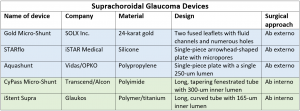

Suprachoroidal Devices

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

The uveoscleral outflow pathway was first described in animal experiments by Anders Bill in 1965.[1] [2] Aqueous exits the anterior chamber (AC) across the ciliary body and iris root, driven by the negative pressure gradient from the AC to the suprachoroidal space.[3] From there, fluid is resorbed into scleral vessels, the choriocapillaris, and through scleral pores into the episclera.[4] Prostaglandin analogues, commonly prescribed as first-line medical therapy for glaucoma, increase aqueous outflow through this uveoscleral pathway, thereby lowering intraocular pressure.[5]

Surgical access to the suprachoroidal space to lower intraocular pressure in patients with glaucoma is not a novel concept. Surgical creation of a cyclodialysis cleft to lower intraocular pressure was described by Heine in 1905 for intractable glaucoma;[6] However, this procedure was largely abandoned due to frequent postoperative hypotony and a rapid increase in intraocular pressure after spontaneous closure of the cleft. Various techniques, implants, and space-maintaining substances have been described in an attempt to create a safer and more stable suprachoroidal drainage pathway, with limited success.[7] [8] [9] [10] [11]

With advances in device design and biocompatibility, the uveoscleral outflow pathway is again a target of active research and development. Several new microsurgical devices seek to lower intraocular pressure by exploiting the outflow facility of the suprachoroidal space and providing a controlled and sustainable fluid egress from the anterior chamber. Both ab externo and ab interno approaches to the suprachoroidal space are possible, each with unique advantages and drawbacks.

Ab Externo Approach

The suprachoroidal space can be accessed ab externo via a trans-scleral dissection. This approach has the disadvantage of requiring both conjunctival and scleral manipulation, which may make additional glaucoma filtering surgery difficult in the future due to scarring. However, an ab externo approach may allow for more extensive tissue dissection and potentially greater IOP lowering compared to an ab interno approach. Three notable ab externo devices include The Gold Micro-Shunt (GMS, SOLX Corp, Waltham, MA), the STARflo (iStar Medical, Isnes, Belgium), and the Aquashunt (OPKO Health, Miami, FL).

Gold Micro-Shunt

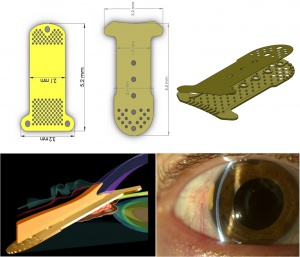

Design

The GMS is made of medical-grade 24-karat gold. The concept for this device was based on the observation that a gold foreign body was well tolerated in the eye.[12] The original GMS is 3.2 mm wide, 5.2 mm long, 44 um thick, and weighs 6.2 mg. The shunt is composed of two rectangular fused leaflets with a rounded proximal end, and a distal end with fins to anchor the device in the suprachoroidal space. The proximal end of the shunt has sixty 100-um holes and one 300-um hole to allow aqueous to enter. The distal end contains a grid of 117 110-um holes on each side of the implant to allow free flow of fluid into the suprachoroidal space. Nineteen channels are present within the shunt of which 9 are open, each with a width of 24 um and a height of 50 um. The GMS+, a revised model, is 3.2 mm wide and 5.5 mm long and weighs 9.2 mg. The design has been modified such that the fins are located at the proximal end of the device in the anterior chamber. The external gold plates of the GMS+ are separated by posts rather than channels, creating a larger area of aqueous flow (Figure 1). The GMS was approved for use in Canada, as well as in some European countries. In the U.S., the GMS had a high failure rate in investigational studies, and FDA approval was never granted.[13]

Surgical Technique

Following the creation of a fornix-based conjunctival flap, a full-thickness scleral incision is made 2-3 mm posterior to the limbus, exposing the suprachoroidal space. The anterior chamber is deepened using either viscoelastic or an anterior chamber maintainer. A crescent blade is then used to tunnel anteriorly into the AC at approximately 90% scleral thickness. Blunt dissection is also directed posteriorly into the suprachoroidal space. The proximal end of the GMS is fed into the anterior chamber using the inserter which comes with the device, such that 1-1.5 mm of the device is visible in the AC. The distal portion of the shunt is then tucked underneath the posterior lip of the scleral flap. The scleral and conjunctival flaps are then closed tightly to avoid leakage of aqueous and bleb formation.

Clinical Results

Skaat et al[14] compared two different models of the GMS (24-um internal channels or 48-um internal channels) with the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve in a three-armed randomized, prospective, interventional trial for patients with refractory glaucoma. All patients included in the study had either primary open-angle glaucoma, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, or pigment dispersion glaucoma and had undergone at least one failed trabeculectomy. Twenty-nine patients were randomized for implantation with either an Ahmed glaucoma valve, 24-um GMS or 48-um GMS. Success was defined as IOP greater than 5 mmHg and less than 22 mmHg with a reduction of IOP at least 20% below preoperative IOP. IOP was significantly lowered in all 3 groups after 5 years of follow-up. In the Ahmed group, IOP was lowered from 33.5±6.7 to 17.3±2.6 mm Hg. In the 24-um GMS group, IOP was lowered from 25.7±0.7 to 17.8±2.4 mm Hg. In the 48-um GMS group, IOP was lowered from 35.6±2.2 to 19.6±5.2 mm Hg. The number of glaucoma medications required was not significantly different between groups. Cumulative success rates at 5 years were 77.8%, 77.8%, and 72.7% in the Ahmed, 24-um GMS, and 48-um GMS, respectively.

Hueber et al[15] reported very different results in a retrospective review of 31 eyes which were implanted with the second-generation GMS+. The patients in this study were diverse; 48% of eyes had undergone previous glaucoma surgery, 55% had primary open-angle glaucoma, 16% had pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, 13% had secondary glaucoma, 10% had pseudophakic angle closure glaucoma, and 6% had pigmentary glaucoma. Failure was defined as IOP greater than 21 or less than 5 at any visit at least 6 months after GMS+ implantation, any serious complications (retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, suprachoroidal hemorrhage, low-grade inflammation, or new-onset rubeosis iridis) or need for additional glaucoma surgery. At the end of 4 years, 97% of eyes met criteria for failure, with 71% of eyes failing within the first year. 77% of eyes required a secondary glaucoma surgery for uncontrolled IOP, with mean time to second surgery 7.3 months (range 0.5-37.1). Two GMS+ were explanted because of newly developed rubeosis iridis, and two were explanted for persistent low-grade inflammation. At the conclusion of the study, mean IOP for all patients was 27.9±10.4 mmHg, slightly increased from the preoperative mean IOP of 26.58 ± 10.14 mmHg. No definitive rationale for the poor performance of the GMS in this study was provided by the authors.

Figus et al[16] reported on 55 eyes of 55 patients with refractory glaucoma. All patients had uncontrolled IOP on maximum tolerated medical therapy and had undergone at least 1 previous glaucoma surgery (range 1-5). Patients underwent GMS implantation and were followed for two years. Success was defined by IOP less than 21 mmHg and >33% IOP reduction. At 2 years, 67.3% of patients were considered a qualified success, while only 5.5% were considered a complete success. The most common complication was transient hyphema (21.8%). Choroidal detachment was noted in 10.9% of eyes. Explantation was required in three eyes (5.45%): two secondary to corneal edema due to endothelial-shunt contact and one secondary to over-filtration causing exudative retinal detachment. Most failures occurred within the first year. The most common cause of failure was an inflammatory membrane forming on the anterior end of the shunt, obstructing inflow from the AC (66.6%).

STARflo

Design

The STARflo is made of a proprietary flexible, micro-porous medical grade silicone called STAR Biomaterial, which is designed to optimize tissue integration and reduce fibrosis. It is a single piece porous implant with 3 parts: a head, neck and body. The STARflo device received CE marking approval in Europe in 2012.

Surgical Technique

A conjunctival flap is created followed by a partial-thickness scleral flap. The head is implanted in the anterior chamber at the anterior aspect of the scleral flap, and a full-thickness scleral incision is made at the posterior edge of the flap to allow the body to be inserted into the suprachoroidal space. The scleral and conjunctival flaps are sutured tightly to avoid leakage of aqueous and bleb formation.

Clinical Results

In an early clinical trial[17] [18], 4 patients had the STARflo device implanted. Three patients completed 12-month follow up and 1 was removed from the study after undergoing cyclophotocoagulation 4.5 months postoperatively for uncontrolled IOP. In those completing the study, mean IOP was 14.5 mmHg after 12 months compared to 37.0 mmHg preoperatively. IOP was reduced to less than 21 mmHg and by more than 30% from baseline in all patients completing follow up. Early postoperative complications included bleb formation, hypotony, choroidal hemorrhage and abnormal macula.

A prospective clinical trial was performed at a single center in Europe.[19] In this study, the STARflo glaucoma implant was placed in 40 eyes in 32 patients with treatment-refractory, moderate to severe open-angle glaucoma. After 24 months, 45% of treated eyes in the study required an additional glaucoma procedure, while 55% of patients saw a decrease in the average number of topical ocular hypotensive medications from 2.7 pre-operatively to 1.2 at 24 months. Unfortunately, the study failed to demonstrate effective IOP reduction at 24 months. Additionally, many patients exhibited decreased endothelial cell counts, with corneal decompensation occurring in 5 eyes (12.5%).

Aquashunt

Design

The Aquashunt was originally designed by Vidus Ocular, a start up led by Dr. Bruce Shields at Yale University. After initial pre-clinical trials, Vidus was purchased by OPKO Health (Miami, FL). The Aquashunt is made of polypropylene and is 4 mm wide, 10 mm long, and 0.75 mm thick. It has a single 250-micron lumen.

Surgical Technique

After creation of a conjunctival flap, a full-thickness scleral incision is made to expose the suprachoroidal space. The shunt is advanced through the suprachoroidal space using a custom inserter, breaking attachments between the ciliary body and the scleral spur to enter the anterior chamber. The distal end of the device is tucked underneath the sclera, posterior to the scleral incision and the device is sutured to the sclera in order to secure its position. The scleral and conjunctival flaps are then closed tightly to prevent leakage of aqueous and bleb formation.

Clinical Results

In 2009, OPKO Health funded a clinical trial of the Aquashunt in the Dominican Republic. The results of this trial were not published. Reportedly, there were mixed results after implantation in the first 15 patients with refractory open-angle glaucoma. After 12 months, 1 device was explanted, 3 patients did not achieve adequate IOP lowering, 3 patients developed hypotony, and 8 patients achieved an average IOP reduction of 31% (range 13-46%).[20] OPKO Health decided not to pursue clinical trials in the United States, and the intellectual property license was transferred back to Yale University. Currently there are no ongoing clinical trials investigating the Aquashunt.

Ab Interno Approach

The suprachoroidal space can also be accessed through an ab interno approach using a clear corneal incision and intraoperative gonioscopy. This approach seeks to provide increased outflow via the suprachoroidal space without manipulation of the conjunctiva and sclera. The main advantages of this approach are the relatively simple, straightforward insertion of devices and avoidance of conjunctival manipulation to allow for traditional bleb-based filtering surgery, if needed later in the future. Three ab interno devices are the Cypass Micro-Stent (Alcon, Inc), iStent Suprachoroidal Bypass System (iStent Supra, Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA), and the MINIject (iSTAR Medical SA, Wavre, Belgium).

Cypass Micro-Stent

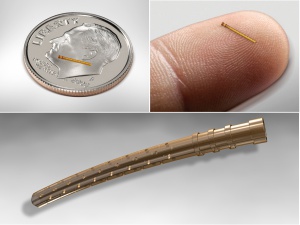

Design

The Cypass Micro-Stent is a 6.35 mm long polyimide tube with an outer diameter of 0.5 mm and an inner diameter of 300 um. It has fenestrations to facilitate outflow along the entire length of the device (Figure 2). Initial foundations for design of the Cypass device have been described.[21]

Surgical Technique

The Cypass Micro-Stent can be inserted through a clear corneal incision combined with cataract extraction or as a stand-alone procedure. The anterior chamber is deepened using viscoelastic, and intraoperative gonioscopy is used to visualize angle structures. The stent is positioned on a guide-wire which is passed across the anterior chamber and used to bluntly dissect the ciliary body from the scleral spur, effectively creating a miniature cyclodialysis. The device is then passed along the guide-wire into the suprachoroidal space, with the proximal collar of the device remaining in the anterior chamber. The guide-wire is withdrawn once appropriate position is verified. Anterior segment OCT or ultrasound biomicroscopy can be used to verify the position of the stent postoperatively.[22]

Clinical Results

Feijoo et al[23] followed 65 eyes of patients with open angle glaucoma and IOP >21 on medical therapy which were treated with Cypass micro-shunt implantation through a clear corneal incision. Cypass implantation was not combined with cataract extraction in this study. IOP was reduced from 24.5±2.8 to 16.4 ±5.5 mmHg at 12 months (n=55). Mean medication usage was decreased from 2.2±1.1 at baseline to 1.4±1.3 at 12 months. The most common adverse events were IOP>30 beyond 1 month (11%), transient hyphema (6%) and progression of cataracts (12%). No serious complications such as retinal detachment, choroidal effusion, persistent uveitis, persistent hyphema or hypotony maculopathy were observed. Secondary glaucoma surgery was required in 17% of eyes during the 1-year follow up.

Hoeh et al[24] prospectively studied 167 eyes of 142 patients with open angle glaucoma and cataract. Patients underwent combined phacoemulsification with posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) placement and Cypass micro-shunt placement. Analysis was divided into two cohorts. Cohort 1 (n=65) had baseline IOP ≥21 mmHg, and Cohort 2 (n=102) had baseline IOP <21. Mean follow up was 294±121 days. Cohort 1 demonstrated a 35% reduction in mean IOP and 49% reduction in mean medication usage. Cohort 2 demonstrated 75% reduction in mean medication use, and maintained IOP <21 in all eyes. Overall, mean IOP at 12 months was 15.9±3.1 mmHg compared to 20.2±6.0 mmHg preoperatively. No serious complications or adverse events were observed. Early postoperative IOP elevation occurred in 1.2% of eyes, and late IOP elevation in 1.8% of eyes. Two patients developed transient hyphema.

In another study by Hoh et al[25], patients with cataract and open-angle glaucoma were included in a prospective consecutive case series. All patients underwent combined phacoemulsification with posterior chamber IOL placement and Cypass Micro-Stent implantation. Analysis was divided into two cohorts. Cohort 1 (n=23) had baseline IOP ≥21, and Cohort 2 (n=59) had baseline IOP <21. After 24 months, Cohort 1 had a mean IOP of 15.8±3.8 mmHg, a 37±19% reduction from baseline. IOP reduction in Cohort 1 was statistically significant at 6, 12, and 24 months. For cohort 2, mean IOP at 24 months was 16.1±3.2 mmHg, a 0±28% change from baseline. Mean glaucoma medications were reduced from 2.2 at baseline to 1.0 at last follow-up in Cohort 1 and from 2.0 to 1.1 in Cohort 2 at 24 months. Mean decrease in glaucoma medications from baseline was statistically significant at 6, 12 and 24 months in both cohorts. With regard to complications, 15.4% of patients experienced transient hypotony and 8.8% of patients developed micro-stent obstruction due to iris overgrowth. Secondary incisional glaucoma surgery was required in 11% of patients during the 2-year follow up.

The COMPASS trial is a large FDA-approved randomized controlled trial in which 505 patients were been enrolled at 27 sites to receive either Cypass Micro-Stent implantation combined with cataract surgery or cataract surgery alone. The COMPASS trial found higher IOP-lowering efficacy in patients randomized to the Cypass Micro-Stent compared to cataract surgery alone. However, a post-approval study with a follow-up of 5 years found a statistically significant difference in corneal endothelial cell density in patients randomized to the Cypass Micro-Stent compared to cataract surgery alone, with one patient receiving the Cypass Micro-Stent experiencing corneal edema. The number of Cypass retention rings extending into the anterior chamber was independently and negatively associated with corneal endothelial cell density. As a result of findings from this post-approval study, the Cypass Micro-Stent was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in August 2018.

Bio-interventional Cyclodialysis with Allograft Scleral Reinforcement

Design

The bio-scaffolded cyclodialysis is different from suprachoroidal devices whereby the endogenous cyclodialysis serves as the primary filtration conduit to the uveoscleral pathway. The biotissue if for structural reinforcement of the cleft. Unlike the suprachoroidal devices where the exogenous implantable hardware is the primary filtration mechanism.

Bio-interventional techniques are now emerging using bio-tissue (Clin Ophthalmol 2024 Jun 21:18:1789-1795). A bio-compatible tissue may be placed in the supraciliary space to reinforcement the cleft opening. Donor allograft has long been used for homologous scleral reinforcement in glaucoma surgery to cover and fixate the tubes of glaucoma drainage devices to the scleral wall. The acellular, sterile donor tissue is readily available, bio-compatible and has long-term durability and structural stability. It also comes sterilized and has a long shelf life.

Surgical Technique

The surgery is a two-step multi-interventional procedure starting with the creation of an ab-interno cyclodialysis (1-2 clock hours). Then, minimally manipulated, micro-trephined bio-interventional allograft is deployed within the cleft to reinforce the filtration conduit at the endoscleral wall and prevent restenosis. The flexible tissue (5mm length x 500-micron width) is fully deployed within the cleft in a non-protruding AC-clear position to eliminate any potential negative impact in the anterior chamber or on the cornea. The technique allows the surgeon to create uveoscleral outflow channel of one or several clock hours with single or multiple bio-tissue spacers. The surgical technique is performed with the CycloPen™ cyclodialysis instrumentation and the AlloFlo™ bio-tissue by Iantrek, Inc.

Clinical Results

Surgical outcomes in 243 cases were reported in the J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13(16), 4593; https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164593 demonstrating the feasibility of this multi-step intervention as well as the intraoperative and post-operative safety - there were few adverse events which were self-limited and transient. Long-term results were reported at the American Academy of Ophthalmology 2023 meeting by Sheybani et al. At 12 months, the mean medicated intraocular pressure (IOP) decreased by 27.1% from baseline, with hypertensive eyes (baseline medicated IOP > 21 mmHg) showing a 39.7% reduction. Additionally, 81.9% of all eyes achieved a medicated IOP ≤18 mmHg without an increase in ocular hypotensive medications. A large prospective real-world clinical study of close to 400 patients is ongoing in the United States

MINIject drainage system

Design

The MINIject glaucoma drainage device (iSTAR Medical SA, Wavre, Belgium) is a novel supraciliary minimally invasive soft flexible silicone implant designed to target the suprachoroidal space. It is 5 mm in length with an oblong cross-sectional design measuring 1.1×0.6 mm. A green ring positioned at 0.5 mm from the tip of the device allows for accurate positioning and indicates the proper depth of placement.

It is composed of a biocompatible porous proprietary silicone (STAR®) material that provides minimal tissue reaction and theoretically reduces the risk of fibrosis. The unique flexible design conforms to the shape of the eye. The micropores are arranged in a network of hollow spheres.

Surgical Technique

The MINIject can be inserted ab-interno into the suprachoroidal space as a stand-alone procedure through a 2-mm clear corneal incision. The device is then gently advanced between scleral spur and ciliary body until the green-colored ring at the proximal end of the device at the level of scleral spur. When the middle of the ring is at the level of the scleral spur, only 0.5 mm of the device projects in the anterior chamber. The delivery system is then activated, retracting the sheath while leaving the implant in the suprachoroidal space.

Clinical Results

The safety, efficacy, and adverse effects of the MINIject in glaucoma management were first evaluated by Denis and colleagues[26] as a stand-alone procedure in a multicentre, prospective, single-arm trial. The study was conducted at 2 different institutes in India and Panama. The study included 25 eyes of uncontrolled open-angle glaucoma patients. The mean IOP was significantly reduced from a baseline of 23.2±0.6 mmHg on a mean of 2.0±1.1 glaucoma medications to a mean of 14.2±0.9 mmHg on a mean of 0.3±0.7 glaucoma medications at 6-months postoperatively (P<0.0001). At 6 months postoperatively, 95.8% had an IOP reduction of at least 20% compared to baseline and 87.5% were medication-free. There was no change in the corneal endothelial cell density (ECD).[26]

Another prospective study conducted by Feijoo and colleagues evaluated the efficacy of MINIject as a stand-alone procedure in 29 patients. Success, defined as IOP between 5-21 mmHg with ≥20% IOP reduction with or without IOP-lowering medications, was achieved in 75.9% at 6 months postoperatively. There was a statistically significant reduction in the mean IOP from a baseline of 24.6±3.8 mmHg to 14.7±6.0 mmHg at 6 months postoperatively.[27]

Denis and colleagues reported the outcomes of 21 patients who were included in their original study[26] and completed 2 years.[28] They demonstrated a significant reduction in the mean IOP from 23.2±2.9 mmHg on a mean of 2.0±1.1 glaucoma medications preoperatively to a mean of 13.8±3.5 mmHg on a mean of 1.0±1.3 glaucoma medications at 2-year postoperatively. The success rate, defined as diurnal IOP between 5-21 mmHg and IOP reduction of at least 20% compared to baseline regardless (qualified) or without the use (complete) of glaucoma medications, was 100% (qualified) and 47% (complete) at 2-years. The authors reported a mild reduction in the mean ECD from 2411 cells/mm2 preoperatively to 2341 cells/mm2 at 2-years postoperatively representing 5% decrease for matched patients.[28]

Conclusion

Augmenting the uveoscleral outflow pathway with implantation of suprachoroidal devices represents an alternative approach for treating glaucoma without creating a filtering bleb. Initial results with the Cypass Micro-Stent were promising. However, longer-term negative effects on corneal endothelial cell density led to voluntary recall of the device which will be a primary safety focus of devices moving forward in this space.

References

- ↑ Bill A, Hellsing K. Production and Drainage of Aqueous Humor in the Cynomolgus Monkey (Macaca irus). Invest Ophthalmol, 1965. Vol. 4, pp. 920-6.

- ↑ Bill A. The Aqueous Humor Drainage Mechanism in the Cynomolgus Monkey (Macaca irus) with Evidence for Unconventional Routes. Invest Ophthalmol, 1965. Vol. 4, pp. 911-9.

- ↑ Emi K, Pederson JE, Toris CB. Hydrostatic pressure of the suprachoroidal space. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1989. Vol. 30, pp. 233-8.

- ↑ Alm A, Nilsson SF. Uveoscleral outflow – A review. Exp Eye Res, 2009. Vol. 4, pp. 760-8.

- ↑ Weinreb RN, Toris CB, Gabelt BT, Lindsey JD, Kaufman PL. Effects of Prostaglandins on the Aqueous Humor Outflow Pathways. Survey of Ophthalmology, 2002. Vol. 47, pp. S53–S64.

- ↑ Heine L. Cyclodialyse, eine neue glaukomoperation. Dtsch Med Wochenschr, 1905. Vol. 31, pp. 824–6.

- ↑ Klemm M, Balazs A, Draeger J, Wiezorrek R. Experimental use of space-retaining substances with extended duration: functional and morphological results. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 1995. Vol. 233(9), pp. 592-7.

- ↑ Portney GL. Silicone elastomer implantation cyclodialysis. A negative report. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973. Vol. 89(1), pp. 10-2.

- ↑ Miller RD, Nisbet RM. Cyclodialysis with air injection in black patients. Ophthalmic Surg, 1981. Vol. 12(2), pp. 92-4.

- ↑ Alpar JJ. Sodium hyaluronate (Healon) in cyclodialysis. CLAO J, 1985. Vol. 11(3), pp. 201-4.

- ↑ Pinnas G, Boniuk M. Cyclodialysis with teflon tube implants. Am J Ophthalmol, 1969. Vol. 68(5), pp. 879-83.

- ↑ Sen SC, Ghosh A. Gold as an intraocular foreign body. Br J Ophthalmol, 1983. Vol. 67(6), pp. 398-9.

- ↑ Hueber A, Roters S, Jordan JF, Konen W. Retrospective analysis of the success and safety of Gold Micro Shunt Implantation in glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol, 2013. Vol. 13, p. 35.

- ↑ Skaat A, Sagiv O, Kinori M, Simon GJ, Goldenfeld M, Melamed S. Gold Micro-Shunt Implants Versus Ahmed Glaucoma Valve: Long-term Outcomes of a Prospective Randomized Clinical Trial. J Glaucoma, 2016. Vol. 25(2), pp. 155-61.

- ↑ Hueber A, Roters S, Jordan JF, Konen W. Retrospective analysis of the success and safety of Gold Micro Shunt Implantation in glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol, 2013. Vol. 13, p. 35.

- ↑ Figus M, Lazzeri S, Fogagnolo P, Iester M, Martinelli P, Nardi M. Supraciliary shunt in refractory glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol, 2011. Vol. 95(11), pp. 1537-41.

- ↑ Pourjavan S, Collignon N, De Groot V. STARflo™ Glaucoma Implant: 12 month clinical results. Acta Ophthalmologica: Special Issue: Abstracts from the 2013 European Association for Vision and Eye Research Conference, 2013. Vol. 91(S252).

- ↑ Pourjavan S, Collignon N, De Groot V. STARflo glaucoma implant: 12 month clinical results. Acta Ophthalmol, 2013. Vol. 91(Suppl), p. 252.

- ↑ Fili S, Janoud L, Vastardis I, Wölfelschneider P, Kohlhaas M. The STARflo™ glaucoma implant: a single-centre experience at 24 months. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 2019. Vol. 257(12), pp. 2699-2706.

- ↑ Gigon A, Shaarawy T. The Suprachoroidal Route in Glaucoma Surgery. Journal of Current Glaucoma Practice, 2016. Vol. 10(1), pp. 13-20.

- ↑ Coroneo MT. Suprachoroidal Drainage – Centenarian Progress: An Inventor’s Perspective. In Francis BA, Sarkisian S Tan J, Editors, Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery: the Science and the Practice. Thieme, New York, 2016

- ↑ Saheb H, Ianchulev T, Ahmed I. Optical coherence tomography of the suprachoroid after CyPass Micro-Stent implantation for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol, 2014. Vol. 98(1), pp. 19-23.

- ↑ García-Feijoo J, Rau M, Grisanti S, Grisanti S, Höh H, Erb C, Guguchkova P, Ahmed I, Grabner G, Reitsamer H, Shaarawy T, Ianchulev T. Supraciliary Micro-stent Implantation for Open-Angle Glaucoma Failing Topical Therapy: 1-Year Results of a Multicenter Study. Am J Ophthalmol, 2015. Vol. 159(6), pp. 1075-1081.

- ↑ Hoeh H, Vold SD, Ahmed IK, Anton A, Rau M, Singh K, Chang DF, Shingleton BJ, Ianchulev T. Initial Clinical Experience With the CyPass Micro-Stent: Safety and Surgical Outcomes of a Novel Supraciliary Microstent. J Glaucoma, 2016. Vol. 25(1), pp. 106-12.

- ↑ Höh H, Grisanti S, Grisanti S, Rau M, Ianchulev S. Two-year clinical experience with the CyPass micro-stent: safety and surgical outcomes of a novel supraciliary micro-stent. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd, 2014. Vol. 231(4), pp. 377-81.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 26.2 Denis P, Hirneiß C, Reddy KP, Kamarthy A, Calvo E, Hussain Z, et al. A First-in-Human Study of the Efficacy and Safety of MINIject in Patients with Medically Uncontrolled Open-Angle Glaucoma (STAR-I). Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2019;2(5):290-7.

- ↑ García Feijoó J, Denis P, Hirneiß C, Aptel F, Perucho González L, Hussain Z, et al. A European Study of the Performance and Safety of MINIject in Patients With Medically Uncontrolled Open-angle Glaucoma (STAR-II). J Glaucoma. 2020;29(10):864-71.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Denis P, Hirneiß C, Durr GM, Reddy KP, Kamarthy A, Calvo E, et al. Two-year outcomes of the MINIject drainage system for uncontrolled glaucoma from the STAR-I first-in-human trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106(1):65-70.