Traumatic Horner Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Background

Horner syndrome, known classically by its presenting triad of miosis (pupillary constriction), eyelid ptosis (drooping), and facial anhidrosis (decreased sweating), results from damage to the sympathetic pathways between the hypothalamus and ocular adnexa. [1][2] In clinical practice, however, definitive diagnosis can be challenging as patients rarely present with the complete triad of signs and symptoms.[3] Figure 1 demonstrates the classic appearance of a left-sided Horner syndrome with apparent pupillary miosis and ipsilateral eyelid ptosis.

Although Horner syndrome can result from a variety of mechanisms (Table 1), the most common etiologies are neoplastic (35-60% of all cases). Other less common causes include iatrogenic injury (10-18.5%) and trauma (4-13% inclusive of birth-related injuries).[4] This article specifically focuses on the diagnosis and management of traumatic Horner syndrome.

Table 1. Etiologies of Horner Syndrome[4][5]

| Malignant Tumors |

|

| Benign Tumors |

|

| Neural |

|

| Vascular |

|

| Infectious |

|

| Iatrogenic |

|

| Traumatic |

|

| Other |

|

Anatomy

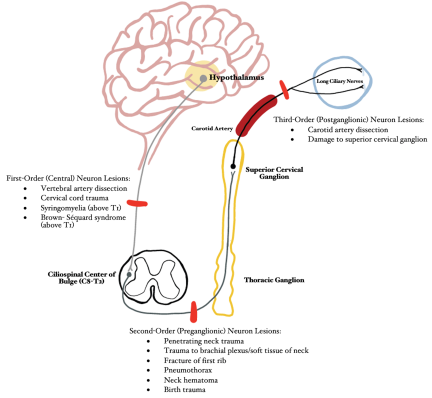

Horner syndrome is caused by a lesion to the first, second, and/or third order neurons that comprise the sympathetic pathways that innervate the head and neck. The long anatomical pathway of the oculosympathetic chain makes it particularly vulnerable to many pathological processes and injuries.[6] Pupil size is mediated by autonomic control of iris constriction and dilation and is based upon both endogenous and exogenous mediators along with physiological stimuli. Pupillary constriction is controlled by parasympathetic fibers, originating in the ciliary ganglia, that innervate the pupillary constrictor muscle. In contrast, pupillary dilation is mediated by sympathetic fibers, originating from the superior cervical ganglion, that innervate the pupillary dilator muscle.[7] Damage to the sympathetic pathway thereby limits the ability for the pupil to dilate, resulting in ipsilateral miosis secondary to unopposed pupillary constriction by the intact parasympathetic system. The following section summarizes the impact of common mechanisms of trauma at various anatomic locations along the oculosympathetic chain (Figure 2):

First-Order (Central) Neuron: Hypothalamus → Ciliospinal Center of Budge (C8-T2)

- Vertebral artery dissection: Motor vehicle accident (MVA), blunt neck trauma, strangulation, chiropractic manipulation, sudden neck movements, severe coughing[8]

- Cervical cord trauma (MVA, falls, penetrating or blunt trauma, sport-related or diving injuries)[9]

- Post-traumatic late-stage syringomyelia (if above T1)[10]

- Brown-Séquard syndrome (if above T1)

Second-Order (Preganglionic) Neuron: Ciliospinal Center of Budge (C8-T2) → Superior Cervical Ganglion

- Penetrating neck trauma (stab wounds, gunshot wounds)[11][12]

- Trauma to brachial plexus/soft tissue of neck[12]

- Fracture of the first rib [1]

- Pneumothorax [1]

- Neck Hematoma [1]

- Birth trauma [13]

Third-Order (Postganglionic) Neuron: Superior Cervical Ganglion → Pupillary Dilator Muscles of Iris and Smooth Muscle of Upper and Lower Eyelid (Muller muscle)

- Carotid Artery Dissection[14]

- Damage to superior cervical ganglion (due to penetrating intraoral injury)[15]

Birth trauma (complex vaginal delivery, forceps, etc.)[16] may result in Horner syndrome, most commonly at the level of the second-order neuron,[13] and can be associated with concomitant brachial plexus injury.[17]

Pupil examination: Anisocoria

Given the broad differential diagnosis associated with head and neck trauma, it is critical to rule out potentially life-threatening diagnoses that can be associated with pupil asymmetry (anisocoria) and ptosis. A prompt and comprehensive neuro-ophthalmic examination is critical to differentiate if the larger pupil is too dilated (mydriatic), or if the smaller pupil is too constricted (miotic). Optimizing ambient lighting conditions and using a bright light source in both dim and illuminated settings will help make this critical differentiation.

If the anisocoria is greater in bright illumination, then the eye with the larger pupil is the affected eye. In this case, a contralateral Horner Syndrome can be ruled out, and attention can be directed to disorders of the parasympathetic system (Adie tonic pupil, postsurgical mydriasis, secondary glaucoma, pupillary synechiae, oculomotor nerve palsy, pharmacological/narcotic contaminants, etc.) (Table 2) in the mydriatic eye.

If the anisocoria is greater in dim illumination, then the eye with the miotic pupil is likely abnormal, and an ipsilateral Horner syndrome remains a possibility.[12] Additionally, in the setting of Horner syndrome, as opposed to many causes of abnormal large pupil, both pupils will remain briskly reactive to light. It is important to note that mild (up to 1mm) physiological anisocoria is present in up to 15-30% of the normal population[18] and is not associated with central nervous system pathology. This physiological type of anisocoria is characterized by a stable difference in size in both bright and dim ambient lighting.

Pharmacologic testing with topical cocaine, apraclonidine, hydroxyamphetamine, or phenylephrine may be helpful in confirming the presence of Horner syndrome or locating which order nerve is involved.[19] More information about these tests can be found at https://eyewiki.org/Horner_Syndrome#Examination.

Small pupils in settings of anisocoria may also be secondary to uveitis, eye trauma, diabetic eye disease, topical eye drops or ocular surface contaminants (pilocarpine, narcotics, parasympathomimetics), postoperative changes, etc.

Eyelid Evaluation: Ptosis

The presence of concomitant ptosis with pupillary miosis should place Horner syndrome high on the differential, particularly if accompanied by anhidrosis. Ptosis, however, can occur for a variety of reasons. The clinician may consider whether the asymmetry in lid position is due to ipsilateral ptosis, versus contralateral eyelid retraction. For example, if manual elevation of the ptotic lid results in lowering of the contralateral eyelid (positive Hering’s Test), this is indicative of ipsilateral ptosis with compensatory lifting. Hertel exophthalmometry should also be performed to rule out lid changes secondary to proptosis of the contralateral eye.[20]

Table 2. Differential Diagnosis for Anisocoria/Ptosis[12][21][22][23]

| Anisocoria |

|

| Ptosis |

|

Clinical Evaluation

In the setting of trauma, a thorough history obtained from all available sources (patient, family, witnesses, first responders, etc.) focused on the mechanism of action, along with any relevant neurological and ophthalmic history, may help to guide further workup, radiological studies, and consultation. Of note, close coordination with the emergency department, nursing, and any consulting doctors (neurology, neurosurgery, etc.), particularly before performing pharmacological testing, is essential to avoid medical errors. For more detailed information on clinical examination and pharmacological tests, visit: https://eyewiki.org/Horner_Syndrome#Examination.

While some trauma may be obvious, dissections of the internal carotid artery and resultant Horner syndrome may occur with seemingly minor trauma (eg, chiropractic manipulation, roller coaster riding, etc).[24][25] An acute painful Horner syndrome should be considered a dissection of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery until proven otherwise. These patients are at high risk for cerebral infarction, and this is an emergency. Of note, a study of 146 patients with cervical internal carotid artery dissection, Horner syndrome was the initial and sole manifestation in half of these cases.[14]

Traumatic Horner syndrome in the pediatric patient may occur due to birth trauma or complicated deliveries. However, when faced with a child with Horner syndrome, the primary focus should be ruling out thoracic and cervical neuroblastoma.

Management/Treatment

Acute onset of Horner syndrome should be evaluated immediately to further prevent trauma-associated injury and, specifically, to prevent stroke secondary to an internal carotid artery dissection. Importantly, Horner syndrome itself does not generally result in major functional deficits, and concerns are generally cosmetic. The focus of the physician should be to expeditiously evaluate for dangerous or life-threatening underlying causes.

Imaging techniques for identifying a carotid dissection include CT angiography, MRI and MRA, carotid duplex imaging, and digital subtraction angiography. Given the advantages and disadvantages of each of these modalities, appropriate imaging can be tailored to the clinical scenario.[26] Identification of a carotid dissection requires emergent management in cooperation with vascular neurology, including antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy.[27]

Temporary correction of the eyelid position can be achieved with the use of topical medications or hyaluronic acid gel injections.[28][29][30] Surgical ptosis repair can provide a more permanent restoration of facial and eyelid symmetry.[31][12][32]

Summary

Horner syndrome results from disruption of the oculosympathetic pathways, and is associated with ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis, although patients may not present with this complete triad. Although there are many causes of Horner syndrome, head, neck, and chest trauma can precipitate the syndrome. Of note, carotid artery dissection, particularly in the setting of trauma, should be considered an emergency. Careful neuro-ophthalmic evaluation can help differentiate Horner syndrome from other disease entities that impact pupil and eyelid anatomy and physiology. Once a diagnosis has been made, treatment is targeted to the underlying condition, and may include cosmetic treatments to improve lid and facial asymmetry.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kanagalingam, S., & Miller, N. R. (2015). Horner syndrome: clinical perspectives. Eye and Brain, 7, 35–46. https://doi.org/10.2147/EB.S63633

- ↑ Paiva, W. S., De Amorim, R. L. O., Tavares, W. M., Alho, E. J. L., Jeng, B. P., & Figueiredo, E. G. (2007). Horner’s syndrome after blunt cervical and chest trauma: case report. Arquivos De Neuro-Psiquiatria, 65(4A), 1037–1039. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282x2007000600026

- ↑ Eggenberger, E. R., & Pula, J. H. (2014). Chapter 24 - Neuro-ophthalmology in Medicine. In M. J. Aminoff & S. A. Josephson (Eds.), Aminoff’s Neurology and General Medicine (Fifth Edition) (pp. 479–502). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407710-2.00024-2

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Bell, R. L., Atweh, N., Ivy, M. E., & Possenti, P. (2001). Traumatic and iatrogenic Horner syndrome: case reports and review of the literature. The Journal of Trauma, 51(2), 400–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200108000-00034

- ↑ Horner Syndrome - American Academy of Ophthalmology. (n.d.). Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.aao.org/oculoplastics-center/horner-syndrome-8

- ↑ Davagnanam, I., Fraser, C. L., Miszkiel, K., Daniel, C. S., & Plant, G. T. (2013). Adult Horner’s syndrome: a combined clinical, pharmacological, and imaging algorithm. Eye, 27(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.281

- ↑ McDougal, D. H., & Gamlin, P. D. (2014). Autonomic Control of the Eye. In R. Terjung (Ed.), Comprehensive Physiology (1st ed., pp. 439–473). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c140014

- ↑ Britt, T. B., & Agarwal, S. (2022). Vertebral Artery Dissection. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441827/

- ↑ Torlincasi, A. M., & Waseem, M. (2022). Cervical Injury. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448146/

- ↑ Kerrison, J. B., Biousse, V., & Newman, N. J. (2000). Isolated Horner’s syndrome and syringomyelia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 69(1), 131–132. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.69.1.131

- ↑ Sayan, M., & Çelik, A. (2014). The Development of Horner Syndrome following a Stabbing. Case Reports in Medicine, 2014, e461787. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/461787

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Martin, T. J. (2018). Horner Syndrome: A Clinical Review. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 9(2), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00405

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Pollard, Z. F. (2010). Atypical Acquired Pediatric Horner Syndrome. Archives of Ophthalmology, 128(7), 937. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.119

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Biousse, V., Touboul, P. J., D’Anglejan-Chatillon, J., Lévy, C., Schaison, M., & Bousser, M. G. (1998). Ophthalmologic manifestations of internal carotid artery dissection. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 126(4), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00136-6

- ↑ Liu, G. T., Deskin, R. W., & Bienfang, D. C. (1992). Horner’s syndrome caused by intra-oral trauma. Journal of Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology, 12(2), 110–115.

- ↑ George, N. D. L., Gonzalez, G., & Hoyt, C. S. (1998). Does Horner’s syndrome in infancy require investigation? British Journal of Ophthalmology, 82(1), 51–54. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.82.1.51

- ↑ Jeffery, A. R., Ellis, F. J., Repka, M. X., & Buncic, J. R. (1998). Pediatric Horner syndrome. Journal of AAPOS: The Official Publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, 2(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90008-8

- ↑ Lam, B. L., Thompson, H. S., & Corbett, J. J. (1987). The Prevalence of Simple Anisocoria. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 104(1), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9394(87)90296-0

- ↑ Smit DP. Pharmacologic testing in Horner's syndrome - a new paradigm. S Afr Med J. Nov 09 2010;100(11):738-40. doi:10.7196/samj.3773

- ↑ Koka, K., & Patel, B. C. (2022). Ptosis Correction. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539828/

- ↑ Shahzad, B., & Siccardi, M. A. (2022). Ptosis. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546705/

- ↑ Payne, W. N., Blair, K., & Barrett, M. J. (2022). Anisocoria. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470384/

- ↑ Horner Syndrome - EyeWiki. (n.d.). Retrieved April 17, 2022, from https://eyewiki.org/Horner_Syndrome

- ↑ Badve MS, Bhuta S. Roller coasters and cervical artery dissection. Med J Aust. 2015 Oct 19;203(8):339. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00715.

- ↑ Ernst E. Ophthalmological adverse effects of (chiropractic) upper spinal manipulation: evidence from recent case reports. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005 Oct;83(5):581-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00488.x.

- ↑ Hakimi R, Sivakumar S. Imaging of Carotid Dissection. Curr Pain Headache Rep. Jan 19 2019;23(1):2. doi:10.1007/s11916-019-0741-9

- ↑ Markus HS, Levi C, King A, Madigan J, Norris J, for the Cervical Artery Dissection in Stroke Study (CADISS) Investigators. Antiplatelet Therapy vs Anticoagulation Therapy in Cervical Artery Dissection: The Cervical Artery Dissection in Stroke Study (CADISS) Randomized Clinical Trial Final Results. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(6):657–664. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0072

- ↑ Wirta DL, Korenfeld MS, Foster S, Smyth-Medina R, Bacharach J, Kannarr SR, Jaros MJ, Slonim CB. Safety of Once-Daily Oxymetazoline HCl Ophthalmic Solution, 0.1% in Patients with Acquired Blepharoptosis: Results from Four Randomized, Double-Masked Clinical Trials. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021 Oct 8;15:4035-4048. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S322326. PMID: 34675472; PMCID: PMC8517985.

- ↑ Mancini R, Khadavi NM, Goldberg RA. Nonsurgical management of upper eyelid margin asymmetry using hyaluronic acid gel filler. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jan-Feb;27(1):1-3. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181c2a16d. PMID: 20551854.

- ↑ Garibaldi DC, Hindman HB, Grant MP, Iliff NT, Merbs SL. Effect of 0.5% apraclonidine on ptosis in Horner syndrome. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jan-Feb;22(1):53-5. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000196322.05586.6a. PMID: 16418668.

- ↑ Glatt HJ, Putterman AM, Fett DR. Muller's muscle-conjunctival resection procedure in the treatment of ptosis in Horner's syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990 Feb;21(2):93-6. PMID: 2330204.

- ↑ Pang NK, Newsom RW, Oestreicher JH, Chung HT, Harvey JT. Fasanella-Servat procedure: indications, efficacy, and complications. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008 Feb;43(1):84-8. doi: 10.3129/i07-181. PMID: 18219349.