Surgically-Induced Necrotizing Scleritis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Surgically Induced Necrotizing Scleritis (SINS) is characterized by necrotizing scleritis following multiple ocular procedures. This most often occurs after multiple ocular surgeries and is believed to be a type IV hypersensitivity reaction.[1]

Other terms for this disease process include surgically-induced scleral necrosis, postoperative scleral melting, postsurgical necrotizing scleritis, postsurgical scleral necrosis, postoperative scleral necrosis, postoperative necrotizing scleritis, and autoimmune SINS.

Disease Entity

Etiology/Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis remains unclear, but SINS is believed to be a delayed type of hypersensitivity response to scleral tissue antigens that are altered or exposed due to surgery.[1] Pathologic studies have shown IgM and IgG deposition, increased HLA-DR expression, and T-helper cell participation in conjunctival biopsies.[2] There is also a strong association of systemic autoimmune disease with SINS, with multiple studies that reveal underlying systemic disease upon further workup after SINS.[1][3] This suggests that there was underlying subclinical autoimmunity that was accelerated due to surgical trauma. For cases of SINS that manifest years after surgery, it is more likely that the immune response is triggered elsewhere and later manifests in the eye.[1]

There also seems to be an association between SINS and cases which use adjunctive beta-radiation or anti-metabolites such as mitomycin C, as one study reports 82% of SINS following pterygium surgery was associated with this use.[4] Although this may suggest that localized ischemia could be the cause of SINS, this likely does not encompass the entire process as the normal sclera is fairly avascular. SINS is more likely explained by the enzymatic degradation of scleral collagen following surgical manipulation and epithelial destruction.[4]

Risk Factors

Patients with connective tissue disease are at higher risk of developing SINS post-operatively. This is believed to be due to systemic vasculitis associated with collagenases, which affect the blood vessels of the deep episcleral venous plexus. Other risk factors include the female gender, other autoimmune diseases, and prior ocular surgeries.[1]

Ocular surgeries that have been associated with SINS include cataract extraction, trabeculectomies, strabismus corrective procedures, scleral buckles, pars plana vitrectomies, and pterygium surgeries.[1][4][5] Ocular surgeries that use mitomycin C, such as cosmetic conjunctivectomy, are also higher risk.[6] SINS can also develop after secondary postoperative minor procedures such as suture removal, yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser capsulotomy, or wound leak repair.[1]

Presentation/Diagnosis

Presentation

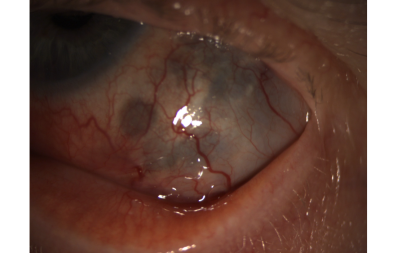

SINS usually presents as inflammation and necrosis of the tissue adjacent to the surgical wound after ocular surgery, often with a delay in presentation from the time of surgery. The average time to SINS onset from time of surgery is 9 months, though timing can be widely variable with the longest reported interval being 51 years post-surgery.[1][7] In cases with severe or chronic necrotizing inflammation, uveal show and/or prolapse may be present as well. Necrotizing keratitis may also be present.[1] Symptoms of SINS can include redness, tearing, tenderness, and pain with extraocular movement.[8] Decreased vision may also be present in cases with corneal involvement. In some cases, the inflammation can extend posteriorly and cause posterior scleritis as well.[1]

Clinical Diagnosis

SINS is a clinical diagnosis based on history and clinical examination, though infectious causes must be ruled out. However, laboratory testing is often necessary to discover any associated connective tissue and autoimmune disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Infectious scleritis

Infectious scleritis is most commonly bacterial, with Pseudomonas spp, responsible for up to 85% of cases of infectious scleritis, and often occurs after accidental or surgical trauma.[9] Other bacteria that have been commonly isolated include Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae.8 Viral scleritis, frequently caused by Varicella zoster virus or Herpes simplex virus, often presents with corneal inflammation and hypoesthesia in addition to scleritis .[10] Fungal scleritis, most commonly caused by Aspergillus flavus in tropical and developing countries , is the most severe type of infectious scleritis; it is much harder to control due to poor penetration of antifungals and can more likely progress to globe destruction .[10] Although some suggest that SINS can be caused by primary[11] or predisposed to secondary infection,[12] SINS is still considered a diagnosis of exclusion that is distinct from infectious causes.

Autoimmune necrotizing scleritis

Autoimmune necrotizing scleritis is very similar to SINS, except that autoimmune necrotizing scleritis is more commonly bilateral and does not necessarily have a history of ocular surgery. In cases where there is a history of multiple ocular surgeries with occurrence of scleritis at the surgical site, the diagnosis of SINS is favored.

Management

Medical Therapy

It is critical that infectious etiology is ruled out prior to starting anti-inflammatory therapies for SINS. NSAIDs are not recommended as first-line treatment in SINS. High dose systemic steroid therapy such as oral prednisone, with or without topical prednisolone, is the treatment option of choice for acute SINS and is sufficient to manage most cases.[1][13] Patients may also receive a pulse of intravenous methylprednisolone for particularly severe acute inflammation.[1] In refractory cases, switching to immunomodulatory therapy such as azathioprine or cyclophosphamide is often required to control the inflammation and reduce the harmful effects of long-term systemic steroid use.[1]

In a few cases where SINS progresses despite medical therapy and causes severe scleral melt, surgical intervention such as tectonic lamellar keratoplasty may be indicated. [14] Perforation through necrotic sclera necessitates surgical excision of necrotic tissue and tectonic reconstruction using corneoscleral, scleral, or corneal patch grafts.[1]

Prognosis

Earlier medical intervention is associated with better visual outcomes and avoidance of adverse outcomes such as staphyloma and scleral melting.[15] Patients who are started on high-dose steroids within the first month of presentation lose on average 1-3 lines on Snellen visual acuity, whereas patients who are treated after 3 months have been shown to permanently lose 5 lines or more on Snellen visual acuity.[1] Patients with a history of SINS can be given perioperative pulsed methylprednisolone to protect against recurrence. Reactivation of SINS requiring therapy can occur anywhere from immediately after the acute stage to years after remission from treatment.[1]

Conclusion

SINS is a rare complication following multiple ocular surgeries that is believed to be due to an autoimmune process. SINS presents more often in patients with concomitant autoimmunity, so a thorough workup for other autoimmune processes may be warranted. By quickly identifying the diagnosis and excluding infectious etiologies, SINS can often be managed using immunosuppressants with good visual outcomes and minimal adverse effects.

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 O’Donoghue E, Lightman S, Tuft S, Watson P. Surgically induced necrotising sclerokeratitis (SINS)--precipitating factors and response to treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(1):17-21.

- ↑ Díaz-Valle D, del Castillo JMB, Castillo A, Sayagués O, Bañares A, García-Sánchez J. Immunologic and Clinical Evaluation of Postsurgical Necrotizing Sclerocorneal Ulceration. Cornea. 1998;17(4):371.

- ↑ Sainz de la Maza M, Foster CS. Necrotizing scleritis after ocular surgery. A clinicopathologic study. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(11):1720-1726. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32062-1

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Doshi RR, Harocopos GJ, Schwab IR, Cunningham ET. The spectrum of postoperative scleral necrosis. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2013;58(6):620-633. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.11.002

- ↑ Pujari A, Chaniyara MH, Sharma P, Sharma N. Necrotizing scleritis following uncomplicated strabismus surgery. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Nov;68(11):2555-2557. doi: 10.4103/ijo.

- ↑ Ji YW, Park SY, Jung JW, et al. Necrotizing Scleritis After Cosmetic Conjunctivectomy With Mitomycin C. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2018;194:72-81. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.008

- ↑ Mahmood S, Suresh PS, Carley F, Bruce IN, Tullo AB. Surgically induced necrotising scleritis: report of a case presenting 51 years following strabismus surgery. Eye. 2002;16(4):503-504. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6700033

- ↑ Lagina A, Ramphul K. Scleritis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed October 23, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499944/

- ↑ Moshirfar M, Ronquillo Y. Infectious Scleritis. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed October 23, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560818/

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 Murthy SI, Sabhapandit S, Balamurugan S, et al. Scleritis: Differentiating infectious from non-infectious entities. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(9):1818-1828. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_2032_20

- ↑ Rich RM, Smiddy WE, Davis JL. Infectious Scleritis after Retinal Surgery. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;145(4):695-699. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2007.11.024

- ↑ Vagefi MR, Hollander DA, Seitzman GD, Margolis TP. Bilateral surgically induced necrotising scleritis with secondary superinfection. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005;89(1):124-125. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.051359

- ↑ Madanagopalan VG, Shivananda N, Krishnan T. Surgically induced necrotizing scleritis after retinal detachment surgery masquerading as scleral abscess. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2019;9:Doc18. Published 2019 May 29. doi:10.3205/oc000107

- ↑ Ti SE, Tan DTH. Tectonic corneal lamellar grafting for severe scleral melting after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1126-1136. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00260-4

- ↑ Das S, Saurabh K, Biswas J. Postoperative Necrotizing Scleritis: A Report of Four Cases. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014;21(4):350-353. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.142277