All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease entity

- ICD-10: E05.00

Disease

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is an autoimmune disease caused by the activation of orbital fibroblasts by autoantibodies directed against thyroid receptors. TED is a rare disease that had an incidence rate of approximately 19 in 100,000 people per year in 1 study.[1] The disorder is characterized by inflammation and swelling of the extraocular muscles, fatty tissue, and connective tissue within the orbit. Graves disease (GD) is an autoimmune disorder involving the thyroid gland. It is typically characterized by the presence of circulating autoantibodies that bind to and stimulate the thyroid hormone receptor (TSHR), resulting in hyperthyroidism and goiter. Organs other than the thyroid can also be affected, leading to the extrathyroidal (outside the thyroid gland itself) manifestations of GD. TED is observed in ~ 50% of patients, whereas Graves dermopathy and acropachy are quite rare.[2] TED was previously known as thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO), Graves orbitopathy (GO), and other variations.

Etiology

TED is most frequently associated with hyperthyroidism, constituting of approximately 90% of the cases. However, about 10% of patients with TED have either a normal-functioning (euthyroid) or under-functioning thyroid (hypothyroidism, eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis). Although strict control of thyroid function is crucial in patients with TED, the course and severity of ocular manifestation does not always correlate with thyroid hormone levels. Thus, treatment of thyroid dysfunction does not necessarily affect the course of Graves ophthalmopathy.

Risk factors

TED includes genetic, environmental, and immune risk factors. Among the environmental factors, smoking is the most consistently linked risk factor to the development or worsening of the disease.[3] The risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day, and giving up smoking has been linked with reduced risk. Stress is another environmental factor that may contribute to the worsening of TED.[4] Patients treated with radioactive iodine may experience worsening of TED, especially if they are smokers.[2]

Epidemiology

TED has a higher prevalence in women than in men. Both men and women demonstrate a bimodal pattern of the age of diagnosis. The median age is 43 years for all patients, with a range from 8 to 88 years old. Women are affected 5 times more than men, and this has been linked to a higher incidence of Graves disease in women. Patients diagnosed after age 50 years have a worse prognosis overall.[1]

Pathophysiology

Although the underlying mechanisms of action of these processes are not completely understood, the presumed mechanism is activation of orbital fibroblasts by Graves disease-related autoantibodies, which lead to the release of T-cell chemoattractants, initiating an interaction that ultimately results in fibroblasts expressing extracellular matrix molecules, biologic materials proliferating and differentiating into myofibroblasts or lipofibroblasts, and deposition of glycosaminoglycans, which bind water that leads to swelling and congestion in addition to connective tissue remodeling. This results in extraocular muscle enlargement and orbital fat expansion.

Diagnosis

History/Symptoms

The patient complains of gritty sensations, photophobia, lacrimation, dry eye, discomfort, and forward protrusion of the eye. In more advanced cases, patients may have eye socket (orbital) pain, double vision, or blurred vision.

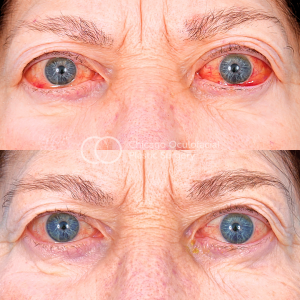

Signs

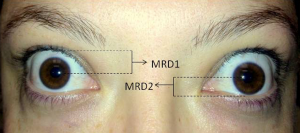

- Eyelid retraction (Dalrymple sign) is the most common presenting sign of TED, found in up to 90% of patients.[5]

- Lid lag of the upper eyelid on downward gaze (Von Graefe sign) and lid edema.[6]

- TED is the most common cause for both unilateral and bilateral axial proptosis (exophthalmos). There is increased resistance to retropulsion. The Hertel exophthalmometer is used for the measurement of proptosis.

- Bulbar conjunctiva may be injected (Goldzeiher sign). Exposure keratopathy ocular emergency can occur further due to lagophthalmos, which is a major cause for decrease in visual acuity and in blurred vision in TAO, apart from compressive optic neuropathy.

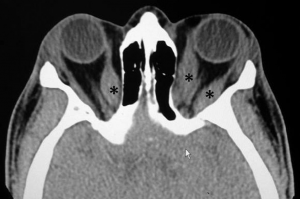

- Extraocular muscles are frequently involved in TAO. The most commonly affected muscle is the inferior rectus, followed by the medial, superior, levator, lateral rectus, and oblique (mnemonic: “I'M SLOw”). Extraocular muscles can affect results in ocular misalignment and diplopia. There can also be an inability to look up when the eye is adducted, which is termed double elevator palsy.

- Compressive optic neuropathy is an ocular emergency. It occurs in <5% of patients with typical TED and results in slowly progressive fulminant visual loss. It occurs due to compression from the oversized recti and orbital fat, causing compartment syndrome at the apex of orbit. It is characterized by decrease in vision, color vision, and contrast sensitivity, and development of relative afferent papillary defect. The characteristic visual fields commonly show central, cecocentral, paracentral, and nerve fiber layer bundle defects. Optic nerve head examination can be normal or show optic disc edema or pallor.

- Clinical course: TED typically has a progressive inflammatory phase, followed by a stable postinflammatory phase.

- The pattern of the disease follows the Rundle curve, which describes the plot of orbital disease severity against time.

- Initial phase: inflammatory phase duration may last from 6 to 18 months, with orbital and periorbital signs including proptosis and retraction

- Static phase: decrease in the inflammatory phase and minimal improvement

- Quiescent phase: gradual improvement with improved motility and retraction of the muscles

- The upper lid signs in TED include:

- Stellwag sign: incomplete and frequent blinking

- Grove sign: resistance in pulling the retracted upper eyelid

- Boston sign: jerky movements of eyelids in downgaze

- Gifford sign: difficulty while everting the upper eyelid

- Gellineck sign: abnormal pigmentation of the upper eyelid

- The lower lid signs in TED include:

- Enroth sign: lower eyelid edema

- Griffith sign: lid lag on upgaze

- The conjunctival signs include:

- Goldzeiher sign: conjunctival injection

- The extraocular movements signs include:

- Mobius sign: not able to converge eyes

- Ballet sign: one or more extraocular muscle restriction

- Suker sign: poor fixation in abduction

- Jendrassik sign: paralysis of all EOM

- The pupillary signs-

- Knies sign: uneven pupillary dilatation in dim light

- Cowen sign: jerky contraction of the pupil to light

- Generalized signs

- Vigouroux sign: eyelid fullness

- Von Graefe sign: retarded descent of upper lid in downgaze

- Jofforoy sign: absent crease of the forehead in superior gaze

- Kocher sign: staring and frightened appearance of eyes

Diagnostic procedures

Laboratory test

The diagnosis can be done clinically with the characteristic clinical picture, restrictive nature of the disease, and associated systemic thyroid disease. Although not diagnostic, thyroid hormone levels, thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI), and anti thyroid antibodies can be suggestive of diagnosis.

Ultrasonography: Both A-scan and B-scan transocular echograms can be used to visualize the orbital structures and to determine recti muscle enlargement. Advantage is its low cost, lack of ionizing radiation, and relatively short examination time.

Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scan: This type of imaging without contrast may distinguish normal structures from abnormal structures of different tissue density. It demonstrates enlargement of the bellies and sparing of the tendons. It helps in assessing the relationship between the optic nerve and muscles at the apex, which helps in planning for the surgical intervention, if needed.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Fusiform rectus enlargement and orbital fat expansion may be identified. MRI may also aide in assessing water content in the muscles and other soft tissues. This may correlate with active inflammation.

Differential diagnosis

- Orbital pseudotumor

- Caroticocavernous fistula

- Inflammatory orbitopathy, eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Orbital myositis (OM)

- Orbital tumors

- IgG4 disease

Grading

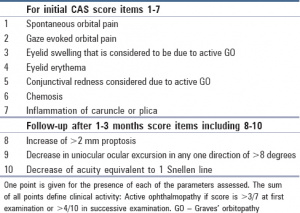

Werner reported the NO SPECS (Nophysical signs or symptoms, Only signs, Soft tissue involvement, Proptosis, Extraocular muscle signs, Corneal involvement, and Sight loss) Classification system in 1969 and a modified version was published in 1977. What is worth noting is that this system grades on disease severity and not the activity of the disease.

A shift in treatment began in 1989 when the clinical activity score (CAS) was created to help distinguish the active and stable phases of the disease. Its distinguishing feature is grading classic signs of acute inflammation. A CAS ≥3/7 is indicative of active disease. [7]

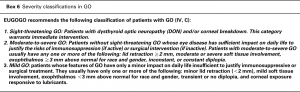

The most current grading systems of TED are the VISA (vision, inflammation, strabismus, and appearance) classification and the European Group of Graves Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) classification. [8] The utility of these grading systems is that both assess severity and activity.

In the VISA classification, the 4 severity parameters can be found in the name, and a maximum score of 20 is used to grade the severity of disease. Each of the 4 parameters has further divisions in order to better assess the activity of the disease; the form can be found at (http://www.thyroideyedisease.org).[9]

EUGOGO classification attempts to assess both disease activity and disease severity. Activity is based on 4 measures of inflammation, pain, redness, swelling, and impaired function, and function is graded with decreasing monocular motion and diminishing visual acuity. The classification system also has developed an image atlas that can be used to accurately grade the patient who is being examined. Additionally, the EUGOGO grading system does well in differentiating management categories.[10]

Management

Conservative: Both smoking cessation and euthyroid status help prevent further exacerbation and decrease the duration of active disease.[11] For corneal exposure, lubricants, taping, and protective shields can be tried, and if necessary, tarsorrhaphy can be done. For diplopia, Fresnel prisms or occlusion therapy may be considered. Others are lifestyle modifications, including sodium restriction to reduce water retention and tissue edema. Sleeping with the head of the bed elevated to decrease orbital edema is also useful. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be used for periocular pain. Selenium has shown significant benefit in patients with mild, noninflammatory orbitopathy.[12]

Teprotumumab:  This biologic infusion therapy has been shown in clinical studies to reduce signs and symptoms of TED.[13][14] Teprotumumab binds to IGF-1R and blocks its activation and signaling. Tepezza (Teprotumumab-trbw) is the first and only FDA-approved prescription treatment for TED.

Systemic steroids: To decrease orbital inflammation oral, prednisone in a dose of 1- 1.5-mg/ kg can be given for a suggested maximum period of 2 months. Pulse-dosed IV dexamethasone followed by oral prednisone can be considered as an alternative when oral prednisone alone fails to control the inflammation.

Orbital Radiation: This method can be used alone or in conjunction with corticosteroids The radiation therapy works on the similar mechanism of decreasing inflammation. A typical dose of 2000 cGy for each orbit 200 cGy / day is given over a period 10 days. It generally improves vertical motility. Radiation retinopathy may occur as a side effect.

Orbital Decompression: This surgical procedure enlarges the existing space of the orbit by partial removal of bony walls. Orbital decompression commonly involves the orbital floor, medial wall, and lateral wall. In rare cases, the roof of the orbit may also be decompressed surgically.

Strabismus surgery: In cases of significant strabismus, strabismus surgery may be required and should be done with adjustable sutures, since the muscles typically do not respond as normal muscles would to strabismus surgery. Strabismus surgery should be considered only after orbital decompression is complete and muscle alignment has stabilized.

Eyelid Retraction Repair and Tarsorrhaphy : These reconstructive surgical procedures may be preformed to address eyelid retraction or exposure keratitis.

Alternative Treatments: Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that targets CD‐20 on B‐cells.[15][16]

Additional Resources

- What Is Graves’ Disease? American Academy of Ophthalmology. EyeSmart/Eye health. https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-graves-disease. Accessed April 3, 2023.

- Patient Information Brochure. North American Neuro Ophthalmology Society (NANOS). https://www.nanosweb.org/i4a/pages/TED_information_brochure. Accessed March 3, 2025

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Bartley, G. B. (1994). The epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of ophthalmopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society, 92, 477.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Menconi, F., Marcocci, C., & Marinò, M. (2014). Diagnosis and classification of Graves' disease. Autoimmunity reviews, 13(4-5), 398-402.

- ↑ Thornton, J., Kelly, S. P., Harrison, R. A., & Edwards, R. (2007). Cigarette smoking and thyroid eye disease: a systematic review. Eye, 21(9), 1135-1145.

- ↑ Mizokami, T., Wu Li, A., El-Kaissi, S., & Wall, J. R. (2004). Stress and thyroid autoimmunity. Thyroid, 14(12), 1047-1055.

- ↑ Phelps PO, Williams K. Thyroid Eye Disease for the Primary Care Practitioner. Dis.Mon 60(2014)292–298. [PMID 24906675]

- ↑ Albert and Jakobiec's Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology; Albert D M, Miller J W; 3rd edition- chapter 229- 230: page 2913-37.

- ↑ Bartalena L, Kahaly GJ, Baldeschi L, Dayan CM, Eckstein A, Marcocci C, et al. The 2021 European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021; 185: G43–67.

- ↑

Barrio-Barrio J, Sabater AL, Bonet-Farriol E, Velázquez-Villoria Á, Galofré JC. Graves' Ophthalmopathy: VISA versus EUGOGO Classification, Assessment, and Management. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:249125. doi: 10.1155/2015/249125. Epub 2015 Aug 17. PMID: 26351570; PMCID: PMC4553342. - ↑ http://www.thyroideyedisease.org

- ↑ Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Dickinson A, Eckstein A, Kendall-Taylor P, Marcocci C, Mourits M, Perros P, Boboridis K, Boschi A, Currò N, Daumerie C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Lane CM, Lazarus JH, Marinò M, Nardi M, Neoh C, Orgiazzi J, Pearce S, Pinchera A, Pitz S, Salvi M, Sivelli P, Stahl M, von Arx G, Wiersinga WM; European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy (EUGOGO). Consensus statement of the European Group on Graves' orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of GO. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008 Mar;158(3):273-85. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0666. PMID: 18299459.

- ↑ Bartalena L, Pinchera A, Marcocci C. Management of Graves' ophthalmopathy: reality andperspectives. Endocr Rev 2000;21(2):168‐199. [PMID 10782363]

- ↑ Drutel, A., Archambeaud, F., & Caron, P. (2013). Selenium and the thyroid gland: more good news for clinicians. Clinical endocrinology, 78(2), 155-164.

- ↑ Douglas, R. S., Kahaly, G. J., Patel, A., Sile, S., Thompson, E. H., Perdok, R., ... & Antonelli, A. (2020). Teprotumumab for the treatment of active thyroid eye disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(4), 341-352.

- ↑ Smith, T. J., Kahaly, G. J., Ezra, D. G., Fleming, J. C., Dailey, R. A., Tang, R. A., ... & Gigantelli, J. W. (2017). Teprotumumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(18), 1748-1761.

- ↑ Stan MN, Garrity JA, Carranza Leon BG, Prabin T, Bradley EA, Bahn RS. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab in patients with Graves' orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100(2):432‐ 441. [PMID 25343233]

- ↑ Silkiss RZ, Reier A, Coleman M, Lauer SA. Rituximab for thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(5):310‐314. [PMID 20562667]