Uveal Lymphoma

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Uveal lymphoma, is a subcategory of intraocular lymphoma that predominantly involves the uvea. This article will outline the general features, diagnostic process, and current treatment regimen for this rare disease.

Condition Entity

Uveal lymphoma is a subcategory of intraocular lymphoma. Intraocular lymphoma is categorized according to whether it predominantly involves the retina or the uvea. Uveal tumors can be further classified as primary or secondary. Uveal lymphoma most typically arises from B-cell origin as a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Primary uveal lymphoma can be further classified by its location as choroidal, iridal, or ciliary body lymphoma. Primary choroidal lymphoma accounts for the majority of cases and is most frequently a low-grade lymphoma.[1] Fewer than a dozen cases of primary iridal lymphoma have been reported in the literature[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11], and only one case of primary ciliary body lymphoma has been reported.[12]. Secondary classification occurs with an intraocular manifestation of disseminated disease.

Epidemiology

To date there is limited data on the prevalence of uveal lymphoma given its rare nature. Demographically, it most commonly affects elderly patients with a mean age in the 60-70s. Women are more commonly affected than men at a near 2:1 ratio and to our knowledge there has been no documented affect shown among different races.[13]

Risk Factors

Risk factors for uveal lymphoma are poorly understood and not well documented, as there have only been approximately 80 cases described in the literature.[14]

Signs & Symptoms

Presenting symptoms include:

- Recurrent, painless, episodes of blurred vision

- Metamorphopsia, which is caused by secondary serous retinal detachment due to foveal thickening[15]

Clinical Features

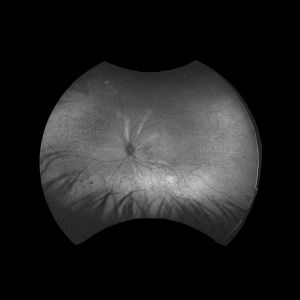

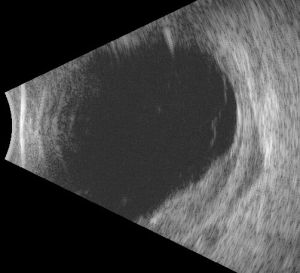

The dominant early sign is multifocal, yellow choroidal swellings on fundus exam. They can resemble multifocal choroiditis or birdshot choroidopathy.[16] Aronow et al. found that of 34 effected eyes, all of them showed yellow-white choroidal infiltrates on ophthalmic examination.[1] Uveal tract thickening can also be seen on fundoscopy, which contributes to the serous retinal detachment often seen.[16] Choroidal folds are common due to the thickened choroid. One hallmark of a choroidal lymphoma is the presence of extra-scleral extension of the choroidal mass, which is often seen with ultrasound imaging. Images 1 and 2 demonstrate choroidal thickening, choroidal folds, and hyper-autofluorescent flecks in the macula in a patient presenting with uveal lymphoma.

Diagnostic Studies

Due to the rarity of disease, there is limited information regarding the typical features of uveal lymphoma. Imaging plays a crucial role in the initial diagnostic process as it allows for the detection of extraocular involvement.

Ancillary imaging can help to understand the extent of the disease. B-scan ultrasonography can reveal extrascleral extension (ESE) with the most common pattern being crescentic thickening outside of the posterior scleral margin. These ESE are often concentrated in the posterior aspect of the globe near the optic nerve, though they can be seen more anteriorly. Aronow et al. found that in 75.9% of cases, B-scan ultrasonography revealed ESE. In their case series, indocyanine green angiography (ICG) also revealed focal regions of hypofluorescence which corresponded to the choroidal infiltrates seen on clinical examination.[1]

Neuroimaging can be performed via magnetic resonance imaging allowing for higher resolution visualization of the soft tissue in order to detect regions of ESE. However, this has shown to be less sensitive than B-scan ultrasonography.[1]

Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis. Vitreous biopsies are obtained through fine needle aspiration, vitreous aspiration, or via pars plana vitrectomy. However, ocular biopsies can prove challenging given the small amount of tissue that can be obtained and the small number of cells on which to base a diagnosis.

Immunocytology can also aid in the diagnosis given that the majority of uveal lymphomas are of B-cell origin, they should express B-cell antigens such as CD20, CD79a or PAX5.[17] Flow cytometry has also shown promise in aiding the diagnosis and helping differentiate between inflammatory and neoplastic uveitis.

Physical Exam

As stated above under ‘Clinical Features’ multifocal yellow choroidal infiltrates are the single most dominant finding on ophthalmic examination. The infiltrates are most commonly anterior to the arcades and in a diffuse or superotemporal distribution.[1]

Imaging Features

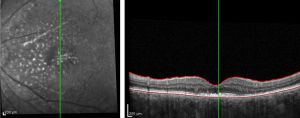

As outlined above in the ‘Diagnostic Studies’ section, evaluation of uveal lymphoma includes ultrasonography, angiography and high resolution neuroimaging. B-scan ultrasonography allows for evaluation of the posterior segment of the eye. Findings are not specific, but can aid in narrowing the differential diagnosis and identifying ESE.[18] OCT imaging can also be beneficial in diagnosis and often reveals a lumpy bumpy choroid as seen in image 4.

Angiography can help to localize the layer that the infiltrates reside and can show hypofluorescent areas due to the blocking effect of sub-RPE masses. If RPE atrophy has occurred, hyperfluorescent areas may be seen.[19] It has been noted that ICG is the preferred form of angiography for uveal lymphoma over fluorescein angiography (FA) as ICG yields more reproducible findings.[1][20]

Neuroimaging can be used to visualize ESE and to detect CNS involvement. It can be performed via CT, MRI and positron emission tomography. MRI is superior to CT in detecting lymphoid lesions in the CNS, however both are limited. Aronow et al. found that CT detected 57.1% of eyes with ESE evident on B-scan ultrasonography while MRI detected 70%.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

A thorough exam and use of the diagnostic studies listed above are important to help differentiate uveal lymphomas from other ocular pathologies. Differential diagnosis of uveal lymphoma is broad and includes:

- Diffuse or amelanotic uveal melanoma

- Uveal effusion syndrome

- Posterior scleritis

- Uveal metastases

- Uveitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Birdshot chorioretinopathy

- Syphilis

- Tuberculosis

- HSV ophthalmicus

Clinical Course

Given the rare nature of primary ciliary body lymphoma and primary iridal lymphoma, there is very little data on their clinical course. However, primary choroidal lymphoma has shown a particularly indolent clinical course. It was previously known as ‘uveal or intraocular pseudotumor’ or ‘reactive lymphoid hyperplasia’ due to its idle nature.[14] It is typically low grade and less aggressive than other forms of lymphoma. A more aggressive form has been documented, but this is very rare.[21]

Treatment Options & Prognosis

The prognosis for primary choroidal lymphoma, the most common subtype of uveal lymphoma, is very good. Given that uveal lymphoma is most frequently low-grade, it has shown to be less aggressive than other forms of lymphoma.[15] Lymphoma cells have been shown to be very sensitive to radiation, making external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) a first-line modality for uveal lymphoma. Coupland et al reported complete remission in patients treated with a median EBRT dose of 3500 cGy.[15] Other reports of uveal lymphoma treated with a median EBRT dose of 3060 cGy achieved complete remission in all patients with localized disease.[1]

Widely accepted treatment algorithms for the disease have not been established due to its rarity. However, Cleveland Clinic has established their own algorithm which is to treat individuals with ocular-only disease with EBRT and those with bilateral or systemic disease with anti-CD20+ agents like rituximab.[1] One report showed that of 3 patients treated with 4 cycles of rituximab therapy, 1 patient achieved stable/asymptomatic disease and 2 patients showed partial remission.[1] To our knowledge, comparative studies pertaining to the treatment of uveal lymphoma with rituximab have not been performed.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Aronow, Mary E., MD, et al. “Uveal Lymphoma: Clinical Features, Diagnostic Studies, Treatment Selection, and Outcomes.” Ophthalmology (Rochester, Minn.), vol. 121, no. 1, 2014, pp. 334–341.

- ↑ Raju VK, Green WR. Reticulum cell sarcoma of the uvea. Ann Ophthalmol 1982; 14: 555–60

- ↑ Velez G, De Smet MD, Whitcup SM, Robinson M, Nussenblatt RB, Chan CC. Iris involvement in primary intraocular lymphoma: report of two cases and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2000; 44: 518–26.

- ↑ Cooper EL, Riker JL. Malignant lymphoma of the uveal tract. Am J Ophthalmol 1951; 34: 1153–8.

- ↑ Corriveau C, Easterbrook M, Payne D. Lymphoma simulating uveitis (masquerade syndrome). Can J Ophthalmol 1986; 21: 144–9.

- ↑ Goldey SH, Stern GA, Oblon DJ, Mendenhall NP, Smith LJ, Duque RE. Immunophenotypic characterization of an unusual T-cell lymphoma presenting as anterior uveitis. A clinicopathologic case report. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107: 1349–53.

- ↑ Jensen OA, Johansen S, Kiss K. Intraocular T-cell lymphoma mimicking a ring melanoma. First manifestation of systemic disease. Report of a case and survey of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1994; 232: 148–52.

- ↑ Lobo A, Larkin G, Clark BJ, Towler HM, Lightman S. Pseudo-hypopyon as the presenting feature in B-cell and T-cell intraocular lymphoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2003; 31: 155–8

- ↑ Yahalom C, Cohen Y, Averbukh E, Anteby I, Amir G, Pe'er J. Bilateral iridociliary T-cell lymphoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 204–7.

- ↑ Yamada K, Hirata A, Kimura A, Tanihara H. A case of primary B-cell type non-Hodgkin lymphoma originating in the iris. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 380–2.

- ↑ Shields JA, Augsburger JJ, Gonder JR, MacLeod D. Localized benign lymphoid tumor of the iris. Arch Ophthalmol 1981; 99: 2147–8.

- ↑ Coupland, Sarah E, and Damato, Bertil. “Understanding Intraocular Lymphomas.” Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, vol. 36, no. 6, 2008, pp. 564–578.

- ↑ Peterson K, Gordon KB, Heinemann MH, DeAngelis LM (1993) The clinical spectrum of ocular lymphoma. Cancer 72:843–849

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Coupland SE, Foss HD, Hidayat AA, Cockerham GC, Hummel M, Stein H. “Extranodal Marginal Zone B Cell Lymphomas of the Uvea: an Analysis of 13 Cases. J Pathol 2002;197:333–340.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Coupland SE, Joussen A, Anastassiou G, Stein H. Diagnosis of a primary uveal extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma by chorioretinal biopsy: case report. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005; 243: 482–6.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Ciulla TA, Bains RA, Jakobiec FA, Topping TM, Gragoudas ES. Uveal lymphoid neoplasia: a clinical-pathologic correlation and review of the early form. Surv Ophthalmol 1997; 41: 467–76.

- ↑ Coupland, Sarah E, et al. “Primary Intraocular Lymphoma: a Review of the Clinical, Histopathological and Molecular Biological Features.” Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, vol. 242, no. 11, 2004, pp. 901–913.

- ↑ Ursea R, Heinemann MH, Silverman RH et al (1997) Ophthalmic, ultrasonographic findings in primary central nervous system lymphoma with ocular involvement. Retina 17:118–123

- ↑ Velez G, Chan CC, Csaky KG (2002) Fluorescein angiographic findings in primary intraocular lymphoma. Retina 22:37–43

- ↑ Saatci, AO, et al. “Indocyanine Green Angiographic Features of Systemic Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma and Bilateral Choroidal Involvement.” Ophthalmic Surgery and Lasers, vol. 37, no. 3, 2006, pp. 236–239.

- ↑ Shields JA, Shields C. Intraocular Tumors: Atlas and Textbook. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Wilkins and Wilkins, a Wolter Kluver business, 2008.