SHAPU - Seasonal Hyperacute Pan-Uveitis

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Seasonal hyperacute panuveitis (SHAPU) is a mysterious disease seen and reported only from Nepal since 1975. It is an important cause of unilateral childhood blindness and can lead to devastating intraocular inflammatory and loss of sight within a week and, in many cases, disfigurement. Although initially presented as a case report at a Nepal Prevention of Blindness meeting in 1978 and reported in national journals [1], detailed description of the condition including epidemiology, serology, and histology appeared first in an international peer reviewed journal in 1984 as a severe form of pan-uveitis based on several years of work at the Department of Ophthalmology, Institute of Medicine. [2]

Disease

Seasonal Hyperacute Panuveitis (SHAPU) is a unique, rapidly destructive intra-ocular inflammatory disease. It has historically occurred in two year cycles in odd-numbered years since 1975 and has been described to occur between the end of monsoon season (August –September) and the peak of winter (December-January), but recent evidence has shown that it actually occurs every year in either the summer or autumn months[3][1][2].The disease affects children predominantly, is almost always unilateral, and involves rapid deterioration of vision[1][2][4][5][6]. Two thirds of patients present with blindness while the rest lose vision rapidly.

Etiology

Most data on etiology rely solely on contact history with a suspected agent (moths) and there is evidence suggesting that the disease is due to exposure to possible toxins[7]. However, some cases presenting like SHAPU indicate viral or bacterial isolation from eyes with SHAPU, possibly driven by microtrauma from moth hairs and subsequent bacterial infection[3]. In animal experiments using guinea pigs and rabbits as a host, controlled exposure to three species of moths did not reproduce symptoms of SHAPU. Thus, if moths are implicated in the etiology of SHAPU, not all mammals are equally susceptible hosts[3].

SHAPU usually affects one eye, and historically has had a cyclic pattern occurring between the end of monsoon season (August-September) and the beginning of winter (December-January) every odd-numbered year since 1975. However, recent prospective studies have reported cases occurring in the summer months of even-numbered years (2008, 2010)[3]. While this remains unexplained, the most common cause of panuveitis among pediatric patients in Nepal is reported to be SHAPU (27.7%), followed far behind by Toxoplasmosis[8].

Risk Factors

Many retrospective and prospective studies link exposure to various species of moths to acquisition of SHAPU.

In the first comprehensive report of SHAPU, described, a series of animal experiments in which the authors exposed guinea pigs and rabbits to live with Megalopygidae, Arctiidae, and Noctuidae moths in a closed room in four sets of experimental designs described elsewhere. Lesions could not be reproduced in any of the experiments. They concluded that, if moth was indeed either an inducing or transmitting agent, possibly the moths used by them in this experiment were not the type to produce the disease or that the rabbits and guinea pigs were not susceptible hosts and recommended continued vigilance and further studies.

Based on cases seen since the epidemic was first observed and in recent studies, most cases have been reported from subtropical (1,000 to 2,000 meters), temperate (2,000 to 3,000 meters) and subalpine (3,000 to 6,000 meters) regions of eastern, central and western Nepal. Very few cases have been reported from the tropical plains of Nepal.

Geographically, two interesting features requiring further explanation include its localization to certain climatic zones of Nepal while such climatic zones exist in many countries along the Hindukush mountains (Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar and China)[7].

Pathophysiology

Affecting children predominantly, the disease is almost always unilateral with rapid and profound loss of vision.[1][2][4][5][6]Starting as a red-eye with little or no pain, this quickly turns into something more frightening within days. Hypopyon, fibrinous exudates in the anterior chamber, a non-dilating pupil with massive exudation into vitreous start manifesting and eyes then become soft, resulting in "Malignant Hypotony".[2][4]

“White pupillary reflex in red eye" with little or no pain remains the hallmark in most of the cases. No gender predilection is reported in any of the series. No statistically significant difference has been noted regarding laterality among either eye.

Earlier circumstantial evidence of exposure/contact with moths has been subsequently reinforced by clinical observation of intrastromal follicles in the cornea in some cases. However, many further cases failed to demonstrate similar finding. This has caused the origins to be questioned again – making the pathogenesis ever more enigmatic.

Oscillating between non-infective and infective origin, all cases in early reports were treated either with antibiotics, antivirals, immunosuppressive with uniformly poor results[1][4] Early interventional vitrectomy has shown promising outcomes.[6]

Primary Prevention

Currently, the only primary prevention is to avoid contact with moths when in season[7].

Diagnosis

Physical Examination

Seasonality, hyper-acute presentation in otherwise healthy individuals, without history of eye surgery or trauma, white pupil in a red eye, and a shallow anterior chamber in a soft eye without history of previous surgery or eye disease are features not described for any other ocular entity[7].

Clinical Features

Most of the clinical symptoms and signs of SHAPU are non-specific.

Symptoms

- Sudden onset of redness with minimal pain*

- White pupillary reflex (leukocoria) in a red eye *

- Unilateral involvement

- Decreased vision

Signs

- Circumciliary congestion

- Leukocoria

- Fibrinoid anterior chamber reaction

- Hypopyon

- Shallow Anterior chamber

- Collection of fibrinoid exudates in the crypts of muddy iris

- Decreased intraocular pressure (malignant hypotony)*

- Retinal assessment is difficult[7]

Footnote - * Hallmark in most cases

Clinical Diagnosis

Clinical case description and identification of SHAPU

Major

- White pupillary reflex in red eye

- Little or no pain

- Almost always unilateral

- Rapid and profound loss of vision.

Minor

- Malignant Hypotension

- Children predominantly

- Hypopyon, fibrinous exudates in anterior chamber

- A difficult to dilate pupil and inability to visualize retina

SUSPECTED case (1 Major with 1 Minor OR 2 Major criteria)

Major:

- Almost always unilateral

- White pupillary reflex in red eye

Minor:

- Children predominantly

PROBABLE case (Major ≥2 with at least 1 Minor criteria OR 1 Major with 3 Minor criteria)

Major:

- White pupillary reflex in red eye

- Little or no pain

- Almost always unilateral

Minor:

- Children predominantly

- Hypopyon, fibrinous exudates in anterior chamber.

- A difficult to dilate pupil and inability to visualize retina

CONFIRMED Case (Cases matching all the major and minor criteria)

Major:

- White pupillary reflex in red eye

- Little or no pain

- Almost always unilateral

- Rapid and profound loss of vision

Minor:

- Malignant Hypotension

- Children predominantly

- Hypopyon, fibrinous exudates in anterior chamber.

- A difficult to dilate pupil and inability to visualize retina

Diagnostic procedures

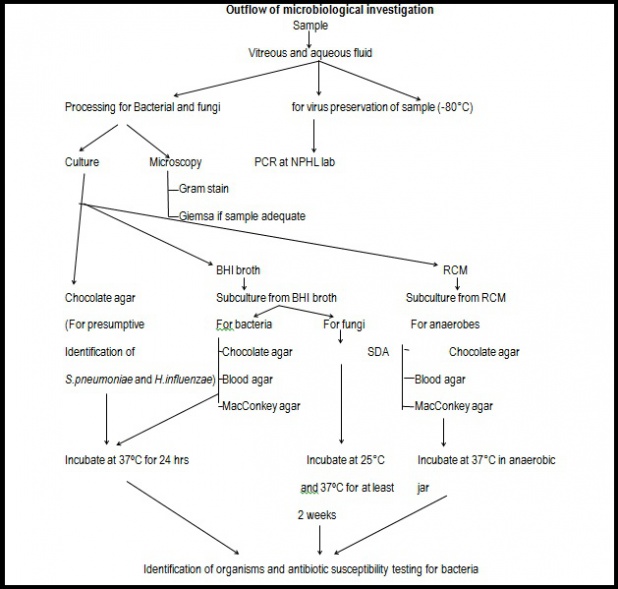

Laboratory test

Specimen collection

- Specimens-vitreous fluid, aqueous fluid, conjunctival swab, blood

- Specimens should be collected by ophthalmologists in the operation theater maintaining the sterility.

- Both diluted and undiluted vitreous fluid should be collected in a sterile syringe.

- The conjunctival swab should also be collected from both eyes. It serves as a control when comparing with the ocular fluid samples

- Blood sample is collected to rule out endogenous endophthalmitis

Specimen transportation

- Specimens are inoculated in the culture medium - mainly for bacterial and fungal isolation. The inoculated media and slides prepared should be immediately transported to the laboratory.

- OR the samples are directly transported to the laboratory for culture and staining.

- Some amount of sample should be preserved for viral PCR and future use at -80°C.

Procedure

- Each of the samples (except the blood) should be inoculated in brain heart infusion broth, Chocolate agar and Robertson’s cooked meat media for bacterial culture and fungal culture. Incubation should be done at 37°C for at least 24-48 hours.

- Chocolate agar is for the identification of Haemophilus influenza and Streptococcus pneumonia.

- Subculture from brain heart infusion broth should be done in Chocolate agar, Blood agar and MacConkey agar and incubated at 37°C for 24-48 hours for isolation of other aerobic bacteria.

- Subculture from brain heart infusion broth should be done in Sabouraud’s dextrose agar and incubated at 25°C and 37°C over a period of 3 weeks for fungal culture.

- Robertson’s cooked meat media is for anaerobic culture. Subculture should be done in Chocolate agar, Blood agar and MacConkey agar and incubated at 37°C for 48-72 hours in an anaerobic jar.

- 2-3 smears should be prepared from each sample (except the blood) for gram staining and Giemsa staining.

- Blood sample should be inoculated into Brain heart infusion broth and incubated at 37°C. Subculture should be done in Chocolate agar, Blood agar, MacConkey agar after 24 hours and/or after appearance of turbidity.

- Viral PCR should be done and sequencing of the preserved sample should be done.

Identification

Identification of the bacteria and fungi should be done based on their morphology and various biochemical tests.

Interpretation (for bacterial and fungal growth)

Vitreous fluid

Any growth is significant if growth is present in both diluted and undiluted sample.

Note – growth for any sample is considered significant if same organism grows in 2 solid or 1 liquid and 1 solid medium.

Aqueous fluid

Any growth is significant if is present in aqueous fluid but the organism grown in aqueous fluid should be same as that grown in vitreous for it to be the causative agent of SHAPU.

If growth is present in aqueous fluid but not in vitreous, that may be other pathology of eye.

Conjunctival swab

If growth of the organism in the conjunctival swab of the affected eye is same as that of the normal eye, it indicates that the organism is a normal flora. But if organism grown in conjunctival swab culture and vitreous fluid is the same, the flora itself is the pathogen. For the confirmation, a repeat conjunctival swab and vitreous tap should be done (if possible) to rule out contamination during the procedure

Blood culture

Growth of same organism in blood and vitreous fluid culture indicates that the cause of panuveitis is endogenous or it is a condition of secondary bacteremia.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis therefore may include a range of entities.

Infectious conditions

- Endogenous endophthalmitis

- Exogenous endophthalmitis

- Herpetic retinitis

- Tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Fungal infection in drug users

- HIV retinopathy

- Toxoplasmosis

Immunological conditions

- Sarcoidosis

- Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome (MEWDS)

- Behcet’s disease

Management

The patients will mostly be received as emergency cases or OPD cases. Doctors should perform a thorough history and detailed ocular evaluation. Systemic examinations will also be performed to rule out any systemic associations.

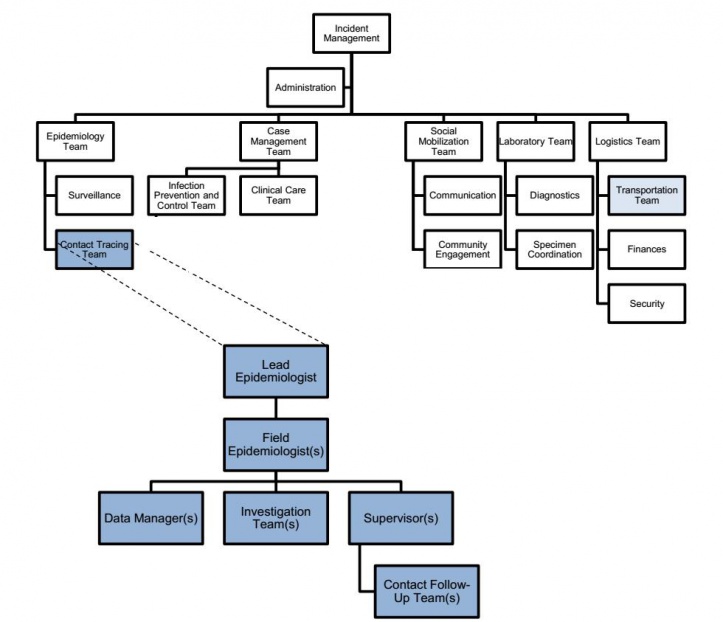

Upadhyay et al also recommends the following hierarchy system to be established for better management of the cases[7].

History should be taken in details and following points should be included in it:

- Patients profile including age, sex, and address (Temporary and permanent)

- Ocular Complaint

- Contact/Exposure history

Definition of Contact/ Exposure History:

Any person who has been exposed to or has had direct physical contact with:

- Live or dead moth immediately prior to onset of the condition.

- Hair/follicles at work/home – e.g.: de-dusting, gardening, farming

As well as:

- Past ocular medical and surgical history

- Systemic illness/medication

- Family and personal history

- Treatment history

After taking a detailed history, the ocular examination should be done systemically as stated below:

Non-Invasive Evaluation:

- Visual Acuity

- Extraocular movements

- Periorbital region/lids and adnexal examination using slit lamp

- Special mentions about Conjunctiva, episclera, and sclera if any.

- Anterior segment examination of the cornea

- Anterior chamber, iris, pupil, and lens. Pupillary light reflex both direct and consensual should be noted using bright torchlight. Clinical photography is mandatory for documentation

- Proparacaine Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution USP, 0.5% should be instilled in both eyes and after 30 seconds, the Intraocular pressure should be taken with the help of Goldmann applanation tonometer if patient permits.

- Detailed fundus examination under mydriasis using eye drop Tropicamide 1% should be performed with direct ophthalmoscope, binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy with +20D lens and h +90D lens whenever indicated and feasible. In cases with a poor fundal view, ocular ultrasonography should be done and the findings documented.

- In cases with some fundal view, OCT can be used as a noninvasive method for microscopic anatomical evaluation.

Medical therapy

For any suspicious case of SHAPU, topical antibiotics can be started in affected eye and case should be referred promptly[7].

Moxifloxacin once hourly, Prednisolone acetate once hourly, Atropine TDS, Ceftriaxone intravenous 50 to 75 mg/kg IV or IM once a day or adults 1-2 g IV or IM OD or BD, Methylprednisolone intravenous ( <20 kg=500mg OD, 20-40kg=125mg QID or 250mg BD, > 40kg=250mg QID or 500mg BD)for up to 3 days and followed by oral steroids (1-2mg per kg body weight) for up to 4-6 weeks depending on clinical condition.

Surgery

All cases should undergo core vitrectomy with diagnostic vitreous tap within 24 hours of presentation[7][9].

After completing of core vitrectomy, intravitreal antibiotics should be given as following:

- Vancomycin 1.0 mg, Amikacin 400 microgram and Dexamethasone 400 microgram.

- Repeat intravitreal after 48 hours if no improvements with vitreous tap again, if previous sample showed failed to demonstrate any organism or its growth.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Malla O, editor Endophthalmitis probably caused by Tussock moth. Report of the Proceedings of the first National Seminar on Prevention of Blindness; 1978.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Upadhyay, MP: Eye problems of Nepalese Children (1979). In Baral, M.R. (Ed.) The child in Nepal Nepal Medical Association/International year of the Child (IYC) Seminar.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Manandhar A. Seasonal hyperacute panuveitis. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2011;22(6):496-501. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e32834bcbf4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Upadhyay MP. Anterior Segment Blindness among Nepalese Children. Nepas. J. 2:69)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Upadhayay M, Rai N, Ogg J. Seasonal Hyper Acute Panuveitis in Saarikm (ed): Uveitis update. Amsterdam. Excerpta Medica. 1984.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Upadhyay M, Rai N, Ogg J, SHRESTHA B. Seasonal hyperacute panuveitis. Uveitis update. 1984:257-62.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Upadhyay M, Sitaula RK, Shrestha B, et al. Seasonal Hyperacute Panuveitis in Nepal: A Review over 40 Years of Surveillance. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2018;27(5):709-717. doi:10.1080/09273948.2018.1439643.

- ↑ Manandhar A. Seasonal hyperacute panuveitis: an update. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2011;22(6):496-501.

- ↑ Byanju R, Pradhan E, Rai S, Sapkota Y. Visual outcome of vitrectomy in seasonal hyperacute pan uveitis. 2003.

- ↑ Shrestha E. A profile and treatment outcome of seasonal hyper-acute panuveitis. Nepalese Journal of Ophthalmology. 2010;2(1):35-8.