Capillary Hemangioma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Capillary hemangioma (infantile hemangioma, juvenile hemangioma, or strawberry nevus of infancy) is one of the most common benign orbital tumors of childhood affecting up to 5% of infants under the age of 1 year. It can be superficial, presenting as a red, raised lesion, it can be deep, presenting as a dark blue lesion that may extend into the orbit or may present both of the above components. Capillary hemangiomas involving the eyelids may induce astigmatic anisometropic amblyopia causing severe vision loss if left untreated. The diagnosis is made clinically, however in extensive cases imaging helps delineate the extent of orbital involvement. The natural course of the capillary hemangioma is initial enlargement in the first year of life followed by spontaneous regression in the following years. Therefore, treatment is only initiated for lesions threatening vision (from amblyopia, exposure keratopathy, optic neuropathy). The current first-line treatment is beta-blockers, systemically and topically. Other choices of therapy include corticosteroids, both oral and injected, surgical excision, and embolization. Rarely, capillary hemangiomas might be associated with systemic hemangiomas or with other conditions such as PHACES syndrome.

Disease Entity

Demographics

Capillary hemangioma is the most common benign periorbital tumor of childhood. It is present in up to 5% of all births. There is a 3:1 ratio of females to males. The incidence of orbit and eyelid hemangiomas is 1/10 that of systemic hemangiomas, which occurs in 10% of all children by 1 year of age [1].

Anatomical locations

A capillary hemangioma is classified according to its location. It is most commonly found on the eyelid or brow, with a predilection for the upper eyelid. The involvement can be cutaneous, subcutaneous, or with orbital extension.

Pathology

Capillary hemangiomas are classified as hamartomas, or abnormal proliferation of normal tissue in a normal location, namely endothelial cells. Histologically, the appearance of these lesions depends on the stage of the evolution. Early lesions may be very cellular, with solid nests of plump endothelial cells and little vascular lumen. Established lesions comprise of well-developed, flattened, endothelium-lined capillary channels of varying sizes in a lobular configuration. Involuting lesions show increased fibrosis and hyalinization of capillary walls with luminal occlusion [2].

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms

Presentation of capillary hemangiomas usually occurs after birth, but within the first 6 months of life (30% present at birth, 50% by 1-2 months, and 90% by 6 months). Clinically, the hemangioma may present as a cutaneous, subcutaneous, or orbital lesion. In cutaneous lesions, the mass is raised, nodular, and bright red (Figure 1). A subcutaneous lesion may appear dark blue or purple. A lesion extending into the orbit may cause proptosis without overlying skin findings. Often, a capillary hemangioma may enlarge and/or change color with crying; and a cutaneous lesion may blanch with pressure and may have a spongy consistency on palpation. However, capillary hemangiomas are without pulsation and have no bruit [3].

Upper eyelid capillary hemangiomas can cause mechanical ptosis. This can lead to reduced visual acuity due to amblyopia from induced astigmatic anisometropia, strabismus, or rarely occlusion by the eyelid itself.

Astigmatic anisometropic amblyopia is the most common cause of visual impairment and results from direct pressure on the cornea, and in turn, astigmatism, by the thickened eyelid. Deprivational amblyopia occurs when the growing capillary hemangioma occludes the visual axis. Strabismus can occur if the orbital hemangioma exerts mass effect on the globe causing displacement or involves the extraocular muscles.

Imaging

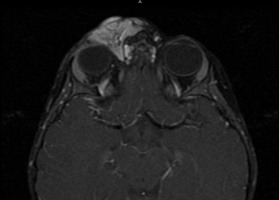

Although the diagnosis is clinical in cutaneous lesions, ultrasound should be used to image the extent of periorbital involvement. If deeper orbital extension is suspected, then CT or MRI may be used. On ultrasound, a capillary hemangioma shows high internal reflectivity with irregular acoustic structures. On CT, the lesion shows a low flow prominence with no disturbance of surrounding tissue and no bony erosion; it enhances with contrast. On Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies, capillary hemangiomas may appear as well-circumscribed densely lobulated tumors. On T1-weighted MRI, the capillary hemangioma is of intermediate signal intensity, but it is moderately hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging (Figure 2) due to the slow blood flow through the vascular channels. The tumor mass may enhance following gadolinium contrast injection, so images should have fat suppression on T1 weighted images to better visualize the tumor. Angiography is rarely used as a diagnostic tool for capillary hemangiomas.

Differential Diagnosis

- Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) of Sturge-Weber syndrome

- Lymphangioma or other vascular malformations

- Metastatic neuroblastoma

Management

The typical course of capillary hemangiomas is characterized by initial enlargement followed by spontaneous regression. 40% of lesions completely involute by age 4, and 80% by age 8 [4].

Hence, the management of capillary hemangiomas depends on the location and whether the lesion causes visual impairment. Indications for treatment include risk of amblyopia, optic nerve compression, exposure keratopathy, severe cosmetic defect, infection and necrosis.

Medical

The first-line of treatment for periorbital hemangiomas that may affect the visual development consists of β-blockers. The most commonly administered agent is oral Propranolol which demonstrated remarkable regression in patients with eyelid capillary hemangiomas with induced amblyopia, up to as old as 5 years of age [5] [6] [7].

Topical administration may be indicated in small superficial lesions or in PHACES syndrome due to high risk of cerebral ischemia with systemic administration [8]. Other possible ways of administration can be intralesional or intravenous. In a recent review of 16 studies using oral and topical propranolol, there was limited evidence (in level II and level III studies and case reports) that either of these were effective at promoting the regression of capillary hemangiomas. [9]

The mechanism of action is not completely understood, it includes vasoconstriction, decreased expression of bFGF and VEGF which are present during the growth phase of the capillary hemangioma [10], as well as the triggering of apoptosis [11]. Cardiac and pulmonary evaluation is essential in all patients before starting treatment and careful monitoring for potential adverse events is needed: bradycardia, bronchospasm, hypotension, and hypoglycemia. [12]. Propranolol use in patients with PHACES syndrome could be challenging since there is an increased risk for an acute ischemic stroke especially for those with severe, long-segment narrowing of major cerebral or cervical arteries, absence of adequate collateral circulation and co-existing aortic arch and cardiac abnormalities[12].In these cases, extended imaging with magnetic resonance imaging(MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography(MRA) of the head and neck as well as a cardiology consultation is warranted before initiation of propranolol.

Corticosteroids may also be used in the treatment of capillary hemangiomas. Systemic, intralesional injection, and topical steroids have been used with varying degrees of success. Systemic therapy showed some benefit in diffuse or orbital lesions [13]. But rebound growth after discontinuation, and significant side effects such as increased risk for growth delay, immunosuppression, behavioral disturbances, adrenal insufficiency made the therapy suboptimal. Intralesional steroid injection was the preferred first-line treatment. It has proven efficacious in diminishing the size of the lesion rapidly within two weeks of injection in many cases [14]. However, intralesional steroid injections carry significant risks and complications, including CRAO from embolization of the steroid material, skin necrosis, skin hypopigmentation and fat atrophy. Topical steroid application has also been suggested. Although with fewer side effects, its efficacy was limited and was recommended only as adjunctive therapy for superficial lesions.

Immunomodulators such as cyclcophosphamide and interferon alpha-2a and 2b have also been tried systemically. However, the treatment course takes several months, leading to significant adverse effects such as bone marrow suppression and hepatotoxicity [15].

Surgical

Laser photocoagulation has been used to stimulate regression of cutaneous hemangiomas. Carbon dioxide, argon, neodymium-YAG, and flash-lamp pumped-dye laser have all been utilized in the treatment of capillary hemangiomas. Laser treatments have been found to be more effective for early and superficial lesions and less effective in deeper orbital lesions.. It is currently recommended as adjunctive therapy for very superficial lesions.

Radiation therapy can be effective in the management of certain capillary hemangiomas. Microembolisms can be created in the tumors by low-level radiation, which can speed the regression of the mass.

Embolization by interventional radiology has reported good outcomes as an alternative or adjunct to resection[16].

Surgical excision remains an option, usually reserved for cases where conservative therapy has failed or was suboptimal, and tumor removal is necessary[17]. The highly vascular tumor may create a significant higher risk of intraoperative bleeding. Surgery can reduce tumor size by compromising the tumor feeder vessels, constriction and sclerosing of the small vascular channels, or primary excision of the entire mass can be performed.. However, complete excision is difficult as the hemangiomas tend to be unencapsulated.

In addition to treating the hemangioma, it is important to manage the patient’s visual rehabilitation with optimal refraction and occlusive therapy concurrently.

Associations

- Kasabach-Merrit syndrome characterized by thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia and coagulopathy and is associated with large visceral hemangioma. The thrombocytopenia occurs because of platelet sequestration within the tumor's vascular channels. Although rare, this is a condition with high mortality which requires prompt management by multiple subspecialists.

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) was also described with periocular, gastrointestinal and liver hemangiomas. In MAHA erythrocytes are destroyed from coagulation, or are sheared or fragmented by high pressure forcing them through the abnormally small vessels of the hemangioma.

- PHACES syndrome (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects, Eye abnormalities, Sternal cleft and supraumbilical raphe syndrome) is suspected especially if the hemangioma involves more than one dermatome. It is associated with an increased risk of amblyopia and more likely to require treatment.

- Periocular capillary hemangiomas may also occur simultaneously with oral, nasal, subglottic, and paratracheal hemangiomas.

- Maffucci syndrome is characterized by multiple cutaneous and visceral hemangiomas along with the presence of multiple enchondromas. [18].

Additional Resources

- Turbert D, Lipsky SN. Hemangioma. American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/hemangioma-list. Accessed March 13, 2019.

References

- ↑ Frieden, I. J. et al. Pediatr Dermatol 2005;22:383–406.

- ↑ “Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors.” Basic and Clinical Science Course. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2010-2011.

- ↑ “Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.” Basic and Clinical Science Course. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2010-2011.

- ↑ Drolet, B.A. et al. “Hemangiomas in Children.” N Eng J Med 1999;341:173-181.

- ↑ Vassallo, P. et al. “Treatment of Infantile Capillary Hemangioma of the Eyelid with Systemic Propranolol.” Am J Ophth. 2012 Sep 8.

- ↑ Thooumazet F. et al. “Efficacy of Systemic Propranolol for Severe Infantile Haemangioma of the Orbit and Eyelid: A Case Study of Eight Patients.” Br J Ophth. 2012;96(3):370-4.

- ↑ Missoi, T.G. et al. “Oral Propranolol for Treatment of Periocular Infantile Hemangiomas.” Arch Ophth. 2001;129(7):899-903.

- ↑ Chambers, C.B. et al. “A Controlled Study of Topical 0.25% Timolol Maleate Gel for the Treatment of Cutaneous Infantile Capillary Hemangiomas.” Ophth Plast Recon Surg. 2012;28(2):103-6.

- ↑ Hutchinson AK, Kraker RT, Pineles SL, VanderVeen DK, Wilson LB, Galvin JA, Lambert SR. The use of B-Blockers for the treatment of periocular capillary hemangiomas in infants: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2019 Jan;126(1):146-155.

- ↑ D’Angelo, G. et al. “cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits the mitogenic action of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor in capillary endothelial cells by blocking Raf activation.” J Cell Biochem 1997;67:353-66.

- ↑ Sommers Smith, S.K. et al. “Beta blockade induces apoptosis in cultured capillary endothelial cells.” In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2002;38:298-304.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Drolet BA et al."Initiation and Use of Propranolol for infantile Hemangioma: Report of a consensus Conference". Pediatrics 2013;131(1):128-140

- ↑ Schwartz, S. et al. J AAPOS 2007;11:577–583.

- ↑ Coats, D. K. et al. “SubTenon’s infusion of steroids for treatment of orbital hemangiomas.” Ophthalmology 2003;110:1255–1259.

- ↑ Wilson, M.W. et al. “Low-dose cyclophosphamide and interferon alfa 2a for the treatment of capillary hemangioma of the orbit.” Ophthalmology 2007;114:1007–1011.

- ↑ Ooi KG, Wenderoth JD, Francis IC, Wilcsek GA. "Selective embolization and resection of a large non involuting congenital hemangioma of the lower eyelid". Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Mar-Apr;25(2):111-114

- ↑ Men CJ, Ediriwickrema LS, Paik JS, Murdock J, Yen MT, Ng JD, Liu CY, Korn BS, Kikkawa DO. Surgical Intervention of Periocular Infantile Hemangiomas in the Era of β-Blockers. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020 Jan/Feb;36(1):70-73. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001466. PMID: 31809485.

- ↑ Hall, G. "Kasabach–Merritt syndrome: pathogenesis and management". Br J Haematol 2001;112(4):851–62.