Susac Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Microangiopathy of brain, retina, and cochlea (i.e., Susac syndrome (SS)) is a rare condition characterized by the clinical triad of encephalopathy, branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO), and sensorineural hearing loss. However, all three features may not be present concurrently upon initial presentation. This condition may also be referred as small infarctions of cochlear, retinal, and encephalic tissue (SICRET), microangiopathy with retinopathy, encephalopathy, and deafness (RED-M), and retinocochleocerebral vasculopathy.[1][2]

Etiology & pathophysiology

SS is a presumed to be caused by autoimmune endotheliopathy , resulting in microinfarcts of the precapillary arterioles of the brain, retina, and inner ear (cochlea and semicircular canals).[2][3] The exact mechanism is unclear, but pathogenesis does resemble the microinfarction of muscle and skin seen in juvenile dermatomyositis. New studies have suggested that anti-endothelial cell antibodies (AECAs) may be involved since biopsy findings in SS reveal endothelial cell necrosis, which is associated with AECAs. AECAs have been hypothesized to mediate thrombotic depositions in the vessels, though preference for the arterioles of the brain, retina, and inner ear seen in SS is unclear.[2][4] SS can be categorized into three clinical courses: monocyclic, polycyclic, and chronic continuous. Monocyclic courses are acute and self-limiting within two years without recurrence. The polycyclic course requires remission followed by relapses occurring beyond two years, and chronic continuous course never has a clear remission.[2]

Epidemiology

SS has a slight female predominance and typically affects those aged 16-40 years, with extremes ranging from 7 to 72 years[5]. Of the reported cases, most patients are white individuals from North America and Europe. There has also been a small number of cases diagnosed during pregnancy and post-partum period.[1]. Radiologic interpretation is variable therefore recognition is sometimes suboptimal.

Diagnosis

Signs & symptoms

On initial presentation, the clinical triad of SS does not often present collectively and has an average delay between presenting symptoms and complete triad being approximately 5 months. Symptoms of CNS dysfunction are the most common initial manifestation, followed by visual, then vestibulocochlear symptoms. Migraine-like headaches are also common and are present in 80% of reported cases. These headaches may precede presenting symptoms by several months. Complete triad on initial presentation only occurred in 13% of 304 reported cases and was more common in monocyclic cases.[1] Though CNS dysfunction symptoms will vary, symptoms of encephalopathy will predominate. These include migraine-like headache, cognitive impairment, confusion, emotional disturbance, behavioral or personality changes, apathy, psychosis, and reduction of vigilance.[6] Other symptoms of CNS dysfunction include ataxia, vertigo, gait abnormality, sensory disturbance, upper motor neuron signs, paresis, nausea and vomiting, dysarthria, oculomotor dysfunction, urinary dysfunction, and diplopia.[1] In general however, if no encephalopathy presents within the 2years of BRAO/vestibular dysfunction, it is unlikely develop encephalopathy.

Visual manifestations include blurriness, flashes, and visual field defects.[1][2]

Vestibulocochlear manifestations typically involve bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, though unilateral hearing loss may also occur. Patients may also complain of tinnitus and vertigo with associated severe hearing loss.[2][3]

Physical exam

Physical exam should include a full neurological and standard 8-point ophthalmic exam, which may reveal findings as listed above. Visual field defects may be detected, and a fundus exam may range from normal findings, to subtle arteriolar wall hyperfluorescence (AWH), to obvious BRAO. [1][3]

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for SS includes, but is not limited to, multiple sclerosis, various vasculidities, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) as these are common misdiagnoses. However, absence of oligoclonal bands can help to differentiate SS from multiple sclerosis.[1][2]

Diagnostic studies

Workup for SS includes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), retinal fluorescein angiography (FA), and audiogram.[1][2][3] Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) has also shown to assist diagnosis in the later stage of SS when OCT and FA can no longer detect BRAO and AWH.[7]

In the acute phase of SS, T2-weighted MRI will reveal supratentorial white matter lesions, particularly in the central corpus callosum. A “snowball lesion” in the corpus callosum is a characteristic sign of the microinfarcts. As the disease progresses, T1 MRI may reveal brain atrophy and callosal holes, icicle and spokes configuration, and thinning.[2][3][8] MRI may also reveal microinfarcts of the corpus callosum in a string-of-pearls configuration if long-tract symptoms are present. Leptomeningeal enhancement and deep grey matter and cortical involvement may also be present and can distinguish this disease from MS or ADEM.[3] (For imaging cases review, see Additional Resources)

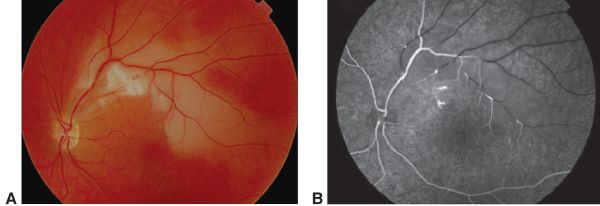

When SS is suspected, FA and audiograms could assist in diagnosis to identify BRAO and sensorineural hearing loss, respectively, even if patients appear asymptomatic. Audiograms will typically reveal bilateral low to middle frequency hearing loss.[1][2] During the acute phase of SS, FA may reveal BRAO and/or multifocal AWH.2,3 Gass plaques, which appear as small yellow dots in retinal arteriole walls between bifurcations, may also be detected.[2] An example can be seen in Figure 1. SD-OCT has also been proposed as a complementary method to detect the long-term sequelae effects. Patchy thinning from the retinal nerve fiber layer to the outer plexiform layer, particularly in the temporal quadrants, with sparing of the outer nuclear and photoreceptor layers will be present. These findings are consistent with layers affected by the retinal, and not choroidal, arteries.[7]

Cerebral spinal fluid analysis in SS may reveal unspecific elevated total protein with mild lymphocytic pleocytosis. The presence of oligoclonal bands can help to differentiate SS from multiple sclerosis. EEG can be done to identify the presence of encephalopathy.[1][2] Other tests, such as autoantibodies and clotting abnormalities screening, cerebral catheter angiography, and leptomeningeal biopsy have shown to provide little use in the diagnosis of SS.[1]

Management

Medical therapy

As there is a lack of extensive evidence-based research on this rare disease, management is based on expert recommendations and proposed similarity in pathogenesis to juvenile dermatomyositis. Early and aggressive immunosuppressive treatment has been shown to be important in preventing future relapses, delay disease progression and prevent complete deafness, blindness and dementia[9]. Treatment should not be delayed awaiting presence of complete clinical triad.[1][8] Treatment in the acute period may include high-dose glucocorticosteroids with a fast-onset immunosuppressive drug, such as cyclophosphamide or rituximab to prevent additional attacks and disease progression. IVIG and plasmapheresis may also be a beneficial adjunct. Maintenance therapy is then initiated for around 2 years following clinical improvement and involves a slow tapering of corticosteroids at 2-4 week intervals and transition to immunosuppressive drugs with lower risk long-term side effects, including mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and azathioprine. Monitoring with routine brain MRI and FA for relapse during remission is crucial prior to stopping treatment. Those with recurrent BRAO are often self-limiting and only close monitoring is recommended. Hearing aids and cochlear implants can be offered to improve quality of life for those left with hearing loss. There has also been discussion about the use antiplatelets and nimodipine, but these have not been shown to be beneficial.[8]

Prognosis

Prognosis for SS is generally favorable with CNS and visual symptoms typically resolving with some compensation. However, hearing loss may be permanent, and in rare cases the neurological effects of SS can progress to dementia.[2][3]

In a small case series the authors found that retinal collaterals can be present after long term follow up in patients with BRAO in Susac disease, they are usually arterio-arterial (A-A) collaterals and rarely arterio-venous (A-V) collaterals and are suspected to arise secondary to the influence of chronic inflammation[10]

Additional Resources

-Susac syndrome. Last revised by Rohit Sharma on 28 May 2023 at Radiopaedia: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/susac-syndrome?lang=us

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Dörr J, Krautwald S, Wildemann B, et al. Characteristics of Susac syndrome: a review of all reported cases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(6):307-316. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.82

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Greco A, De Virgilio A, Gallo A, et al. Susac’s syndrome — Pathogenesis, clinical variants and treatment approaches. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(8):814-821. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.04.004

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Rennebohm R, Susac JO, Egan RA, Daroff RB. Susac’s Syndrome — Update. J Neurol Sci. 2010;299:86-91. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.032

- ↑ Jarius S, Kleffner I, Dörr JM, Sastre-Garriga J, Illes Z, Eggenberger E, Chalk C, Ringelstein M, Aktas O, Montalban X, Fechner K, Stöcker W, Ringelstein EB, Paul F, Wildemann B. Clinical, paraclinical and serological findings in Susac syndrome: an international multicenter study. J Neuroinflammation. 2014 Mar 8;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-46. PMID: 24606999; PMCID: PMC3995917

- ↑ Egan, Robert A. MD; Brown, Adam MD; Grillo, Eugenio MD. Early Presentation of Susac Syndrome in a 7 Year Old. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology ():10.1097/WNO.0000000000001487, July 12, 2022. | DOI: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001487

- ↑ Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979 Mar;29(3):313-6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.29.3.313. PMID: 571975

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Ringelstein M, Albrecht P, Kleffner I, et al. Retinal pathology in Susac syndrome detected by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Neurology. 2015;85(7):610-618.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 8.2 Vodopivec I, Prasad S. Treatment of Susac Syndrome. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016. doi:10.1007/s11940-015-0386-x

- ↑ Sauma J, Rivera D, Wu A, et al. Susac's syndrome: an update. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020;104(9):1190-1195. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315597

- ↑ Egan, Robert A. MD; Jirawuthiworavong, Guy MD; Lincoff, Norah S. MD; Chen, John J. MD, PhD; Francis, Courtney E. MD; Leavitt, Jacqueline A. MD Retinal Arterio-Arterial Collaterals in Susac Syndrome, Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology: December 2018 - Volume 38 - Issue 4 - p 459-461 doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000627