Ectasia Risk in Topography

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

LASIK and PRK induced ectasia is preventable if the preoperative topographic and pachymetry indexes for high-risk are identified on time.[1][2][3]

Disease Entity

Refractive surgery induced ectasia is probably the most feared complication of laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). It presents as a progressive steepening and thinning of the cornea, is considered to be irreversible and reduces uncorrected and often spectacle-corrected visual acuity.[3] Although the prevalence of postoperative ectasia is unknown, the reported prevalence rates vary from 0.02% to 0.6% .[4][5]

Risk factors for the development of post-LASIK/PRK ectasia include a personal or family history of keratoconus (KC), abnormal corneal topography (form fruste keratoconus), high myopia, low-residual stromal bed (RSB), excessive stromal ablation (>100 microns), deep primary keratotomy resulting in a thick corneal flap and low preoperative corneal thickness (<500 microns).[3] [6][7][8]

Even when risk factors for ectasia after refractive surgery have been identified, reports of individuals developing ectasia without any of the proposed risk factors have emerged, this specific group of patients have shown a tendency to be younger.[3][9][10][11]

Etiology

Corneal ectasia induced by excimer laser refreactive surgery is though to be the result of the alteration of the corneal surface and anterior stroma in corneas with previous mechanical abnormalities.[12] Histologic and ultrastructural findings explain the pathophysiology of post-LASIK or posr-PRK ectasia by interlamellar and interfibrillar biomechanical slippage induced by excimer laser disruption (interlamelar and interfibrillar fracture) and not to primary collagen fibrillar failure.[12] Beside geometric corneal parameters, new techniques permit a better understanding of the corneal bio-mechanics, in order to better predict the corneal response to surgical or therapeutic interventions and to assist in the detection of early KC. [13][14][15]

Risk Factors

There is an integrated relationship between preoperative corneal thickness, ablation depth, and flap thickness in determining the relative amount of bio-mechanical change that has occurred after a LASIK/PRK procedure.[16][17][18][19][20][21] Since ther first reported cases of corneal ectasia after LASIK, numerous authors have reported the characteristics of the eyes of these patients making an emphasis on preoperative high myopia, RSB thickness lower than 250 microns, low preoperative corneal thickness (<500 microns) and abnormal topography (forme fruste keratoconus).[22][23][24][25] Randleman et al, compared normal uneventful LASIK patients with those develping corneal ectasia after LASIK or PRK and observed that the latter had significant abnormal preoperative corneal topographies, were younger (< 34 years), were more myopic (>8 diopters of mean refractive spherical equivalent), had thinner corneas before surgery (521 microns) and had less RSB thickness (256 microns).[3] Logistic regression analysis on their data showed abnormal topography as the most significant factor that discriminated cases from controls. [1] [3]

More recently Santhiago et al, found that the perecent of tissue altered (PTA)≥ 40% during LASIK (derived from [PTA = (FT + AD)/CCT] where FT is flap thickness, AD is ablation depth and CCT is central corneal thickness) is strongly associated with the development of ectasia in eyes with otherwise normal topography.[16]

Down syndrome, family history, connective tissue disorders, ocular allergy, and mechanical factors such as eye rubbing and floppy eyelid syndrome, have also been identified as risk factors in ectatic disease pathology.[26]

General Pathology

Pointing out a patient with FFK and early KC is of major importance in the preoperative assessment, as most of the refractive procedures are contraindicated in patients with an ectasic preoperative condition due to the high-risk of induction and/or progression the ectasia after the procedure.[27]

Pathophysiology

The pathologic process of keratoconus can involve every layer and tissue of the cornea. The central epithelial layer has been consistently found with variable thinning. [28]

There is evidence in specular microscopy of enlargement of the superficial cells, findings not revealed in long term hard contact lens wearer.[29]

Electron microscopic studies have proved the Z-shaped pattern interruptions at the level of Bowman´s layer, it is believed are caused by brakes in the epithelial layer with posterior growing of the epithelial layer into Bowman´s layer and collagen growing anteriorly into the epithelial layer.[30]

The fragmentation observed in the Bowman´s layer with the electron microscopy scanner tend to be specific of keratoconus, and it is believed to be the initial change leading the ectasic disease.[31]

One of the typical lesions in keratoconus is the Fleischer ring, found at the base of the cornea. Classical studies performed with electron microscopy demonstrate ferritin particles distributed between epithelial cells, participating in the formation of reticulated, sub-epithelial and anterior stromal scars.[32]

The breaks observed in Bowman's layer with light and electron microscopy are considered in the spectrum of clinical findings in keratoconus. And it is believed these spaces may be later filled with scar tissue. [33]

There is evidence that the Brakes found at Bowman´s layer occurred more often in oval, sagging cones in comparison with round cones.[34]

As there are studies that demonstrate evidence of short brakes in Bowman´s layer in normal corneas. Kass-Hansen suggested that those brakes were a secondary phenomenon, not necessarily participating in the pathogenesis of the keratoconus.[35]

Atypical hystopathogical variant has been described, where brakes in Bowman´s layer are not present, although clinically is the same pathology. Among different histopathologic variants the scarring of Bowman´s layer and anterior stroma positively correlate with fragmentation of collagen fibers and fibroblastic activity.[28][36]

The pathology of collagen fibrils in keratoconus has been well studied by Pouliquen et al. They have found normal-sized collagen fibers; however, the number of collagen lamellae was abnormally low. The number found within the cone was less than half (41%). [37][38]

It has been suggested that collagen lamellae released from their attachments to Bowman´s layer and become free to slide. This results in thinning without collagenolysis. [39]

Significant alteration of the normal orthogonal arrangement of the collagen fibrils found in keratoconus may be related to this inherent corneal weakness. This may also explain the association of eye rubbing with keratoconus. [40]

Fine granular material and extracellular microfibrillary material are also found in the stroma and are likely synthesized by stromal keratocites. [37]

Endothelial cell pleomorphism and polymegathism ocurr in keratoconus. The degree of polymegathism does not differ significantly from normal controls with a similar contact lens history, suggesting that these changes may be related to long-term contact lens wear rather than keratoconus. [41]

Patterns of endothelial damage vary from isolated cell membranolysis to denudement of Descemet´s membrane. More damage occurs at the base of the cone than at the apex and correlates with the severity and the duration of the disease.[42]

Diagnosis

The article published by Marconi Santhiago, propose a metric for calculating the ectasic risk in patients where LASIK is to be performed. The percentage of tissue altered (PTA) that describes the interaction between de flap thickness (FT), the ablation depth (AD) and the central corneal thickness (CCT) interaction during excimer laser refractive surgery, is described in the following equation: PTA = (FT + AD) / CCT . This metric formula represents a more accurate way of calculating the risk of corneal ectasia after LASIK than taking into account the individual components that comprise it.[16]

Using the Orbscan technology Randleman et al. Propose the following risk factors for ectasia in order of importance:

- Abnormal preoperative topography

- Low Residual Stromal Bed (RSB) thickness

- Young age

- Low preoperative corneal thickness

- High myopia.

A screening strategy that weighs all of these factors was proposed: Ectasia Risk Factor Score System. Given a score between 0 to 4 to each one of the factors. [1]

The scoring is a useful but still controversial index for preoperative LASIK candidates.

There are two main videokeratographies software's used to evaluate pre-operative ectatic risk in the first place the one developed by Rabinowitz[43] and in second place the one developed by Maeda and Klyce at the LSU Eye Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.[44][45]

Using the Keratoconus Prediction Index (KPI) The system developed by Maeda and Klyce was able to differentiate keratoconus from a wide variety of other pathologies with a false positive rate of 98.7% and a false negative rate of 98.4%.[45]

The Rabinowitz software differs from the Maeda-Klyce system in three aspects:

- Attempts to differentiate keratoconus from healthy corneas, not from other pathologies in a non-contact lens wearing patient.

- Evaluates both eyes.

- The indices were developed from videokeratographs of patients with clinical signs of keratoconus.[43]

History

Marc Amsler In 1938, with a photographic placido disk, was the first to describe early corneal topographic changes in keratoconus before clinical or bio-microscopic signs could be noted. His classical studies of keratoconus documented the progression of the disease, from minor corneal surface changes to clinically identifiable keratoconus.

He classified keratoconus into clinical stages and an earlier latent stage identifiable only with the placido disk evaluation of corneal topography. The early stages were subdivided into two categories:

- Keratoconus fruste. In which there is a 1–4 degree deviation of the horizontal axis of the placido disk.

- Early or mild keratoconus. Which has a 4–8 degree deviation.

Amsler reexamined 286 eyes 3–8 years after the diagnosis, and only 20%, including 66% of the latent cases, show progression.

Progression was most likely to occur in patients between 10 and 20 years of age and decreased tendency to progression between ages 20 and 30, and low incidence of progression after 30 years old.[46]

Levene suggests that instrument tilt or poor alignment (hand held needed) of the keratoscope may result in incorrect observations of the corneal shape in the horizontal axis. Creating intra-observer and inter-observer discrepancies. [47]

In the 70´s Donaldson published a new technique for keratography: The photokeratoscope produces a topographic record of 55–80% of the total corneal contour, but it provides little information about the central 2-3 mm of the cornea.[48] Rowsey et al. used this instrument to study keratoconus in 827 patients.[49]

The ophthalmometer or keratometer, provides information from 3 points approximately 3 mm apart, calculating anterior corneal curvatures being a simple and useful tool for detecting keratoconus. Typically showing a progressive central or inferior steepening.

Krachmer et al. documented increasing in corneal curvature over time using the keratometer as a sensitive indicator of keratoconus.[50]

In 1984 the classic publication of Klyce et al. set the basis for the later development of computer-assisted videokeratoscopes algorithms. The computed process demonstrate to be a useful quantitative method with which to determine corneal shape, for clinical evaluation particularly in corneal surface irregularities.[51]

Current corneal imaging modalities: Scheimpflug, optical coherence tomography (OCT) offer more information than were previously available with placido based anterior corneal analysis. This new tomographic information allows for earlier identification of disease and has changed our perception of what constitutes keratoconus, improving the specificity to exclude false positive cases.[52]

OCT and Scheimpflug photography allows measurements of both the anterior and posterior cornea, corneal thickness maps, providing greater corneal coverage than possible with videokeratoscopes.[53]

Of these, rotating Scheimpflug photography currently provides the most useful information for diagnosing early ectatic change. It is also a technique that is rapid and easy to perform, which would be a requisite for use as a screening tool.[54][55][52]

Clinical diagnosis

In 2015 international cornea specialist gathered efforts to define key points in the global consensus on keratoconus and ectatic diseases.[26] According to Dr. Rapuano Moderate to severe KC is easy to diagnose clinically “You can see it at the slit lamp; you don’t even need topography.” But to recognizing mild, subclinical disease it is necessary the information of computed systems such as Scheimpflug imaging or OCT, which can detect posterior corneal abnormalities.

The panelist group agreed that the mandatory findings for KC diagnosis include posterior corneal elevation abnormalities, in addition to abnormal distribution of corneal thickness and noninflammatory corneal thinning.[26]

Keratoconus, from greek: (kerato- horn, cornea; and konos cone) is a condition in which the cornea assumes a conical shape due to noninflammatory thinning of the stroma, Producing an irregular astigmatism, myopia, and protrusion, progressively deteriorating vision. Tipically affecting both eyes. [50]

Munson’s sign and Rizzuti’s classical clinical signs are observed in latter stages. Munson’s sign is a V-shaped deformation of the lower lid produced by the corneal conic protrusion in down-gaze. Rizzuti’s sign is a sharply focused beam of light near the nasal limbus.[56]

Fleischer ring are pigmented rings in the peripheral cornea.[57] Resulting from iron deposition in basal epithelial cells, in the form of hemosiderin. They are usually yellowish to dark-brown, and may be complete or broken. Fleischer ring is present in most keratoconus corneas whereas prominent nerves are less frequent and specific for keratoconus.[58][59]

Diagnostic procedures

It has been estimated that up to 6% of patients with some sort of pre-clinically ectatic condition show up in clinical settings for refractive evaluation. [60][61][62]

Videokeratographic classical patterns for keratoconus rely mainly on three characteristics:

- Increased area of corneal power surrounded by concentric areas of decreasing power.

- Asymmetric inferior-superior power.

- Skewing of the steepest radial axes above and below the horizontal meridian.

Keratometry

Central 3 mm curvature zone readings are a very useful tool in pre-operatory evaluation. Manual keratometry is very sensitive indicator of astigmatism. Increased 0.5 diopters or more per year should make the clinician to be conservative and gather more information over time.[63]

Computed Topography.

Up to date the most important element of pre-operative evaluation. The mapping of the corneal surface, renders the calculated corneal dimensions.

There are two principal corneal topographic techniques:

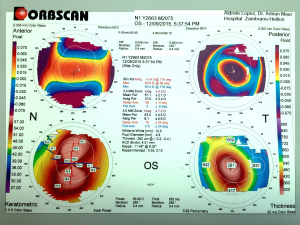

- Pentacam: Scheimpflug rotatory camera (Oculus Inc, Wetzlar, Germany).

- Orbscan: Slit lamp scanner monochromatic blue light based (Bausch & Lomb, Technolas, Müngen, Germany).

Optic Coherence Tomography (OCT)

RTVue: Infrared based high definition imaging technique (Optovue, Inc, Fremont, CA.)

Differential diagnosis

Meticulous slit lamp examination may distinguish from keratoglobus, pellucid marginal degeneration and Terrien marginal degeneration. But topographic evidence is necessary in early presentations or non typical cases.[64]

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration.

Typically described by a peripheral band of thinning of the inferior cornea, there is an uninvolved area between the thin corneal area and sclero-corneal limbus. Central corneal thickness usually normal.

As well as keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration is a progressive condition affecting both eyes. Most of the times the affection tends to be asymmetric.

The topographic pattern of the cornea classically resemble a butterfly, with against the rule astigmatism. [62]

Terrien Marginal degeneration

Terrien marginal degeneration is a slow-progressing, bilateral asymmetric degeneration of the peripheral cornea. Male over 40 years are more commonly affected. Stromal thinning, vascularization, lipid deposition, and against-the-rule astigmatism are classic signs. Though typically noninflammatory, a variant form characterized by prominent inflammation exists. [65]

Keratoglobus

Keratoglobus is a rare bilateral disorder in which the entire cornea is thinned most markedly near the corneal limbus, in contrast to the localized thinning centrally or paracentrally in keratoconus. [50]

Most often keratoglobus is a congenital disease, but it may be secondarily acquired. This corneal pathology tend to produce extreme myopia, irregular astigmatism, and corneal scarring due to hydrops.[66]

Additional Resources[67]

- http://www.aao.org (American Academy of Ophthalmology)

- http://www.nkcf.org (NationalKeratoconusFoundation)

- https://nei.nih.gov/health/cornea (National Eye Institute)

- https://clinicaltrials.gov (Clinical trials for corneal diseases)

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Randleman JB, Trattler WB, Stulting RD. Validation of the Ectasia Risk Score System for Preoperative Laser in Situ Keratomileusis Screening. American journal of ophthalmology. 2008;145(5):813-818. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.033.

- ↑ Randleman JB, Russell B, Ward MA, Thompson KP, Stulting RD. Risk factors and prognosis for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:267–75. [PubMed]

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Stulting RD. Risk Assessment for Ectasia after Corneal Refractive Surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37–50. [PubMed]

- ↑ Binder PS. Analysis of ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis: risk factors. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007; 33(9):1530–1538.

- ↑ Chen MC, Lee N, Bourla N, Hamilton DR. Corneal biomechanical measurements before and after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008; (34)11:1886–1891.

- ↑ Ortiz D, Piñero D, Shabayek MH, Arnalich-Montiel F, Alió JL. Corneal biomechanical properties in normal, post-laser in situ keratomileusis, and keratoconic eyes. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2007;33(8):1371–1375.

- ↑ González-Méijome JM, Villa-Collar C, Queirós A, Jorge J, Parafita MA. Pilot study on the influence of corneal biomechanical properties over the short term in response to corneal refractive therapy for myopia. Cornea. 2008;27(4):421–426.

- ↑ Kirwan C, O’Keefe M. Corneal hysteresis using the Reichert ocular response analyser: findings pre- and post-LASIK and LASEK. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2008;86(2):215–218.

- ↑ Argento C, Cosentino MJ, Tytiun A, et al. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2001;27:1440–8.

- ↑ Wang JC, Hufnagel TJ, Buxton DF. Bilateral keratectasia after unilateral laser in situ keratomileusis: a retrospective diagnosis of ectatic corneal disorder. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:2015–8

- ↑ Piccoli PM, Gomes AA, Piccoli FV. Corneal ectasia detected 32 months after LASIK for correction of myopia and asymmetric astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1222–5.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Dawson DG1, Randleman JB, Grossniklaus HE, O'Brien TP, Dubovy SR, Schmack I, Stulting RD, Edelhauser HF. Corneal ectasia after excimer laser keratorefractive surgery: histopathology, ultrastructure, and pathophysiology.Ophthalmology 2008;115(12):2181-2191

- ↑ Garcia-Porta, N., Fernandes, P., Queiros, A., Salgado-Borges, J., Parafita-Mato, M., & González-Méijome, J. M. (2014). Corneal Biomechanical Properties in Different Ocular Conditions and New Measurement Techniques. ISRN Ophthalmology, 2014, 724546. http://doi.org/10.1155/2014/724546

- ↑ Luce DA. Determining in vivo biomechanical properties of the cornea with an Ocular Response Analyzer. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2005;31(1):156–162.

- ↑ Piñero DP, Alcón N. In vivo characterization of corneal biomechanics.J Cataract Refract Surg. 2014 Jun;40(6):870-87.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 Santhiago MR, Smadja D, Gomes BF, Mello GR, Monteiro ML, Wilson SE, Randleman JB. Association between the percent tissue altered and post-laser in situ keratomileusis ectasia in eyes with normal preoperative topography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jul;158(1):87-95.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.04.002. Epub 2014 Apr 13. PubMed PMID: 24727263.

- ↑ Santhiago MR, Wilson SE, Hallahan KH, et al. Changes in custom biomechanical variables after femtosecond laser in situ keratomileusis and photorefractive keratectomy for myopia. J Cataract Refract Surg. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.11.030.

- ↑ Smadja D, Santhiago MR, Mello GR, Roberts CJ, Dupps WJ Jr, Krueger RR. Response of the posterior corneal surface to myopic laser in situ keratomileusis with different ablation depths. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38(7): 1222–1231.

- ↑ Reinstein DZ, Archer TJ, Randleman JB. Mathematical model to compare the relative tensile strength of the cornea after PRK, LASIK, and small incision lenticule extraction.J Refract Surg 2013;29(7):454–460.

- ↑ Randleman JB, Hebson CB, Larson PM. Flap thickness in eyes with ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2012;38(5):752–757.

- ↑ Saad A, Gatinel D. Bilateral corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis in patient with isolated difference in central corneal thickness between eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg 2010;36(6):1033–1035.

- ↑ Seiler T, Koufala K, Richter G. Iatrogenic keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg 1998;14:312–7.

- ↑ Seiler T, Quurke AW. Iatrogenic keratectasia after LASIK in a case of forme fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998;24:1007–9.

- ↑ Buzard KA, Tuengler A, Febbraro JL. Treatment of mild to moderate keratoconus with laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:1600 –9.

- ↑ Geggel HS, Talley AR. Delayed onset keratectasia following laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25: 582–6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 26.2 Gomes JA, Tan D, Rapuano CJ, Belin MW, Ambrósio R Jr, Guell JL, Malecaze F, Nishida K, Sangwan VS;Global consensus on keratoconus and ectatic diseases. Group of Panelists for the Global Delphi Panel of Keratoconus and Ectatic Diseases. Cornea. 2015 Apr;34(4):359-69. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000408. PMID: 25738235

- ↑ Lafond G, Bazin R, Lajoie C. Bilateral severe keratoconus after laser in situ keratomileusis in a patient with forme fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001 Jul;27(7):1115-8. PubMed PMID: 11489585.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Scroggs MW, Proia AD. Histopathological variation in keratoconus. Cornea. 1992 Nov;11(6):553-9. PubMed PMID: 1468218.

- ↑ Tsubota K, Mashima Y, Murata H, Sato N, Ogata T. Corneal epithelium in keratoconus. Cornea. 1995 Jan;14(1):77-83. PubMed PMID: 7712741.

- ↑ Kanai A, Kaufman HE. Electron microscopic studies of corneal stroma: aging changes of collagen fibers. Ann Ophthalmol. 1973 Mar;5(3):285-7 passim. PubMed PMID: 4694913.

- ↑ Sawaguchi S, Fukuchi T, Abe H, Kaiya T, Sugar J, Yue BY. Three-dimensional scanning electron microscopic study of keratoconus corneas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998 Jan;116(1):62-8. PubMed PMID: 9445209.

- ↑ Iwamoto T, DeVoe AG. Electron microscopical study of the Fleisher ring. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976 Sep;94(9):1579-84. PubMed PMID: 962667.

- ↑ Shapiro MB, Rodrigues MM, Mandel MR, Krachmer JH. Anterior clear spaces in keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 1986 Oct;93(10):1316-9. PubMed PMID: 3785890.

- ↑ Perry HD, Buxton JN, Fine BS. Round and oval cones in keratoconus. Ophthalmology. 1980 Sep;87(9):905-9. PubMed PMID: 7413154.

- ↑ Kaas-Hansen M. The histopathological changes of keratoconus. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1993 Jun;71(3):411-4. PubMed PMID: 8362646.

- ↑ Pouliquen Y, Graf B, Hamada R, Giraud JP, Offret G. [Fibrocytes in keratoconus. Morphological aspect and modification of the extra-cellular space. Study with light and electron microscopy]. Arch Ophtalmol Rev Gen Ophtalmol. 1972 Aug-Sep;32(8):571-86. French. PubMed PMID: 4267199.

- ↑ Jump up to: 37.0 37.1 Krachmer, J. (2005). Non inflamatory ectatic disorders. In Cornea (2.nd ed., Vol. 2, p. 960). St. Louis [u.a.: Mosby.

- ↑ Pouliquen Y, Graf B, Hamada R, Giraud JP, Offret G. [Fibrocytes in keratoconus. Morphological aspect and modification of the extra-cellular space. Study with light and electron microscopy]. Arch Ophtalmol Rev Gen Ophtalmol. 1972 Aug-Sep;32(8):571-86. French. PubMed PMID: 4267199.

- ↑ Polack FM. Contributions of electron microscopy to the study of corneal pathology. Surv Ophthalmol. 1976 May-Jun;20(6):375-414. Review. PubMed PMID: 779087.

- ↑ Smolek MK. Interlamellar cohesive strength in the vertical meridian of human eye bank corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993 Sep;34(10):2962-9. PubMed PMID: 8360028.

- ↑ Halabis JA. Analysis of the corneal endothelium in keratoconus. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987 Jan;64(1):51-3. PubMed PMID: 3826278.

- ↑ Sturbaum CW, Peiffer RL Jr. Pathology of corneal endothelium in keratoconus. Ophthalmologica. 1993;206(4):192-208. PubMed PMID: 8278166.

- ↑ Jump up to: 43.0 43.1 Rabinowitz, YS. Videokeratographic indices to aid in screening for keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 1995;11: 371–379

- ↑ Maeda, N, Klyce, SD, Smolek, MK, and Thompson, HW. Automated keratoconus screening with corneal topography analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35: 2749–2757

- ↑ Jump up to: 45.0 45.1 Maeda, N, Klyce, SD, and Smolek, MK. Comparison of methods for detecting keratoconus using videokeratography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995; 113: 870–874

- ↑ Amsler, M. Le keratocone fruste au javal. Ophthalmologica. 1938; 96: 77–83

- ↑ Levene, JR. An evaluation of the handheld keratoscope as a diagnostic instrument for corneal astigmatism. Br J Physiol Opt. 1962; 19: 237–251

- ↑ Donaldson, DD. A new instrument for keratography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972; 88: 425–428

- ↑ Rowsey, JJ, Reynolds, AE, and Brown, R. Corneal topography. Corneascope. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981; 99: 1093–1100

- ↑ Jump up to: 50.0 50.1 50.2 Krachmer, JH, Feder, RS, and Belin, MW. Keratoconus and related noninflammatory corneal thinning disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984; 28: 293–322

- ↑ Klyce, SD. Computer-assisted corneal topography. High resolution graphic presentation and analysis of keratoscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984; 25: 1426–1435

- ↑ Jump up to: 52.0 52.1 Belin MW, Ambrósio R. Scheimpflug imaging for keratoconus and ectatic disease. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2013;61(8):401-406. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.116059.

- ↑ Kim SW, Sun HJ, Chang JH, Kim EK, Anterior segment measurements using Pentacam and Orbscan II 1 to 5 years after refractive surgery. J Refract Surg. 2009 Dec; 25(12):1091-7.

- ↑ Yazici AT, Bozkurt E, Alagoz C, Alagoz N, Pekel G, Kaya V, Yilmaz OF, Central corneal thickness, anterior chamber depth, and pupil diameter measurements using Visante OCT, Orbscan, and Pentacam. J Refract Surg. 2010 Feb; 26(2):127-33.

- ↑ Belin MW, Khachikian SS. Corneal diagnosis and evaluation with the OCULUS pentacam. Highlights Ophthalmol. 2007;35:5–7.

- ↑ Maguire LJ, Meyer RF: Ectatic corneal degenerations, in Kaufman H (ed): The Cornea. 1988, pp 485–510

- ↑ Fleischer, B (1906). «Über Keratokonus und eigenartige Pigmentbildung in der Kornea». Münchener medizinische Wochenschrift, 53, s. 625–626.

- ↑ Kriszt A, Losonczy G, Berta A, Takcas L. Presence of Fleischer ring and prominent corneal nerves in keratoconus relatives and normal controls. 2015;8(5):922-927

- ↑ Zadnik K, Barr JT, Gordon MO, Edrington TB. Biomicroscopic signs and disease severity in keratoconus. Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study Group. 1996;15(2):139-146

- ↑ Nesburn AB, Bahri S, Salz J, et al: Keratoconus detected by videokeratography in candidates for photorefractive keratectomy. J Refract Surg 11:194–201, 1995

- ↑ Wilson SE, Klyce SD: Screening for corneal topographic abnormalities before refractive surgery. Ophthalmology 101:147–152, 1994

- ↑ Jump up to: 62.0 62.1 Rabinowitz, Yaron S. Keratoconus. Survey of Ophthalmology, Volume 42, Issue 4, 297 - 319

- ↑ Gimbel HV, Iskander NG, Peters NT, Penno EA. Prevention and Management of Microkeratome-related Laser in situ Keratomileusis Complications. J Refract Surg. 2000 Mar 2;16(2 Suppl):S226-9. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20000302-05. PubMed PMID: 24364840.

- ↑ Rabinowitz YS, Wilson SE, Klyce SD (eds): Corneal Topography: Interpreting Videokeratography. New York, Tokyo, Ig- aku Shoin, 1993

- ↑ Chan AT, Ulate R, Goldich Y, Rootman DS, Chan CC. Terrien Marginal Degeneration: Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Nov;160(5):867-872.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.07.031. Epub 2015 Jul 23. PubMed PMID: 26210866.

- ↑ Baillif S, Garweg JG, Grange JD, Burillon C, Kodjikian L. [Keratoglobus: review of the literature]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2005 Dec;28(10):1145-9. Review. French. PubMed PMID: 16395211.

- ↑ Asbell, P., & Petratos, T. (2015, August 28). Keratoconus (L. Rose, Ed.). Retrieved December 26, 2015, from http://eyewiki.org/Keratoconus