Traumatic Optic Neuropathy

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) is a condition in which acute injury to the optic nerve from direct or indirect trauma results in vision loss. The incidence of TON has gradually increased in recent years, though this may represent better recognition. The severity of optic nerve damage in TON may range from simple contusion to complete avulsion of the optic nerve. TON is a clinical diagnosis in patients with decreased visual acuity with RAPD in the context of trauma to the globe.

Etiology

The most common cause of TON is indirect injury to the optic nerve, which is thought to be the result of transmitted shock from an orbital impact to the intracanalicular portion of optic nerve. Direct TON can result from penetrating injury or from bony fragments in the optic canal or orbit piercing the optic nerve. Orbital hemorrhage (orbital compartment syndrome) and optic nerve sheath hematoma can also cause TON by direct compression.

Risk Factors

There are no known specific risk factors for TON. However, it is important to note that TON (and trauma in general) predominantly affects younger males, with 85% of patients in the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study being male.[1] The average age of TON patients is 34 years. The most common mechanisms of injury in TON include motor vehicle accidents, bike accidents, falls, and assaults. While abusive injury is a rare cause of TON, it is an important concern in infants.

General Pathophysiology

The precise pathophysiology of indirect TON remains unclear, but it is thought to result from shearing injury in the optic nerve due to blunt head trauma, with the intracanalicular segment being identified as the most susceptible (71.4%).[2] External forces deform or fracture the narrow optic canal, subjecting the optic nerve to shear stress and vascular compromise. This shear force leads to secondary retinal ganglion cell damage. Vascular ischemia and mechanical injury cause secondary swelling. The narrow and fixed optic canal exacerbates the injury, emphasizing its significance in clinical treatment. The overall impact includes axonal damage, disrupted blood supply, optic nerve swelling, and retinal ganglion cell loss.

Direct TON occurs when foreign bodies or bony fragments impact the optic nerve directly.

TON presents a significant challenge due to the limited regenerative capacity of the ON, leading to the rapid loss of RGCs within 2 weeks through apoptosis.[3] Various physiological and biochemical factors, along with downstream signaling pathways, induce RGC apoptosis following TON. Axonal degeneration and RGC death can lead to structural and functional loss of the ON. Additionally, the immediate post-trauma phase involves the upregulation of pro-inflammatory molecules, including IL-1B and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), leading to a sterile inflammatory process. TNF is a critical regulator of immune cell function and is associated with the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative diseases. Knockout of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) has shown significant RGC protection in optic nerve injury mouse models.[4]

Axonal regeneration of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) is hindered by various molecular mechanisms, including the phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)–phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases axis, as well as the suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS3)–Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) axis. [5][6] Additionally, the Krüppel-like factor (KLF) plays a role in suppressing the axon growth capacity of RGCs and other neurons. [7] These insights pinpoint potential targets for treating traumatic optic neuropathy (TON).[8]

Primary Prevention

There is no primary prevention for TON, aside from avoidance of trauma.

Diagnosis

TON is a clinical diagnosis that can be supported by radiographic evaluation in patients with a history of craniofacial blunt injury. Like other optic neuropathies, patients with TON may have decreased visual acuity, decreased color vision, an afferent pupillary defect, and/or visual field deficits. It is important to remember that albeit rare, TON can be bilateral, so a relative afferent pupillary defect may not be seen in patients with bilateral injury and vision loss. The optic nerve head may appear normal initially, with optic atrophy becoming apparent 3-6 weeks after the initial traumatic event.

History

A history consistent with TON is vision loss immediately or shortly after blunt or penetrating head trauma. Patients may report acute unilateral decrease in vision, color vision deficits, and/or visual field deficits. The history and subjective complaints may be delayed due to the impact of and treatment for other concomitant head injuries or other systemic injuries.

Symptoms

- Vision loss

- Visual field defects

- Decreased color perception

Physical Examination

The initial external eye exam may show signs of orbital trauma or fracture (soft tissue edema, hematoma, ecchymoses, step-off on palpation of orbital rim). Decreased visual acuity and a relative afferent pupillary defect (in unilateral cases) are also seen. On fundoscopy, the initial optic nerve head assessment may be normal, but signs of optic atrophy will be seen 3-6 weeks after trauma. Clinicians should exclude a penetrating or perforating globe injury in cases of presumed TON.

Signs

- Decreased visual acuity

- Decreased color vision

- Afferent pupillary defect

- Visual field deficits

- Optic disc edema may be present, though often optic nerve appears normal initially (retrobulbar optic neuropathy) followed by optic atrophy later

Clinical Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of TON is made on the basis of a specific constellation of history and physical exam findings. Patients have a history of trauma, and complain of or are found to have significant visual loss, decreased color vision, visual field deficit, afferent pupillary defect. Dilated fundus exam is often unremarkable initially.

Diagnostic procedures

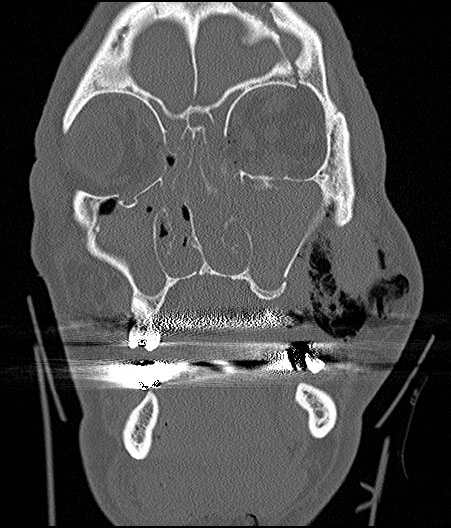

The diagnosis of TON is primarily clinical. There are some tests that can aid in the management and diagnosis of TON. It is important to obtain neuroimaging, usually a CT of the orbit with coronal and axial thin sections (1 mm) through the optic canal are crucial to visualize the optic nerve as well as the optic canal and carefully evaluate for evidence of fracture. This can help assess for compression of the optic nerve by a hematoma or bony fragments impinging on the optic nerve, which could provide an indication for urgent surgical intervention. Automated visual field testing such as a Humphrey (HVF) can be used to characterize visual field defects/scotomas in patients with TON, if acuity remains adequate for such testing. Finally, a visual evoked potential (VEP) can be used to characterize the electrical activity of the optic nerve.

Beyond optic nerve assessment, a CT can also evaluate the adjacent sphenoid-ethmoidal sinuses, while computed tomographic angiography (CTA) proves helpful in assessing the internal carotid artery (ICA). This comprehensive approach is essential for surgical planning and can aid in diagnosing concomitant craniomaxillofacial injuries. [9] [10] [11] Patients with TON can also have other traumatic complications, such as traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula (TCCF) and traumatic carotid pseudoaneurysm (TCPSA), which should be considered during the evaluation. CTA is recommended for identifying these complications. [12][13][14] This multifaceted diagnostic approach ensures a thorough evaluation and appropriate management of TON and associated injuries.[8]

Laboratory test

There are no laboratory tests to aid in the diagnosis of TON.

Differential diagnosis

- Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- Optic neuritis

- Optic nerve avulsion

- Non-organic vision loss

- Pre-/intra-/subretinal hemorrhage

- Choroidal Rupture

- Commotio retinae

Management

Aside from observation, the two treatment options that can be considered include high-dose corticosteroids or surgical decompression.[15] The management of TON is controversial, and so far, data in the literature have not shown any treatment to be superior to observation.[1][16] Spontaneous recovery has been reported in at least 15-30% of patients, and one study showed a 40% rate of spontaneous visual improvement in children with TON. [17][18]

Medical therapy

In the past, steroids were thought to have a neuroprotective effect after trauma and were used for central neurological injuries like TON. They were believed to minimize inflammation and swelling through their antioxidant properties and inhibition of free radical-induced lipid peroxidation. High-dose intravenous steroids can be considered for TON treatment, but recent studies have raised doubts about their efficacy, with no convincing evidence suggesting that steroids provide more visual benefit than observation alone. The adverse effects of steroids should also be considered. The Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head Injury (CRASH) study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of megadose steroids in patients with acute traumatic brain injury. At 6 months of follow-up, the risk of death was higher in the steroid group than in the placebo group.[19] Some animal model studies have even suggested that steroids may reduce axonal survival in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) by blocking crucial events in the endogenous neuroprotective pathway. Serious complications can occur, especially in patients with susceptibility factors such as craniofacial fractures. [20]Therefore, the use and dose of steroids in TON treatment should be considered cautiously.

Erythropoietin (EPO) has shown promise as a potential treatment for TON. EPO has demonstrated protective effects on injured RGCs by inhibiting caspase-3 activity through the PI-3-kinase/Akt pathway. Studies have reported positive neuroprotective capabilities and vision recovery in clinical TON therapy with EPO, both through intravenous and intravitreal administration. [21][22] EPO has the advantage of combining toxicological safety with RGC protection. However, more research is needed to establish its complete therapeutic effect and compare it with other treatment options.

Surgery

Surgical decompression can be considered in cases of TON with evidence of optic nerve compression, e.g., the presence of bony fragments compressing the ON or a hematoma near the ON, compressive retroorbital hemorrhage, or in blood in the optic nerve sheath. In theory, removing structures that surround the intracanalicular optic nerve decompresses the nerve, thereby alleviating ischemic changes. However, it should be noted that surgical intervention for TON was not shown to be beneficial over steroids or observation in The International Optic Nerve Trauma Study.[1]

Systematic preoperative assessments should be conducted to rule out contraindications to surgery, such as complete avulsion of the ON, traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula (TCCF) or traumatic carotid pseudoaneurysm (TCPSA). The presence of TCCF or TCPSA is an absolute contraindication to ON decompression, and immediate vascular intervention should be pursued.

Various surgical approaches have been proposed for ON decompression in TON including transcranial, external ethmoidectomy, and medial trans-orbital approaches. However, these approaches have been associated with complications such as facial bone loss, intraorbital infections, and scarring. Recently, minimally invasive approaches, such as the supraciliary keyhole approach and endoscopic transnasal/transseptal optic canal decompression (ETOCD), have been explored.[8] ETOCD, in particular, has gained attention for its effectiveness in relieving pressure on the swollen ON and improving visual outcomes. While ETOCD is less invasive, it carries certain risks and complications, including cerebrospinal fluid leakage, meningitis, monocular loss of vision, injury to the internal carotid artery (ICA), and epistaxis. [23] [24][25]

The optimal timing of intervention remains a subject of debate. Some studies suggest that intervention within 48 hours or three days of injury may yield better outcomes, while others have reported beneficial results with surgery within seven days. Timely intervention within the first two weeks of injury can be considered in TON but remains controversial. [23]

The presence of optic canal fracture (OCF) can influence the decision to pursue surgical decompression. Patients with severe OCF are associated with worse initial VA, and early surgery is recommended when a displaced bony fragment impinges on the ON. However, severe OCF with complete transection of the ON may result in irreversible damage. [26]

Complications

Serious surgical complications specific to decompression surgery for TON include infection (meningitis), CSF leaks, and exacerbation of traumatic optic neuropathy. Complications from high dose steroids include wound infection, a wide number of systemic adverse effects (i.e. GI bleed), and (for megadose) increased risk of death.

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on the extent of injury to the optic nerve. In the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study, patients with NLP vision failed to improve as often as those with better vision. This study also showed that visual acuity improvement of >3 lines on the Snellen chart was seen in 57% of the untreated group, 52% of the group that received steroids alone, and 32% of the group that underwent surgery; however, these results were not statistically different (P=0.22).[1]

Experimental Research

Experimental research is an essential area of study aimed at finding new treatments and therapies to improve the outcomes of optic nerve injuries (ONI).[8] This research focuses on various strategies, including neuroprotection, axonal regeneration, the use of neurotrophic factors [27] [28][29], stem cell transplantation [30] [31] [32] [33], RNA-based therapies, lipid metabolism [34][35][36][37], mitotherapy [38][39] [40], peripheral nerve transplantation [41] [42][43], and hypothermia [44][45][46].

Neuroprotection and Axonal Regeneration: Researchers are investigating the use of neuroprotective drugs to prevent further damage to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and promote axonal regeneration. Drugs that inhibit tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activity have shown promise in reducing RGC death and improving functional recovery in animal models of ONI. For instance, mouse models have shown promising results in reducing retinal ganglion cell loss with the use of resveratrol, an antioxidant with neuroprotective effects, after optic nerve crush injury. Other approaches, such as inhibiting nuclear factor-kappa B expression and activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3), are being explored to promote RGC survival and axonal regeneration.

Neurotrophic Factors: More than 30 neurotrophic factors have been identified that play crucial roles in the survival and regeneration of RGCs. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) have shown the potential to enhance RGC survival and axonal growth. However, the long-term effects and mechanisms of action of NFs are still under investigation.

Stem Cell Transplantation: Researchers are exploring the transplantation of various types of stem cells, including embryonic stem cells, retinal stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells, to improve RGC survival and promote regeneration. Stem cell transplantation has shown promise in improving RGC survival, reducing inflammation, and releasing neurotrophic factors that support axonal regeneration.

RNA-based Therapies: Non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs), are being investigated for their roles in nerve regeneration. MiRNAs have been found to promote axonal regeneration, while circRNAs are implicated in the early stages of disease onset.

Lipid Metabolism: The role of lipids in nerve regeneration is gaining attention. Researchers are examining changes in lipid homeostasis following neuronal injury and regeneration. Studies have shown that lipid manipulation, such as the restoration of cholesterol levels, can have a positive impact on neuroprotection and regeneration.

Hypothermia: Hypothermia, the controlled reduction of body temperature, is being explored as a protective measure for RGCs in cases of ONI. Hypothermia has shown potential in safeguarding RGCs, especially in conditions involving ischemia.

Additional Resources

- Yu Wai Man P, Griffiths PG. Surgery for traumatic optic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Oct 19;(4).

- Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG. Steroids for traumatic optic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jan 19;(1).

- http://www.trauma.org/archive/spine/steroids.html#NASCIS_1.2C_USA_1984

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Levin, L.A., et al., The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology, 1999. 106(7): p. 1268-77.

- ↑ Yu-Wai-Man P. Traumatic optic neuropathy-clinical features and management issues. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2015; 5:3–8. [DOI: 10.1016/j.tjo.2015.01.003

- ↑ Benowitz LI, Popovich PG. Inflammation and axon regeneration. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:577–583 [https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834c208d]

- ↑ Fontaine V, Mohand-Said S, Hanoteau N et al. Neurodegenerative and neuroprotective effects of tumor Necrosis factor (TNF) in retinal ischemia: opposite roles of TNF receptor 1 and TNF receptor 2. J Neurosci.2002;22:Rc216. [DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-j0001.2002]

- ↑ Duan X, Qiao M, Bei F et al. Subtype-specific regeneration of retinal ganglion cells following axotomy: effects of osteopontin and mTOR signaling. Neuron. 2015;85:1244–1256. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.017]

- ↑ Qin S, Zou Y, Zhang CL. Cross-talk between KLF4 and STAT3 regulates axon regeneration. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2633. [DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3633]

- ↑ Moore DL, Blackmore MG, Hu Y et al. KLF family members regulate intrinsic axon regeneration ability. Science. 2009;326:298–301. [DOI: 10.1126/science.1175737]

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Chen B, Zhang H, Zhai Q, Li H, Wang C, Wang Y. Traumatic optic neuropathy: a review of current studies. Neurosurg Rev. 2022;45(3):1895-1913. doi:10.1007/s10143-021-01717-9

- ↑ Morrison CS, Taylor HO, Sullivan SR. Utilization of intraoperative 3D navigation for delayed reconstruction of orbitozygomatic complex fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:e284-286. [DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31828f2a71]

- ↑ Schramm A, Suarez-Cunqueiro MM, Rücker M et al. Computer-assisted therapy in orbital and mid-facial reconstructions. Int J Med Robot. 2009;5:111–124. [DOI: 10.1002/rcs.245](https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.245)

- ↑ Udhay P, Bhattacharjee K, Ananthnarayanan P et al. Computer-assisted navigation in orbitofacial surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:995–1003. [DOI: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_807_]

- ↑ Cogbill TH, Moore EE, Meissner M et al. The spectrum of blunt injury to the carotid artery: a multicenter perspective. J Trauma. 1994;37:473–479. [https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199409000-00024]

- ↑ Ellis JA, Goldstein H, Connolly ES Jr et al. Carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;32:E9. [DOI: 10.3171/2012.2.focus1223]

- ↑ Paza AO, Farah GJ, Passeri LA. Traumatic carotid cavernous fistula associated with a mandibular fracture. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:86–89. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.06.015]

- ↑ He Z, Li Q, Yuan J, et al. Evaluation of transcranial surgical decompression of the optic canal as a treatment option for traumatic optic neuropathy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. Jul 2015;134:130-5. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.04.023

- ↑ Wladis EJ, Aakalu VK, Sobel RK, McCulley TJ, Foster JA, Tao JP, Freitag SK, Yen MT. Interventions for Indirect Traumatic Optic Neuropathy: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020 Nov 6:S0161-6420(20)31041-1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.10.038. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33161071.

- ↑ Wolin MJ, Lavin PJ. Spontaneous visual recovery from traumatic optic neuropathy after blunt head injury. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:430–435. [DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74609-4]

- ↑ Mahapatra AK, Tandon DA.Traumatic optic neuropathy in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Neurosurg 1993.19:34–39.https://doi.org/10.1159/000120698

- ↑ Edwards, P., et al., Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury-outcomes at 6 months. Lancet, 2005. 365(9475): p. 1957-9.

- ↑ Li H, Zhou B, Shi J et al. Treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: our experience of endoscopic optic nerve decompression. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1325–1329. [DOI: 10.1017/s0022215108002296]

- ↑ Entezari M, Esmaeili M, Yaseri M. A pilot study of the effect of intravenous erythropoetin on improvement of visual function in patients with recent indirect traumatic optic neuropathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. Aug 2014;252(8):1309-13. doi:10.1007/s00417-014-2691-6

- ↑ Kashkouli MB, Pakdel F, Sanjari MS, et al. Erythropoietin: a novel treatment for traumatic optic neuropathy-a pilot study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. May 2011;249(5):731-6. doi:10.1007/s00417-010-1534-3

- ↑ Jump up to: 23.0 23.1 Dhaliwal SS, Sowerby LJ, Rotenberg BW. Timing of endoscopic surgical decompression in traumatic optic neuropathy: a systematic review of the literature. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:661–667. [DOI: 10.1002/alr.21706](https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.21706)

- ↑ Ma YJ, Yu B, Tu YH et al. Prognostic factors of trans-ethmosphenoid optic canal decompression for indirect traumatic optic neuropathy. Int J Ophthalmol. 2018;11:1222–1226. [DOI: 10.18240/ijo.2018.07.24]

- ↑ Yu B, Chen Y, Ma Y et al. Outcome of endoscopic trans-ethmosphenoid optic canal decompression for indirect traumatic optic neuropathy in children. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:152. [DOI: 10.1186/s12886-018-0792-4]

- ↑ Yan W, Chen Y, Qian Z et al (2017) Incidence of optic canal fracture in the traumatic optic neuropathy and its effect on the visual outcome. Br J Ophthalmol 101:261–267. (https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308043)

- ↑ Bhattacharyya A, Watson FL, Bradlee TA et al. Trk receptors function as rapid retrograde signal carriers in the adult nervous system. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7007–7016. [https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.17-18-07007.1997](https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.17-18-07007.1997)

- ↑ Chen H, Weber AJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces TrkB protein and mRNA in the normal retina and following optic nerve crush in adult rats. Brain Res. 2004;1011:99–106. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.024]

- ↑ Zuo, et al. SIRT1 promotes RGC survival and delays loss of function following optic nerve crush. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 26;54(7):5097-102

- ↑ Feng X, Chen P, Zhao X et al. Transplanted embryonic retinal stem cells have the potential to repair the injured retina in mice. BMC Ophthalmol. 2021;21:26. [DOI: 10.1186/s12886-020-01795-1]

- ↑ Haddad-Mashadrizeh A, Bahrami AR, Matin MM et al. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells can survive and integrate into the adult rat eye following xenotransplantation.

- ↑ Hambright D, Park KY, Brooks M, McKay R, Swaroop A, Nasonkin IO. Long-term survival and differentiation of retinal neurons derived from human embryonic stem cell lines in un-immunosuppressed mouse retina. Mol Vis. 2012;18:920-936.

- ↑ Lin TC, Hsu CC, Chien KH et al. Retinal stem cells and potential cell transplantation treatments. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77:556–561. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.08.001]

- ↑ Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME. Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: the precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:183–193. [https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3176]

- ↑ Goldberg JL. How does an axon grow? Genes Dev. 2003;17:941–958. [DOI: 10.1101/gad.1062303]

- ↑ Pfenninger KH. Plasma membrane expansion: a neuronʼs Herculean task. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:251–261. [DOI: 10.1038/nrn2593]

- ↑ Vance JE, Campenot RB, Vance DE. The synthesis and transport of lipids for axonal growth and nerve regeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1486:84–96. [DOI: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00050-0](https://doi.org/10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00050-0)

- ↑ Fu A, Shi X, Zhang H et al. Mitotherapy for fatty liver by intravenous administration of exogenous mitochondria in male mice. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:241. [DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00241]

- ↑ Robicsek O, Ene HM, Karry R et al. Isolated mitochondria transfer improves neuronal differentiation of schizophrenia-derived induced pluripotent stem cells and rescues deficits in a rat model of the disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:432–442. [DOI: 10.1093/schbul/sbx077]

- ↑ Wang R, Sun Q, Xia F et al. Methane rescues retinal ganglion cells and limits retinal mitochondrial dysfunction following optic nerve crush. Exp Eye Res. 2017;159:49–57. [DOI: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.03.008]

- ↑ Aguayo AJ, Rasminsky M, Bray GM et al. Degenerative and regenerative responses of injured neurons in the central nervous system of adult mammals. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;331:337–343. [https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1991.0025]

- ↑ Cen LP, Luo JM, Geng Y et al. Long-term survival and axonal regeneration of retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve transection and a peripheral nerve graft. NeuroReport. 2012;23:692–697. [https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0b013e328355f1d6](

- ↑ Zuo KJ, Shafa G, Antonyshyn K et al. A single session of brief electrical stimulation enhances axon regeneration through nerve autografts. Exp Neurol. 2020;323:113074. [DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113074]

- ↑ Faberowski N, Stefansson E, Davidson RC. Local hypothermia protects the retina from ischemia. A quantitative study in the rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30:2309–2313.

- ↑ Rey-Funes M, Larrayoz IM, Contartese DS et al. Hypothermia prevents retinal damage generated by optic nerve trauma in the rat. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6966. [DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-07294-6]

- ↑ Salido EM, Dorfman D, Bordone M et al. Global and ocular hypothermic preconditioning protect the rat retina from ischemic damage. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61656. [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061656]