Vitreopapillary Traction Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Vitreopapillary traction (VPT) syndrome is characterized by incomplete vitreous separation with persistent vitreous attachment to the peripapillary region. The tractional forces from the vitreous cortex may lead to morphologic disturbance of the attached structures, resulting in visual disturbances.

Pathophysiology

The vitreous humor is comprised of a meshwork of collagen fibrils with hyaluronic acid, forming a gel structure to fill the center of the eye.[1] With aging of the vitreous, there is breakdown of collagen fibrils and loss of proteoglycans, resulting in liquefaction of the gel structure[2] and the development of fluid-filled pockets, typically beginning in the front of the macula and in the central vitreous cavity.[3]

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is defined as a separation between the posterior vitreous cortex and the inner limiting membrane of the retina and is typically innocuous.[1] Evolution of PVD has been described by an optical coherence tomography (OCT) study by Johnson in 2010. He explains that PVD typically begins at the perifoveal macula, progresses to the peripheral retina and the optic disc is usually the final point of attachment.[3] Depending on the stage of PVD, incomplete separation between the vitreous cortex and retina, in conjunction with large movements of the vitreous gel during ocular movements can result in additional tractional forces. Both static and dynamic tractional forces can cause visual symptoms and anatomic signs, though dynamic forces are likely play a greater role.[3][4] The site of adhesion is variable, and depending on the location, may cause retinal hemorrhages, vitreomacular traction, retinal tears, or vitreopapillary traction syndrome.[1][3][5]

In the case of vitreopapillary traction, an observation study of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and optic disc traction proposed that vitreopapillary traction may damage the optic disc via decreased axoplasmic flow in the optic nerve fibers and/or mechanical reduction of perfusion in the posterior ciliary arteries. The effects of each mechanism may be reversible, but in the long term may lead to irreversible damage.[6]

Risk Factors and associations

Because the development of vitreopapillary traction is typically related to PVD, their risk factors are likely similar. These risk factors for PVD include older age, myopia, and prior cataract extraction surgery. In myopic eyes, PVD occurs on average 10 years earlier than emmetropic and hyperopic eyes.[1] In addition to PVD, vitreopapillary traction has been described in association with diabetic retinopathy[6] including diabetic macular edema[7], other macular diseases (macular holes, dry macular degeneration, and macular pucker)[8], epiretinal membrane[9] and central retinal vein occlusion.[10]

Diagnosis

History

Patients with vitreopapillary syndrome can present in most age groups but are typically over the age of 50 and both sexes are equally affected.[6][7][9] Cases of vitreopapillary traction have been described in patients as young as 11 years old.[4] Risk factors include myopia and prior cataract extraction surgery.[11]

Symptoms

The symptoms of vitreopapillary traction syndrome are variable. Some patients are asymptomatic, while others have previously described photopsias, blurry vision, spots, shadows or smudges in the visual field.[4] Gaze-evoked amaurosis attributed to vitreopapillary traction has also been described.[12]

Physical Examination

Examination of patients with vitreopapillary traction syndrome attributed to incomplete PVD typically reveals a best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/25 or greater, mild to no relative afferent pupillary defect, and no dyschromatopsia, though red desaturation has been noted. Ophthalmoscopic examination may reveal incomplete PVD, a small or hypoplastic disc, disc elevation, intrapapillary or peripapillary hemorrhage or focal whitening of the nerve fiber layer.[4][11][12]

Diagnostic testing

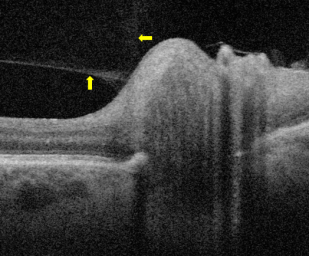

Optical coherence tomography

The presence of vitreopapillary traction was historically assessed by ophthalmoscopy and dilated slit lamp microscopy. Advanced non-invasive imaging techniques such as OCT have allowed for better morphologic characterization of the posterior hyaloid, retina and vitreopapillary interface. In vitreopapillary adhesion and traction, OCT findings may include optic disc elevation, retinal nerve fiber layer thickening, PVD with a thickened, hyperreflective posterior hyaloid attached to the optic disc or optic disc margin.[3][11][13]

Ultrasonography

Orbital ultrasound in vitreopapillary traction may show elevation of the optic nerve head, thickening of the vitreopapillary interface, and/or a partial attachment of the posterior vitreous to the disc or disc margins.[4][12]

Automated perimetry

Visual field testing by automated perimetry have been normal in some patients but others may demonstrate shallow generalized depression, arcuate scotomas, enlarged or blind spots. Contralateral unaffected eyes typically have normal visual field testing.[4][12]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for isolated vitreopapillary traction syndrome can include:

- Papilledema

- Optic disc drusen

Management

Observation

Cases of isolated vitreopapillary traction syndrome attributed to incomplete PVD have typically been managed conservatively by observation. In the first case series by Katz and Hoyt, the intrapapillary and peripapillary hemorrhages had resolved without any sequela or visual impairment at 6-month follow-up.[4] In their second case series of gaze-evoked amaurosis, the described visual disturbances and visual field defects resolved over a period of weeks to months.[12]

Surgical Intervention

Pars planar vitrectomy (PPV) is the most common surgical intervention performed for vitreopapillary traction release. Surgical release by PPV for patients with vitreopapillary traction due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy has demonstrated improvement in BCVA and visual evoked potentials.[6][14] A case report of isolated vitreopapillary traction showed improvement in BCVA from 20/80 to 20/25 after PPV.[15]

In the case of a 16-year-old patient with progressive vision loss for 6 years due to vitreopapillary traction, only a modest recovery was observed following PPV. Surgical release reestablished normal anatomical structure and resulted in a modest improvement in the visual field defect, but the BCVA remained unchanged at 20/300.[16]

Medical Management

There are no approved pharmacologic therapies for vitreopapillary traction. However, agents targeting the vitreoretinal interface such as ocriplasmin, a recombinant protease with activity against fibronectin and laminin, are being studied in treating vitreomacular traction syndrome. https://eyewiki.org/Vitreomacular_Traction_Syndrome#Medical_therapy

Outcomes

In cases of VPT attributed to incomplete PVD, the visual outcomes are typically 20/25 or better with observation or conservative management.[4][12] Short-term vision changes due to VPT can be reversible, but it has been postulated that long term traction may lead to irreversible optic neuropathy.6 However, the temporal relationship between traction and visual outcome has not been well-studied.

In a Point Counter-Point article by Cameron F. Parsa, MD, Zoë R. Williams, MD, Gregory P. Van Stavern, MD, and Andrew G. Lee, MD, experts debate whether vitreopapillary traction plays a major role in development of NAION.[17]

Additional Resources

Gabriel RS, Boisvert CJ, Mehta MC. Review of Vitreopapillary Traction Syndrome. Neuroophthalmology. 2020 Feb 26;44(4):213-218. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2020.1725063. PMID: 33012906; PMCID: PMC7518309.

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Sebag J. The vitreous : structure, function, and pathobiology. Springer-Verlag; 1989:xi, 173 p : ill. (some col.).

- ↑ Los LI, van der Worp RJ, van Luyn MJ, Hooymans JM. Age-related liquefaction of the human vitreous body: LM and TEM evaluation of the role of proteoglycans and collagen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. Jul 2003;44(7):2828-33. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-0588

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Johnson MW. Posterior vitreous detachment: evolution and complications of its early stages. Am J Ophthalmol. Mar 2010;149(3):371-82.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.022

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Katz B, Hoyt WF. Intrapapillary and peripapillary hemorrhage in young patients with incomplete posterior vitreous detachment. Signs of vitreopapillary traction. Ophthalmology. Feb 1995;102(2):349-54. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31018-4

- ↑ Schepens CL. Clinical aspects of pathologic changes in the vitreous body. Am J Ophthalmol. Jul 1954;38(1:2):8-21. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(54)90004-5

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kroll P, Wiegand W, Schmidt J. Vitreopapillary traction in proliferative diabetic vitreoretinopathy [ssee comments]. Br J Ophthalmol. Mar 1999;83(3):261-4. doi:10.1136/bjo.83.3.261

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Karatas M, Ramirez JA, Ophir A. Diabetic vitreopapillary traction and macular oedema. Eye (Lond). Jun 2005;19(6):676-82. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6701622

- ↑ Sebag J, Wang MY, Nguyen D, Sadun AA. Vitreopapillary adhesion in macular diseases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. Dec 2009;107:35-44.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Kim YW, Jeoung JW, Yu HG. Vitreopapillary Traction in Eyes with Idiopathic Epiretinal Membrane: A Spectral–Domain Optical Coherence Tomography Study. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1976-1982. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.011

- ↑ Rumelt S, Karatas M, Pikkel J, Majlin M, Ophir A. Optic Disc Traction Syndrome Associated With Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2003;121(8):1093-1097. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.8.1093

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 Hedges TR, 3rd, Flattem NL, Bagga A. Vitreopapillary traction confirmed by optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. Feb 2006;124(2):279-81. doi:10.1001/archopht.124.2.279

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Katz B, Hoyt WF. Gaze-evoked amaurosis from vitreopapillary traction. Am J Ophthalmol. Apr 2005;139(4):631-7. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2004.10.045

- ↑ Gabriel RS, Boisvert CJ, Mehta MC. Review of Vitreopapillary Traction Syndrome. Neuroophthalmology. 2020;44(4):213-218. doi:10.1080/01658107.2020.1725063

- ↑ Shukla D, Kolluru CM, Rajendran A, Deshpande N, Kim R. Evolution and management of diabetic tractional papillopathy: an optical coherence tomographic study. Eye. 2007/04/01 2007;21(4):569-571. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702652

- ↑ Meyer CH, Schmidt JC, Mennel S, Kroll P. Functional and anatomical results of vitreopapillary traction after vitrectomy. Acta Ophthalmologica Scandinavica. 2007;85(2):221-222. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00792.x

- ↑ Nagesha CK, Rishi P, Rishi E. Vitrectomy for vitreopapillary traction in a nondiabetic 16-year-old girl. Oman J Ophthalmol. Jan-Apr 2017;10(1):38-39. doi:10.4103/0974-620x.200697

- ↑ Parsa CF, Williams ZR, Van Stavern GP, Lee AG. Does Vitreopapillary Traction Cause Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy? J Neuroophthalmol. Jun 1 2022;42(2):260-271. doi:10.1097/wno.0000000000001464