Social Determinants of Health: Ophthalmic Implications

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are conditions that affect people’s health risks and outcomes [1] [2]. These elements are an interaction between structural, patient-level, provider, and healthcare system factors[1]. These include living conditions, socioeconomic status, education levels, and even personal identities[2]. The past few decades have provided increasing evidence that SDOH play an important role in propagating health disparities and shaping health outcomes. Systematic differences between population groups not only affect health status but can also determine life expectancy [2]. Therefore, it is not surprising that these key drivers also have ophthalmic implications. Research shows that SDOH are tightly linked with vision loss[1] [2] [3]. For example, a study by Su et al. demonstrated that lower education level, Medicaid insurance, food insecurity, difficulty paying medical bills, and identifying as a gay male, were significantly associated with self-reported visual difficulty [4].

Categories of Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health can be broken down into five main domains:

- Education access and quality: Increasing education levels are directly correlated with higher income, safer living conditions, and improved health literacy [6]. As such, these individuals are likely to live longer and have better health outcomes.

- Health care access and quality: Disadvantaged population groups make up a substantial portion of the uninsured, creating a large barrier to accessing quality health care [8]. Other obstacles include lack of transportation, language as well as cultural differences, provider bias, and low health literacy [1].

- Ophthalmic implications: Lack of healthcare puts patients at a higher risk of avoiding doctor’s visits or not seeking out an eye exam [7].

- Neighborhood and built environment: Neighborhood crime rates, housing quality, transportation access, air, and water pollution as well as the availability of healthy foods, are important considerations for wellness [1][2][9].

- Ophthalmic implications: Safety concerns in neighborhoods are associated with higher BMI and obesity [10]. This increases the prevalence of metabolic disorders and subsequent complications. Underserved communities are also less likely to follow through with initial diabetic retinopathy screening referrals [11]. Additionally, a study conducted by the American Academy of Ophthalmology found that food insecurity was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving eye care.[12] Furthermore, those experiencing food insecurity have higher odds of self-reported visual impairment (SRVI), and diabetic retinopathy diagnosis, and are less likely to receive timely eye care. [13]

- Economic stability: Socioeconomic status is all-encompassing and influences other domains as well. To name a few, this category includes employment status, food security, and housing stability [1].

- Social and community context: This category encompasses family, civic participation, and community networks [2]. These avenues create the necessary support system to promote positive health effects.

Common Eye Diseases and Visual Outcome Disparities

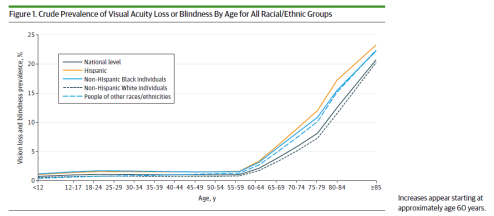

According to the CDC, visual impairment is one of the most common disabilities in the United States [1][15]. By 2050, blindness is expected to double to 2 million due to the aging population and continual increase in chronic diseases like diabetes [16]. Ethnic minorities are expected to experience an increased prevalence of visual impairment and blindness. This is due to the fact that minorities are disproportionately affected by poverty, lower levels of education, live in more dangerous neighborhoods and have poor access to quality healthcare [2]. Concurrently, these communities have an increased probability of being diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy, primary open-angle glaucoma and visual impairments due to cataracts [2] [14] [17] [18]. Despite these risk factors, they are also less likely seen by an ophthalmologist [2] [7].

- Diabetic Retinopathy (DR): Unlike other retinal pathologies, diabetic retinopathy is largely preventable with screenings and early detection [19]. Currently in the United States, DR has a prevalence rate of 30% in people over 40 [14]. Racial minorities are disproportionately affected and have worse visual outcomes. For example, the Salisbury Eye Evaluation found a 4-fold increase in visual impairments in blacks compared to whites [20]. The Los Angeles Latino Study (LALES) has also demonstrated a high incidence of DR and related visual impairments in the Latinx community [21]. Due to the multidimensional barriers discussed above, African American and Hispanic patients are more likely to present in severe stages and subsequently have worse prognoses.

- Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG): POAG is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness and also affects racial minorities at an unbalanced rate [22][23]. Despite the high prevalence, there is a considerable gap in disease surveillance and appropriate treatment in these communities. A study by Elam et al. demonstrated that Medicaid recipients with new POAG are less likely to receive glaucoma testing in the 15 months after initial diagnosis when compared to commercial insurances [17]. These disparities were especially magnified in black patients, who had 291% higher odds of not undergoing appropriate testing when compared to their black counterparts with non-Medicaid insurance.

- Cataracts: About 20 million Americans are diagnosed with cataracts in one or both eyes [1]. Cataracts, while easily treatable, still remain the leading cause of blindness in the world [24]. Despite increased access in the industrialized world, ethnic minorities, individuals living in rural areas, and patients with lower socioeconomic status appear to have higher rates of visual impairments and blindness from cataracts [18]. These communities live in more impoverished areas, are less likely to visit an ophthalmologist, and have a higher incidence of diabetes, which is a known risk factor.

- Uncorrected Refractive Errors (URE): URE is currently the second leading cause of blindness in the world [25]. This has significant economic implications, with substantial social costs and reduced productivity associated with visual impairments [26]. It also affects participation in activities of daily living and facilitates poor social integration. Social determinants of health are responsible for the high prevalence rates of URE in certain communities. For example, economic barriers, limited healthcare access, poor health literacy, and non-white ethnicity are key drivers in these visual outcome disparities [26].

Food Insecurity and Ophthalmic Outcomes

Introduction

The United States Department of Agriculture conducts an annual survey to examine the prevalence of food security in U.S. households. The 2022 report found that 87.22% of American households were food secure, which is defined as each member of a home always having access to enough food for an active and healthy life.[27] It is notable that this percentage is a significant drop from the previous year’s 89.8% of households being food secure.[27] It is also notable that in 2019 the USDA reported that 33.2% of low-income individuals live in food deserts, where households are located more than a mile away from the nearest grocery store. This correlates to an estimated 11-27% of the U.S. population.[28] With the rise of food insecurity and the evidence of its association with negative health outcomes, it is important to consider how food insecurity may be implicated in ophthalmic health.[29]

Food insecurity can be broken down into two categories.

- Low food security: Households that use strategies to avoid disrupting their eating patterns and avoid reducing food intake. Examples of these strategies include a less varied diet, food assistance programs, and food pantries.

- Very low food security: Households that have one or more members whose eating patterns and food intake are disrupted and reduced due to lack of resources.[27]

Not only is food insecurity associated with poorer health outcomes, but it is also associated with higher uninsured rates, delayed and lower access to care, and increased emergency room visits.[30]

Food access and nutrition play such a vital role in vision care that the American Academy of Ophthalmology Taskforce on Disparities in Eye Care specifically includes food access as part of the social determinants of vision health. A retrospective cross-sectional study assessed the primary outcome of visits to an eye care practitioner in the past 12 months self-reported by patients with type two diabetes. With a focus on investigating patients’ perspectives on what factors led to discrepancies in screening rates, recommended by the Academy of Ophthalmology to be done yearly, 1,551 adults were surveyed. Food insecurity, amongst other factors, was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving eye care.[12]

Importance of Nutrition in Eye Health

Among the various causes of vision impairment, the top four conditions with the highest prevalence in developed nations, in descending order, include diabetic retinopathy, cataract, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and glaucoma.[31] Despite their differences, there are similarities in how these conditions are believed to induce tissue damage– primarily through chronic oxidative damage or inflammation affecting the lens, retina, or optic nerve.[31] Therefore, interventions targeting the reduction of oxidative stress may have benefits in impeding disease progression in these conditions, as well as those focused on minimizing or preventing pro-inflammatory states. One such intervention involves dietary modifications.

Carotenoids are fat-soluble pigments found in dark green leafy vegetables and in flavonoids derived from fruits and vegetables that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics.[32] Since oxidative and inflammatory stress play a role in the pathogenesis in AMD, The National Eye Institute recommends eating dark-green vegetables to decrease onset and advancement of the AMD.[33] The impact of consuming green leafy vegetables may be heightened when coupled with other lifestyle adjustments, such as quitting smoking, possibly through a cumulative effect. However, educating patients about lifestyle changes becomes more challenging in food deserts, where access to these beneficial foods may be limited.

Some studies have found that long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, mostly from fish, can lower the development and progression of AMD. The BMES study found that individuals who had a higher intake of omega-3 fatty acids alongside low omega-6 fatty acids exhibited a 50% decreased risk of developing early AMD. However, with high levels of omega-6 fatty acids, a high intake of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids did not provide protective benefits.[34] Further research is needed on the role of the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The main contributor to cataract formation apart from age is oxidative stress caused by normal metabolic processes. Dietary changes that could help include increased consumption of carotenoids, antioxidants, and vitamins A, B, C, and E. Vitamin C from fruit and vegetables and vitamin E have been shown to reduce reactive oxygen species and prevent oxidative stress.[35]

The Mediterranean diet has been researched in association with eye health. The diet is plant-based and low in saturated fats. Foods recommended include fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and nuts, which contain higher vitamin and antioxidant properties. Following this diet has been shown to lower the occurrence of type 2 diabetes and avert the onset of diabetic retinopathy in patients with diabetes.[32] It has also shown to be effective in preventing vision loss associated with cataracts, AMD, and retinal vein occlusion. [32]This can be attributed to the role plant-based and Mediterranean diet have in lowering the risk factors of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

Food Insecurity and Visual Impairment

Research has shown that food insecurity and visual impairment have a cyclical relationship. Studies have found that those experiencing food insecurity have higher odds of self-reported visual impairment (SRVI), and diabetic retinopathy diagnosis, and are less likely to receive timely eye care. These results are pronounced in older adults, with one cross-sectional study finding that very low food security status in people 50 and older was associated with 170% higher odds of objective visual impairment and 85% higher odds of SRV compared with those with full food security, increased odds were more pronounced with increased age.[13]

Visual impairment can also contribute to food insecurity, as increased levels of visual impairment are associated with unemployment.[36] Only 44% of people with visual impairment are employed, and it is estimated that 50% of people with visual impairment have removed themselves from the labor force and unemployment is one of the leading causes of food insecurity in America.[36][37]Therefore those who are visually impaired have greater levels of unemployment, which greatly contributes to food insecurity. Additionally, in a study by Jih and colleagues, an analysis of the 2013 Health and Retirement Study (HRS) found that experiencing visual impairment independently and in addition to other chronic conditions put older adults at a greater risk of experiencing food insecurity.[38] These findings indicate that food insecurity and visual impairment have a bidirectional relationship.

Diabetic Retinopathy and Food Insecurity

A growing body of research has examined the relationship between food insecurity and diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic retinopathy is one of the leading causes of preventable blindness, disproportionately impacting minority populations. [39]Several studies have linked food insecurity to reduced preventive eye care and poorer diabetes management among those with diabetic retinopathy. A study on diet highlights that oxidative stress and inflammation are key factors in conditions like diabetic retinopathy and consuming a diet rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory foods can slow down disease progression and sometimes even prevent it entirely. [31]

In a recent cross-sectional study, found that food insecurity was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving recommended annual eye exams in patients with diabetes. Additionally, food insecurity has been connected to suboptimal glycemic control, which can hasten the progression of diabetic retinal complications.[40]

An analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed a higher prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among food insecure diabetic patients compared to their food-secure counterparts.[40] Racial minorities, those with less education and income, and individuals reporting depression were also more likely to have diabetic retinopathy.

Similarly, a study identified food insecurity as one of several social determinants of health, along with housing insecurity and mental health concerns, that were linked to reduced eye care utilization.[41]

Taken together, these findings indicate food insecurity is highly prevalent among those with diabetes and associated with lower adherence to eye care recommendations and poorer glycemic control. Increased screening for food insecurity and interventions to address it through enhanced diabetes education and management support could potentially improve outcomes related to diabetic retinopathy. Further randomized controlled trials are warranted to establish causal relationships.

Maternal Nutrition and Fetal Eye Health

Adequate maternal nutrition is critical to the ocular health of the developing fetus. Adherence to Western dietary patterns is reportedly associated with a higher incidence of primary congenital glaucoma and anterior segment defects.[42] Pregnant individuals who consumed higher levels of docosahexaenoic acid were found to have children with better visual acuities at four months of age and three and a half years of age.[43] Insufficient maternal intake of fatty acids during development may increase the risk of altered visual acuity in the baby.[44] Additionally, maternal consumption of a high-quality diet, as assessed by the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS-P) and Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI-P), was associated with better visual-spatial skills in offspring in early childhood.[45]

There is a documented relationship between retinoblastoma and parental nutrition. A study conducted by Lombardi et al. found a negative association between retinoblastoma and maternal fruit consumption.[46] Mothers who consumed more fried foods and cured meats while pregnant were more likely to have retinoblastoma in their children.[46] Another study by Jung et al. reported that higher maternal intake of vitamin A and vitamin D was protective against unilateral spontaneous retinoblastoma in offspring.[47] Additionally, paternal consumption of nutrients found in dairy products such as calcium in the year before a child’s conception and maternal use of multivitamin supplements have a protective effect against retinoblastoma.[48]

Importance of Nutrition in Neuro-ophthalmic Conditions

Optic neuropathy can occur from deficiencies in nutrition, such as a lack of essential vitamins. Vitamin B has been studied to have a direct link to metabolic neuropathies, which cause vision loss. Specifically, vitamin B9, B12, B1, B6, otherwise known as neurotropic vitamins, are required by the body to support optic health, such as in processes such as mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. A primary factor that often leads to the deficiencies of these vitamins include malnutrition.[49] Clinicians should thus prioritize patients residing in food insecure environments who struggle to receive vitamins. Patients who face shortages in vitamin intake are at risk to further develop deficiencies in ocular health, so ensuring adequate access to food can prevent further ocular pathologies.

How to Address Social Determinants of Health

Eye care providers can hold an important role in mitigating ocular health disparities. Understanding the interplay between social factors and general as well as ocular health is the first step. Acknowledging and addressing preexisting biases is also key to providing equitable healthcare in the context of varying socioeconomic status, education levels, or ethnic backgrounds [2].

Furthermore, interventions involving policymakers, clinicians, and healthcare providers are needed to implement macro-level policies to help screen and expand on policies to address unmet needs. Ophthalmologists should consider enhancing routine patient encounters by accessing social needs in a comprehensive or targeted manner[50]. There are several screening tools available through the American Academy of Family Physicians [51], American Academy of Pediatrics [52] and Kaiser Permanente [53] for providers to utilize. Another essential strategy includes collaborating with social workers and legal services [50] to identify and advertise available resources in the community (i.e., transportation vouchers, prescription coupons, insurance registration, etc.). Inequities related to food access or food insecurity should be addressed through further advocacy in improving financial and nutrition assistance programs. Expanding eligibility on current social programs such as SNAP and Commodity Supplement Food Program for older adults with eye diseases will alleviate anxiety and stress in obtaining food.[54][55] Providing accessible healthy food options and nutrition through programs such as the USDA Farmers to Families Food Box, can also be an option to allocate healthy food options to areas in need.[56] Of course, providing healthy food retailing is key, thus policies should advocate for economic incentives, better zoning regulations, and accessible transportation routes to improve such healthy food outlets in communities. Building such systems will not only improve eye-related health outcomes but effectively address a holistic standard of care in medicine.

To provide holistic ophthalmic care, it is also important to consider a patient’s culture, communication style, family dynamics, trust or mistrust in healthcare, gender identity, and sexual orientation [2]. Additionally, reducing language barriers and focusing on patient education in day-to-day practice can address potential obstacles to treatment. Eye care providers can also expand access by providing services in community health centers and vision outreaches in underserved areas.

The promotion of diversity, equity, and inclusion in ophthalmology is another integral part of this process. Combating eye care inequities will involve utilizing population data analytics, including racial minorities in research and participating in advocacy [57]. Perhaps it is also time to develop screening toolkits specific to ophthalmology to better understand patients’ risk factors and identify ways to improve vision outcomes in disadvantaged communities. Finally, it is imperative to build systems in place that will ensure the ophthalmology workforce will mirror the population it serves.

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Social Determinants of Health, Health Equity, and Vision Loss | subsection title | section title | site title. Published June 15, 2021. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/determinants/index.html

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Diversity - American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed August 17, 2022. Chapter 17; Section 1, Update on General Medicine.

- ↑ Ulldemolins AR, Lansingh VC, Valencia LG, Carter MJ, Eckert KA. Social inequalities in blindness and visual impairment: A review of social determinants. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012;60(5):368-375. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.100529

- ↑ Su NH, Moxon NR, Wang A, French DD. Associations of Social Determinants of Health and Self-Reported Visual Difficulty: Analysis of the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020;27(2):93-97. doi:10.1080/09286586.2019.1680703

- ↑ CDC - Social Determinants of Health - STLT Gateway. Published August 9, 2022. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/sdoh/index.html

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6 Suppl):S53-62.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Barsegian A, Kotlyar B, Lee J, Salifu MO, McFarlane SI. Diabetic Retinopathy: Focus on Minority Populations. Int J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;3(1):034-045. doi:10.17352/ijcem.000027

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 The Uninsured| A Primer. Published Nov, 2015. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://files.kff.org/attachment/primer-the-uninsured-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-in-the-era-of-health-reform

- ↑ Neighborhood and Built Environment - Healthy People 2030 | health.gov. Accessed August 16, 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/neighborhood-and-built-environment

- ↑ Fish JS, Ettner S, Ang A, Brown AF. Association of Perceived Neighborhood Safety on Body Mass Index. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2296-2303. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.183293

- ↑ Yusuf R, Chen EM, Nwanyanwu K, Richards B. Neighborhood Deprivation and Adherence to Initial Diabetic Retinopathy Screening. Ophthalmology Retina. 2020;4(5):550-552. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2020.01.016

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Ravindranath R, Bernstein IA, Fernandez KS, Ludwig CA, Wang SY. Social Determinants of Health and Perceived Barriers to Care in Diabetic Retinopathy Screening. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(12):1161–1171. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2023.5287

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Kolli A, Mozaffarian RS, Kenney EL. Food Insecurity and Vision Impairment Among Adults Age 50 and Older in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;236:69-78. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.10.002

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 14.2 Coney JM, Scott AW. Racial disparities in the screening and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2022;114(2):171-181. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2021.12.011

- ↑ Fast Facts of Common Eye Disorders | CDC. Published June 9, 2020. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basics/ced/fastfacts.htm

- ↑ Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B, et al. Visual Impairment and Blindness in Adults in the United States: Demographic and Geographic Variations From 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(7):802-809. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284

- ↑ Jump up to: 17.0 17.1 Elam AR, Andrews C, Musch DC, Lee PP, Stein JD. Large Disparities in Receipt of Glaucoma Care between Enrollees in Medicaid and Those with Commercial Health Insurance. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(10):1442-1448. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.003

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Desai N, Copeland RA. Socioeconomic disparities in cataract surgery. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2013;24(1):74-78. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32835a93da

- ↑ Fairless E, Nwanyanwu K. Barriers to and Facilitators of Diabetic Retinopathy Screening Utilization in a High-risk Population. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(6):1244-1249. doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00627-3

- ↑ Muñoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, et al. Causes of Blindness and Visual Impairment in a Population of Older Americans: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2000;118(6):819-825. doi:10.1001/archopht.118.6.819

- ↑ Varma R, Paz SH, Azen SP, et al. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study: design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(6):1121-1131. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.001

- ↑ Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, Royall RM, Quigley HA, Javitt J. Racial Variations in the Prevalence of Primary Open-angle Glaucoma: The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991;266(3):369-374. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03470030069026

- ↑ Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1439-1448. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025

- ↑ Steinmetz JD, Bourne RRA, Briant PS, et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the Right to Sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet Global Health. 2021;9(2):e144-e160. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7

- ↑ Naidoo KS, Leasher J, Bourne RR, et al. Global Vision Impairment and Blindness Due to Uncorrected Refractive Error, 1990–2010. Optometry and Vision Science. 2016;93(3):227-234. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000796

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 Jeganathan VSE, Robin AL, Woodward MA. Refractive Error in Underserved Adults: Causes and Potential Solutions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28(4):299-304. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000376

- ↑ Jump up to: 27.0 27.1 27.2 Rabbitt, M.P., Hales, L.J., Burke, M.P., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2023). Household food security in the United States in 2022 (Report No. ERR-325). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://doi.org/10.32747/2023.8134351.ers

- ↑ Rhone A, Michele Ver Ploeg, Williams R, Breneman V. Understanding Low-Income and Low-Access Census Tracts Across the Nation: Subnational and Subpopulation Estimates of Access to Healthy Food. Economic Information Bulletin. Published online January 1, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.289136

- ↑ Leung CW, Kullgren JT, Malani PN, et al. Food insecurity is associated with multiple chronic conditions and physical health status among older US adults. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101211. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101211

- ↑ Park S, Chen J, Bustamante AV. Adverse Consequences of Food Insecurity Among U.S. Adults Beyond Health Outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(1):146-153. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2023.09.003

- ↑ Jump up to: 31.0 31.1 31.2 Broadhead GK, Hong T, Bahrami B, Flood V, Liew G, Chang AA. Diet and risk of visual impairment: a review of dietary factors and risk of common causes of visual impairment. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(6):636-650. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaa100

- ↑ Jump up to: 32.0 32.1 32.2 Mulpuri L, Sridhar J, Goyal H, Tonk R. The relationship between dietary patterns and ophthalmic disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2023;34(3):189-194. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000943

- ↑ Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). NIH National Eye Institute. Published June 22, 2021. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/age-related-macular-degeneration

- ↑ Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, Mitchell P. Dietary fatty acids and the 10-year incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):656-665. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.76

- ↑ Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE. Incidence of age-related cataract: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(2):219-225. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.2.219

- ↑ Jump up to: 36.0 36.1 McDonnall MC, Sui Z. Employment and Unemployment Rates of People Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired: Estimates from Multiple Sources. J Vis Impair Blind. 2019;113(6):481-492. doi:10.1177/0145482X19887620

- ↑ Hunger and Food Insecurity. Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity

- ↑ Jih J, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Seligman HK, Boscardin WJ, Nguyen TT, Ritchie CS. Chronic disease burden predicts food insecurity among older adults. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(9):1737-1742. doi:10.1017/S1368980017004062

- ↑ Nwanyanwu KH, Andoh J, Chen E, Xu Y, Deng Y. Social Determinants of Health in Diabetic Retinopathy in the US: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2005-2008). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(8):1135-1135.

- ↑ Jump up to: 40.0 40.1 Gibson DM. Food Insecurity, Eye Care Receipt, and Diabetic Retinopathy Among US Adults with Diabetes: Implications for Primary Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1700-1702. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04992-x

- ↑ Ravindranath R, Bernstein IA, Fernandez KS, Ludwig CA, Wang SY. Social Determinants of Health and Perceived Barriers to Care in Diabetic Retinopathy Screening. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141(12):1161-1171. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2023.5287

- ↑ Moore KJ, Carmichael SL, Forestieri NE, et al. Maternal diet as a risk factor for primary congenital glaucoma and defects of the anterior segment of the eye in the National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Birth Defects Res. 2020;112(6):503-514. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1664

- ↑ Judge MP, Harel O, Lammi-Keefe CJ. A docosahexaenoic acid-functional food during pregnancy benefits infant visual acuity at four but not six months of age. Lipids. 2007;42(2):117-122. doi:10.1007/s11745-006-3007-3

- ↑ Cortés-Albornoz MC, García-Guáqueta DP, Velez-van-Meerbeke A, Talero-Gutiérrez C. Maternal Nutrition and Neurodevelopment: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2021;13(10):3530. Published 2021 Oct 8. doi:10.3390/nu13103530

- ↑ Mahmassani HA, Switkowski KM, Scott TM, et al. Maternal diet quality during pregnancy and child cognition and behavior in a US cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022;115(1):128-141. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab325

- ↑ Jump up to: 46.0 46.1 Lombardi C, Ganguly A, Bunin GR, et al. Maternal diet during pregnancy and unilateral retinoblastoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(3):387-397. doi:10.1007/s10552-014-0514-z

- ↑ Jung EM, Bunin GR, Ganguly A, Johnson RA, Spector LG. The association between maternal nutrient intake during pregnancy and the risk of sporadic unilateral retinoblastoma among offspring. Cancer Epidemiol. 2023;85:102376. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2023.102376

- ↑ Bunin GR, Li Y, Ganguly A, Meadows AT, Tseng M. Parental nutrient intake and risk of retinoblastoma resulting from new germline RB1 mutation. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(2):343-355. doi:10.1007/s10552-012-0120-x

- ↑ Roda M, di Geronimo N, Pellegrini M, Schiavi C. Nutritional Optic Neuropathies: State of the Art and Emerging Evidences. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2653. Published 2020 Aug 31. doi:10.3390/nu12092653

- ↑ Jump up to: 50.0 50.1 Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19-31.

- ↑ Social Needs Screening Tool - American Academy of Physicians. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/everyone_project/hops19-physician-form-sdoh.pdf

- ↑ Screening Tool Finder. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/screening-technical-assistance-and-resource-center/screening-tool-finder/?page=1

- ↑ Find Tools:: Risk Screening Tools Review. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://sdh-tools-review.kpwashingtonresearch.org/find-tools

- ↑ Oronce CIA, Miake-Lye IM, Begashaw MM, Booth M, Shrank WH, Shekelle PG. Interventions to Address Food Insecurity Among Adults in Canada and the US: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(8):e212001. Published 2021 Aug 6. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.2001

- ↑ Food Security and Nutrition Assistance. Economic Research Service U.S. Department of Agriculture. Published November 29, 2023. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-security-and-nutrition-assistance/

- ↑ USDA Farmers to Families Food Box. USDA Agricultural Marketing Service U.S. Department of Agriculture. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.ams.usda.gov/selling-food-to-usda/farmers-to-families-food-box

- ↑ Diversity - American Academy of Ophthalmology. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.aao.org/diversity-equity-and-inclusion