PHACES Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

PHACES syndrome, an associated collection of disorders, is also sometimes called PHACE association, PHACE syndrome, Pascual-Castroviejo type II syndrome (P-CIIS), or sternal malformation-vascular dysplasia association. [1] [2] ICD-10: Q28.8

Disease

PHACES is an acronym denoting major features of the disorder: Posterior fossa malformations (such as Dandy-Walker cysts), hemangioma of the cervicofacial region, arterial anomalies (usually head or neck), cardiac anomalies (such as Coarctation of the aorta), ocular anomalies, and sternal or abdominal clefting or ectopia cordis. [3]

PHACES syndrome (PS) is a rare neurocutaneous disorder with cardiac, dermatological, neurological, and ocular manifestations. The hallmark of PS is a massive hemangioma usually in the face, neck, or scalp region. A study found that up to two-thirds of children with PHACES have infantile facial hemangiomas that can cause vision-threatening amblyopia and strabismus. [4]The most frequently found extracutaneous manifestations include cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and structural neurological abnormalities. The majority of the patients, up to 70%, have only one extracutaneous manifestation. Additionally, up to one-third of patients have been found to have periocular and ocular manifestations. [3] These ocular manifestations include microphthalmos, exophthalmos, congenital glaucoma, Horner’s syndrome, strabismus, colobomas, corneal opacity, cataracts, conjunctival or choroidal hemangiomas, retinal hypervascularity or dysgenesis, optic disc edema, optic atrophy, and optic nerve hypoplasia. [3] [5]

Etiology

PHACES syndrome is a relatively rare disorder with an unknown etiology. It is considered a non-hereditary condition with most cases being sporadic. Some studies show a possible X-linked correlation with PHACES syndrome which accounts for the female predominance and high male prenatal mortality. Additionally, there are multiple genetic and phenotypic anomalies, and some authors have suggested a developmental error most likely occurring between 3 and 12 weeks of gestation. [1] [7]

Epidemiology

PHACES syndrome is found in about 2% to 3% of all infantile hemangioma cases worldwide. There is a female predominance with a 9:1 female to male ratio. PS is more common among Caucasian and Hispanic populations. The risk of developing an extracutaneous abnormality increases with the size of the hemangioma and with the extent the hemangioma covers the face. Some studies suggest the likelihood of the PS to be as much as 20% to 31% in patients found to have large or segmental facial hemangioma. [7]

Risk Factors

There are no known risk factors for PHACES syndrome. However, one study by Wan et al. found significantly higher rates of pre-eclampsia and placental abnormalities, especially placenta previa among PHACES syndrome patients. The study concluded these to be the risk factors specifically for the hemangioma element of the PHACES syndrome. Hypoxia is another major risk factor for the hemangioma development and hence may be a contributor to PHACES syndrome. [8]

General Pathology

Every patient diagnosed with PS has a different combination of symptoms and usually presents with an extensive or segmental infantile hemangioma associated with brain, cardiac, aortic, arterial, or ocular abnormalities. [7]

PHACES acronym describes the group of anomalies associated with the disorder:

- Posterior fossa malformations: congenital brain malformations, more frequently of the back, for example Dandy-Walker cysts.

- Infantile Hemangioma: a benign vascular lesion involving the face, neck, or scalp region.

- Arterial anomalies usually of the head or neck.

- Cardiac defects: congenital heart or aortic abnormalities such as coarctation of the aorta.

- Eye abnormalities.

- Sternal or ventral defects.

Pathophysiology

Currently, the pathophysiology behind developing PHACES syndrome is still unknown. This disease process does not have any familial inheritance patterns and is a separate disease entity from isolated hemangiomas. One of the leading theories is that children with PHACES syndrome undergo a developmental defect during embryogenesis between weeks 3 and 12 of gestation. At this time, there is no evidence of any specific genetic abnormalities associated with PS. [7]

Some authors have suggested a possible somatic mutation in the cells of neural crest origin which are responsible for the proper structural development of the brain, heart, and the trunk via cell migration during embryogenesis. This could possibly explain the midline defects of the brain and sternum and the anomalies of the cerebral and cervical arteries. [9] [10]

Additionally, due to the female predominance and a more severe disease associated with males, some authors hypothesize a mutation in the X- linked genes. However, a comparative study has failed to find more severe phenotype among male patients when compared to females. [11] An analysis of a genome-wide copy number variation by a study of 98 PHACES syndrome patients revealed no common duplication or deletion. [12] Thus, it is possible the etiology of PHACES syndrome is multifactorial: a complex pathogenetic process with multiple mutations and gene-environment interactions such as fetal hypoxia and vascular abnormalities. The abnormal vasculogenesis and the disruption of the arterial walls can then lead to the formation of the hemangiomas and other abnormalities in the brain. [1]

Primary prevention

Since the etiology or pathophysiology is still not fully known, there are no existing recommendations for the primary prevention of PHACES syndrome.

Diagnosis

A systemic evaluation is required, and PHACES syndrome is suspected if the cervicofacial hemangioma is greater than 5 cm in size in an infant. [1] Therefore, thorough history taking and physical examination are imperative. An ophthalmologic exam is also necessary to detect any ocular abnormalities associated with PHACES syndrome (refer to Physical Examination section).

In 2009, a group of different specialties (neurology, dermatology, genetics, oncology, ophthalmology, and cardiology) established the diagnostic criteria with an update in 2016 of a definite PHACES syndrome and a possible PHACES syndrome. Definite PHACES syndrome is defined as having a craniofacial hemangioma of more than 5 cm in size associated with at least one major criterion or two minor criteria. Possible PHACES syndrome requires the detection of a craniofacial hemangioma of more than 5 cm in size and one minor criterion. [13]

Chart 1: Major and Minor criteria for PHACES syndrome [13]

| System | Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Vascular/Arterial |

|

|

| Structural brain |

|

|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| Ophthalmic |

|

|

| Sternal or Ventral |

|

|

History

The first description of a patient with characteristics of PHACES syndrome (a large facial hemangioma and cervicocranial arterial abnormalities) was reported by Pascual-Castroviejo in 1978. [14] The acronym PHACE was created by Frieden et al. in 1996, and it was Boulinguez et al. who further expanded the acronym to PHACES in 1998. [15] [16]

Physical examination

As a neurocutaneous disorder, PHACES syndrome is characterized by a sizable segmental cervicofacial hemangioma which can be absent, mild, or apparent after birth. The hemangioma can appear either as a red macule with markable telangiectasia, an erythematous patch, a red-bluish soft mass, or clustered papules. The lesion can be unilateral or bilateral and commonly occurs in a dermatomal fashion covering the CN V (V1, V2 or V3) territory. Lesions initially proliferate and slowly shrink leading to full regression. [1]

Although it is not clear, some studies report frontotemporal and frontonasal hemangiomas to be at higher risk of being associated with brain, ophthalmic, and cerebrovascular manifestations. On the other hand, mandibular hemangiomas are more likely to possess midline and cardiovascular involvement. [7]

The non-cutaneous findings as described previously involves the heart, aorta, brain, cerebral vessels, chest wall, and the eyes. The most common of these findings are cerebrovascular (91%), cardiovascular (67%), and structural brain (52%) abnormalities. [1]

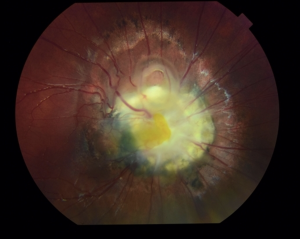

The ophthalmologic exam can reveal strabismus, amblyopia, and anterior and posterior segment anomalies. Anterior segment anomalies may include colobomas, iris hypoplasia, corneal opacity, and cataracts. Posterior segment anomalies include persistence of fetal vasculature, morning glory disc anomaly (Fig.1), optic nerve atrophy or hypoplasia, optic disc edema, and peripapillary staphyloma. Retinal hypervascularity and dysgenesis are other ocular findings in these patients. [3] [5] [17]

Signs and Symptoms

The patients with PS have signs and symptoms corresponding to the acronym PHACES.

- Posterior fossa malformations: microcephaly, congenital brain malformations, more frequently of the back, for example Dandy-Walker cysts

- Infantile Hemangioma: a benign vascular lesion involving the face, neck, or scalp region

- Arterial anomalies usually of the head or neck

- Cardiac defects: congenital heart or aortic abnormalities such as coarctation of the aorta

- Eye abnormalities: microphthalmos, exophthalmos, congenital glaucoma, Horner’s syndrome, strabismus, colobomas, corneal opacity, cataracts, conjunctival or choroidal hemangiomas, retinal hyper-vascularity or dysgenesis, optic disc edema, optic atrophy, and optic nerve hypoplasia

- Sternal or ventral defects

- Endocrine abnormalities due to hypopituitarism

- Ectopic thyroid

- Omphalocele

- Micrognathia

- Auricular hypoplasia

- Ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss

- Orofacial clefting

- Esophageal diverticulum

Diagnostic procedures

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head, neck, and aortic arch with and without contrast

- Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the head, neck, and aortic arch

- Ophthalmologic examination including slit lamp examination and indirect ophthalmoscopy

- Echocardiogram

- Antenatal ultrasound and MRI to detect abnormalities of the posterior fossa in the prenatal period

- Endocrinological workup

- Hearing screening

- Speech and swallow evaluation

- Neuro-developmental screening

Differential diagnosis

- Isolated infantile hemangioma

- Port-wine stain

- Visceral hemangioma

- Sturge-Weber syndrome

- Wyburn-Mason syndrome

- LUMBAR syndrome (Lower body hemangioma, Urogenital anomalies and Ulceration, Myelopathy, Bony deformities, Anorectal malformations and Arterial anomalies, Renal anomalies)

Management

The management of PHACES syndrome is multidisciplinary with no standard protocol for an affected individual. The treatment is targeted around the extracutaneous manifestations and is directed towards the specific findings in the patient. An interdisciplinary approach involving neurologists, cardiologists, and ophthalmologists is usually necessary.

When systemic treatment is indicated, propranolol is the first-line therapy for the infantile hemangioma. However, due to its beta blocker properties, caution should be used because of the risk of stroke in these patients (due to abnormal vasculature). [18] Topical beta blockers may also be a treatment option for superficial hemangiomas, however systemic absorption has been shown by some studies, specifically of topical timolol. [19] Corticosteroids used to be the initial management of the hemangiomas, but they are no longer in widespread use due to their increased side effects as well as risk for acute stroke. Surgery or laser therapy can also be used for resistant hemangiomas. [1]

Aspirin is usually recommended as prophylaxis to prevent any ischemic events. [1] Patients with PS usually require ongoing surveillance, screening, and clinical and imaging follow-up.

Complications

Bleeding, ulceration, and advancement of hemangioma are possible and can eventually lead to impaired vision or vision loss. The most common cardiovascular complication is coarctation of the aorta which can lead to high blood pressure and headaches. There are multiple ophthalmological complications like glaucoma, cataract, or strabismus. These patients are also at risk of developing migraines, seizures, ischemic strokes, and developmental or speech delays. Endocrine abnormalities due to hypopituitarism and hypothyroidism may arise as well. [1] [13]

Prognosis

The prognosis is variable since it depends on the involved extracutaneous manifestations. Not much is known about the life span or long-term outcomes in these patients. Neurological and cognitive impairment are significant roots of morbidity in these patients.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Chamli A, Litaiem N. PHACE Syndrome. [Updated 2020 Jun 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.med.ucf.edu/books/NBK539722/

- ↑ Hersh, J. H., Waterfill, D., Rutledge, J., Harrod, M. J., O'Sheal, S. F., Verdi, G., Martinez, S., & Weisskopf, B. (1985). Sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association. American journal of medical genetics, 21(1), 177–202. https://doi-org.ezproxy.med.ucf.edu/10.1002/ajmg.1320210127

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Kronenberg, A., Blei, F., Ceisler, E., Steele, M., Furlan, L., & Kodsi, S. (2005). Ocular and systemic manifestations of PHACES (Posterior fossa malformations, Hemangiomas, Arterial anomalies, Cardiac defects and coarctation of the Aorta, Eye abnormalities, and Sternal abnormalities or ventral developmental defects) syndrome. Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 9(2), 169-173.

- ↑ Soliman SE, Wan MJ, Pennal A, Pope E, Mireskandari K. Ophthalmic involvement in PHACES syndrome: prevalence, spectrum of anomalies, and outcomes. J AAPOS. 2022 May 10:S1091-8531(22)00095-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2022.01.011. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35550864.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 Coats, D. K., Paysse, E. A., & Levy, M. L. (1999). PHACE: a neurocutaneous syndrome with important ophthalmologic implications: case report and literature review. Ophthalmology, 106(9), 1739-1741.

- ↑ Yonekawa, Y. “Morning Glory Disc Anomaly.” Retina Image Bank, 2020, https://imagebank.asrs.org/file/66348/morning-glory-disc-anomaly.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Rotter, A., Samorano, L. P., Rivitti-Machado, M. C., Oliveira, Z. N. P., & Gontijo, B. (2018). PHACE syndrome: clinical manifestations, diagnostic criteria, and management. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia, 93(3), 405-411.

- ↑ Wan, J., Steiner, J., Baselga, E., Blei, F., Cordisco, M., Garzon, M. C., Goddard, D. S., Haggstrom, A., Krol, A., Frieden, I. J., Metry, D., Morel, K. D., Verhagen, J., Wargon, O., Drolet, B. A., & Siegel, D. H. (2017). Prenatal Risk Factors for PHACE Syndrome: A Study Using the PHACE Syndrome International Clinical Registry and Genetic Repository. The Journal of pediatrics, 190, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.055

- ↑ Etchevers, H. C., Vincent, C., Le Douarin, N. M., & Couly, G. F. (2001). The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development (Cambridge, England), 128(7), 1059–1068.

- ↑ Padget, D. H. (1948). The development of the cranial arteries in the human embryo. Contrib Embryol, 32, 205-261.

- ↑ Metry, D. W., Siegel, D. H., Cordisco, M. R., Pope, E., Prendiville, J., Drolet, B. A., Horii, K. A., Stein, S. L., & Frieden, I. J. (2008). A comparison of disease severity among affected male versus female patients with PHACE syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.009

- ↑ Siegel, D. H., Shieh, J., Kwon, E. K., Baselga, E., Blei, F., Cordisco, M., Dobyns, W. B., Duffy, K. J., Garzon, M. C., Gibbs, D. L., Grimmer, J. F., Hayflick, S. J., Krol, A. L., Kwok, P. Y., Lorier, R., Matter, A., McWeeney, S., Metry, D., Mitchell, S., Pope, E., … Broeckel, U. (2013). Copy number variation analysis in 98 individuals with PHACE syndrome. The Journal of investigative dermatology, 133(3), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.367

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Metry, D., Heyer, G., Hess, C., Garzon, M., Haggstrom, A., Frommelt, P., ... & Frieden, I. (2009). Consensus statement on diagnostic criteria for PHACE syndrome. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1447-1456.

- ↑ Pascual-Castroviejo, I. (1978). Vascular and nonvascular intracranial malformations associated with external capillary hemangiomas. In Proceedings of the XI. Symposium Neuroradiologicum (pp. 82-84). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- ↑ Frieden, I. J., Reese, V., & Cohen, D. (1996). PHACE syndrome: the association of posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities. Archives of dermatology, 132(3), 307-311.

- ↑ Boulinguez, S., Teillac‐Hamel, D., Bedane, C., Bennaceur, S., & De Prost, Y. (1998). Cervicofacial hemangioma and a minor sternal malformation: inclusion in PHACES syndrome?. Pediatric dermatology, 15(2), 119-121.

- ↑ Puvanachandra, N., Heran, M. K., & Lyons, C. J. (2008). Morning glory disk anomaly with ipsilateral capillary hemangioma, agenesis of the internal carotid artery, and Horner syndrome: a variant of PHACES syndrome?. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 12(5), 528–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.04.005

- ↑ Drolet, B. A., Frommelt, P. C., Chamlin, S. L., Haggstrom, A., Bauman, N. M., Chiu, Y. E., ... & MacLellan-Tobert, S. (2013). Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics, 131(1), 128-140.

- ↑ Frommelt, P., Juern, A., Siegel, D., Holland, K., Seefeldt, M., Yu, J., Uhing, M., Wade, K., & Drolet, B. (2016). Adverse Events in Young and Preterm Infants Receiving Topical Timolol for Infantile Hemangioma. Pediatric dermatology, 33(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12869