Spheroidal Degeneration

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Unspecified conjunctival degenerations ICD-10: H11.10

Disease

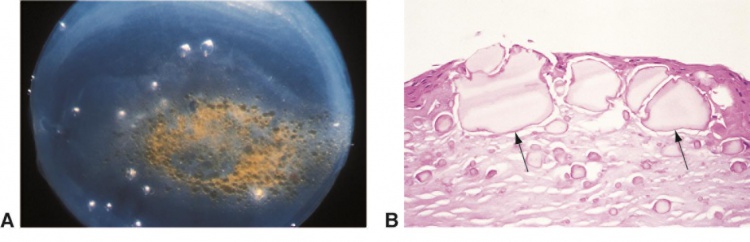

Spheroidal keratopathy is a degeneration of the cornea and/or conjunctiva, characterized by homogeneous, translucent, fine, golden yellow, spherules, or globules of varying size located in the superficial corneal stroma, Bowman's membrane, and subepithelium, and at the epithelium in advanced cases.[1] It is also known as climatic droplet keratopathy, actinic keratopathy, Bietti’s band-shaped nodular dystrophy, Labrador keratopathy, and many other names based on geographic locations and races that are most affected by the condition.[2][3]

Etiology

The source of the proteinaceous material forming the droplets is not well understood. Proposed theories include the diffusion of serum proteins from the limbal vessels to the cornea as a result of interactions with ultraviolet light.[3] Physical irritation to the corneal surface from the environment, such as sand, ultraviolet light, wind, and welding burns, have been associated with the development and progression of spheroidal degeneration.

Risk Factors

Increasing age and exposure to ultraviolet light are the most common associated risk factors. Other factors include dry eyes, malnutrition, corneal trauma, or microtrauma from wind, sand or ice, low humidity, and extreme temperatures.[2] [4] Associated ocular diseases include keratitis, lattice corneal dystrophy, and glaucoma.[5] Welding burns have also been recognized as an occupational risk.[1][4]

Epidemiology

A cohort study done in Labrador communities located in Eastern Canada showed that the highest prevalence of spheroidal keratopathy occurred between latitudes 55° - 56° north of the equator, where the ultraviolet light reflected from ice and snow serves as the greatest risk factor. Men are affected more than women.[4] Similarly, low latitudes, around the equator, where sand and UV light exposure are more prevalent, also serve as risk factors.

General Pathology

All classifications of spheroidal keratopathy are pathologically indistinguishable by both light and electron microscopy. Light microscopy demonstrates extracellular deposits in different sizes and shapes, such as spherical, elongated, or angular, in the subepithelium, Bowman membrane, and superficial stroma of the cornea. The epithelium and basement membrane are affected only in advanced stages, during which the Bowman's membrane is often disrupted or absent locally. Usually, inflammatory cells are absent.[1] Slit-lamp examination reveals the lesion in droplets in low magnification, which disappear under higher magnification.[6]

Under light microscopy, the lesions stain blue-green with toluidine blue, bright red with methyl green-pyronin, and variable pink with Gomori’s aldehyde fuchsin (which demonstrates the collagenous component), and stains eosinophilic with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Under electronic microscopy, finely granular structures are collected on bands of collagen.[6] The deposited material in spheroidal degeneration is made of protein.[7]

Pathophysiology

The source of the spherules-forming material remains unelucidated. However, previous studies have suggested that accumulation of plasma proteins, possibly immunoglobulins, and albumins, could diffuse into the cornea from the limbal circulation and are modified by UV radiation.[1] It has also been hypothesized that the deposits were secretory products of the epithelium and/or stroma, which contains incomplete collagen or degraded stromal collagen. However, this notion has not been explained by pathologic findings.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of spheroidal keratopathy is mostly based on clinical presentation. Biopsy and histology help to support and confirm the diagnosis, but are not necessary for diagnosis.

Physical examination

The clinical appearance is characterized by the presence of yellow or golden spherules or “droplets” at or beneath the corneal or conjunctival epithelium. The lesions are located in the superficial corneal stroma, Bowman’s membrane, subepithelium, and rarely in the epithelium in the advanced stage of the disease. Depending on the location and the etiology of the lesions, the clinical features have been categorized into three forms by Fraunfelder FT and colleagues[5][8]:

- primary corneal,

- secondary corneal, and

- conjunctival.

In the primary form, the lesions are usually presented at the horizontal limbus within the palpebral fissure and gradually progress to towards the central cornea, and the rest of the cornea is free of other pathology. In the secondary corneal form, the lesions are usually located at sites of the previous pathologies, such as trauma, neovascularization, or inflammation, and it can be presented either unilateral or bilateral depending on the etiology of the prior lesion. In the conjunctival form, the lesions are located at 3 and 9 o’clock positions interpalpebrally due to its association with pinguecula.[2]

Symptoms

The majority of patients are asymptomatic. When lesions involve the central cornea, patients may experience reduced visual acuity.[2]

Clinical diagnosis

Johnson and Ghosh have proposed the following grading system to describe the clinical features of spheroidal degeneration.[9]

- Trace: A small number of lesions that are found in one eye or only one end of interpalpebral strips in each eye bilaterally.

- Grade 1: Lesions involving the interpalpebral cornea horizontally but not involving the central cornea.

- Grade 2: Central corneal involvement without affecting visual acuity

- Grade 3: Central corneal involvement with a decline in visual acuity.

- Grade 4: Grade 3 features with lesion elevation

Differential diagnosis

Clinically, there are many other diagnoses that have similar presentations, which include corneal amyloid degeneration, gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy (familial subepithelial amyloidosis), band keratopathy, climatic proteoglycan stromal keratopathy, primary lipoidal degeneration of the cornea, Salzmann nodular degeneration, and limbal girdle of Vogt, type II.[2]

Management

Prevention: Although no known preventative measure was proven to reduce the occurrence, limiting sun exposure may reduce disease development and progression.

General treatment

The prognosis is generally good, and the majority of patients do not require treatment. Only severe cases affecting vision need to be treated. In patients with central corneal involvement and reduced visual acuity, different treatments can be considered depending on the depth and density of the deposits. Treatments may include superficial keratectomy, phototherapeutic keratectomy, lamellar keratoplasty, or penetrating keratoplasty in the most severe cases.[1] [2] [7] [10]

Complications

Although the disease is slow in progression, significant visual compromise is a long-term consequence in untreated patients, especially in areas of the world with severe environmental or climatic exposure. Elevated lesions may progress to complications such as epithelial defects, recurrent corneal erosions, or sterile ulceration. Due to possible reduced corneal sensation because of the deposits, sterile ulcerations may progress to microbial keratitis or perforate rapidly.[2]

Prognosis

The prognosis is generally good, and the majority of patients do not require treatment.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Magovern M, Wright JD, Mohammed A. Spheroidal degeneration of the cornea: A Clinicopathologic Case Report. 2004;23(1):84-88.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Meyer JJ. Climatic Droplet Keratopathy (Spheroidal Degeneration). In: Schmidt-Erfurth U, Kohnen T, eds. Encyclopedia of Ophthalmology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2016:1-4. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35951-4_772-1.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Farjo QA, Sugar A (2009) Corneal degenerations. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS (eds) Ophthalmology, 3rd edn. Mosby/Elsevier, St. Louis, pp 318–323

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Johnson GJ, Ghosh M (1975) Labrador keratopathy: clinical and pathological findings. Can J Ophthalmol 10:119–135

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Fraunfelder FT, Hanna C (1973) Spheroidal degeneration of cornea and conjunctiva; 3. Incidences, classification, and etiology. Am J Ophthalmol 76:41–50

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Hanna C. A Common Ocular Pathology Spheroidal Degeneration Of the Cornea and Conjunctiva. In: Cool SJ, Smith EL, eds. Frontiers in Visual Science: Proceedings of the University of Houston College of Optometry Dedication Symposium, Houston, Texas, USA, March, 1977. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 1978:22-27. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-35397-3_4.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 Gray RH, Johnson GJ, Freedman A (1992) Climatic drop- let keratopathy. Surv Ophthalmol 36:241–253

- ↑ Fraunfelder FT, Hanna C, Parker JM. Spheroid degeneration of the cornea and conjunctiva 1. Clinical course and characteristics. Am J Ophthalmol 1972;74:821-8.

- ↑ Johnson GJ, Ghosh M (1975) Labrador keratopathy: clin- ical and pathological findings. Can J Ophthalmol 10:119–135

- ↑ Dasar L, Pujar C, Singh Gill K, Patil M, Salagar M. Indications of Penetrating Keratoplasty in Southern India. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2013;7(11):2505-2507. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/7030.3591.