Congenital Ectropion Uveae

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Congenital ectropion uveae (CEU) (i.e. congenital iris ectropion syndrome, primary iris pigment epithelial hyperplasia) is a rare disorder with unilateral anterior chamber dysgenesis that commonly leads to unilateral secondary glaucoma in the mid-teenage years with associated morbidity and possible blindness. It is characterized by ectropion uveae that is present since birth and subsequent glaucoma due to trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal dysgenesis.

Background

The term congenital ectropion was first introduced by Colsman in 1869[1], but it was later discovered that his description was actually iris flocculi. The first authors to accurately describe congenital ectropion were Wicherkiewicz in 1891[2] and Spiro in 1896[3].

Disease Entity

Congenital ectropion uveae (CEU) does not have a specific code as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature. We recommend the following codes as appropriate.

H21.89 Other specified disorders of iris and ciliary body

Q15.0 Congenital glaucoma

Etiology

Ectropion uveae can be divided into two main categories: acquired and congenital. The differences are based primarily on the etiology of the ectropion. Acquired ectropion is more common than congenital, and is associated with tractional forces secondary to a fibrovascular membrane spreading across the anterior surface of the iris. As this membrane contracts, the posterior pigmented iris epithelium is pulled around to the anterior iris surface. This fibrovascular membrane (or neovascularization of the iris) can be from multiple sources with the most common etiologies being proliferative diabetic retinopathy and central retinal vein occlusion, or less commonly inflammatory, neoplastic, or ischemic processes involving the iris. On the other hand, congenital ectropion, is thought to be the result of failure of regression of a primordial endothelium in the anterior chamber. Congenital ectropion is often nonprogressive whereas acquired will usually progress unless the underlying process is adequately treated.

Risk Factors

CEU does not have a specific genetic inheritance, and most commonly is not related to a systemic condition. However, NF-1 and other less common syndromes (facial hemihypertrophy, Prader-Willi syndrome) have been reported to have an association with CEU (see below)[4].

Pathophysiology

CEU is thought to be caused by reactive hyperplasia of the iris pigment epithelium. This hyperplasia is incited by failure of regression of the primordial endothelium that lines the anterior chamber. It is thought that the failure of regression is secondary to developmental arrest of neural crest tissue in utero. This also leads to anterior iris insertion and angle dysgenesis. The trigger for arrest of migration has not been identified to this date. Some authors postulate that it may be related to a primary vascular insult that leads to defective neural crest cell migration. Harasymowycz PJ et al. presented a case of CEU, which on histopathologic examination was found to have a fibrovascular membrane in the anterior iris stroma[5]. This brings up the possibility that a vascular insult could be the cause of the defect in neural crest migration. Such arrest of neural crest migration has been demonstrated to occur due to a vascular insult in an embryonal study of the heart in hypoxia-inducible factor-1 knockout mice[6].

Ectropion Uveae and Neurofibromatosis type 1

Glaucoma is a known ocular complication associated with NF-1. Ectropion uveae associated with NF-1 is thought to occur secondary to endothelialization of the iris leading to tractional forces resulting in ectropion uveae. These changes along with iridocorneal adhesions may lead to glaucoma. It is known that orbital involvement of NF-1, especially a lid neurofibroma, increases the odds of developing glaucoma. Similarly, the presence of ectropion uveae is closely correlated with the risk of developing glaucoma. In a cohort of 56 NF-1 patients, 13 had glaucoma, and of these, 8 of them had ectropion uveae. Of the 43 patients without glaucoma, only four had ectropion uveae, and all four were found to have partial angle closure[7]. Unfortunately, visual prognosis of patients with glaucoma and NF-1 is poor. In the aforementioned study by Morales et al., all of the patients that were able to give a reliable visual acuity were either legally or completely blind.[7]

Diagnosis

CEU is largely a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of ectropion uveae and angle dysgenesis that has been present since birth with no other known underlying causes of ectropion uvea present.

History

A detailed family history should be assessed to evaluate for any possible related systemic syndromes such as NF-1. A history of anisocoria may be elucidated that is often noted in infancy or early childhood. Careful review of old photographs can reveal the longstanding nature of subtle anisocoria. Given the later onset of glaucoma, the classic triad of epiphora, photophobia, and blepharospasm associated with congenital glaucoma is often not present. Some patients may present with late symptoms of secondary glaucoma or elevated intraocular pressure such as headaches, blurred vision, or eye pain.

Clinical diagnosis

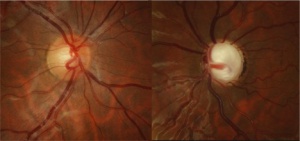

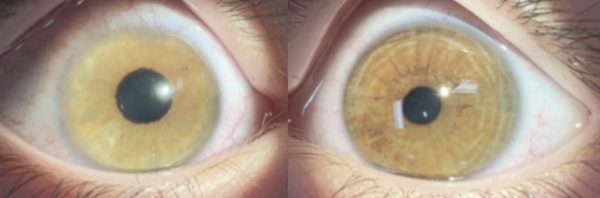

CEU most commonly presents unilaterally (although bilateral cases have been described)[4]. Typical clinical findings include a glassy, smooth, cryptless iris surface, iris stromal atrophy, proliferation of iris pigment epithelium onto the anterior surface of the iris, and glaucoma. The pupil is typically round and reactive to light but may grossly appear irregular because of the abnormal iris pigment epithelium. In addition, mild ptosis may be noted in the affected eye with normal levator function. This is likely related to the neural crest origin of Müller's muscle. Gonioscopic findings of CEU most often include an anterior iris insertion, which can extend almost to Schwalbe’s line (but there should be no PAS or peripheral anterior synechia or other pathology that extends past). Secondary glaucoma is a very common complication of CEU, although it tends to occur at a later age, often diagnosed in late childhood or early adolescence. The range of diagnosis of glaucoma was from 7 months to 42 years in two case reports by Ritch R et al., and Dowling JL Jr., et al[4][8]. Clinical findings usually demonstrate an enlarged cup-to-disc ratio in the affected eye, with significant asymmetry compared to the unaffected eye. Most often, this is related to a significant increase of intraocular pressure (IOP) in the affected eye. On gonioscopy, there is a high or anterior iris insertion, which has been reported to extend almost to Schwalbe’s line[4][8].

Diagnostic procedures

As above, CEU is a clinical diagnosis, and relies on slit lamp biomicroscopy to detect the characteristic abnormalities of the anterior segment as well as findings on gonioscopy.

The main diagnostic test for detecting glaucoma in patients with CEU is measurement of elevated IOP. Similar to congenital glaucoma, the diagnostic technique will depend on the patient’s age and ability to cooperate. In infants, an accurate IOP can be measured with a Perkins applanation tonometer or tonopen when sleeping or feeding while supine. The Icare rebound tonometer can also be used to measure an infant’s IOP. In children with CEU, if an accurate IOP cannot be obtained, a sedated exam may be required[9]. In older, cooperative patients, standard Goldmann applanation tonometry can be performed.

Additional diagnostic procedures to confirm the presence of glaucoma should be pursued in children with CEU. A careful optic nerve head examination with disc photos is critical to identify glaucomatous optic nerve cupping or rim thinning. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the optic disc can be used to assess for retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning and Humphrey visual field (HVF) testing can evaluate for characteristic visual field loss. These tests rely on the patient’s ability to cooperate, so may not be appropriate for all patients with a diagnosis of CEU.

Differential diagnosis

Iridocorneal endothelial syndrome (ICE): Similar to CEU, ICE is a unilateral condition that may result in anisocoria and corectopia. Unlike CEU, ICE commonly occurs in middle-aged adults with a preponderance of women being affected. However one case of ICE has been reported in a child. Depending on the clinical variant of ICE, predominantly corneal (edema) or iris (polycoria, corectopia, ectropion uveae vs nodules) findings may be seen. High PAS above Schwalbe’s line is pathognomonic of ICE, and although a high anterior iris insertion is common in CEU, this would not extend above Schwalbe’s line.

Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome (ARS): Similar to CEU, ARS is associated with arrest in neural crest development with resulting anterior segment abnormalities. Unlike CEU, ARS is bilateral, and associated with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. It can be associated with other ocular findings such as posterior embryotoxon, iris atrophy, corectopia, or polycoria. Facial abnormalities, such as maxillary hypoplasia or dental defects, may also be found in ARS as opposed to CEU.

Primary congenital glaucoma (PCG): Similar to CEU, PCG would present with elevated IOP, and increased cup-to-disc ratio on exam. Unlike CEU, PCG is typically bilateral (can be asymmetric) and commonly presents soon after birth with the classical triad of epiphora, photophobia, and blepharospasm. Corneal edema and buphthalmos are also common findings of PCG not commonly seen in CEU.

Management

There is no known treatment for CEU. Treatment for patients with CEU is focused on treating the secondary glaucoma that is so frequently associated.

The treatment of glaucoma in patients with CEU usually requires surgery, although medical therapy may be initiated until more definitive treatment can be pursued.

Medical therapy

Topical IOP lowering medications that are appropriate in children include beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs), and prostaglandin analogues. Alpha-2 agonists are effective in reducing IOP however, brimonidine is contraindicated in children younger than two due to respiratory and central nervous system depression. These agents should therefore be avoided until the approximate age of 8 years old. Apraclonidine can be useful for short-term IOP reduction, but it has a high incidence of tachyphylaxis and allergy in young children. Although less likely, Apraclonidine can also produce somnolence and respiratory depression in infants and young children.

Surgery

Glaucoma in children with CEU largely requires surgical management, similar to PCG. However, the choice of surgery is different than PCG due to severe angle dysgenesis in CEU. As a result, goniotomy in CEU has a much lower success rate than in PCG[10][11]. In most cases, glaucoma filtration surgery with or without antimetabolites is the treatment of choice to control IOP[11][12].

In a case series of goniotomy in CEU by Dowling et al., three patients received six goniotomies, and even with adjunctive medication, the IOP was not adequately controlled[8]. In the same case report, seven of nine patients required trabeculectomy.

Due to the rare nature of this disorder, there is no follow-up data on treatment success rates in CEU-associated glaucoma. However, we would expect these results to be similar for other secondary pediatric glaucomas. In those cases, trabeculectomy alone has a 30 to 35 percent success rate over long-term follow-up. With adjunctive mitomycin C (MMC), the procedural success rate increases to 52 to 95 percent, with a 60 percent success rate at two years.

Glaucoma drainage devices have a similar success rate as trabeculectomy with MMC: 44 to 95 percent success rate with 60 to 65 percent success at two years. However, adjunctive medical therapy is often necessary to maintain IOP control. In refractory cases, cyclodestructive procedures may become necessary, but these procedures may have limited success and a high complication rate[13].

Prognosis

Visual morbidity in CEU is closely related to the severity of glaucoma. Thus, visual prognosis is largely dependent on early diagnosis and treatment of the patient’s elevated IOP. There is no relationship that has been found between the severity of ectropion uveae and angle dysgenesis/glaucoma[14]. Neonatal-onset congenital ectropion uveae is characterized by bilateral severe glaucoma at birth that may be resistant to treatments incluiding surgery.[15][16] The corneal clarity and outcomes are worse than primary congenital glaucoma. Multiple mutations in CYP1B1 have been described in this disease.[16]

References

- ↑ Colsman. Papilloma Iridis (physiologische thiera ̈hnilche Bildung der Iris). Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1889:7-53.

- ↑ Wicherkiewicz B. Contribution to the knowledge of the Ectropion Uveae congenitum. Graefe's Arhiv for Ophthalmology 1891; 37: 204-07. (Translated from German to English).

- ↑ Spiro G. Ein Fall von Ectropion uveae congenitum. Centralbl Prakt Augenheilkd. 1896; 20:310-311.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ritch R, Forbes M, Hetherington J Jr, Harrison R, Podos SM. Congenital ectropion uveae with glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:326-31.

- ↑ Harasymowycz PJ, Papamatheakis DG, Eagle RC, Wilson RP. Congenital ectropion uveae and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124:271-3.

- ↑ Compernolle V, Brusselmans K, Franco D, etal. Cardia bifida, defective heart development and abnormal neural crest migration in embryos lacking hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:569-579.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Morales J, Chaudhry IA, Bosley TM. Glaucoma and globe enlargement associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(9):1725-30.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Dowling JL Jr, Albert DM, Nelson LB, Walton DS. Primary glaucoma associated with iridotrabecular dysgenesis and ectropion uveae. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:912-21.

- ↑ Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2016-2017; pp12.

- ↑ Mandal AK. Late onset unilateral primary developmental glaucoma associated with iridotrabecular dysgenesis, congenital ectropion uveae and thickened corneal nerves: A new neural crest syndrome? Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999;30:567-70.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Wolter JR, Butler RG. Pigment spots of the iris and ectropion uveae with glaucoma in neurofibromatosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1963;56:964-73.

- ↑ Roth H, Shaffer RN. Neurofibromatosis and glaucoma. In: Bellows JG, ed. Contemporary Ophthalmology: Honoring Sir Stewart Duke- Elder. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1972:180-189.

- ↑ Beck AD. Diagnosis and management of pediatric glaucoma. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2001;14(3):501-512.

- ↑ Wilson ME. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1990;27(1):48-55.

- ↑ Kaushik S, Dhingra D, Vibha B, Saini A, Gupta G, Snehi S, Singh N, Thattaruthody F, Pandav SS. Neonatal-Onset Congenital Ectropion Uveae: A Distinct Phenotype of Newborn Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar;223:83-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.10.001. Epub 2020 Oct 9. PMID: 33045217.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Kaushik S, Choudhary S, Kaur A, Srivastava P, Pokharel B, Akella M, Pandav SS. Neonatal-onset Congenital Ectropion Uveae may be caused by a distinct CYP1B1 pathological variant. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jan 24:S0002-9394(22)00015-0. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.01.014. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35085548.