Unilateral Pigmentary Retinopathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease

Unilateral Pigmentary Retinopathy (UPR, sometimes also referred to as unilateral retinitis pigmentosa) refers to a rare, sporadic disorder that involves degeneration and atrophy of the retina in one eye, specifically at the level of the photoreceptors. It can mimic the appearance of Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP); however, UPR typically presents in one eye with a normal fellow eye, whereas RP presents bilaterally.[1] [2][3] [4][5] Prevalence is approximately 1 in 4000, with less than 100 cases reported in the literature.[6]

Etiology

The exact etiology of UPR is unknown. It is thought that somatic mutation during embryogenesis involves cells forming the retina and RPE (retinal pigment epithelium). Due to the mutation occurring early in embryogenesis, it has the potential to also affect germ cell lines and thus poses minimal risk to passing on the mutation to subsequent offspring.[7] [8]

UPR can be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked recessive pattern.[9] Cases have been reported with p.R677X germline mutation in the RP1 gene,[10] USH2AW4149R mutation,[7] and PDE6B mutation.[11]

Risk Factors

Genetic predisposition is a risk factor for UPR; however, there are no other known risk factors. Mutations usually involve the rhodopsin gene.

Pathophysiology

The nature of the pigmentary changes may not reliably predict the diagnosis or functional phenotype. Intraretinal pigmentary deposition, RPE depigmentation, disc pallor, and vessel attenuation can occur in UPR depending on the stage of the disease but are not pathognomonic.[12][13]

Mechanisms for the fundal appearance seen in RP of bony spicules have been studied in mouse models. [14] The pathophysiology of bone spicule formation seen in UPR occurs due to photoreceptor cell death by apoptosis. This eventually leads to the degeneration of the outer retina, causing direct contact with the inner retinal vessels and migration of the RPE cells. Extracellular matrix deposits form due to the mislocalized RPE cells that partially seal the contacting vessels.[12] [14]

Diagnosis

The criteria of Francois and Verriest for unilateral pigmentary retinopathy (i.e., idiopathic form) are the following: [15]

- functional changes and fundoscopic appearance typical for a primary pigmentary degeneration must be present in the affected eye;

- symptoms of retinal degeneration must be absent in the fellow eye with a normal ERG;

- an inflammatory, infectious, vascular cause in the affected eye must be excluded;

- the period of observation must be long enough (over 5 years) to rule out the possibility of asymmetric inherited PR (pigmentary retinopathy) .

History

In order to establish the diagnosis, it is important to get a history regarding the patient’s subjective visual perception, specifically any issues with seeing peripherally or at night. It is also important to ask about any head or eye trauma, infection, inflammation, and cancer to help rule out other retinopathies with similar fundal presentations.

Physical examination

Visual acuity: Patients present with decreased visual acuity at night (nyclopia); however, visual acuity can be variable, as cases have been reported where visual acuity has ranged from 20/15 to counting fingers.

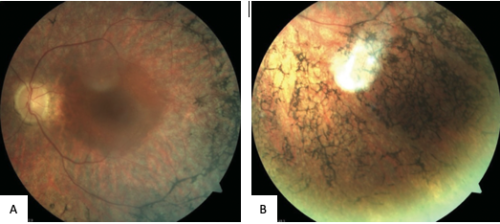

Fundus exam may reveal mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), bone-spicule formations, granular pigmentary disturbances or punched-out atrophic RPE lesions, attenuated retinal vessels, and waxy pallor of the optic disc (Figure 1).

Visual field examination: Peripheral visual field loss is common.

Symptoms

Initial symptoms of UPR include nyctalopia, peripheral visual field constriction, and occasionally loss of central visual acuity or loss of visual field.

Diagnostic Imaging

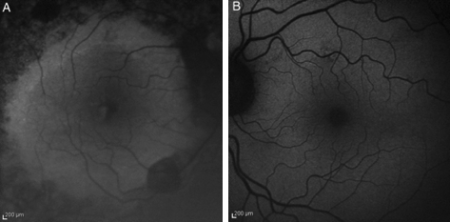

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF): Previous cases have presented with a high-density parafoveal ring of increased autofluorescence, marked loss of autofluorescence along the arcades and peripapillary area, and foci of low-density autofluorescence outside the arcades (Figure 2). Other findings have included streak-like areas of decreased autofluorescence in the macular region. [16]

Ultrasound B-scan: Some cases have been reported to show optic nerve drusen.

OCT (optical coherence tomography): OCT can show cystoid macular edema, which can present as an associated condition.

Electroretinographic (ERG): ERG can help distinguish UPR from other infectious retinopathies. ERG may show generalized retinal dysfunction in eyes with pigmentary changes. Errera et al.,[12] showed that ERG a-waves ranged from undetectable to mildly reduced in the abnormally pigmented eye with UPR. Additionally, in UPR, the b-wave latency and amplitudes are pathological, distinguishing it from syphilitic retinopathy, where only amplitudes are reduced.[16]

Laboratory test

Genetic testing and analysis can be useful to investigate the most common mutations involved in inherited retinopathies.

Differential diagnosis

There are several acquired retinal disorders with fundoscopic features that mimic RP, including those arising on a post-traumatic or postinflammatory basis. Unilateral ‘pseudo-RP’ has previously been reported in association with choroidal melanoma, [17] ocular trauma, [18] forceps related birth trauma, [19] drug toxicity (chloroquine), [20] cephaloridine, [21] oral contraceptive, [22] diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, [23] and ocular toxoplasmosis. [24]

- Trauma

o Foreign body (ie, siderosis)

o Blunt trauma (i.e., commotion retinae, retinal detachment)

- Drug toxicity

o Chloroquine

o Hydroxychloroquine

o Phenothiazine

o Thioridazine

- Post-infectious states:

o Secondary to syphilis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, Lyme disease, rubella, measles, tuberculosis

- Post-inflammatory states

o Secondary to retinal vasculitis, old posterior uveitis, diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis, acute zonal occult outer retinopathy (AZOOR)[24][25]

- Autoimmunity:

o Autoimmune Retinopathy

- Malignancy

o Carcinoma-related retinopathy (CAR)[15] [16][26]

Management

General treatment

There is no gold standard or definite treatment for patients with UPR. Supportive treatment is the standard of care. Commonly utilized treatments have included antioxidants, vitamins, and nutritional supplements but have not shown true benefit. Associated conditions, such as cystoid macular edema (CME), should be managed with appropriate medical therapy – typically, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. However, CME due to intraocular inflammation does not improve with this treatment, and it might respond to intravitreal, periocular, or oral steroids.[8] [27]

Medical follow-up

Medical follow-up should be done to monitor the progression of the disease in the affected eye as well as monitor the fellow eye to ensure the patient is not presenting with an asymmetric form of RP. Annual ocular examinations are recommended to monitor visual acuity and Goldmann visual field.

References

- ↑ 1. Weiss, J.F. and R.J. Nicholl, Nonsyphilitic unilateral retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol, 1968. 65(4): p. 573-4.

- ↑ Carr, R.E. and I.M. Siegel, Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol, 1973. 90(1): p. 21-6.

- ↑ Chen, H., et al., Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa with amblyopia in the fellow eye. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2006. 244(12): p. 1701-4.

- ↑ Grisanti, S., et al., Unilateral pigmentary degeneration of the retina associated with heterochromia iridis.Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 1998. 236(12): p. 940-4.

- ↑ Spadea, L., et al., Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa: clinical and electrophysiological report of four cases.Ophthalmologica, 1998. 212(5): p. 350-4.

- ↑ Berson, E.L., Retinitis pigmentosa. The Friedenwald Lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1993. 34(5): p. 1659-76.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Marsiglia, M., et al., Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa: a proposal of genetic pathogenic mechanisms. Eur J Ophthalmol, 2012. 22(4): p. 654-60.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Stamate, A.C., M. Burcea, and M. Zemba, Unilateral pigmentary retinopathy--a review of the literature and case presentation. Rom J Ophthalmol, 2016. 60(1): p. 47-52.

- ↑ Hartong, D.T., E.L. Berson, and T.P. Dryja, Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet, 2006. 368(9549): p. 1795-809.

- ↑ Mukhopadhyay, R., et al., Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa occurring in an individual with a germline mutation in the RP1 gene. Arch Ophthalmol, 2011. 129(7): p. 954-6.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., et al., Expanding the Clinical and Molecular Heterogeneity of Nonsyndromic Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, 2020. 22(4): p. 532-543.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Errera, M.H., et al., Unilateral pigmentary retinopathy: a retrospective case series. Acta Ophthalmol, 2019. 97(4): p. e601-e617.

- ↑ Hamel, C., Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis, 2006. 1: p. 40.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Jaissle, G.B., et al., Bone spicule pigment formation in retinitis pigmentosa: insights from a mouse model.Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2010. 248(8): p. 1063-70.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Francois, J. and G. Verriest, [Retinitis pigmentosa unilateral]. Ophthalmologica, 1952. 124(2): p. 65-88.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Weller, J.M., G. Michelson, and A.G. Juenemann, Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa: 30 years follow-up. BMJ Case Rep, 2014. 2014.

- ↑ Lommatzsch, P.K., et al., [Pseudoneuritis pigmentosa in malignant melanoma of the choroid]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1988. 193(1): p. 69-74.

- ↑ Bastek, J.V., R.Y. Foos, and J. Heckenlively, Traumatic pigmentary retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol, 1981. 92(5): p. 621-4.

- ↑ Mann I (1957): Developmental abnormalities of the eye, n.e.L.B.

- ↑ Thaler, A., P. Heilig, and J. Wiesflecker, [Unilateral pigmentary degeneration of the retina]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1980. 176(2): p. 203-6.

- ↑ Thaler, A., P. Heilig, and J. Wiesflecker, [Unilateral pigmentary degeneration of the retina]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 1980. 176(2): p. 203-6.

- ↑ Giovannini, A. and A. Consolani, Contraceptive-induced unilateral retinopathy. Ophthalmologica, 1979. 179(5): p. 302-5.

- ↑ Raymond, L.A., et al., Living retinal nematode (filarial-like) destroyed with photocoagulation. Ophthalmology, 1978. 85(9): p. 944-9.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Silveira, C., et al., Unilateral pigmentary retinopathy associated with ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol, 1989. 107(6): p. 682-4.

- ↑ Karska-Basta, I., et al., Ocular Toxoplasmosis Associated with Unilateral Pigmentary Retinopathy That May Mimic Retinitis Pigmentosa: Diagnostic Dilemmas. Medicina (Kaunas), 2021. 57(9).

- ↑ Nguyen H, S.T., Kulkarni N, Tsang S. Diagnosis and treatment of this genetic cause of photoreceptor de- generation. Retinal Physician. 2013;10:34–42.

- ↑ Strong, S., G. Liew, and M. Michaelides, Retinitis pigmentosa-associated cystoid macular edema: pathogenesis and avenues of intervention. Br J Ophthalmol, 2017. 101(1): p. 31-37.