Scleromalacia Perforans

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Scleromalacia Perforans (SP). ICD-10: H15.053

Disease

Anterior necrotizing scleritis without inflammation, so called scleromalacia perforans, is a rare, severe eye disorder developing an autoimmune damage of episcleral and scleral performing vessels (hypersensitivity type III).[2]

History Of Disease

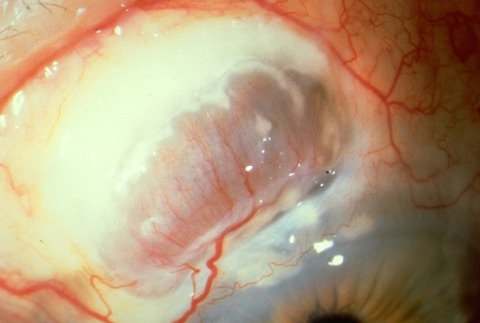

Scleromalacia perforans was first reported by van der Hoeve in a talk given before the Royal Dutch Ophthalmological Society in 1930. He noted that it was bilateral, began with yellow or greyish subconjunctival nodules and gradually developed into scleral necrosis with perforation and exposure of the uvea. Scleromalcia perforans (SP) is a rare (only 4% of scleritis).

Etiology

It is a type III hypersensitivity reaction which occurs due to accumulation of immune complexes (Antigen-Antibody complexes).

Risk Factors

Scleromalacia perforans typically occurs in elderly women with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. Other associated conditions are systemic lupus erythematosus, periarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener granulomatosis), Behçet disease, limited scleroderma, Crohn’s disease, graft-versus-host disease. SP was also observed in porphyria and herpes-zoster infection.[2]

General Pathology

Chronic granulomatous changes with epithelioid cells surround central, necrotic masses (collagen and non-collagen fibers, cell debris) .

Pathophysiology

Young and Watson suggest three determinants of scleral destruction: activation of scleral fibrocytes and resorption of pericellular matrix, infiltration of the scleral stroma by inflammatory cells, prolonged local vaso-occlusion. In SP dense plaques of necrotic tissues are removed and it is associated with full thickness loss of conjunctiva and insufficiency of conjunctival epithelium to resurface the exposed area.[2]

Diagnosis

Symptoms

The onset is gradual. Most patients complains of non-specific irritation. Pain is generally absent and vision is unaffected. The change in scleral color is often detected by patient’s family, by patient looking in the mirror or by an ophthalmologist during routine examination.

Signs

Necrotic scleral plaques near the limbus without vascular congestion. Coalescence and enlargement of necrotic areas. The sclera thins and the underlying dark uveal tissue becomes visible. In many cases, the uvea is covered with only thin connective tissue and conjunctiva. A bulging staphyloma develops if intraocular pressure is elevated; spontaneous perforation is rare, although these eyes may rupture with minimal trauma.

Clinical diagnosis

Scleromalacia perforans is a clinical diagnosis. However, laboratory testing is often necessary to evaluate any associated underlying connective tissue and autoimmune disease.

Laboratory test

Autoimmune connective tissue disorders like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, sero-negative spondylarthropathies , granulomatosis with polyangiitis and polyarteritis nodosa should be ruled out. boratory tests include complete blood count (CBC) with differential, erythrocye sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP), serum autoantibody screen (including antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies), urinalysis, syphilis serology, serum uric acid and sarcoidosis screen.

Differential diagnosis

Scleral Hyaline Plaque: age-related hyaline degeneration of the sclera. Plaque lies in the palpebral fissure immediately anterior to the medial rectus muscle insertion. Senile Scleromalacia: is a scleral disease which occurs by expulsion of a calcified plaque in advanced cases of senile scleral plaques.[3]

Management

General treatment

There is no specific therapy . Protection from trauma is important. The underlying systemic disease should be treated aggressively.[4]

Medical therapy

NSAIDS

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the initial agent of choice. These consist of non-selective or selective cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (COX inhibitors). Non-selective COX-inhibitors such as flurbiprofen, indomethacin and ibuprofen may be used. Indomethacin 50mg three times a day or 600mg of ibuprofen three times a day may be used. Patients using oral NSAIDS should be warned of the side effects of gastrointestinal (GI) side effects including gastric bleeding. Patients with renal compromise must be cautioned of renal toxicity. NSAIDS that are selective COX-2 inhibitors may have fewer GI side effects but may have more cardiovascular side effects.

Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids may be used in patients unresponsive to COX-inhibitors or those with posterior or necrotizing disease. A typical starting dose may be 1mg/kg/day of prednisone which should be tapered. Periocular injection of steroids should be avoided as they may enhance collagenase activity and lead to further scleral melting and perforations. Different side effects of steroids that should be taken care include elevated intraocular pressure, decreased resistance to infection, gastric irritation, osteoporosis, weight gain, hyperglycemia, and mood changes.

Immunomodulatory agents

Since it is an autoimmune condition leading to vessel damage (type III hypersensitivity), immunosuppressive therapy, supplemented with steroids is recommended to treat the destructive process. Consultation with a rheumatologist or internal medicine specialist is recommended. Cyclophosphamide is known as the most effective drug in patients with non-infectious necrotizing scleritis (oral dose 2-3 mg/kg/d). Other immunosuppressive drugs like methotrexate (7.5-20 mg weekly), azathioprine (starting dose 2,5 mg/kg/d), cyclosporine (2.5-5.0 mg/kg/d) and mycophenolate mofetil (2-3 g/d)are well described.[5] “Biologics” are the new group of modifying immune response agents. There are some reports describing: tumor necrosis factor inhibitors–TNF1 (etanercept, infliximab), the interleukin-2 receptor blocker (daclizumab), the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra), the antilymphocyte medicament (rituximab, alemtuzumab) in ocular diseases, including scleritis.

Topical Therapy

Frequent lubricant instillation. Topical Sodium Versenate which is an inhibitor of collagenolytic enzyme.[6] For refractory cases topical cyclosporine A is described.

Medical follow up

Adjustment of medications and dosages is based on the level of clinical response. Laboratory testing may be ordered regularly to follow the therapeutic levels of the medication, to monitor for systemic toxicity, or to determine treatment efficacy.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of SP is necessary in cases with exposed uvea to preserve the globe integrity. Tectonic patch grafting can be performed with the sclera (fresh or frozen globe or glycerin preserved scleral tissue), dermis, fascia lata, periosteum, aortic tissue, cartilage, cornea, pedicle-flaps of conjunctiva with Müller muscle or tarsus, synthetic material (GoreTex®) and eventually amniotic membrane.[2]

Complications

Complications include perforation especially after minor trauma and pthisis bulbi, therefore protection from trauma is important.

Prognosis

Gradual reduction of vision is mainly due to progressive astigmatism.

References

- ↑ American Academy of Ophthalmology. Scleromalacia perforans. https://www.aao.org/image/scleromalacia-perforans-3 Accessed July 18, 2019.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kopacz D, Maciejewicz P, Kopacz M Scleromalacia Perforans– What We Know and What We Can Do. J Clinic Experiment Ophthalmol 2013;S2:009.

- ↑ W. A. Manschot . Senile scleral plaques and senile scleromalacia.Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;Jun; 62(6): 376–380.

- ↑ Brad Bowling. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology, A systemic Approach.8th Edition (2016).Chapter 8:Episclera and Sclera. p259.

- ↑ Sakellariou G, Berberidis C, Vounotrypidis P A case of Behcet's disease with scleromalacia perforans. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44: 258-260.

- ↑ Evans PJ, Eustace P Scleromalacia perforans associated with Crohn's disease. Treated with sodium versenate (EDTA). Br J Ophthalmol 1973;57: 330-335.

- Norman Ashton And H. E. Hobbs Effect Of Cortisone On Rheumatoid Nodules Of The Sclera (Scleromalacia Perforans). 1952; Br J. Ophthal.