Raeder Syndrome

All content on Eyewiki is protected by copyright law and the Terms of Service. This content may not be reproduced, copied, or put into any artificial intelligence program, including large language and generative AI models, without permission from the Academy.

Disease Entity

Disease

Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome (RPS), also known as Raeder syndrome or paratrigeminal neuralgia, is an uncommon neurological disorder characterized by unilateral oculosympathetic paralysis (i.e., Horner syndrome) accompanied by ipsilateral sensory and/or motor abnormalities in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve fibers. It is often described as a painful, postganglionic, incomplete Horner syndrome. The first patient described by Dr Raeder in 1918 demonstrated left sided eye and head pain, ptosis, and miosis, without anhidrosis. It can also include additional cranial nerve (CN) deficits. RPS is a diagnosis of exclusion and neuroimaging is recommended because middle cranial fossa or cavernous sinus lesions (V1 pain and Horner syndrome) or ipsilateral carotid artery dissection with referred V1 pain can mimic RPS.[1][2]

History & Subtypes

In 1924, Norwegian ophthalmologist Johan Georg Raeder reported 5 patients experiencing unilateral oculosympathetic paresis (i.e., Horner syndrome)and ipsilateral trigeminal involvement (e.g., neuralgic pain, decreased facial sensation, trigeminal muscle weakness, etc.). In 4 of 5 of these cases, there was no sweating defect and no involvement of other cranial nerves (e.g., diplopia).[3] He had localized lesions in the middle fossa, through which the trigeminal and sympathetic nerve fibers innervating the eye run through. Hence naming the syndrome “paratrigeminal” neuralgia.

Several subsequent reports of non-neuralgic head pain and ipsilateral oculosympathetic paralysis with no other CN involvement[4][5] [6][7][8] have also been labeled as Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome. This description was consistent with only one of the five patients Raeder initially described, which has led to debate about the true definition.[9] Since the initial description, there has been further categorization of the disorder.

In 1962, Boniuk and Shelzinger provided their own classification of Raeder syndrome into two types: group I and group II. The group I variant included patients who experienced additional parasellar nerve involvement (e.g., CN III, IV, VI) in addition to the oculosympathetic paresis and trigeminal nerve involvement. The group II subtype occurs without parasellar involvement. They concluded group II Raeder syndrome was a “benign” entity with a favorable outcome and a self-limited course, although miosis and ptosis may remain.[6] In the modern neuroimaging era however RPS of either type should generally be considered a diagnosis of exclusion and should meet International Headache Society (IHS) criteria (see below).

Grimson and Thompson modified Boniuk’s classification and introduced 3 RPS subdivisions.[10] Group I was identical to Boniuk’s, detailed above. They delineated group II as patients with cluster headache and an isolated oculosympathetic paresis, and group III as a painful postganglionic Horner syndrome with involvement of only the 1st division of the trigeminal nerve.

Table 1. Groups of Raeder Syndrome as defined by Boniuk and Shelzinger (1962) and Grimson and Thompson (1980).

| Boniuk and Shelzinger (1962) | Grimson and Thompson (1980) | |

|---|---|---|

| Group I | Oculosympathetic paresis + Trigeminal nerve

involvement + Parasellar nerve involvement (CN III, IV, VI) |

Oculosympathetic paresis + Trigeminal nerve

involvement + Parasellar nerve involvement (CN III, IV, VI) |

| Group II | Oculosympathetic paresis + Trigeminal nerve

involvement + No parasellar nerve involvement |

Cluster headache + isolated oculosympathetic

paresis |

| Group III | ---- | Postganglonic Horner + Involvement of first

division of trigeminal nerve |

Mokri argued Raeder Syndrome should only be attributed to cases that were characteristically described as Group I. He also emphasized the need for true trigeminal involvement rather than mere head/face pain to make a diagnosis, claiming many of the subsequent case reports were more simply vascular headaches (e.g., migraine headaches).[9]

Pathogenesis

The most common definition of the Raeder syndrome is a painful third-order neuron Horner syndrome that involves the sympathetic fibers that ultimately innervate Müller (Figure 1) muscle of the superior eyelid, the inferior sympathetic lid retractor, and the dilator muscles of the iris. These third-order sympathetic neurons arise from the superior cervical ganglion and enter the cranial vault with the internal carotid artery (ICA) into the cavernous sinus. Here the oculosympathetic fibers leave the ICA, travel for a short time with CN VI, and then join the 1st division of the trigeminal nerve to enter the orbit through the superior orbital fissure. Given this anatomy, the various forms of Raeder syndrome have been proposed to involve the the oculosympathetic pathway, trigeminal nerve, and variable involvement of other cranial nerves (CN III, IV, VI), localizing the lesion to the middle cranial fossa. The sympathetic fibers involved in facial sweating diverge from the main branches and follow the external carotid artery after the carotid artery bifurcation. Therefore, the preservation of facial sweating in Raeder syndrome localizes the lesion distal to the bifurcation.

The trigeminal fibers from the ophthalmic division V1 and parasympathetic fibers of the CN III may not affected, therefore, pain occurs without sensory or parasympathetic dysfunction. It is hypothesized that the pain sensed in the inferior deep portion of the orbit and nasal fossa might be explained by the synapses between the pterygopalatine ganglion and the lateral sellar plexus.[11] Additionally, the periorbital pain occurring in an ipsilateral carotid dissection is hypothesized to originate from general visceral afferent fibers (referred pain).

Etiology

Many reports are idiopathic. However, a variety of underlying pathologies have been reported:[10]

- ICA Abnormalities (e.g, aneurysm, dissection, occlusion, inflammation, congenital abnormalities, fibromuscular dysplasia, trauma)[12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

- Neoplasms of the middle cranial fossa and cavernous sinus (e.g., involving the Gasserian ganglion, local invasion, metastasis, lymphoma)[3][19][20]

- Inflammation (e.g., dental abscess, chronic sinusitis, etc.)[21][22][23]

- Trauma (e.g., basilar skull fracture, iatrogenic injury to Gasserian ganglion, gunshot wound)[3]

- Iatrogenic, occurring after embolization of a giant intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm. In a case report by Esteves, et. al, the authors hypothesized that sympathetic nerves located around the internal carotid artery were compressed against the bony wall of the carotid canal when the balloon was placed. This ultimately led to sympathetic dysfunction, as well as activation of pain receptors in the trigemino-vascular system, which would account for the ipsilateral periorbital pain.[11]

Oculosympathetic paralysis with hemicranial pain has been recognized as a clinical manifestation of a spontaneous ICA dissection.[14][15][24][2] It is an important diagnosis to recognize early because of the potential for acute ischemic neurologic sequela.

Raeder syndrome has also been associated to cluster headache[9], SUNCT syndrome, herpes zoster ophthalmicus[6], Hemicrania continua[25], Tolosa-Hunt syndrome[26], vasculitis[12], hypertension[12], head trauma[12], migraine headaches[4][6][8][12][13][11] and Lyme disease[27]

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of idiopathic Raeder syndrome is unknown, but it is an uncommon disorder[12] This disorder most commonly affects middle-aged men.

Diagnosis

Signs & Symptoms

Patients classically present with unilateral headache with or without facial pain or sensory deficits associated with an ipsilateral ptosis and miosis. The head/facial pain is located in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve which can often be periocular or retroorbital. It may be limited to the ophthalmic division of CN V, but it can also involve the cheek and teeth (maxillary division). The pain can be severe and lancinating, often radiating to the face (i.e., tic douloureux-like neuralgia). It may last from hours to weeks to months, and typically remains constant. Pain may occasionally follow a recurrent pattern of “attacks,” similar to cluster headaches.[9][10]

The trigeminal nerve involvement can also include other sensory or motor abnormalities including decreased sensation of the face, decreased corneal reflex, allodynia, and muscle weakness (e.g., pterygoid and masseter muscles). Patients may complain of symptoms indicating additional cranial nerve involvement such as diplopia and decreased hearing. Other signs and symptoms that may be seen include conjunctival hyperemia, excessive tearing, apparent enophthalmos, and decreased IOP.[6][9]

Physical Examination

Examination may demonstrate anisocoria that is more pronounced in the dark (with dilation lag), due to impairment of the oculosympathetic pathway. Mild ptosis and upside down ptosis of the ipsilateral eye may be present due to the involvement of the sympathetic innervation to Müller’s and Horner’s muscles. Palpation of the head and face may reveal sensory deficits. Careful neurological exam, including extraocular movements, corneal reflex, and facial sensation could be considered in order to undercover any other cranial nerve involvement.

Diagnostic criteria

The International Headache Society criteria for the diagnosis of Raeder Syndrome include[1]:

- Constant, unilateral headache fulfilling criterion C.

- Imaging evidence of underlying disease of either the middle cranial fossa or of the ipsilateral carotid artery

- Evidence of causation demonstrated by both of the following:

- Headache has developed in temporal relation to the onset of the underlying disorder

- Headache has either or both of the following features:

- Localized to the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, with or with-out spread to the maxillary division

- Aggravated by eye movement

- Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.”

Paratrigeminal neuralgia, similar to painful Horner syndromes, is a clinical diagnosis and requires neuroimaging. However, pharmacologic testing can help to confirm the diagnosis.

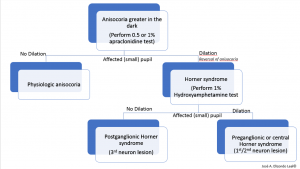

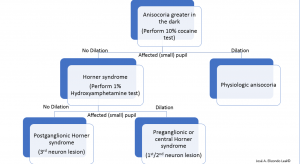

Pharmacologic Testing

Either 1% or 0.5% apraclonidine, an alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist may be used. Under normal circumstances, the alpha-2 agonist effect in the pre-synaptic membrane will predominate. In contrast, if oculosympathetic denervation is present, there will be a supersensitivity that will allow the post-synaptic alpha-1 agonist action to predominate, leading to pupillary dilation of the affected eye with mild constriction of the normal pupil; this can produce a relative reversal of anisocoria and confirms a Horner syndrome pharmacologically. Alternative topical diagnostic tests for Horner syndrome include cocaine and hydroxyamphetamine (Figure 2).

Cocaine inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine allowing accumulation of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft, perpetuating a sympathetic adrenergic response. Thus, 10% topical cocaine will produce dilation in the normal eye but fail to produce the same degree of dilation in the affected eye. A drop of topical cocaine should be placed in both eyes, and checked after 15 minutes. If no change in pupillary size is noted, the drop test should be repeated, and pupils rechecked in another 15 minutes.[28][24] A lack of pupillary dilation of the abnormal pupil suggests oculosympathetic denervation but does not further localize the lesion.

Hydroxyamphetamine may be used next to differentiate between a first- or second-neuron versus a third-order neuron lesion. Topical 1% hydroxyamphetamine may therefore distinguish between pre- and post- ganglionic lesions in the oculosympathetic pathway.[28]Hydroxyamphetamine leads to release of norepinephrine from the third-order neuron junction with the iris. Therefore, in the case of third-order neuron disorder, such as paratrigeminal neuralgia, the pupil of the affected eye would fail to dilate as well as the fellow, control, normal pupil. Equal dilation of the pupils after hydroxyamphetamine testing (in a cocaine or apraclonidine confirmed Horner syndrome) would be suggestive of a first or second-order neuron disorder (Figure 3 and 4). Many authors have recommended abandoning pharmacologic testing and proceeding with neuroimaging of the entire oculosympathetic axis in patients with clinically diagnosed Horner syndrome due to the variable sensitivity and specificity of the topical pharmacologic testing.

Imaging

In general, patients with RPS should undergo neuroimaging (typically MRI/MRA or CT/CTA of the head and neck to T2 level) to exclude compressive or vascular (e.g., internal carotid artery dissection) lesions as described above. [29][30]

Management

Treatment

The treatment of Raeder syndrome depends entirely on the underlying etiology.

Dissection of the ICA should prompt urgent management to prevent embolic events or progression of the dissection. Initiation of anticoagulation (uncommon) and antiplatelet therapy (common) should be considered. Rarely surgical intervention is needed if ischemia is refractory to treatment or if high risk characteristics of the ICA dissection are present.[31]

Without any intracranial etiology, treatment is largely aimed for symptomatic relief. NSAIDs, aspirin, and codeine compounds have been reported to be helpful in controlling the pain of head and face. Ergotamine[9], steroids[25], and intensive vitamin-B therapy have been administered with success in helping alleviate pain.[9][32] There have been some reports of patients noting increased severity of pain after ingestion of alcoholic beverages. Therefore, it is recommended that patients avoid triggers (e.g., vasodilating agents, particularly alcohol) during the active stage of the disease.[6]

Follow-Up

Follow up of Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome depends on the underlying etiology.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the underlying etiology. However, in the absence of other parasellar nerve involvement (group II) the prognosis is quite excellent with resolution of symptoms typically weeks to months from onset. Koutsis et al. described a 50-year-old man with Raeder paratrigeminal syndrome that evolved into a hemicrania continua type of headache 10 months after onset which responded well to indomethacin.[33]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). Cephalalgia. 2013 Jul;33(9):629-808.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Kline LB, Vitek JJ, Raymon BC. Painful Horner's syndrome due to spontaneous carotid artery dissection. Ophthalmol. 1987;94:226-230.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 Raeder JG. Paratrigeminal paralysis of the oculopupillary sympathetics. Brain. 1924; 47:149-58.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 Smith JL. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;46:194-201.

- ↑ Ford FR, Walsh FB. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome: a benign disorder, possibly a complication of migraine. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1958;103:296-298.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Bonuik M, Schlezinger NS. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1962;54:1074-1084.

- ↑ Klingon GH, Smith WM. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Neurology. 1956;6:750-753.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Minton LR, Bounds GW,Jr. Raeder's Paratrigeminal Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1964;58:271-275.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Mokri B. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Original concept and subsequent deviations. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:395-399.

- ↑ Jump up to: 10.0 10.1 10.2 Grimson BS, Thompson HS. Raeder's syndrome. A clinical review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24:199-210.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tatsui CE, Prevedello DM-S, Koerbel A, Cordeiro JG, Ditzel LFDS, Araujo JC. Raeders syndrome after embolization of a giant intracavernous carotid artery aneurysm: pathophysiological considerations. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63(3a):676-680. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2005000400024.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Murnane M, Proano L. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome: a case report. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:864-867.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 Jain DC, Ahuja GK, Goulatia RK. Intracranial internal carotid artery aneurysm as a cause of Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Surg Neurol. 1981;16:357-359.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Cohen DN, Zakov ZN, Salanga VD, Dohn DF. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:1044-1049.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 Selky AK, Pascuzzi R. Raeder's paratrigeminal syndrome due to spontaneous dissection of the cervical and petrous internal carotid artery. Headache. 1995;35:432-434.

- ↑ Kashihara K, Ito H, Yamamoto S, Yamano K. Raeder's syndrome associated with intracranial internal carotid artery aneurysm. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:49-51.

- ↑ Healy JF, Zyroff J, Rosenkrantz H. Raeder syndrome associated with lesions of the internal carotid artery. Radiology. 1981;141:101-104.

- ↑ Moris G, Ribacoba R, Solar DN, and Vidal JA. Dolichoectasia of the cavernous internal carotid artery: another cause for Raeder’s syndrome. J Headache Pain 2000;2:123-5.

- ↑ Harrington HJ, Mayman CI. Carotid body tumor associated with partial Horner's syndrome and facial pain ('Raeder's syndrome'). Arch Neurol. 1983;40:564-566.

- ↑ Nogaki H, Nakamura M, Tatsumi S. A case of Raeder's syndrome caused by metastatic malignant lymphoma. No To Shinkei. 1989;41:259-262.

- ↑ Bedrossian EH. Raeder's syndrome. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1952;48:620-623.

- ↑ Nolph MB, Dion MW. Raeder's syndrome associated with internal carotid artery dilation and sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1144-1148.

- ↑ Nagel MA, Bert RJ, Gilden D. Raeder syndrome produced by extension of chronic inflammation to the internal carotid artery. Neurology. 2012;79(12):1296-1297. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e31826aad1f.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 Mokri B, Sundt TM,Jr, Houser OW, Piepgras DG. Spontaneous dissection of the cervical internal carotid artery. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:126-138.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 Porzukowiak TP. Raeder Paratrigeminal Neuralgia Evolving to Hemicrania Continua. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:S81YS87

- ↑ 34 Hoes MJAJM, Bruyn GW, Vielvoye GJ. The Tolosa-Hunt syndrome-literature review: seven new cases and a hypothesis. Cephalalgia, 1981 12 01: Vol. 1, pp. 181-94. Oslo. ISSN 0333-1024.

- ↑ Murphy MA, Szabados EM, Mitty JA. Lyme disease associated with postganglionic Horner syndrome and Raeder paratrigeminal neuralgia. J Neuroophthalmol. 2007;27:123-124.

- ↑ Jump up to: 28.0 28.1 Bagheri N, Wajda BN, et al. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. 7. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

- ↑ Castillo M, Kramer L. Raeder syndrome: MR appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:1121-1123.

- ↑ Auer D, Karnath HO, Nagele T, Dichgans J. Noninvasive investigation of pericarotid syndrome: role of MR angiography in the diagnosis of internal carotid dissection. Headache. 1995;35:163-168.

- ↑ Kadkhodayan Y , Jeck DT, Moran CJ, et al., Angioplasty and Stenting in Carotid Dissection with or without Associated Pseudoaneurysm. AJNR. October 2005, 26 (9) 2328-2335.

- ↑ Nolph MB, Dion MW. Raeder's syndrome associated with internal carotid artery dilation and sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1982 Oct. 92(10 Pt 1):1144-8.

- ↑ Koutsis G, Andreadou E, Matsi S, Evangelopoulos ME, Sfagos C. Benign Raeder Syndrome Evolving Into Indomethacin‐Responsive Hemicranial Headache. J Headache Pain. 2008;48:1534-1536.

- Thomas JE, Yoss RE. The parasellar syndrome: problems in determining etiology. Mayo Clin Proc. 1970;45:617-623.

- Godtfredsen E, Lederman M. Diagnostic and Prognostic Roles of Ophthalmoneurologic Signs and Symptoms in Malignant Nasopharyngeal Tumors. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965;59:1063-1069.