Frontocutaneous Fistula: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

|Additional contributors=Annie Moreau, Andrew Osborn | |Additional contributors=Annie Moreau, Andrew Osborn | ||

|Category=Oculoplastics/Orbit | |Category=Oculoplastics/Orbit | ||

|Date reviewed= | |Assigned editor=Joseph.Giacometti | ||

|Reviewer=Joseph.Giacometti | |||

|Date reviewed=January 21, 2025 | |||

|Article status=Up to Date | |||

}} | }} | ||

= Disease Entity = | = Disease Entity = | ||

| Line 11: | Line 14: | ||

== Disease == | == Disease == | ||

Frontocutaneous fistulas represent an abnormal communication between the frontal sinus and overlying skin as a result of frontal bone erosion, which may be caused by an enlarging frontal sinus mucocele or by chronic frontal sinusitis.<ref name=":0">Rossman D, Verity DH, Lund VJ, Rose GE. Eyelid Fistula: A Feature of Occult Sinus Disease. Orbit. 2007;26(3):159-163. doi:10.1080/01676830701519424</ref> Of note, frontal sinusitis accompanied by subperiosteal abscess and frontal bone osteomyelitis is known as Pott’s puffy tumor.<ref>Appiah-Thompson P, Ngyedu E, Konney A, Appiah-Thompson B. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Frontal Sinusitis. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;15(3):1-5. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2016/25084</ref> Prior bony trauma involving the anterior wall or floor of the frontal sinus may also lead to the development of a frontocutaneous fistula. The anterior wall and floor of the frontal sinus provide paths of least resistance for infection, thus erosion of the frontal bone with a fistula tract may present subcutaneously in the superomedial orbital area or upper eyelid.<ref>Min HJ, Kim KS. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Pott’s Puffy Tumor. ''Ear Nose Throat J''. 2020;99(9):NP101-NP102. doi:10.1177/0145561319856858</ref> Non-cutaneous fistulas with intracranial extension into the anterior fossa may also develop through direct posterior erosion of the outer or inner frontal table, conferring high morbidity and mortality. | |||

== Anatomy == | == Anatomy == | ||

| Line 17: | Line 20: | ||

== Etiology == | == Etiology == | ||

Only a handful of cases of | Only a handful of cases of sinocutaneous fistula secondary to frontal sinus disease have been reported.<ref name=":0" /><ref>Terui H, Numata I, Takata Y, Ogura M, Aiba S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. ''JAMA Dermatol''. 2015;151(11):1261. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0874</ref> Development of Pott's puffy tumor is rare today but was a common phenomenon prior to antibiotic therapy.<ref>Goldfarb A, Hocwald E, Gross M, Eliashar R. Frontal Sinus Cutaneous Fistula: A Complication of Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):490-491. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2003.10.006</ref> First described by Sir Percival Pott in 1760, Pott’s puffy tumor is a subperiosteal abscess associated with underlying osteomyelitis.<ref>Tattersall R, Tattersall R. Pott’s puffy tumour. The Lancet. 2002;359(9311):1060-1063. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08098-4</ref> Chronic frontal sinusitis is the most common cause. In cases of frontal sinusitis related mucoceles, it is theorized that interleukin -1 (IL-1) released from sinus epithelium induces frontal bone erosion.<ref>Lund VJ, Henderson B, Song Y. Involvement of Cytokines and Vascular Adhesion Receptors in the Pathology of Fronto-ethmoidal Mucocoeles. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1993;113(4):540-546. doi:10.3109/00016489309135860</ref> Case reports of subcutaneous fistulas that developed after intranasal methamphetamine use,<ref>Banooni P. Pott Puffy Tumor Associated With Intranasal Methamphetamine. JAMA. 2000;283(10):1293. doi:10.1001/jama.283.10.1287</ref> prior head trauma or craniotomy, hair transplantation,<ref>Koch SE. Pott’s Puffy Tumor A Clinical Marker for Osteomyelitis of the Skull. ''Arch Dermatol''. 1985;121(4):548. doi:10.1001/archderm.1985.01660040132029</ref> and ethmoid<ref>Bağdatoğlu C, Güleryüz A, Ersöz G, Talas DÜ, Kandemir Ö, Köksel T. A Rare Clinical Entity: Pott’s Puffy Tumor. ''Pediatr Neurosurg''. 2001;34(3):156-158. doi:10.1159/000056011</ref> or maxillary sinusitis<ref>Maheshwar, Harris, Al-Mokhthar, Evans. Pott’s puffy tumour: an unusual presentation and management. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115(6):497-499. doi:10.1258/0022215011908036</ref> have also been reported. | ||

Frontocutaneous fistulas most commonly harbor Streptococcal, Staphylococcal, or oral anaerobic infections, although polymicrobial infections may occur. Anaerobes are seen more often in cases with intracranial spread. Adolescents are more typically affected due to the pneumatization process and peak vascularity of the diplopic circulation.<ref>Palabiyik FB, Yazici Z, Cetin B, Celebi S, Hacimustafaoglu M. Pott Puffy Tumor in Children: A Rare Emergency Clinical Entity. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(3):e313-e316. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000002573</ref> However, in a case series of subcutaneous fistulas with orbital involvement, the mean age was 55 years with male predominance.<ref name=":1">Tailor R, Obi E, Burns J, Sampath R, Durrani OM, Ford R. Fronto-orbital mucocele and orbital involvement in occult obstructive frontal sinus disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(4):525-530. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306940</ref> In another case series the mean age was 68 years with equal incidence between genders.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

== Signs and Symptoms == | == Signs and Symptoms == | ||

The clinical presentation of frontocutaneous fistulas can be highly variable. Acute infection may produce more concerning signs and symptoms; patients may present with headache, fever, forehead swelling, nasal drainage, and frontal sinus tenderness. Although Pott’s puffy tumor is known to present with fullness in the forehead, this may not always be seen.<ref name=":2">Wu VF, Smith TL, Poetker DM. Sinocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Chronic Frontal Rhinosinusitis: Case Series and Literature Review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(10):759-763. doi:10.1177/000348940811701010</ref> An acutely progressive headache, neurologic changes, and signs of increased intracranial pressure are concerning for intracranial extension. Cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, and intracranial abscess may occur. Invasive infection can also progress to systemic sepsis.<ref name=":3">Shin JW, Choi IG, Jung SN, Kwon H, Shon WI, Moon SH. Pott Puffy Tumor Appearing With a Frontocutaneous Fistula: ''J Craniofac Surg''. 2012;23(2):e158-e160. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdcc0</ref> | |||

The ophthalmic presentation is also varied depending upon the orbital extent of the fistula. Patients may describe a history of recurrent upper lid erythema and edema over several weeks to months. Eyelid swelling and erythema may more commonly involve the medial canthal region.<ref name=":2" /> Hypotropia may be present along with vertical diplopia. Patients may also have ptosis or proptosis with restriction in upgaze. Pre-septal and orbital cellulitis, orbital abscess or subperiosteal abscess, and optic neuritis have all been associated with chronic frontal sinusitis.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

= Diagnosis = | = Diagnosis = | ||

== Diagnostic procedures == | == Diagnostic procedures == | ||

Brain and sinus Computed Tomography (CT) with contrast must be emergently performed in a patient suspected to have a frontocutaneous fistula. CT provides excellent resolution of the retro-orbital tissues, globe, and sinuses to assess for bony changes. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) should be completed if there is any indication on history, exam, or CT findings of neurologic or intraorbital involvement. Severe bilateral frontal osteoneogenesis is typical in this disease and suggests chronic frontal sinus disease. Air fluid levels may be seen in the frontal sinus. All imaging should be carefully evaluated for subdural, epidural, or intracerebral abscesses. | Brain and sinus Computed Tomography (CT) with contrast must be emergently performed in a patient suspected to have a frontocutaneous fistula. CT provides excellent resolution of the retro-orbital tissues, globe, and sinuses to assess for bony changes. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) should be completed if there is any indication on history, exam, or CT findings of neurologic or intraorbital involvement. Severe bilateral frontal osteoneogenesis is typical in this disease and suggests chronic frontal sinus disease. Air fluid levels may be seen in the frontal sinus. All imaging studies should be carefully evaluated for subdural, epidural, or intracerebral abscesses. Cavernous sinus thrombosis may also be present. A frontocutaneous fistula can be seen as a frontal bone window defect extending into the orbital area. Care should also be taken to also evaluate any bony defects involving the posterior or inner frontal table for intracranial extension. | ||

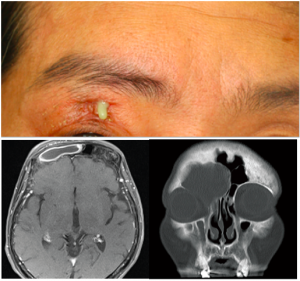

[[File:Screen Shot 2021-11-23 at 7.57.17 PM.png|thumb|A patient with a right frontocutaneous fistula (left), and corresponding CT face showing right frontal sinus wall defect.<ref>Appiah-Thompson P, Ngyedu E, Konney A, Appiah-Thompson B. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Frontal Sinusitis. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;15(3):1-5. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2016/25084<!-- image adapted from original article --></ref><!-- image adapted from original article -->|alt=]][[File:Figure2 fistula.png|thumb|A patient with a right frontocutaneous fistula (top) and corresponding contrast enhanced MRI brain demonstrating a right frontal abscess (bottom left) and CT face demonstrating expanded right frontal sinus with bony defect.<ref>Terui H, Numata I, Takata Y, Ogura M, Aiba S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1261. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0874</ref><!-- image adapted from original article -->|alt=]] | [[File:Screen Shot 2021-11-23 at 7.57.17 PM.png|thumb|A patient with a right frontocutaneous fistula (left), and corresponding CT face showing right frontal sinus wall defect.<ref>Appiah-Thompson P, Ngyedu E, Konney A, Appiah-Thompson B. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Frontal Sinusitis. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;15(3):1-5. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2016/25084<!-- image adapted from original article --></ref><!-- image adapted from original article -->|alt=]][[File:Figure2 fistula.png|thumb|A patient with a right frontocutaneous fistula (top) and corresponding contrast enhanced MRI brain demonstrating a right frontal abscess (bottom left) and CT face demonstrating expanded right frontal sinus with bony defect.<ref>Terui H, Numata I, Takata Y, Ogura M, Aiba S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1261. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0874</ref><!-- image adapted from original article -->|alt=]] | ||

== Differential diagnosis == | == Differential diagnosis == | ||

Eyelid abscess, orbital fat prolapse, dermoid cyst, fungal infection, sino-nasal malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis. | Eyelid abscess, orbital fat prolapse, dermoid cyst, fungal infection, and sino-nasal malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis. | ||

= Management = | = Management = | ||

| Line 38: | Line 41: | ||

= General treatment = | = General treatment = | ||

Diagnosis of frontocutaneous fistula warrants | Diagnosis of frontocutaneous fistula warrants hospital admission for surgical management and intravenous antibiotics. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated and then narrowed based on culture results. A prolonged course of IV antibiotics for 6-8 weeks is required. Steroid therapy with taper may also be considered. Supportive therapies such as IV hydration, saline nasal spray, nasal corticosteroids, and analgesia can be given. | ||

== Consultations == | == Consultations == | ||

Early consultation of ENT specialists for evaluation of surgical intervention is important in mitigating significant morbidity and mortality. Neurosurgery consultation is warranted if there is concern of impending intracranial involvement. | Early consultation of ENT specialists for evaluation of surgical intervention is important in mitigating significant morbidity and mortality. Neurosurgery consultation is warranted if there is concern of impending intracranial involvement. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 47: | ||

== Surgery == | == Surgery == | ||

The goal of surgery is to restore long term patency of the frontal sinus outflow tract, excise the fistula tract, drain all associated abscesses, obtain samples for culture | The goal of surgery is to restore long term patency of the frontal sinus outflow tract, excise the fistula tract, drain all associated abscesses, obtain samples for gram stain and culture, and remove any osteomyelitic bone. Endoscopic sinus surgery remains the gold standard for treatment of chronic sinusitis. The frontal sinus drainage pathway may also be opened via an endoscopic frontal sinusotomy with or without frontal sinus trephination.<ref name=":2" /> A silicone frontal sinus stent can be placed at time of surgery to assist with drainage. Aggressive debridement and evacuation of either sinus, subperiosteal, or intracranial abscess may be done. Depending on the depth of infected frontal bone, craniectomy with bony reconstruction can be considered to prevent recurrence and delayed mucocele formation. Induration of subcutaneous tissues around the ostium of the fistula may mimic malignancy, thus biopsy can be considered in some cases. | ||

== Follow up == | == Follow up == | ||

Follow up imaging is recommended to ensure disease does not recur and MRI is often preferred. Clinical course may be variable. Some authors report symptom recurrence weeks after treatment and may | Follow up imaging is recommended to ensure disease does not recur and MRI is often preferred. Clinical course may be variable. Some authors report symptom recurrence weeks after treatment and may even occur up to six months to one year after surgery.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":3" /> | ||

= Prognosis = | = Prognosis = | ||

Prognosis depends on early detection and treatment. Ophthalmic presentations of eyelid swelling and orbital signs may not obviously point to an underlying sinus pathology and delayed diagnosis may easily lead to inappropriate management. One study found that 47% of ophthalmologists misdiagnosed a | Prognosis depends on early detection and treatment. Ophthalmic presentations of eyelid swelling and orbital signs may not obviously point to an underlying sinus pathology and delayed diagnosis may easily lead to inappropriate management. One study found that 47% of ophthalmologists misdiagnosed a frontal sinus mucocele leading to orbital disease and that average time to correct diagnosis averaged 53 weeks.<ref name=":2" /> This suggests an under- recognition of non-ophthalmologic causes of eyelid swelling, such as sinus disease. Thus rapid recognition, imaging, and treatment of this rare but important clinical entity are crucial to preserving vision and avoiding significant neurologic complications, morbidity, or mortality. | ||

= References = | = References = | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:48, January 21, 2025

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Frontocutaneous fistulas can be recognized by the following code as per the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) nomenclature: H05.89 Other disorders of orbit, L98.8 Other specified disorders of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, M86.8X8 Other Osteomyelitis, other site

Disease

Frontocutaneous fistulas represent an abnormal communication between the frontal sinus and overlying skin as a result of frontal bone erosion, which may be caused by an enlarging frontal sinus mucocele or by chronic frontal sinusitis.[1] Of note, frontal sinusitis accompanied by subperiosteal abscess and frontal bone osteomyelitis is known as Pott’s puffy tumor.[2] Prior bony trauma involving the anterior wall or floor of the frontal sinus may also lead to the development of a frontocutaneous fistula. The anterior wall and floor of the frontal sinus provide paths of least resistance for infection, thus erosion of the frontal bone with a fistula tract may present subcutaneously in the superomedial orbital area or upper eyelid.[3] Non-cutaneous fistulas with intracranial extension into the anterior fossa may also develop through direct posterior erosion of the outer or inner frontal table, conferring high morbidity and mortality.

Anatomy

The frontal sinus is normally drained through the frontonasal duct through the frontal recess.[4] Blockage at this recess can lead to stagnant collection of nasal secretions, creating a nidus for infection. The frontal bone drains via valveless diploic veins which are in open communication with the periosteum and dura mater.[5]

Etiology

Only a handful of cases of sinocutaneous fistula secondary to frontal sinus disease have been reported.[1][6] Development of Pott's puffy tumor is rare today but was a common phenomenon prior to antibiotic therapy.[7] First described by Sir Percival Pott in 1760, Pott’s puffy tumor is a subperiosteal abscess associated with underlying osteomyelitis.[8] Chronic frontal sinusitis is the most common cause. In cases of frontal sinusitis related mucoceles, it is theorized that interleukin -1 (IL-1) released from sinus epithelium induces frontal bone erosion.[9] Case reports of subcutaneous fistulas that developed after intranasal methamphetamine use,[10] prior head trauma or craniotomy, hair transplantation,[11] and ethmoid[12] or maxillary sinusitis[13] have also been reported.

Frontocutaneous fistulas most commonly harbor Streptococcal, Staphylococcal, or oral anaerobic infections, although polymicrobial infections may occur. Anaerobes are seen more often in cases with intracranial spread. Adolescents are more typically affected due to the pneumatization process and peak vascularity of the diplopic circulation.[14] However, in a case series of subcutaneous fistulas with orbital involvement, the mean age was 55 years with male predominance.[15] In another case series the mean age was 68 years with equal incidence between genders.[1]

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical presentation of frontocutaneous fistulas can be highly variable. Acute infection may produce more concerning signs and symptoms; patients may present with headache, fever, forehead swelling, nasal drainage, and frontal sinus tenderness. Although Pott’s puffy tumor is known to present with fullness in the forehead, this may not always be seen.[16] An acutely progressive headache, neurologic changes, and signs of increased intracranial pressure are concerning for intracranial extension. Cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, and intracranial abscess may occur. Invasive infection can also progress to systemic sepsis.[17]

The ophthalmic presentation is also varied depending upon the orbital extent of the fistula. Patients may describe a history of recurrent upper lid erythema and edema over several weeks to months. Eyelid swelling and erythema may more commonly involve the medial canthal region.[16] Hypotropia may be present along with vertical diplopia. Patients may also have ptosis or proptosis with restriction in upgaze. Pre-septal and orbital cellulitis, orbital abscess or subperiosteal abscess, and optic neuritis have all been associated with chronic frontal sinusitis.[15]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic procedures

Brain and sinus Computed Tomography (CT) with contrast must be emergently performed in a patient suspected to have a frontocutaneous fistula. CT provides excellent resolution of the retro-orbital tissues, globe, and sinuses to assess for bony changes. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) should be completed if there is any indication on history, exam, or CT findings of neurologic or intraorbital involvement. Severe bilateral frontal osteoneogenesis is typical in this disease and suggests chronic frontal sinus disease. Air fluid levels may be seen in the frontal sinus. All imaging studies should be carefully evaluated for subdural, epidural, or intracerebral abscesses. Cavernous sinus thrombosis may also be present. A frontocutaneous fistula can be seen as a frontal bone window defect extending into the orbital area. Care should also be taken to also evaluate any bony defects involving the posterior or inner frontal table for intracranial extension.

Differential diagnosis

Eyelid abscess, orbital fat prolapse, dermoid cyst, fungal infection, and sino-nasal malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Management

General treatment

Diagnosis of frontocutaneous fistula warrants hospital admission for surgical management and intravenous antibiotics. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated and then narrowed based on culture results. A prolonged course of IV antibiotics for 6-8 weeks is required. Steroid therapy with taper may also be considered. Supportive therapies such as IV hydration, saline nasal spray, nasal corticosteroids, and analgesia can be given.

Consultations

Early consultation of ENT specialists for evaluation of surgical intervention is important in mitigating significant morbidity and mortality. Neurosurgery consultation is warranted if there is concern of impending intracranial involvement.

Surgery

The goal of surgery is to restore long term patency of the frontal sinus outflow tract, excise the fistula tract, drain all associated abscesses, obtain samples for gram stain and culture, and remove any osteomyelitic bone. Endoscopic sinus surgery remains the gold standard for treatment of chronic sinusitis. The frontal sinus drainage pathway may also be opened via an endoscopic frontal sinusotomy with or without frontal sinus trephination.[16] A silicone frontal sinus stent can be placed at time of surgery to assist with drainage. Aggressive debridement and evacuation of either sinus, subperiosteal, or intracranial abscess may be done. Depending on the depth of infected frontal bone, craniectomy with bony reconstruction can be considered to prevent recurrence and delayed mucocele formation. Induration of subcutaneous tissues around the ostium of the fistula may mimic malignancy, thus biopsy can be considered in some cases.

Follow up

Follow up imaging is recommended to ensure disease does not recur and MRI is often preferred. Clinical course may be variable. Some authors report symptom recurrence weeks after treatment and may even occur up to six months to one year after surgery.[1][17]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on early detection and treatment. Ophthalmic presentations of eyelid swelling and orbital signs may not obviously point to an underlying sinus pathology and delayed diagnosis may easily lead to inappropriate management. One study found that 47% of ophthalmologists misdiagnosed a frontal sinus mucocele leading to orbital disease and that average time to correct diagnosis averaged 53 weeks.[16] This suggests an under- recognition of non-ophthalmologic causes of eyelid swelling, such as sinus disease. Thus rapid recognition, imaging, and treatment of this rare but important clinical entity are crucial to preserving vision and avoiding significant neurologic complications, morbidity, or mortality.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rossman D, Verity DH, Lund VJ, Rose GE. Eyelid Fistula: A Feature of Occult Sinus Disease. Orbit. 2007;26(3):159-163. doi:10.1080/01676830701519424

- ↑ Appiah-Thompson P, Ngyedu E, Konney A, Appiah-Thompson B. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Frontal Sinusitis. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;15(3):1-5. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2016/25084

- ↑ Min HJ, Kim KS. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020;99(9):NP101-NP102. doi:10.1177/0145561319856858

- ↑ Daniels DL, Mafee MF, Smith MM, et al. The frontal sinus drainage pathway and related structures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(8):1618-1627.

- ↑ Davidson L, McComb JG. Epidural–cutaneous fistula in association with the Pott puffy tumor in an adolescent: Case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2006;105(3):235-237. doi:10.3171/ped.2006.105.3.235

- ↑ Terui H, Numata I, Takata Y, Ogura M, Aiba S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1261. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0874

- ↑ Goldfarb A, Hocwald E, Gross M, Eliashar R. Frontal Sinus Cutaneous Fistula: A Complication of Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2004;130(4):490-491. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2003.10.006

- ↑ Tattersall R, Tattersall R. Pott’s puffy tumour. The Lancet. 2002;359(9311):1060-1063. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08098-4

- ↑ Lund VJ, Henderson B, Song Y. Involvement of Cytokines and Vascular Adhesion Receptors in the Pathology of Fronto-ethmoidal Mucocoeles. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh). 1993;113(4):540-546. doi:10.3109/00016489309135860

- ↑ Banooni P. Pott Puffy Tumor Associated With Intranasal Methamphetamine. JAMA. 2000;283(10):1293. doi:10.1001/jama.283.10.1287

- ↑ Koch SE. Pott’s Puffy Tumor A Clinical Marker for Osteomyelitis of the Skull. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(4):548. doi:10.1001/archderm.1985.01660040132029

- ↑ Bağdatoğlu C, Güleryüz A, Ersöz G, Talas DÜ, Kandemir Ö, Köksel T. A Rare Clinical Entity: Pott’s Puffy Tumor. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;34(3):156-158. doi:10.1159/000056011

- ↑ Maheshwar, Harris, Al-Mokhthar, Evans. Pott’s puffy tumour: an unusual presentation and management. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115(6):497-499. doi:10.1258/0022215011908036

- ↑ Palabiyik FB, Yazici Z, Cetin B, Celebi S, Hacimustafaoglu M. Pott Puffy Tumor in Children: A Rare Emergency Clinical Entity. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(3):e313-e316. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000002573

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Tailor R, Obi E, Burns J, Sampath R, Durrani OM, Ford R. Fronto-orbital mucocele and orbital involvement in occult obstructive frontal sinus disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(4):525-530. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306940

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Wu VF, Smith TL, Poetker DM. Sinocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Chronic Frontal Rhinosinusitis: Case Series and Literature Review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(10):759-763. doi:10.1177/000348940811701010

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Shin JW, Choi IG, Jung SN, Kwon H, Shon WI, Moon SH. Pott Puffy Tumor Appearing With a Frontocutaneous Fistula: J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(2):e158-e160. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cdcc0

- ↑ Appiah-Thompson P, Ngyedu E, Konney A, Appiah-Thompson B. Frontocutaneous Fistula Secondary to Frontal Sinusitis. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;15(3):1-5. doi:10.9734/BJMMR/2016/25084

- ↑ Terui H, Numata I, Takata Y, Ogura M, Aiba S. Pott’s Puffy Tumor Caused by Chronic Sinusitis Resulting in Sinocutaneous Fistula. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1261. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.0874