Acquired Ectropion Uveae

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Acquired ectropion uveae is an ocular condition characterized by the outward displacement or eversion of the uveal tissue in the eye.

Disease Entity

Disease

Acquired ectropion uveae (AEU), also known as acquired iris ectropion, does not have a specific code as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature.

H21.89 Other specified disorders of iris and ciliary body.

H21.1 Other vascular disorders of iris and ciliary body. Neovascularization of iris or ciliary body; Rubeosis iridis; Rubeosis of iris

Etiology

The uvea is the middle layer of the eye that consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Ectropion uveae specifically refers to the prolapse or protrusion of the iris pigment epithelium onto the anterior surface of the iris.[2][3][4] This condition is typically observed in the superior iris, near the pupil, but it can occur in other parts of the iris as well. Ectropion uveae can be congenital (present at birth) or acquired due to various factors.

The etiology of acquired ectropion uveae (AEU) encompasses a spectrum of factors, including ischemia, trauma, surgical procedures, inflammation, and neoplastic conditions.

AEU is most commonly associated with neovascularization of the iris (NVI)[2][3] and neovascular glaucoma (NVG)[5]. NVI, also referred to as rubeosis iridis, involves the development of blood vessels on the anterior surface of the iris due to neoplastic or ischemic conditions.[6] AEU has been observed in cases of iris melanoma, metastasis[7], and various retinal ischemic conditions, including but not limited to proliferative chronic retinal detachment[2], diabetic retinopathy[4], central retinal vein occlusion[8], and ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS, from carotid artery occlusive disease)[9].

However, AEU can also arise through mechanisms independent of significant NVI. Severe inflammation of the iris may lead to AEU. For instance, a case study by Darshana D. et al. reported AEU following uveitic glaucoma caused by juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and treated with combined surgery. In this case, excessive inflammation resulting from uveitis and surgery contributed to AEU.[4]

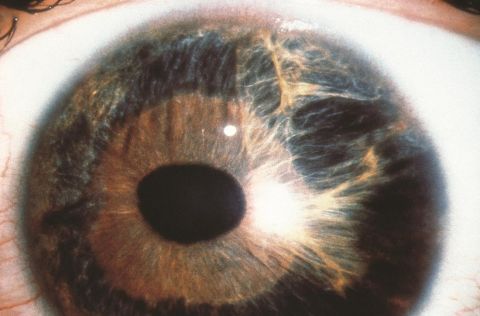

Another potential cause of AEU is Iridocorneal Endothelial (ICE) syndrome. The ICE syndrome, which is characterized by unilateral occurrence, a predominance in females, and a tendency to manifest later in life, involves the migration and multiplication of corneal endothelial cells beyond Schwalbe's line, the end of Descemet’s membrane.[10] This migration extends into the trabecular meshwork, eventually leading to secondary angle-closure glaucoma. Moreover, the proliferating corneal endothelial cells can affect the iris, resulting in diverse iris changes such as heterochromia, iris atrophy, corectopia, hole formation, and ectropion uveae.[11][12]

Direct ocular trauma can also contribute to AEU without other concurrent abnormalities. In a retrospective study spanning 10 years conducted by Vujica M. et al. at the University Eye Hospital in Belgrade, three cases of AEU with secondary glaucoma were presented. These cases were linked to blunt trauma to the eye, and no signs of iris inflammation, neoplasms, neovascularization, or dysgenesis were observed.[14]

Epidemiology

Acquired ectropion uveae is much more frequently encountered than its congenital counterpart, and the prevalence of AEU varies according to the underlying cause:

It is most commonly encountered during the angle-closure stage of neovascular glaucoma and absolute glaucoma (uncontrolled rise of IOP) patients.[15]

In iris melanoma, a retrospective study conducted over a 40-year span by Shields et al. identified ectropion uveae in 24 out of 317 patients (7.6%).[16] Its prevalence is even higher in cases of diffuse iris melanoma, with one study finding 21 out of 25 patients (84%) manifesting concurrent ectropion uveae.[17]

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is another common cause for AEU, with as many as 60% of ischemic CRVO cases being associated with NVI and AEU.[8]

Finally, ICE syndrome frequently leads to AEU. A retrospective analysis including 144 cases of ICE syndrome found that approximately one-fourth (24.6%) of these patients develop AEU, particularly prevalent in Cogan-Reese syndrome (54.2%, 13 out of 24 cases).[18]

Pathophysiology

Although acquired ectropion uveae can develop in many conditions, they probably share a common pathogenesis mechanism secondary to iris inflammation or neovascularization. The uveal tissue of the eye is pulled outwards because of the formation of a fibrovascular membrane on the anterior surface of the iris.[19] This contracting fibrovascular membrane with atrophy of the iris stroma causes tractional curling of the posterior pigment epithelium, iris sphincter muscle, and stroma around the pupillary margin to the anterior surface. This membrane formation may block the trabecular meshwork, increasing IOP and causing progressive secondary glaucoma.

Diagnosis

History

Acquired ectropion uveae may not cause any symptoms in mild cases. However, in more severe instances, the displaced uveal tissue can interfere with the normal flow of aqueous humor, leading to increased intraocular pressure. This can result in symptoms such as blurred vision, eye pain, redness, and light sensitivity.

Clinical diagnosis

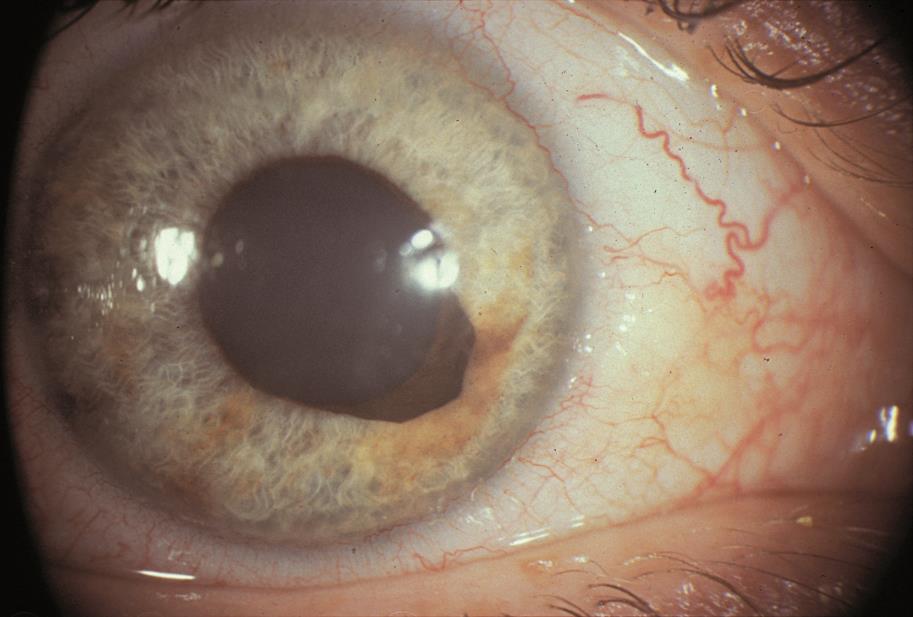

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy shows variable changes to the pupillary ruff, ranging from sectoral pigmentation at the pupillary margin, to a complete, flat pigmented ring around the pupil, extending variably toward the angle. The pupil itself may be distorted in shape and size due to traction, and the central opening may be displaced (corectopia).[20]

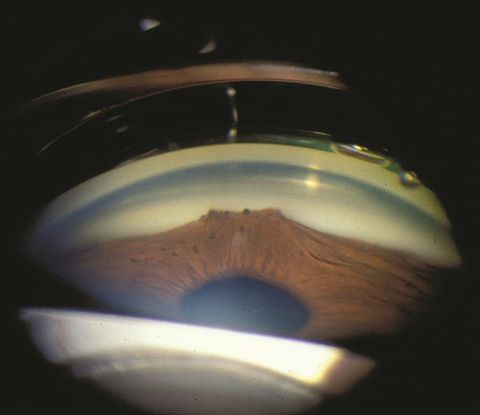

Gonioscopy may show new vessels in the angle of the anterior chamber, and anterior synechiae may be present.[21]

The cornea may be clear or edematous due to raised intraocular pressure, changes associated with ICE syndrome or other underlying etiologies.[10]

The intraocular pressure may be elevated due to secondary angle closure associated with the underlying etiologies for the AEU.[2][3][4][5]

Fundus evaluation will show the pathology that led to the formation of new vessels, including venous occlusions, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, chronic retinal detachment and arterial occlusions. Severe ocular inflammation may also be visualized.

Differential diagnosis

Congenital Ectropion Uveae/Congenital Iris Ectropion: Congenital ectropion uveae (CEU) arises due to the delayed development of neural crest cells. This results in the inability of the primordial endothelium in the anterior chamber to regress properly.[3] Conditions in which there is pigmented epithelium present on the anterior surface of the iris are frequently mistaken for AEU. Unlike AEU, in which the iris stroma and sphincter muscle become everted, in congenital cases, these structures remain normal. Furthermore, while AEU progresses until its underlying causes are addressed, most instances of congenital ectropion uveae tend to remain stable.[20]

Axenfeld Rieger Syndrome: Axenfeld Rieger syndrome (ARS) is a disorder due to the excessive proliferation, migration, and differentiation of neural crest cells.[2] This congenital abnormality exhibits an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is characterized by posterior embryotoxon—a condition where Schwalbe's line is positioned anterior to the corneal limbus. Clinical diagnosis often entails recognizing features like iris hypoplasia, corectopia, and polycoria, collectively indicative of Rieger's anomaly.[23] While it might present iris pigmentation resembling ectropion uveae, it's essential to distinguish ARS from CEU. Unlike CEU, this syndrome affects both eyes (bilateral), albeit with the possibility of an asymmetrical ocular phenotype.[24] Additionally, it accompanies systemic comorbidities such as glaucoma, sensorineural hearing loss, and various cardiac, endocrinological, craniofacial, and orthopedic abnormalities.[25]

Management

General treatment

The management of acquired ectropion uveae should be directed to the underlying cause. Patients with AEU have multiple comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular abnormalities, and in some cases, metastasis due to primary carcinomas elsewhere. However, most frequently, AEU is noted alongside NVI and NVG.

Medical therapy

The most common cause of NVI is posterior segment ischemia and retinal capillary nonperfusion. Intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents may cause regression of NVI and produce short-term control of neovascularization.

Associated neovascular glaucoma requires treatment with pressure-lowering drops. Adjunctive treatment with a short course of topical steroids may control inflammation to improve the outcome of subsequent surgery.

Many eyes with AEU may also have macular edema[26], which may be treated with topical steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intravitreal steroids, or intravitreal anti-VEGF agents.

Laser therapy

In addition to anti-VEGF therapy, pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) may be required to promote long-term regression of NVI and NVA. The management of peripheral retinal capillary nonperfusion with anti-VEGF and PRP usually causes prompt regression of the NVI upon initial treatment.[8]

Surgery

In cases of uncontrolled glaucoma secondary to NVG or ICE syndrome, filtration surgery such as trabeculectomy or glaucoma drainage devices may be required. Preoperative anti-VEGF agents may increase the success rate and reduce ocular hemorrhage in eyes with NVG.

Macular edema may be improved with pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peeling.[26]

In cases of non-clearing vitreous hemorrhage, pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser, with or without concurrent intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy may be required.

In OIS, management of carotid artery occlusive disease includes removing carotid plaque and stenting the carotid artery, which can cause a reversal of the ocular ischemic features.[9]

Prognosis

Eyes with AEU typically have fairly severe underlying disease. Accurate diagnosis and prompt medical or surgical treatment of the underlying etiology will lead to optimized patient outcomes. Close follow-ups are necessary to ensure stability of ischemia, inflammation, and intraocular pressure.

References

- ↑ Inferonasal mass. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/education/image/inferonasal-mass-4 Accessed January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Sridhar U, Tripathy K. Iris Ectropion Syndrome. StatPearls. Publishing; 2023. Accessed June 17, 2023.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580493/

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ectropion Uveae and Secondary Glaucoma. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published November 1, 2013. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/ectropion-uveae-secondary-glaucoma

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Daga D, Dubey S, Gandhi M. Acquired ectropion uveae: A case series. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2023 Feb 21;16(1):98-102. doi: 10.4103/ojo.ojo_24_22.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Senthil S, Dada T, Das T, Kaushik S, Puthuran GV, Philip R, Rani PK, Rao H, Singla S, Vijaya L. Neovascular glaucoma - A review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;69(3):525-534. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1591_20.

- ↑ Pagoulatos D, Georgakopoulos C. Rubeosis iridis. Pan Afr Med J. 2017 Nov 29;28:279. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.28.279.13717.

- ↑ Skalet AH, Li Y, Lu CD, Jia Y, Lee B, Husvogt L, Maier A, Fujimoto JG, Thomas CR Jr, Huang D. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Characteristics of Iris Melanocytic Tumors. Ophthalmology. 2017 Feb;124(2):197-204. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.10.003. Epub 2016 Nov 14.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 A randomized clinical trial of early panretinal photocoagulation for ischemic central vein occlusion. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group N report. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(10):1434-1444.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Tripathy K, Mazumdar S. Recurrent retinal and choroidal ischemia in a case of ocular ischemic syndrome. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2019;11:2515841419848926. doi:10.1177/2515841419848926

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Silva L, Najafi A, Suwan Y, Teekhasaenee C, Ritch R. The iridocorneal endothelial syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep-Oct;63(5):665-676. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.01.001.

- ↑ Walkden A, Au L. Iridocorneal endothelial syndrome: clinical perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr 9;12:657-664. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S143132.

- ↑ Iridocorneal Endothelial Syndrome and Secondary Glaucoma. Eyewiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published February 25, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Iridocorneal_Endothelial_Syndrome_and_Secondary_Glaucoma

- ↑ ICE syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/education/image/ice-syndrome-4 Accessed January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Markovic V, Vukovic D, Radosavljevic A, Marjanovic I. Acquired ectropion uveae and secondary glaucoma due to trauma: report of 3 cases. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2017 Jan 19;27(1):e1-e4. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000893.

- ↑ Senthil S, Dada T, Das T, Kaushik S, Puthuran GV, Philip R, Rani PK, Rao H, Singla S, Vijaya L. Neovascular glaucoma - A review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;69(3):525-534. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1591_20.

- ↑ Shields CL, Kaliki S, Shah SU, Luo W, Furuta M, Shields JA. Iris melanoma: features and prognosis in 317 children and adults. J AAPOS. 2012 Feb;16(1):10-6.

- ↑ Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC, Honavar SG. Diffuse iris melanoma: a report of 25 cases. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(8):1553-1560. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01104-1

- ↑ Ye WQ, Deng YX, Zuo JJ, Zhang SD, Wang HO, Li JY, Zheng QX, Liang YB, Chen W. [Clinical characteristics of 114 patients with iridocorneal endothelial syndrome]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi. 2022 Jan 11;58(1):35-40. Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112142-20201231-00859.

- ↑ Thomas John, Joseph W. Sassani, Ralph C. Eagle, The Myofibroblastic Component of Rubeosis Iridis, Ophthalmology, Volume 90, Issue 6, 1983, Pages 721-728, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(83)34520-6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 20.0 20.1 Congenital Ectropion Uveae. Eyewiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published February 9, 2023. Accessed Augest 10, 2023.

- ↑ Kuo IC, Cunningham ET. Ocular neovascularization in patients with uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2000;40(2):111-126. doi:10.1097/00004397-200004000-00009

- ↑ Indocorneal-endothelial syndrome. American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/education/image/indocorneal-endothelial-syndrome-2 Accessed January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Axenfeld Rieger Syndrome. Eyewiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published February 9, 2023. Accessed Augest 10, 2023. https://eyewiki.aao.org/Axenfeld_Rieger_Syndrome

- ↑ Puthalath AS, Agrawal A, Rana R, et alA case of Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome (ARS) with asymmetric ocular phenotypes and left glaucomatous optic atrophyBMJ Case Reports CP 2020;13:e237224.

- ↑ Chang TC, Summers CG, Schimmenti LA, et al. Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome: new perspectivesBritish Journal of Ophthalmology 2012;96:318-322.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Jackson TL, Nicod E, Angelis A, Grimaccia F, Pringle E, Kanavos P. PARS PLANA VITRECTOMY FOR DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Synthesis of Safety Literature. Retina. 2017 May;37(5):886-895. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001280.