometimes seen as early as 2-3 years post-op. Full facial lifts provide long-term facial reconstruction with studies showing younger appearing facial structure at 5.5 years and beyond (18).

References

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. “American Society of Plastic Surgeons Unveils Covid-19's Impact and Pent-up Patient Demand Fueling the Industry's Current Post-Pandemic Boom.” American Society of Plastic Surgeons, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 27 Apr. 2021,

- Matarasso, Alan M.D.; Elkwood, Andrew M.D., M.B.A.; Rankin, Marlene R.N., Ph.D.; Elkowitz, Marc M.D.. National Plastic Surgery Survey: Face Lift Techniques and Complications. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: October 2000 - Volume 106 - Issue 5 - p 1185-1195

- Warren, Richard J. F.R.C.S.C.; Aston, Sherrell J. F.A.C.S.; Mendelson, Bryan C. F.R.C.S.E., F.R.A.C.S., F.A.C.S.. Face Lift. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2011 - Volume 128 - Issue 6 - p 747e-764edoi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318230c939

- Gassner HG, Rafii A, Young A, Murakami C, Moe KS, Larrabee WF Jr. Surgical anatomy of the face: implications for modern face-lift techniques. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008 Jan-Feb;10(1):9-19. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2007.16. PMID: 18209117.

- “Rhytidectomy.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 July 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhytidectomy.

- “Midface Rejuvenation.” American Academy of Ophthalmology, 9 Nov. 2017, https://www.aao.org/image/midface-rejuvenation.

- Panfilov, Dimitrije E. (2005). Cosmetic Surgery Today. Trans. Grahame Larkin. New York, N.Y.: Thiene. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-58890-334-1.

- Keith A. Denkler, MD, Rosalind F. Hudson, MD, The 19th Century Origins of Facial Cosmetic Surgery and John H. Woodbury, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 35, Issue 7, September/October 2015, Pages 878–889, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjv051

- Skoog, Tord Gustav (1974). Plastic Surgery: New Methods and Refinements. Saunders. p. 500. ISBN 978-0721683553.

- American Society of Plastic Surgeons. “American Society of Plastic Surgeons Unveils Covid-19's Impact and Pent-up Patient Demand Fueling the Industry's Current Post-Pandemic Boom.” American Society of Plastic Surgeons, American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 27 Apr. 2021.

- 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/ News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf

- Joshi K, Hohman MH, Seiger E. SMAS Plication Facelift. [Updated 2022 May 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-.

- “What Is a Deep Plane Facelift? + More Innovations to Take Your Facelift Results to the next Level.” American Board of Facial Cosmetic Surgery, 2 June 2021, https://www.ambrdfcs.org/blog/what-is-a-deep-plane-facelift/.

- Choucair RJ, Hamra ST. Nuances of the Composite Face-lift Technique. Semin Plast Surg. 2009 Nov;23(4):247-56. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242183. PMID: 21037860; PMCID: PMC2884913.

- Hopping SB, Janjanin S, Tanna N, Joshi AS. The S-Plus lift: a short-scar, long-flap rhytidectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010 Oct;92(7):577-82. doi: 10.1308/003588410X12699663904439. Epub 2010 Jun 29. PMID: 20594404; PMCID: PMC3229348.

- Mast BA. Advantages and limitations of the MACS lift for facial rejuvenation. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(6):S139-43. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000092. PMID: 24691336.

- Kridel RW, Liu ES. Techniques for creating inconspicuous face-lift scars: avoiding visible incisions and loss of temporal hair. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003 Jul-Aug;5(4):325-33. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.5.4.325. PMID: 12873871.

- Jones BM, Lo SJ. How long does a face lift last? Objective and subjective measurements over a 5-year period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Dec;130(6):1317-1327. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826d9f7f. PMID: 23190814.

- Mendelson, Bryan C., Wong Chin-Ho. “Anatomy of the aging face.” Aesthetic Surgery of the Face. (2012).