Uveitic Glaucoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Summary

Uveitic glaucoma is a common complication of uveitis affecting some 20% of patients. The term uveitic glaucoma is used to describe glaucoma resulting indirectly or directly from uveitis. Glaucoma is more commonly associated with anterior uveitis and with chronic forms of uveitis. Uveitis and its treatment can lead to elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). A persistent rise in IOP can lead to glaucamatous optic neuropathy and visual field loss[1]. Intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation in uveitis can be secondary to open angle or angle closure mechanisms. It can also be to due corticosteroid induced glaucoma[2]. The pathogenesis may be acute in onset, with rapid onset inflammation, obstruction of intertrabecular spaces and subsequent increased IOP. The pathogenesis may also be chronic, with repeated bouts of uveitis leading to fibroblastic infiltration and formation of scar tissue that slowly obstructs the anterior chamber angle.

Management of uveitic glaucoma is two pronged. The etiology of uveitis must be idenitifed and treated. Next, the elevated IOP is treated, making sure to assess for steroid-induced ocular hypertension. Medical and surgical therapy can be used to fully treat the uveitis glaucoma.

Background

Joseph Beer is credited with first recognizing the association between uveitis and glaucoma in 1813 and described it as arthritic iritis[3]. Priestly Smith published the first modern classification nearly 70 years later in 1891[4].

Prevalence

The estimated prevalence of glaucoma due to uveitis varies according to source, but is estimated between 10 to 20% of cases, but can be as high as 46% in cases of severe chronic uveitis[5].

Pathophysiology

The mechanism for ocular hypertension in the setting of chronic anterior chamber inflammation is similar in many respects to the pathogenesis believed to underlie primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG). However, in uveitic glaucoma, obstruction of the outflow pathways, comprising the uveal and juxtacannalicular trabecular meshwork structures, follows disruption of the blood aqueous barrier (BAB) due to inflammation rather than due to idiopathic causes as in POAG. This allows inflammatory cells to enter the anterior chamber and disrupt the aqueous outflow equilibrium[6]. These inflammatory cells are capable of physically obstructing the outflow TM, as well as producing cytotoxic agents that can lead to permanent scarring of the TM lamellae and endothelial cells which line Schlemm’s canal[7] [8]. Inflammatory cells are known to act by PGE1- and PGE-2 mediated biochemical pathways which can lead to breakdown of the BAB[9]. This may explain the similarities between uveitic glaucoma and corticosteroid induced glaucoma. Complications may include neovascularization of the anterior chamber angle with hemorrhage and worsening obstruction.

Diagnosis

Symptoms of acute onset uveitis include pain, blurry vision, headache, photophobia, and colored haloes. The following findings may be seen on slit lamp examination: keratic precipiates, band keratopathy (in chronic cases), epithelial dendrites, corneal stromal scarring, iris may show stromal atrophy, nodules, posterior synechiae, and neovascularization. Cell and flare will be noted in the anterior chamber. The lens may show increased pigment on the anterior capsule. The intraocular pressure may be low due to inflammation affecting the ciliary body's aqueous production or it may be high if there is decreased aqueous outflow. On gonioscopy PAS may be present. Fundus examination may show optic nerve damage, cupping, or other signs consistent with glaucoma. Other potential posterior segment findings include: cystoid macular edema, retinitis, perivascular sheathing, choroidal infiltrates, or retinal detachment.

Signs of glaucoma include elevated intraocular pressure, glaucomatous excavation of the optic nerve, retinal nerve fiber layer defects, glaucomatous visual field scotomas, pupillary block, and peripheral anterior synechaie.

Management

Patients presenting with uveitis should be worked up for underlying systemic causes. Assessment for arthritis, infections, mucosa or skin lesions, and cough may lead one to order targeted tests. Uveitides associated with glaucoma include ankylosing spondylitis (order HLA-B27, sacroiliac joint imaging), syphilis (order RPR or VDRL), tuberculosis (order quantiferon gold, PPD, Chest X-ray), sarcoidosis (order angiotensin converting enzyme and chest xray/CT scan). Specific ocular inflammations associated with a high rate of secondary glaucoma that should be considered in cases of uveitic glaucoma: include Fuch’s heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHIC), glaucomatocyclitic crisis or Possner-Schlossman syndrome, sarcoidosis, juvenile rhematoid arthritis (JRA), and herpetic keratouveitis.

Medical Therapy

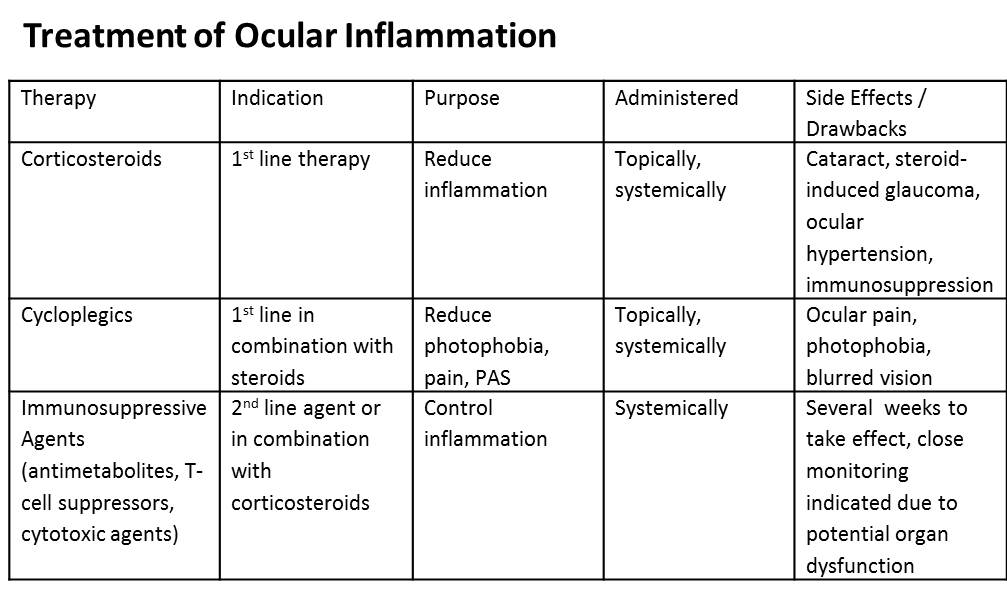

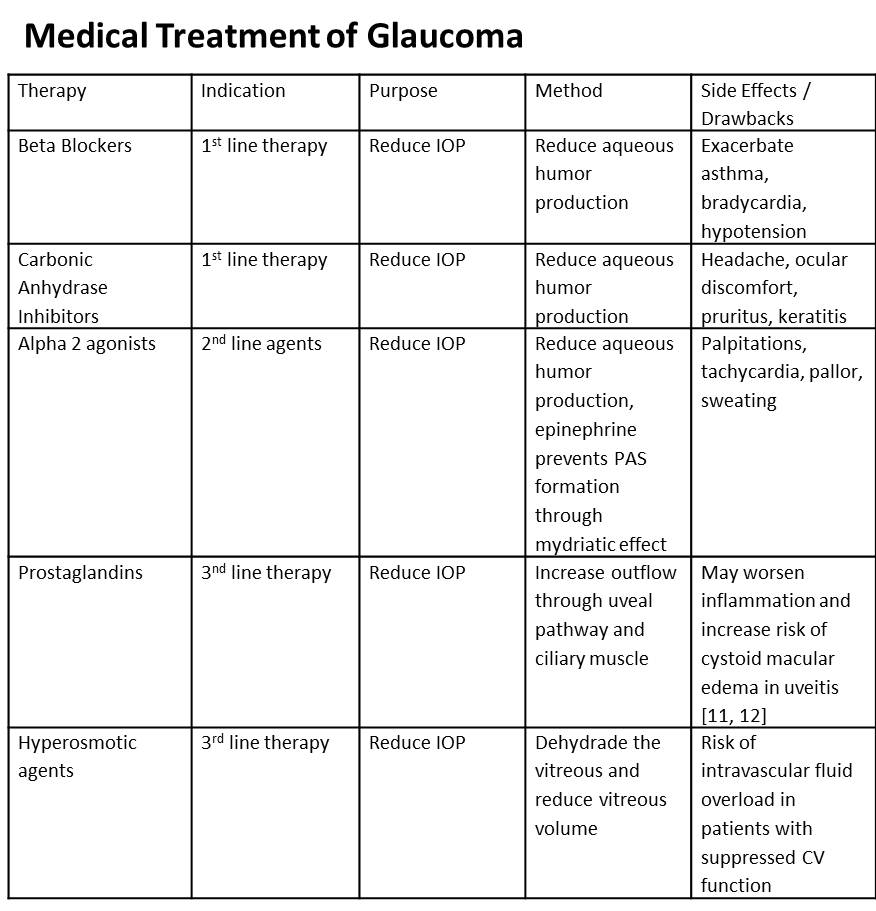

Treatment of uveitic glaucoma depends on the clinical presentation, but ultimately is directed at control of ocular hypertension, treatment of ocular inflammation and diagnosing and treating systemic disease. The major objective is to provide the patient with symptomatic relief, protect the optic nerve from the damaging effects of persistent or acutely elevated IOP, and prevent posterior synechiae formation while reducing the risk of angle closure and subsequent need for surgical therapy. Finally, long term management is aimed and preventing future attacks via repeat uveitis. Medical therapy is utilized first and only in cases refractory to medical management is surgery considered. To control inflammation corticosteroids, cycloplegics, T-cell suppressors, and cytotoxic agents are employed (Table 1). To control ocular hypertension ocular hypotensive agents such as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, prostaglandins, and hyperosmotic agents are used (Table 2). Miotics are generally avoided in uveitic glaucoma since they can further break down the blood-aqeuous barrier.

Table 1

Table 2

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is reserved for refractory cases of uveitic glaucoma unresponsive to maximal medical therapy, as well as for cases of acute angle closure glaucoma. Generally, it is best to avoid surgery during the acute inflammatory phase and always use the least invasive method possible. The surgical procedure of choice is a glaucoma drainage implant if there is active inflammation. Studies have shown that all 3 common types of valves (Ahmed, Baerveldt, and Molteno) are effective in lowering intraocular pressure and reducing the number of glaucoma medications[10]

[11][12][13]. Trabeculectomy with antiproliferative agent can be used in uncontrolled IOP cases, as well. In a retrospective study Ceballos et al[14] reported a success rate of 78% at 1 year and 62% at 2 years. In their study male gender was a risk factor for failure. 51% of phakic patients required cataract surgery. The trabeculectomy can fail postoperatively secondary to intense and persistent inflammation. In a report out of Japan, it was found that trabeculectomy done for uveitic glaucoma in eyes where the uveitis was inactive had a similar success rate to trabeculectomy done in POAG eyes[15]. In concomitant cases of cataract and uncontrolled IOP, phacotrabeculectomy with mitomycin C can be performed with good outcomes[16]. Nonpenetrating filtering surgery has been reported to be successful in surgical management of refractory cases[17] [18]. Goniotomy is an option in pediatric uveitic glaucoma cases[19]. There is no role for cyclophotocoagulation and laser trabeculoplasty in the management of uveitic glaucoma since these procedures are pro-inflammatory.

In secondary angle-closure glaucoma due to pupillary block, laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is usually the treatment of choice, however, the LPI may close secondary to inflammatory membranes with reccurence of the pupillary block. If there is active inflammation, a better treatment is a surgical iridotomy with posterior synechiolysis[20].

References

- ↑ Bodh SA, Kumar V, Raina UK, et al. Inflammatory glaucoma. Oman J Ophthalmol 2011; 4:3-9.

- ↑ Armaly MF. Effect of corticosteroids on intraocular pressure and fluid dynamics. I. The effect of dexamethasone in the normal eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 1963;70:482.

- ↑ Beer GJ. Die Lehre v. d. Augenkrankheiten. Vienna. 1813;1:633.

- ↑ Smith P. The pathology and treatment of glaucoma. London: J and A Churchhill; 1891.

- ↑ Netland PA, Denton NC. Uveitic glaucoma. Contemp Ophthalmol 2006; 5:1-6.

- ↑ Freddo TF, Patterson MM, Scott DR. Influence of mercurial sulfhydryl agents on aqueous outflow pathway in enucleated human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1984; 25:278-85.

- ↑ Roth M, Simmons RJ. Glaucoma associated with precipitates on the trabecular meshwork. Ophthalmology 1979; 86:1613-9.

- ↑ Richardson TM, Hutchinson BT, Grant WM. The outflow tract in pigmentary glaucoma: a light and electron microscopic study. Arch Ophthalmol 1977; 95:1015-25.

- ↑ Chiang TS, Thomas RP. Ocular hypertension following infusion of prostaglandin E1. Arch Ophthalmol 1972; 88:418-20.

- ↑ Papadaki TG, Zacharopoulos IP, Pasquale LR, et al. Long-term results of Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation for uveitic glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 144(1):62-69.

- ↑ Rachmiel R, Trope GE, Buys YM, et al. Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation in uvietic glaucoma versus open-angle glaucoma patients. Can J Ophthalmol 2008; 43(4):462-7.

- ↑ Ceballos EM, Parrish RK, Schiffman JC. Outcome of Baerveldt glaucoma drainage implants for the treatment of uveitic glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2002; 109(12):2256-60.

- ↑ Vuori ML. Molteno aqueous shunt as a primary surgical intervention for uveitic glaucoma:long-term results. Acta Ophthalmol 2010; 88(10);33-36.

- ↑ Ceballos EM, Beck AD, Lynn MJ. Trabeculectomy with antiproliferative agents in uveitic glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2002; 11(3):189-96.

- ↑ Kaburaki T, Koshino T, Kawashima H, et al. Initial trabeculectomy with mitomycin C in eyes with uveitic glaucoma with inactive uveitis. Eye 2009; 23(7):1509-17.

- ↑ Park UC, Ahn JK, Park KH, et al. Phacotrabeculectomy with mitomycin C in patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2006; 142(6):1005-12.

- ↑ Auer C, Mermoud A, Herbort CP. Deep sclerectomy for the management of uncontrolled uveitic glaucoma: preliminary data. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2004; 221(5):339-42.

- ↑ Al Obeidan SA, Osman EA, Al-Muammar AM, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep sclerectomy in uvieitc glaucoma. Int Ophthalmol 2009; 29(5):367-72.

- ↑ Ho CL, Wong EY, Walton DS. Goniosurgery for glaucoma complicating chronic childhood uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122(6):838-844.

- ↑ Kulkarni A, Barton K. Uvieitc Glaucoma in Glaucoma Eds Shaarawy TM, Sherwood MB, Hitchings RA, and Crowston JG. Glaucoma. Vol 1. China: Saunders: 2009:(33)393-407.