Temporal Artery Amyloidosis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Temporal artery involvement in systemic amyloidosis (specifically light-chain (AL) amyloidosis) can mimic vasculitis including giant-cell arteritis (GCA) in the elderly. Patients with amyloidosis may present with GCA like symptoms and signs such as jaw claudication, headache, fatigue, myalgias and sudden vision loss. We compare and contrast systemic amyloidosis and GCA and recommend that clinicians be aware of the differences and similarities between the two entities.

Disease Entity

Disease

Amyloidosis is a systemic or local disorder caused by extracellular deposition of highly ordered fibrils made up of low molecular weight subunits of proteins throughout the body (including the eye and ocular adnexa). The clinical presentation is determined by the specific organ(s) involved by the amyloid deposition include congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. Ocular amyloidosis usually presents as conjunctival lesions and periorbital purpura; however, manifestations have been reported in the adnexa, orbital tissues, retina, vitreous and even the cornea.[1]

Classification

Amyloidosis can be classified based on precursors being produced at the site of deposition (localized amyloidosis) or deriving from circulating products in the blood (systemic amyloidosis). Amyloidosis can further be grouped based on the types of precursors proteins.

Light-Chain (AL) Amyloidosis

Light-chain (AL) amyloidosis, commonly referred as primary amyloidosis, is characterized by deposition of monoclonal light-chain variable-region immunoglobulin fragments. These fragments can involve any tissue or organ. AL is commonly associated with plasma cell dyscrasias (PCD) (e.g., multiple myeloma (MM) and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)).[2]

History

Amyloid depositions in temporal artery biopsies were first described in 1975.[3] In 1986, cases of vascular ischemic symptoms were described due to AL amyloidosis involving the temporal arteries.[4] AL amyloidosis should be in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with vascular ischemic symptoms including GCA. Since then, there have been various reports within the last 30 years documenting amyloidosis affecting the temporal arteries and mimicking the clinical picture of GCA.[5]

Pathophysiology

While deposition of AL amyloid usually occurs in small-caliber vessels, depositions in medium- to larger-sized vessels has also been shown to occur.[2] It has been theorized that these depositions can cause arterial stenosis and narrowing inducing ischemia which could explain AAION in these patients.[6] Similarly, involvement of arterioles that feed the masseter, may cause the jaw claudication often seen in this presentation.[5]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of AL amyloid temporal artery involvement can be accomplished by careful history taking, physical exam, and tissue biopsy. A definitive diagnosis can only be accomplished through a temporal artery biopsy. Clinicians should consider testing for plasma cell dyscrasias (serum protein electrophoresis, serum-free light chains, and immunofixation of blood and urine)[7] if there is clinical suspicion for amyloid. Inflammatory markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) have also been shown to sometimes be elevated in both amyloid and GCA.[6] [8] Biopsies of muscle may be indicated if patients also present with features mimicking polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) with GCA. [9]

Symptoms

Patients with temporal involvement in AL amyloidosis may present with jaw claudication, headache, blurry vision, transient or sudden vision-loss, fatigue, headache and myalgias.[5] Many of these symptoms are not specific and overlap with those of GCA and PMR.

History Taking

AL amyloidosis tends to affect men slightly more than women. In addition, AL presents in older adults, with the mean age of diagnosis of 65 years old.[10] In patients with temporal artery involvement, the mean age was 72 years.[5] Patient history or family history of known or suspected plasma-cell dyscrasias, or hematological malignancy should be noted.

Physical examination

Many ocular signs and symptoms can be observed in patients with temporal involvement in AL amyloidosis, depending on the degree of visual involvement. Upon ophthalmic examination, decreases in visual acuity, visual field defects and relative afferent pupillary defects (RAPD) may present on the affected side. Fundus exam may show a swollen and edematous optic disc, like that seen in arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AAION). Optic disc pallor, hemorrhage and cotton wool spots may also be present.

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age on presentation | 75 | 72 | ||

| Gender | Females > males | Males > females | ||

| Associated symptoms | Jaw claudication, headache, scalp tenderness, myalgia | Similar to GCA; additionally, may present with signs of systemic amyloidosis depending on organ of involvement | ||

| Associated systemic conditions | Polymyalgia rhematica | Plasma cell dyscrasias, Hematological malignancy | ||

| Ophthalmic Exam Findings | Optic disc edema, pallor, hemorrhage, and cotton wool spots | Similar findings to GCA | ||

| Lab findings | Abnormal ESR and CRP | Abnormal ESR and CRP; along with possible detection of precursor proteins and serum-free light chains associated with PSD. | ||

| Response to corticosteroids | Generally improves | Variable |

Adapted from Baig et al. [11]and Ghiani et al. [5]

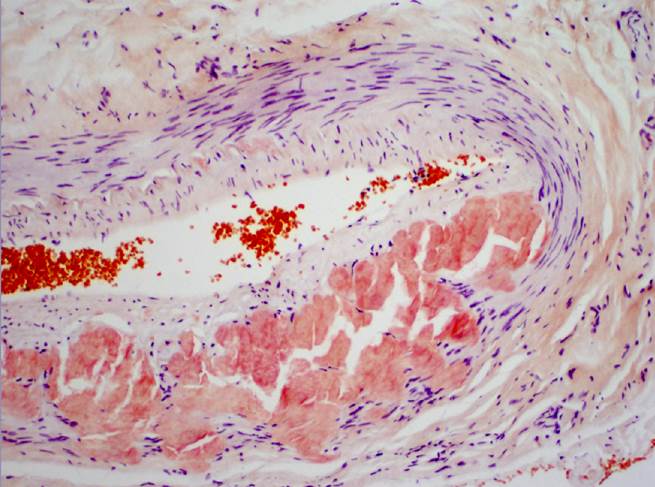

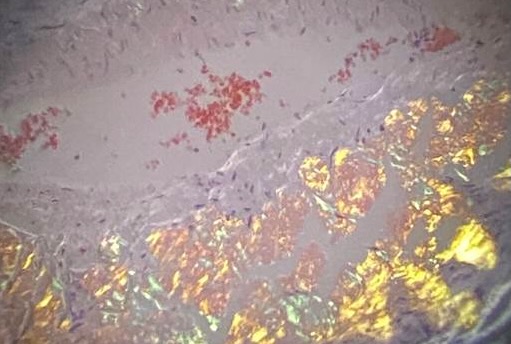

Temporal Artery Biopsy

A temporal artery biopsy (e.g. Congo red and other stains for amyloid) is the definitive way to establish an accurate diagnosis for amyloidosis over GCA. Deposition of amorphous eosinophilic or orangeophilic material can sometimes be present and will produce an apple-green birefringence and dichroism under polarized light (Figures 1 and 2). In a temporal artery biopsy for high suspicion cases for GCA but without vasculitis, amyloid involvement should be considered. Ghinai et al [5] emphasized that an experienced pathologist should re-evaluate reportedly negative biopsies for GCA and that underlying plasma cell dyscrasia should be considered by the clinician in such cases.

Management

It is important to discern between AL amyloidosis and GCA as management of these two conditions are vastly different.[12] Furthermore, delays in diagnosis of AL amyloidosis are not uncommon and this has been shown to play a factor in patient morbidity and mortality.[13] Thus, a patient should promptly follow up with medical oncology and hematology for investigations of an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia and amyloid management following a positive biopsy. Current treatment of AL amyloid is guided based on symptoms, location, severity of organ involvement and clonal characteristics.[14] This can entail passive immunotherapy targeting amyloid deposits, along with chemo and immunotherapy to target amyloid clones.[15] Treatment of AL amyloid can sometimes involve steroids like GCA; however, the regimen may be different. Prolonged steroid treatment may produce side effects and delay diagnosis.[4] Patients with amyloid often show variable response to steroids with some patients improving while others showed either no response or a worsened clinical course.[5]

References

- ↑ Singh RB, Singhal S, Sinha S, et al. Ocular complications of plasma cell dyscrasias. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023;33(5):1786-1800. doi:10.1177/11206721231155974

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Desport E, Bridoux F, Sirac C, et al. Al amyloidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012; 7:54. Published 2012 Aug 21. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-7-54

- ↑ Meretoja J, Tarkkanen A. Amyloid deposits of internal elastic lamina in temporal arteritis. Ophthalmologica. 1975;170(4):337-344. doi:10.1159/000307231

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Gertz MA, Kyle RA, Griffing WL, Hunder GG. Jaw claudication in primary systemic amyloidosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65(3):173-179. doi:10.1097/00005792-198605000-00005

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Ghinai, Rosanna A. M., Mahmood, Shameem, Mukonoweshuro, Pinias, et al. Diagnosing Light Chain Amyloidosis on Temporal Artery Biopsies for Suspected Giant Cell Arteritis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 37(1):p 34-39, March 2017. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000447

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Neri A, Rubino P, Macaluso C, Gandolfi SA. Light-chain amyloidosis mimicking giant cell arteritis in a bilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy case. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013; 13:82. Published 2013 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-13-82

- ↑ Gillmore JD, Wechalekar A, Bird J, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and investigation of AL amyloidosis. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(2):207-218. doi:10.1111/bjh.13156

- ↑ Azarfar A, Sharma A, Parikh JG, Shaikh NM, King-Morris K. Ocular manifestation of giant cell arteritis vs AL-amyloidosis: similar presentations but different approaches. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2021;5(1):117-122. doi:10.1080/24725625.2020.1804662

- ↑ Salvarani C, Cantini F, Hunder GG. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):234-245. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61077-

- ↑ Desport, E., Bridoux, F., Sirac, C. et al. AL Amyloidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7, 54 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-7-54

- ↑ Baig, I. F., Pascoe, A. R., Kini, A., & Lee, A. G. (2019). Giant cell arteritis: early diagnosis is key. Eye and brain, 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2147/EB.S17038

- ↑ Pompilian,V.,Tănăseanu,Ş.,Badea,C.,Zurac,S.,Socoliuc,C.,Badelita,S.,Botez,E. & Antohe,M.(2017).IgG,kappa monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance with AL amyloidosis simulating giant cell arteritis. Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine,55(3) 179-182. https://doi.org/10.1515/rjim-2017-0019

- ↑ Muchtar E, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Treatment of AL Amyloidosis: Mayo Stratification of Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) Consensus Statement 2020 Update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(6):1546-1577. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.03.012

- ↑ Palladini G, Merlini G. How I treat AL amyloidosis. Blood. 2022;139(19):2918-2930. doi:10.1182/blood.2020008737

- ↑ Palladini G, Milani P. Diagnosis and Treatment of AL Amyloidosis. Drugs. 2023;83(3):203-216. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01830-z